Chapter 687 Disorders Involving Transmembrane Receptors

Achondroplasia Group

Thanatophoric Dysplasia

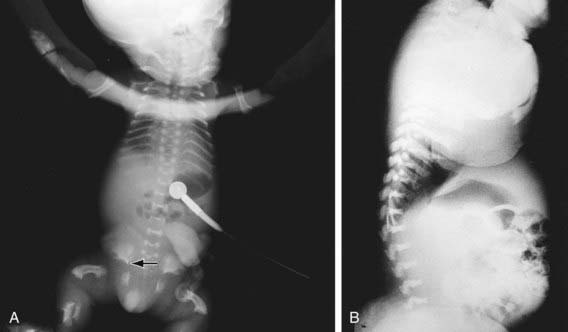

TD (OMIM 187600, 187610) manifests before or at birth. In the former situation, ultrasonographic examination in midgestation or later reveals a large head and very short limbs; the pregnancy is often accompanied by polyhydramnios and premature delivery. Very short limbs, short neck, long narrow thorax, and large head with midfacial hypoplasia dominate the clinical phenotype at birth (Fig. 687-1). The cloverleaf skull deformity known as kleeblattschädel is sometimes found. Newborns have severe respiratory distress because of their small thorax. Although this distress can be treated by intense respiratory care, the long-term prognosis is poor.

Skeletal radiographs distinguish two slightly different forms called TD I and TD II. In the more common TD I, radiographs show large calvariae with a small cranial base, marked thinning and flattening of vertebral bodies visualized best on lateral view, very short ribs, severe hypoplasia of pelvic bones, and very short and bowed tubular bones with flared metaphyses (Fig. 687-2). The femurs are curved and shaped like a telephone receiver. TD II differs mainly in that there are longer and straighter femurs.

Achondroplasia

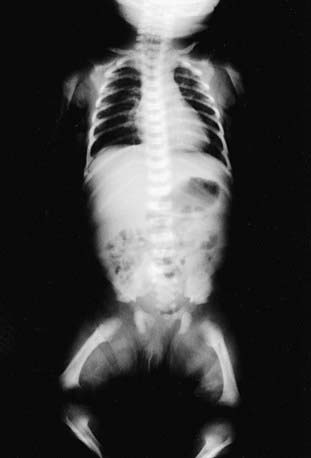

Achondroplasia (OMIM 100800) is the prototype chondrodysplasia. It typically manifests at birth with short limbs, a long narrow trunk, and a large head with midfacial hypoplasia and prominent forehead (Fig. 687-3). The limb shortening is greatest in the proximal segments, and the fingers often display a trident configuration. Most joints are hyperextensible, but extension is restricted at the elbow. A thoracolumbar gibbus is often found. Usually, birth length is slightly less than normal but occasionally plots within the low-normal range.

Diagnosis

Skeletal radiographs confirm the diagnosis (Figs. 687-3 and 687-4). The calvarial bones are large, whereas the cranial base and facial bones are small. The vertebral pedicles are short throughout the spine as noted on a lateral radiograph. The interpedicular distance, which normally increases from the 1st to the 5th lumbar vertebra, decreases in achondroplasia. The iliac bones are short and round, and the acetabular roofs are flat. The tubular bones are short with mildly irregular and flared metaphyses. The fibula is disproportionately long compared with the tibia.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics. Health supervision for children with achondroplasia. Pediatrics. 1995;95:443-451.

Collins WO, Choi SS. Otolaryngologic manifestations of achondroplasia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:237-244.

Ednick M, Tinkle BT, Phromchairak J, et al. Sleep-related respiratory abnormalities and arousal pattern in achomdroplasia during early infancy. J Pediatr. 2009;155:510-515.

Ho NC, Guarnieri M, Brant LJ, et al. Living with achondroplasia: quality of life evaluation following cervico-medullary decompression. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;131:163-167.

Hoover-Fong JE, McGready J, Schulze KJ, et al. Weight for age charts for children with achondroplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:2227-2235.

Horton WA, Hall JG, Hecht JT. Achondroplasia. Lancet. 2007;370:162-172.

Schipani E, Langman CB, Parfitt AM, et al. Constitutively activated receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone–related peptide in Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:708-714.

Sciubba DM, Noggle JC, Marupudi NI, et al. Spinal stenosis surgery in pediatric patients with achondroplasia. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:372-378.