Chapter 615 Disorders of Eye Movement and Alignment

Strabismus

Clinical Manifestations and Treatment

Comitant Strabismus

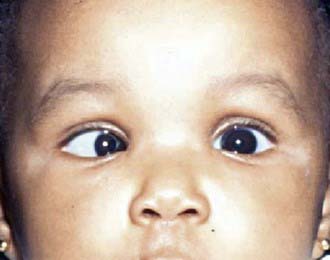

The characteristic angle of congenital esodeviations is large and constant (Fig. 615-1). Because of the large deviation, cross-fixation is often encountered. This is a condition in which the child looks to the right with the left eye and to the left with the right eye. With cross-fixation, there is no need for the eye to turn away from the nose (abduction) because the adducting eye is used in side gaze; this condition simulates a 6th nerve palsy. Abduction can be demonstrated by the doll’s head maneuver or by patching 1 eye for a short time. Children with congenital esotropia tend to have refractive errors similar to those of normal children of the same age. This contrasts with the characteristic high level of farsightedness associated with accommodative esotropia. Amblyopia is common in children with congenital esotropia.

The primary goal of treatment in congenital esotropia is to eliminate or reduce the deviation as much as possible. Ideally, this results in normal sight in each eye, in straight-looking eyes, and in the development of binocular vision. Early treatment is more likely to lead to the development of binocular vision, which helps to maintain long-term ocular alignment. Once any associated amblyopia is treated, surgery is performed to align the eyes. Even with successful surgical alignment, it is common for vertical deviations to develop in children with a history of congenital esotropia. The two most common forms of vertical deviations to develop are inferior oblique muscle overaction and dissociated vertical deviation. In inferior oblique muscle overaction, the overactive inferior oblique muscle produces an upshoot of the eye closest to the nose when the patient looks to the side (Fig. 615-2). In dissociated vertical deviation, 1 eye drifts up slowly, with no movement of the other eye. Surgery may be necessary to treat either or both of these conditions.

To treat accommodative esotropia, the full hyperopic (farsighted) correction is initially prescribed. These glasses eliminate a child’s need to accommodate and therefore correct the esotropia (Fig. 615-3). Although many parents are initially concerned that their child will not want to wear glasses, the benefits of binocular vision and the decrease in the focusing effort required to see clearly provide a strong stimulus to wear glasses, and they are generally accepted well. The full hyperopic correction sometimes straightens the eye position at distance fixation but leaves a residual deviation at near fixation; this may be observed or treated with bifocal lenses, antiaccommodative drops, or surgery.

Third Nerve Palsy

A 3rd nerve palsy, whether congenital or acquired, usually results in an exotropia and a hypotropia, or downward deviation of the affected eye, as well as complete or partial ptosis of the upper lid (Fig. 615-4). This characteristic strabismus results from the action of the normal, unopposed muscles, the lateral rectus muscle, and the superior oblique muscle. If the internal branch of the 3rd nerve is involved, pupillary dilation may be noted as well. Eye movements are usually limited nasally in elevation and in depression. In addition, clinical findings and treatment may be complicated in congenital and traumatic cases of 3rd nerve palsy owing to misdirection of regenerating nerve fibers, referred to as aberrant regeneration. This results in anomalous and paradoxical eyelid, eye, and pupil movement such as elevation of the eyelid, constriction of the pupil, or depression of the globe on attempted medial gaze.

Sixth Nerve Palsy

Congenital 6th nerve palsies are rare. Decreased lateral gaze in infants is often associated with other disorders, such as congenital esotropia or Duane retraction syndrome (Chapter 585.9). In neonates, a transient 6th nerve paresis can occur; it usually clears spontaneously by 6 wk. It is thought that increased intracranial pressure associated with labor and delivery is the contributing factor.

Strabismus Syndromes

Monocular Elevation Deficiency

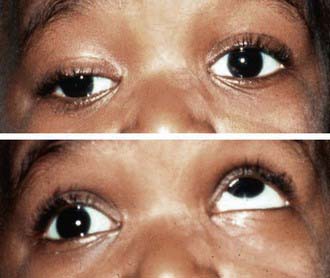

A monocular elevation deficiency is an inability to elevate the eye in both adduction and abduction. It can represent a paresis of both elevators, the superior rectus and inferior oblique muscles, or a possible restriction to elevation from a fibrotic inferior rectus muscle. When an affected child fixates with the nonparetic eye, the paretic eye is hypotropic and the ipsilateral upper eyelid can appear ptotic. Fixation with the paretic eye causes a hypertropia of the nonparetic eye and a disappearance of the ptosis (Fig. 615-5). Because the apparent ptosis is actually secondary to the strabismus, correction of the hypotropia treats the pseudoptosis.

Duane Syndrome

Duane syndrome (Chapter 585.9) is a congenital disorder of ocular motility characterized by retraction of the globe on adduction. This is attributed to the absence of the 6th nerve nucleus and anomalous innervation of the lateral rectus muscle, which results in co-contraction of the medial and lateral rectus muscles on attempted adduction of the affected eye. Within the spectrum of Duane syndrome, patients can exhibit impairment of abduction, impairment of adduction, or upshoot or downshoot of the involved eye on adduction. They can have esotropia, exotropia, or relatively straight eyes. Many exhibit a compensatory head posture to maintain single vision. Some develop amblyopia. Surgery to improve alignment or to reduce a noticeable face turn can be helpful in selected cases.

Möbius Syndrome

The distinctive features of Möbius syndrome (Chapter 585.9) are congenital facial paresis and abduction weakness. The facial palsy is commonly bilateral, often asymmetric, and often incomplete, tending to spare the lower face and platysma. Ectropion, epiphora, and exposure keratopathy can develop. The abduction defect may be unilateral or bilateral. Esotropia is common. The cause is unknown. Whether the primary defect is maldevelopment of cranial nerve nuclei, hypoplasia of the muscles, or a combination of central and peripheral factors is unclear. Some familial cases have been reported. Associated developmental defects include ptosis, palatal and lingual palsy, hearing loss, pectoral and lingual muscle defects, micrognathia, syndactyly, supernumerary digits, and the absence of hands, feet, fingers, or toes. Surgical correction of the esotropia is indicated, and any attendant amblyopia should be treated.

Brown Syndrome

In Brown syndrome, elevation of the eye in the adducted position is restricted (Fig. 615-6). An associated downward deviation of the affected eye in adduction can also occur. A compensatory head posture may be evident.

Congenital Ocular Motor Apraxia

Congenital ocular motor apraxia is a congenital disorder of conjugate gaze characterized by a defect in voluntary horizontal gaze, compensatory jerking movement of the head, and retention of slow pursuit and reflexive eye movements (Chapter 590.1). Additional features are absence of the fast (refixation) phase of optokinetic nystagmus and obligate contraversive deviation of the eyes on rotation of the body. Affected children typically are unable to look quickly to either side voluntarily in response to a command or in response to an eccentrically presented object but may be able to follow a slowly moving target to either side. To compensate for the defect in purposive lateral eye movements, children jerk their head to bring the eyes into the desired position and might also blink repetitively in an attempt to change fixation. The signs tend to become less conspicuous with age.

Nystagmus

Nystagmus (rhythmic oscillations of one or both eyes) may be caused by an abnormality in any one of the three basic mechanisms that regulate position and movement of the eyes: the fixation, conjugate gaze, or vestibular mechanisms. In addition, physiologic nystagmus may be elicited by appropriate stimuli (Table 615-1 and Chapter 590.1).

| PATTERN | DESCRIPTION | ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Latent nystagmus | Conjugate jerk nystagmus toward viewing eye | Congenital vision defects, occurs with occlusion of eye |

| Manifest latent nystagmus | Fast jerk to viewing eye | Strabismus, congenital idiopathic nystagmus |

| Periodic alternating | Cycles of horizontal or horizontal-rotary that change direction | Caused by both visual and neurologic conditions |

| See-saw nystagmus | One eye rises and intorts as the other eye falls and extorts | Usually associated with optic chiasm defects |

| Nystagmus retractorius | Eyes jerk back into orbit or toward each other | Caused by pressure on mesencephalic tegmentum (Parinaud syndrome) |

| Gaze-evoked nystagmus | Jerk nystagmus in direction of gaze | Caused by medications, brainstem lesion, or labyrinthine dysfunction |

| Gaze-paretic nystagmus | Eyes jerk back to maintain eccentric gaze | Cerebellar disease |

| Downbeat nystagmus | Fast phase beating downward | Posterior fossa disease, drugs |

| Upbeat nystagmus | Fast phase beating upward | Brainstem and cerebellar disease; some visual conditions |

| Vestibular nystagmus | Horizontal-torsional or horizontal jerks | Vestibular system dysfunction |

| Asymmetric or monocular nystagmus | Pendular vertical nystagmus | Disease of retina and visual pathways |

| Spasmus nutans | Fine, rapid, pendular nystagmus | Torticollis, head nodding; idiopathic or gliomas of visual pathways |

From Kliegman R: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders.

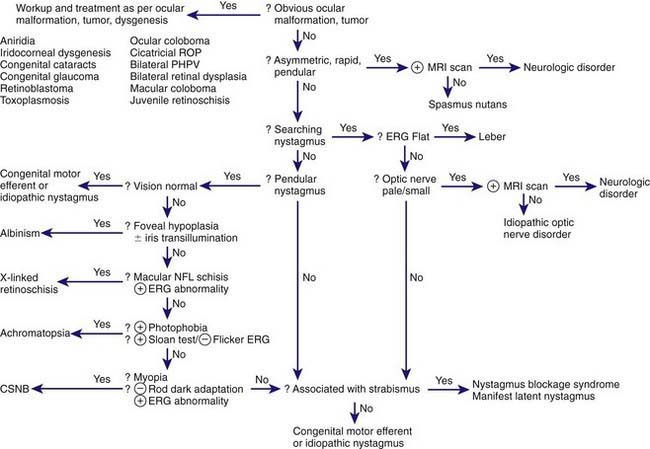

A diagnostic approach to nystagmus is noted in Figure 615-7.

Spasmus nutans is a special type of acquired nystagmus in childhood (Table 590-6). In its complete form, it is characterized by the triad of pendular nystagmus, head nodding, and torticollis. The nystagmus is characteristically very fine, very rapid, horizontal, and pendular; it is often asymmetric, sometimes unilateral. Signs usually develop within the 1st yr or 2 of life. Components of the triad can develop at various times. In many cases, the condition is benign and self-limited, usually lasting a few months, sometimes years. The cause of this classic type of spasmus nutans, which usually resolves spontaneously, is unknown. Some children exhibiting signs resembling those of spasmus nutans have underlying brain tumors, particularly hypothalamic and chiasmal optic gliomas. Appropriate neurologic and neuroradiologic evaluation and careful monitoring of infants and children with nystagmus are therefore recommended.

Other Abnormal Eye Movements

To be differentiated from true nystagmus are certain special types of abnormal eye movements, particularly opsoclonus, ocular dysmetria, and flutter (Table 615-2 and Chapter 590.1).

Table 615-2 SPECIFIC PATTERNS OF NON-NYSTAGMUS EYE MOVEMENTS

| PATTERN | DESCRIPTION | ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Opsoclonus | Multidirectional conjugate movements of varying rate and amplitude | Hydrocephalus, diseases of brainstem and cerebellum, neuroblastoma |

| Ocular dysmetria | Overshoot of eyes on rapid fixation | Cerebellar dysfunction |

| Ocular flutter | Horizontal oscillations with forward gaze and sometimes with blinking | Cerebellar disease, hydrocephalus, or central nervous system neoplasm |

| Ocular bobbing | Downward jerk from primary gaze, remain for a few seconds, then drift back | Pontine disease |

| Ocular myoclonus | Rhythmic to-and-fro pendular oscillations of the eyes, with synchronous nonocular muscle movement | Damage to red nucleus, inferior olivary nucleus, and ipsilateral dentate nucleus |

From Kliegman R: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders.

Opsoclonus

Opsoclonus and ataxic conjugate movements are spontaneous, nonrhythmic, multidirectional, chaotic movements of the eyes. The eyes appear to be in agitation, with bursts of conjugate movement of varying amplitude in varying directions. Opsoclonus is most often associated with encephalitis. It may be the first sign of neuroblastoma (Chapter 492).

Buck D, Powell C, Cumberland P, et alImproving Outcomes in Intermittent Exotropia Study Group. Presenting features and early management of childhood intermittent exotropia in the UK: inception cohort study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1620-1624.

Coats DK, Olitsky SE, editors. Strabismus surgery and its complications. Berlin: Springer, 2007.

Donahue SP. Pediatric strabismus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1040-1047.

Ganesh A, Pirouznia S, Ganguly SS, et al. Consecutive exotropia after surgical treatment of childhood esotropia: a 40-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 19. [Epub ahead of print]

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Yamada T, et al. Development and initial validation of quality-of-life questionnaires for intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(1):163-168.

Hertle RW, Yang D. Clinical and electrophysiological effects of extraocular muscle surgery on patients with infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS). Semin Ophthalmol. 2006;21:103-110.

Holmes JM, Mutyala S, Maus TL, et al. Pediatric third, fourth, and sixth nerve palsies: a population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:388-392.

Hunter DG, Kelly JB, Buffenn AN, et al. Long-term outcome of uncomplicated infantile exotropia. J AAPOS. 2001;5:352-356.

Ing M. Early surgical alignment for congenital esotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:132-135.

Lambert SR, Lynn M, Sramek J, et al. Clinical features predictive of successfully weaning from spectacles those children with accommodative esotropia. J AAPOS. 2003;7:7-13.

McKenzie JA, Capo JA, Nusz KJ, et al. Prevalence and sex differences of psychiatric disorders in young adults who had intermittent exotropia as children. Arch Opthalmol. 2009;127:743-747.

Mohney BG, Huffaker RK. Common forms of childhood exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2093-2096.

Morris RJ, Scott WE, Dickey CF. Fusion after surgical alignment of longstanding strabismus in adults. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:135-137.

Olitsky SE, Nelson LB. Strabismus disorders. In: Nelson LB, Olitsky SE, editors. Harley’s pediatric ophthalmology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:143-192.

Pathai S, Cumberland PM, Rahi J. Prevalence of and early-life influences on childhood strabismus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010:250-256.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Spontaneous resolution of early-onset esotropia: experience of the Congenital Esotropia Observational Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:109-118.

Shotton K, Elliott S: Interventions for strabismic amblyopia (review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD006461, 2008.

Strominger M. Nystagmus. In: Nelson LB, Olitsky SE, editors. Harley’s pediatric ophthalmology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:475-507.

, positive;

, positive;  , negative; CNNB, congenital stationary night blindness; ERG, electroretinogram; NFL, nerve fiber layer; PHPV, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

, negative; CNNB, congenital stationary night blindness; ERG, electroretinogram; NFL, nerve fiber layer; PHPV, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.