119 Disorders of Early Pregnancy

• Spontaneous abortion (before 12 weeks) will progress to completion with few complications, and incomplete or missed abortion (without shock, fever, or significant bleeding) can be managed expectantly.

• Rh0 immune globulin is effective for up to 12 weeks; no repeated dose is required if bleeding recurs in that time.

• Ectopic pregnancy is responsible for the greatest morbidity and mortality in early pregnancy; ruptured ectopic pregnancy remains responsible for 10% of pregnancy-related deaths.

• Women with a previous ectopic pregnancy have a 15% recurrence rate.

• Serum human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels can vary by as much as 15% between laboratories, and an HCG level should be ordered when suspicion is high despite a negative urine HCG.

• Gestational trophoblastic disease (up to 75% of malignant cases) may develop after a nonmolar pregnancy (spontaneous and elective abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and term gestation); these patients have prolonged bleeding after delivery or miscarriage, with subsequent HCG levels that fail to return to undetectable values.

Spontaneous Abortion

Epidemiology

Spontaneous abortion, also known as miscarriage, occurs when a pregnancy ends before the fetus has reached viability. Viability correlates to a fetus larger than 500 g—or approximately the size at 20 to 22 weeks of gestation. Miscarriage is common and occurs in 25% to 30% of all pregnancies. Eighty percent of miscarriages occur before the 12th week of gestation, and up to 25% occur in pregnancies that are not even recognized clinically; in such cases human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) can be detected in urine but the patient has no missed menses.1

Pathophysiology

The etiology of miscarriage can be classified as either intrinsic or extrinsic to the embryo. Intrinsic factors include genetic abnormalities and congenital conditions. Most cases of spontaneous abortion are due to genetic factors, either anembryonic gestations or chromosomal abnormalities. The majority of these defects arise de novo during fertilization and are not inherited. Genetic factors tend to lead to miscarriage early because of abnormal growth and development.2 In contrast, later miscarriage is more often a result of extrinsic factors.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Spontaneous abortion is classified as threatened, inevitable, incomplete, complete, missed, or septic. Table 119.1 lists characteristics of these categories. Symptoms of spontaneous abortion include vaginal bleeding, suprapubic cramping or pain, and passage of tissue. Bleeding can vary from minor spotting to severe hemorrhage.

| CATEGORY | DEFINITION, CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | ULTRASONOGRAPHIC FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

| Threatened | Bleeding and/or cramping with no passage of tissue, closed os, uterine size appropriate for dates, pregnancy viable | Intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), fetal heart tones (if age appropriate) |

| Inevitable | Open os without passage of products, pregnancy nonviable | IUP or products in the cervical canal |

| Incomplete | Partial passage of products; open os, uterus not well contracted; variable bleeding; pregnancy nonviable | Persistent gestational tissue in the uterus |

| Complete | Products of pregnancy completely passed, closed os, minimal bleeding, uterus well contracted | Empty uterus |

| Missed | Intrauterine demise with no spontaneous passage of products, closed os | Absent fetal cardiac activity or anembryonic gestation, absent heart tones with a crown rump length > 5 mm, absent fetal pole with >18-mm mean sac diameter |

| Septic | Infection complicating any of the previously described categories | Persistent products of conception or hemorrhage within the uterine cavity |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

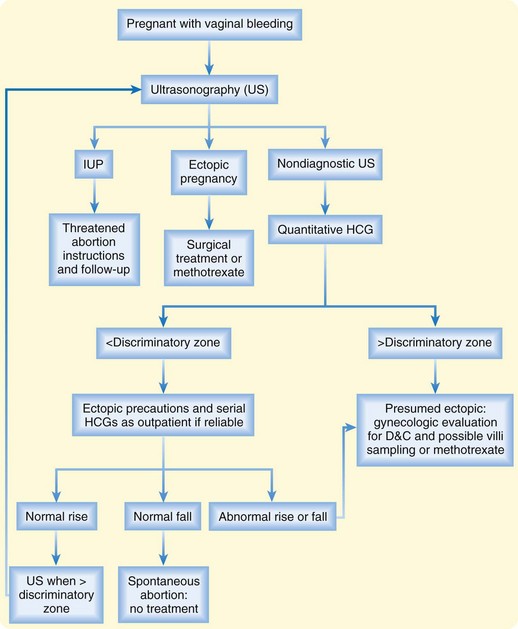

Laboratory studies include a complete blood count, quantitative HCG, and blood type with Rh status. With significant bleeding or other medical disease, coagulation parameters and typing and crossmatching for blood products should be ordered. Ultrasonography is essential for a full diagnosis and for guiding further management (Fig. 119.1). Even if it appears that the patient has passed the embryo, she should undergo ultrasound imaging to evaluate for any retained products.

Treatment

Many patients with spontaneous abortion often need little or no intervention following accurate diagnosis and exclusion of other pathology. Expectant management is the only option for threatened abortion; education and ensuring adequate follow-up care are essential. The presence of fetal heart tones in women with symptoms of threatened abortion is reassuring; less than 5% of women younger than 36 years will miscarry, but this risk rises to 29% in those older than 40.3

Incomplete or missed abortions can be managed expectantly as long as shock, fever, or significant ongoing bleeding are absent. The time course for completion of a spontaneous abortion is highly variable, and patients will need education and routine gynecologic care to plan for dilation and curettage if tissue does not pass spontaneously or if the bleeding becomes heavy. Patients should attempt to collect the products of conception for examination and should undergo subsequent ultrasonography to assess whether all products of conception have passed. Studies have proved the safety of this practice.4 Approximately 90% of patients with incomplete and 76% of those with missed abortions require no surgical treatment when managed expectantly for 4 weeks. Complications occur in 1%, less than in those managed medically.5

Prostaglandins such as misoprostol can effectively induce abortion for pregnancy failure of longer than 12 weeks and may help control bleeding in patients with inevitable or incomplete abortions. The dose of misoprostol is 800 mcg administered vaginally or rectally, but this drug should be given only after consultation with a gynecologist. One large study showed an 84% success rate.6 Misoprostol induces spontaneous abortion, so any possibility of a desired viable pregnancy must be excluded.

Surgical management includes dilation and curettage or dilation and evacuation. Indications are listed in Box 119.1. Risks associated with surgical management are small and include uterine perforation, infection, adhesions, and anesthetic complications.

Rh0 Immune Globulin

Rh0 IG is effective for up to 12 weeks after administration, so patients with recurrent bleeding who already received immunization within that time frame do not need a repeated dose. If significant hemorrhage occurs later in pregnancy, especially in the setting of trauma, additional doses are necessary. Ideally, Rh0 IG is administered within 72 hours of the event leading to fetal-maternal hemorrhage (Box 119.2).

Next Steps in Care and Follow-Up

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Spontaneous Abortion

Miscarriage affects up to one third of pregnancies. Most patients will subsequently have normal pregnancies.

Reassure the patient that in most cases genetic factors are responsible—not patient behavior.

In threatened abortion with a detectable fetal heartbeat, 95% of cases will progress to normal pregnancy.

Women with recurrent miscarriage should receive fertility and genetic evaluation.

Menses will usually resume in about 6 weeks.

Advise 2 weeks of pelvic rest and suggest waiting 2 to 3 months before trying to get pregnant again (although no studies have confirmed either recommendation).

Ectopic Pregnancy

Epidemiology

Ectopic pregnancy, in which the developing embryo implants outside the uterine cavity, is responsible for the greatest morbidity and mortality in early pregnancy. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy in the United States has increased over the past 30 years, and it now accounts for 2% of all pregnancies.7 This increase has been attributed to rising rates of pelvic inflammatory disease, as well as the advent of assisted reproductive technologies.

Pathophysiology

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy are outlined in Box 119.3. Tubal pathology, the most significant risk factor, leads to abnormal transport and implantation of the embryo. The majority of cases arise in women with a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, and women with a previous ectopic pregnancy have a 15% recurrence rate. However, up to 50% of patients with an ectopic pregnancy have no identifiable risk factor.8

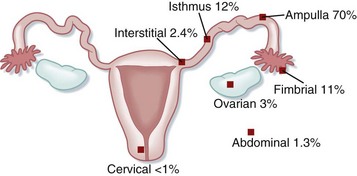

The most common location for ectopic implantation is the fallopian tube, which accounts for 95% of all ectopic pregnancies. The growing blastocyst leads to tubal distention and bleeding into the peritoneal cavity. If the pregnancy continues and is undetected, it can lead to rupture of the tube with subsequent hemorrhage. Less commonly, ectopic pregnancies implant on the ovary, abdominal viscera, or cervix. In these cases, significant hemorrhage or perforation of abdominal structures may occur. See Figure 119.2 for sites of ectopic implantation.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

A heterotopic pregnancy occurs when an intrauterine pregnancy is present simultaneously with an ectopic gestation. Its incidence was at one time estimated to be 1 in 30,000, but the true incidence is unknown. Thus an ectopic gestation can essentially be excluded if an intrauterine pregnancy is demonstrated by ultrasonography. Patients using assisted reproductive techniques have up to a 1% incidence of ectopic pregnancy, highest in patients with transfer of multiple embryos. In these patients, an ectopic gestation should not be excluded solely on the basis of the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy.9

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is listed in Box 119.4. Because of the high potential for morbidity, any patient with abnormal vaginal bleeding or abdominal or pelvic pain should be considered to have an ectopic pregnancy until proved otherwise (see Fig. 119.1).

Quantitative Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Testing

Urinary HCG testing is essential for any woman of childbearing age with abdominal pain. Commercially available kits detect as low as 20 mIU/mL, although there have been case reports of ectopic pregnancy with an undetectable urine HCG level.10 If high clinical suspicion still exists despite negative urinary HCG, a serum HCG test should be ordered.

In normal pregnancy, HCG production begins shortly after fertilization with a peak of about 100,000 mIU/mL at approximately 41 days’ gestational age. In the early weeks of normal pregnancy, HCG levels are expected to double roughly every 48 hours, with a range of 1.4 to 2.1 days. In contrast, HCG levels generally rise more slowly with ectopic and nonviable intrauterine pregnancies. However, in some normal pregnancies, HCG levels may increase as little as 66% over a 48-hour period,11 and up to 17% of ectopic pregnancies have normal doubling times. Patients should have serial measurements done by the same laboratory because interassay variability may be as high as 15%.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonographic Findings Plus Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

Transvaginal sonograms are more likely to be nondiagnostic in women with very low HCG levels, but they may still be useful. Given its safety, transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed on all women with a suspected ectopic pregnancy, even those with HCG levels below the discriminatory zone.12 In a study by Kaplan et al., 19% of patients with HCG levels higher than 1000 mIU/mL at the time of evaluation had transvaginal sonograms diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy.12 The specificity of the ultrasonography findings was 100%.

Patients with HCG levels that plateau or rise by less than double in 72 hours are likely to have either a nonviable intrauterine or an ectopic pregnancy. Repeated transvaginal ultrasonography may be helpful to distinguish the two. Failure to visualize an intrauterine gestation with HCG levels higher than 2000 mIU/mL excludes the possibility of a viable pregnancy. These patients have a high likelihood of having an ectopic gestation and should be treated accordingly.13

Treatment

Methotrexate Therapy

The ideal candidate for methotrexate therapy is relatively asymptomatic with no significant pain or bleeding. A minority of patients will fail treatment or progress to rupture, and the patient must be made aware of these possibilities. Criteria predicting success include diameter less than 3.5 cm, absence of cardiac activity on ultrasonography, and HCG level lower than 5000 mIU/mL. Patients with lower HCG levels tend to have fewer treatment failures.14

Relative contraindications include a high HCG level (>6000 mIU/mL), visible cardiac activity, and a large ectopic mass. Although visible cardiac activity is generally considered a contraindication, one study showed good results despite this finding.15 Absolute contraindications to the use of methotrexate include hemodynamic instability, as well as the factors listed in Box 119.5.

Side effects of methotrexate include stomatitis, conjunctivitis, enteritis, pleuritis, bone marrow suppression, and elevated liver function test results. Thirty percent of patients are affected, but most symptoms are mild and self-limited. The majority of patients will experience some abdominal pain, usually 2 to 3 days after methotrexate administration, because of tubal abortion with subsequent hematoma formation. In contrast to the pain from rupture, this pain is milder, and patients do not have hemodynamic instability or signs of a surgical abdomen. Although only 20% of patients with abdominal pain following methotrexate administration will ultimately need laparoscopy to evaluate for rupture, this subset can be difficult to identify. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed in these patients to evaluate for rupture.16

Tips and Tricks

Methotrexate

Relative contraindications to methotrexate include an HCG level higher than 6000 mIU/mL, visible cardiac activity, and a large ectopic mass because of a high rate of treatment failure.

It is normal for HCG to increase for as long as 4 days after treatment.

On day 7, if HCG has not decreased by 25%, a second dose is needed (15% to 25% of patients).

Most patients will have some abdominal pain 2 to 3 days after administration; this pain is milder than that with rupture. Twenty percent of these patients will need laparoscopy to exclude rupture, however.

Surgical Treatment

A recent review showed the highest success rates with salpingostomy, although single-dose methotrexate therapy had the lowest financial cost and the least impact on quality of life.17 Methotrexate therapy was less costly in patients with HCG levels lower than 1500 mIU/mL. The cost of medical therapy increases in patients with higher HCG levels because of the increased risk for failure, the requirement for multiple doses, and the need for extended monitoring.

Stable patients with nondiagnostic HCG and ultrasound findings are designated as having a pregnancy of unknown location. Expectant management relies on the fact that the spontaneous resolution rate of pregnancies of unknown location is 70%.18 These patients are monitored with serial HCG levels and ultrasonography until a definitive diagnosis can be made. Expectant management is most successful in patients with HCG levels lower than 200 mIU/mL; increased complications occur in those with HCG levels higher than 1500 mIU/mL. However, the complication of tubal rupture can develop in as many as 30%, and it may occur even with decreasing HCG levels, so patients must be aware that treatment failures do occur.

Next Steps in Care and Follow-Up

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Instructions After Receiving Methotrexate

Use acetaminophen for pain instead of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (methotrexate interacts with them).

No intercourse or pelvic examination for 7 days or as advised by the gynecologist (theoretically could rupture the ectopic mass).

No pregnancy for at least one cycle.

Return to the emergency department if the pain increases, especially if it has an acute onset.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Ectopic Pregnancy

Patients should understand that they must obtain follow-up in 2 days for evaluation and repeated HCG measurements because of the potential dangers associated with ectopic pregnancy. (Many patients fail to return for scheduled follow-up.)

Patients should return to the emergency department immediately if any of the following symptoms occur:

The patient should have ready access to emergency care and should avoid distant travel or rural locations.

Patients undergoing fertility treatment with gonadotropins or multiple embryo transfers should be educated about the possibility of recurrence of ectopic pregnancy (e.g., 15% recurrence rate after one ectopic pregnancy, 30% recurrence rate after two ectopic pregnancies).

Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

Epidemiology

The incidence of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) varies from 1 per 1000 pregnancies in the United States to 2 per 1000 pregnancies in Japan.19 Well-established risk factors include nulliparity, personal history of GTD, and maternal age younger than 20 or older than 35 years. Heavy smoking, oral contraceptive use, infertility, and maternal blood types AB or B are also risk factors. Although the disease carried significant morbidity in the past, earlier diagnosis with ultrasonography and more sensitive HCG measurements have led to more successful treatment in recent years.

Pathophysiology

The most common form of GTD is a hydatidiform mole, either partial or complete. A partial mole contains fetal tissue and arises from fertilization of a haploid ovum by two sperm or by a single sperm that then duplicates. In contrast, a complete mole has no fetal tissue or maternal DNA and results from fertilization of an enucleate egg. Up to 15% of complete moles result in malignancy, whereas malignant transformation of a partial mole is less common. Table 119.2 lists the typical characteristics of molar pregnancies.

| CHARACTERISTIC | COMPLETE MOLE | PARTIAL MOLE |

|---|---|---|

| Genetics | Paternal DNA only; 90% 46XX, 10% 46XY | Paternal and maternal DNA; 69XXX, 69XXY, or tetraploid |

| HCG level | Increased | High normal |

| Uterine size | Greater than expected at gestation dates | Normal |

| Fetal tissue | Absent | Present |

| Malignant transformation | 15%-20% | 5% |

HCG, Human chorionic gonadotropin.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Complete moles have a more striking clinical manifestation, with uterine size larger than expected at the stage of pregnancy, absent fetal heart tones, and markedly elevated HCG levels. Vaginal bleeding may be heavy. Medical complications include pregnancy-induced hypertension, early preeclampsia, hyperthyroidism, anemia, and hyperemesis gravidarum.20

As mentioned earlier, GTD may also develop after a nonmolar pregnancy, such as spontaneous and elective abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and term gestation. These patients have prolonged bleeding after delivery or miscarriage, with subsequent HCG levels that fail to return to undetectable measurements. Up to 75% of cases of malignant GTD occur after nonmolar pregnancies. Because placental site trophoblastic tumors may occur years after pregnancy, GTD should be considered in a woman with metastatic disease from an unknown primary site.21

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Molar pregnancy should be included in the differential diagnosis of any patient with first trimester bleeding (see Box 119.4). Abnormally elevated quantitative HCG levels suggest the diagnosis, although there is no absolute level that identifies molar pregnancy. Pelvic ultrasonography is diagnostic in almost all cases. Tissue obtained from uterine evacuation provides histologic confirmation.

Tips and Tricks

Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

Molar pregnancy should be in the differential diagnosis of patients with exaggerated symptoms of pregnancy such as hyperemesis and early preeclampsia.

In patients with spontaneous abortion, the products of conception should be sent for pathologic evaluation because of the possibility of incidental molar pregnancy.

The clinician should consider gestational trophoblastic disease in patients with prolonged or abnormal bleeding after delivery or miscarriage.

Treatment

GTD is likely to be diagnosed only incidentally in the ED during evaluation for spontaneous abortion or ectopic pregnancy. Most patients have few or mild symptoms. Initial ED management includes supportive care for significant hemorrhage, including intravenous fluids and blood products. Rh0 IG should be administered to Rh-negative women. Patients with rupture or torsion of theca lutein cysts may require operative management, although rupture is rare.22

Next Steps in Care and Follow-Up

Posttreatment monitoring for malignant or persistent disease consists of serial HCG measurements. Patients should have frequent pelvic examinations to monitor for local recurrence or vaginal metastases. Patients should be instructed to use contraceptive methods for 12 months because an increase in HCG levels as a result of pregnancy would obscure the monitoring results. Affected patients have an approximately 1% chance for a recurrent mole in future pregnancies, although this risk increases to as high as 28% after two molar pregnancies.23

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Epidemiology

Estimates of the incidence of hyperemesis gravidarum range from 0.3% to 2% of all pregnancies. Risk factors include multiple gestations, GTD, personal or family history of hyperemesis, and female sex of the fetus. Protective factors include advanced maternal age, cigarette smoking, and anosmia. Hyperemesis gravidum is responsible for the highest percentage of hospital admissions during the first half of pregnancy.24,25

Pathophysiology

Hormonal factors are believed to be the pathogenesis. Studies have shown that women with higher HCG and estradiol concentrations have an increased incidence of hyperemesis, but the mechanism is unknown.26 In contrast, no correlation of progesterone levels and symptoms has been shown. Other potential causes such as vitamin deficiencies, gastric motility, and Helicobacter pylori infection have not been consistently linked to the disease. The belief in the past that psychologic issues were causative has no supporting data.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum is one of exclusion given the lack of confirmatory testing available. A careful history should confirm that the symptoms began in the first trimester, with review of systems negative for symptoms consistent with coexistent pathology. Physical examination is aimed at identifying these other conditions. Box 119.6 outlines the differential diagnosis of hyperemesis.

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy is appropriate significant nausea, although patients may have reservations about using these medications. The combination of pyridoxine (10 mg) and doxylamine (12.5 mg) three to four times a day is considered safe; randomized, placebo-controlled studies have shown a 70% reduction in nausea and vomiting. This combination should be considered first-line therapy.27,28

Various antiemetics (Table 119.3) have been used for hyperemesis with good results and reasonable safety data. Antihistamines have the best safety profile, but phenothiazines, metoclopramide, and ondansetron are considered safe as well. Gynecologists may prescribe oral corticosteroids for patients with refractory nausea and vomiting. Studies have shown conflicting results of effectiveness, and the incidence of cleft palate appears to be slightly increased in infants whose mothers received methylprednisolone in the first trimester of pregnancy. Steroids should thus be reserved as a last resort.29,30

| MEDICATION | SAFETY CLASSIFICATION | DOSAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Doxylamine | A | 12.5 mg PO |

| Dimenhydrinate | B | 50-100 mg PO, PR; 50 mg IV |

| Metoclopramide | B | 5-10 mg PO, IV, IM |

| Ondansetron | B | 4-8 mg PO, IV, IM |

| Promethazine | C | 12.5-25 mg IV, IM, PO, PR |

| Prochlorperazine | C | 5-10 mg IV, IM, PO; 25 mg PR |

IM, Intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, orally; PR, parenterally.

Many patients are reluctant to use pharmacotherapy because of a perceived fear of birth defects. These patients may be agreeable to adjunctive therapies such as acupuncture, hypnosis, and powdered ginger. Studies of acupuncture and acupressure have yielded conflicting results,31 whereas hypnosis has been shown to decrease vomiting in patients with hyperemesis. Powdered ginger (250 mg to 1 g/day) is as effective as pyridoxine, but its safety is not well established.32

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Hyperemesis

Daily multivitamin use at the time of conception may decrease the severity of nausea and vomiting.

Avoid triggers such as noxious odors, brushing teeth after eating, and iron supplements.

Eat small, frequent meals rich in protein and carbohydrates and low in fat. Avoid spicy foods.

Eat as soon as you feel hungry.

Drink small amounts of liquids often. Cold, clear, carbonated, and sour liquids are best tolerated.

Aromatic mint tea and teas with lemon or orange flavoring may be helpful.

Next Steps in Care and Follow-Up

Patients should be instructed to return to the ED if vomiting persists or if they experience new symptoms such as abdominal pain and fever. Patients with only mild nausea and vomiting are not at increased risk for low-birth-weight infants or birth defects. Although patients with true hyperemesis do have a higher incidence of low-birth-weight infants, appropriate weight gain later in pregnancy reduces this risk.33

ACEP Clinical Policies Committee and Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Early Pregnancy. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy; critical issues in the initial management of patients presenting to the emergency department in early pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:123–133.

Adhikari S, Blavias M, Lyon M. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy using bedside transvaginal ultrasonography in the ED: a 2-year experience. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:591–596.

Kohn MA, Kerr K, Malkevich D, et al. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin levels and the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy in emergency department patients with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:119–126.

Stein JC, Wang R, et al. Emergency physician ultrasonography for evaluating patients at risk for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:674–683.

1 Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:189–194.

2 Klein J, Stein Z. Epidemiology of chromosomal anomalies in spontaneous abortion: prevalence, manifestation and determinants. In: Bennett MJ, Edmonds DK. Spontaneous and recurrent abortion. Oxford: Blackwell; 1987:29.

3 Deaton JL, Honore GM, Huffman CS, et al. Early transvaginal ultrasound following an accurately dated pregnancy: the importance of finding a yolk sac or fetal heart motion. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2820–2823.

4 Chipchase J, James D. Randomised trial of expectant versus surgical management of spontaneous miscarriage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:840–841.

5 Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873–875.

6 Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, et al. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:761–769.

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1990-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(3):46–48.

8 Tulandi T, Sammour A. Evidence-based management of ectopic pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;12:289–292.

9 Svare J, Norup P, Grove Thomsen S, et al. Heterotopic pregnancies after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer—a Danish survey. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:116–118.

10 Maccato ML, Estrada R, Faro S. Ectopic pregnancy with undetectable serum and urine beta-hCG levels and detection of beta-hCG in the ectopic trophoblast by immunocytochemical evaluation. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:878–880.

11 Kadar N, Caldwell BV, Romero R. A method of screening for ectopic pregnancy and its indications. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:162–166.

12 Kaplan BC, Dart RG, Moskos M, et al. Ectopic pregnancy: prospective study with improved diagnostic accuracy. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:10–17.

13 Mol BWJ, Hajenius PJ, Engelsbel S, et al. Serum human chorionic gonadotropin measurement in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy when transvaginal ultrasound is inconclusive. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:972–981.

14 Lipscomb GH, McCord ML, Stovall TG, et al. Predictors of success of methotrexate treatment in women with tubal ectopic pregnancies. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1974–1978.

15 Lipscomb GH, Bran D, McCord ML, et al. Analysis of three hundred fifteen ectopic pregnancies treated with single dose methotrexate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1354–1358.

16 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Medical management of tubal pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin 3. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1998.

17 Hajenius PJ, Mol BW, Bossuyt PM, et al. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2000. CD000324

18 Yao M, Tulandi T. Current status of surgical and non-surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:421–433.

19 Smith HO. Gestational trophoblastic disease epidemiology and trends. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46:541–556.

20 Sclaerth JB, Morrow CP, Montz FJ, et al. Initial management of hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;158:1299–1306.

21 Tidy JA, Rustin GJ, Newlands ES, et al. Presentation and management of choriocarcinoma after non-molar pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:715–719.

22 Montz FJ, Schlaerth JB, Morrow CP. The natural history of theca lutein cysts. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:247–251.

23 Berkowitz RS, Im SS, Bernstein MR, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: subsequent pregnancy outcome, including repeat molar pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:81–86.

24 Goodwin TM, Montoro M, Mestman JH. Transient hyperthyroidism and hyperemesis gravidarum: clinical aspects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:648–652.

25 Adams MM, Harlass FE, Sarno AP, et al. Antenatal hospitalization among enlisted servicewomen, 1987-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:35–39.

26 Depue RH, Bernstein L, Ross RK, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum in relation to estradiol levels, pregnancy outcome, and other maternal factors: a seroepidemiologic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1137–1141.

27 Vutyavanich T, Wongtra-ngan S, Ruangsri R. Pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:881–884.

28 McKeigue PM, Lamm SH, Linn S, et al. Bendectin and birth defects: I. A meta-analysis of the epidemiologic studies. Teratology. 1994;50:27–37.

29 Yost NP, McIntire DD, Wians FH, Jr., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids for hyperemesis due to pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1250–1254.

30 Carmichael SL, Shaw GM. Maternal corticosteroid use and risk of selected congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1999;86:242–244.

31 Jewell D, Young G. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2003. CD000145

32 Vutyavanich T, Kraisarin T, Ruangsri R. Ginger for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:577–582.

33 Tsang IS, Katz VL, Wells SD. Maternal and fetal outcomes in hyperemesis gravidarum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;55:231–235.