Hip disorders in children

Congenital dislocation of the hip

The incidence of congenital dislocation is between 1 and 2 cases per 1000, but it is four times as frequent in girls as in boys.1 There seems to be a hereditary factor, because there is about a 5% chance of a second child being affected. This rises to 36% if one of the parents also had congenital dislocation of the hip.2

Although there are still questions about its aetiology, the condition seems to occur in the presence of some weakness of the joint capsule and elongation of the ligamentum teres.3 A deficiency of the rim of the acetabulum may also contribute in the development of the disease.4 However, the most important aetiological factor seems to be an imbalance between the action of the psoas muscle and the hip extensors.5 A relative shortening of the psoas presses the head of the femur upwards and laterally when the hip is extended by the contraction of the stronger hip extensors. In the presence of a weakness of the capsule, dislocation then occurs.

It is vital to make the diagnosis of a congenital dislocation as soon after birth as possible. Conservative treatment with an abduction brace6 before the child begins to walk is completely adequate, but after the age of 4 even surgical repositioning is difficult and after the age of 7 it is almost impossible. Without treatment the dislocation may lead to a shorter leg, the formation of a neoacetabulum at the blade of the ilium and the supervention of early arthrosis.

Radiographs are not reliable in making the diagnosis of congenital hip dislocation in newborn babies. Early diagnosis, therefore, relies entirely on clinical tests. Those most used are known as Ortolani’s and Barlow’s tests.7,8 It should be remembered, however, that positive tests only indicate a capsular laxity and therefore the possibility of dislocation. For instance, the incidence of positive Ortolani’s and Barlow’s signs in newborns is about 10–20 per 1000, which is 10 times more than at the age of 2 months, which suggests that there is a tendency towards resolution of the capsular laxity.9

Clinical tests

Ortolani’s test

During this test the luxated hip is replaced manually.

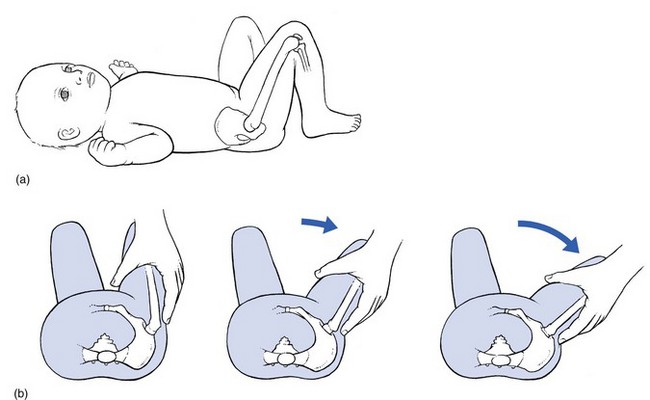

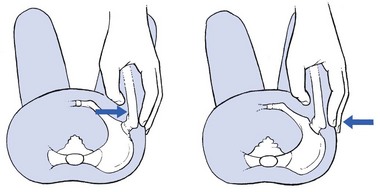

Technique

The baby lies on the back, hips flexed to 90° and the knees completely flexed (Fig. 1a). The examiner grasps the leg with the contralateral hand in such a way that the thumb presses on the inner side of the thigh. The ring and middle fingers are placed along the outer thigh, so that the fingertips touch the trochanter. The other hand fixes the opposite hip. Abduction of the hip is now performed (Fig. 1b). In a subluxated hip, resistance will be felt at 45–60°. The moment the resistance is overcome, the femoral head rides over the acetabular edge and reduces. This is felt by the examiner. This sensation has wrongly been called a click, whereas the feeling is rather that of moving two knuckles of the wrist over each other. Ortoloni described this as a ‘segno dello scatto’ (ridge sign). Under this definition, the sensation has to be felt rather than heard.

Technical investigations

The diagnosis can usually be made with plain radiographs. However, during recent decades sonographic screening examinations have been shown to be superior in the early detection of congenital dislocations of the hip.10,11 In a study of sonographic screening examinations on 4177 newborns, all cases of congenital dislocation of the hip joint were found and classified.12 Consequently, ultrasound screening is currently offered to all newborns in Austria and Germany and to newborns with selected risk factors in the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, Italy and France.12,13,14

Treatment

The majority of unstable hips at birth stabilize in a very short time,15 but since the outcome of an ‘unstable hip’ is impossible to predict, all cases of hip instability in newborns must be taken seriously and treated. Hence, as soon as a positive Ortolani’s or Barlow’s test is found, an abduction brace is given until these clinical signs disappear.16–18

If the diagnosis is made when the child starts to walk, surgical repositioning is required. Surgical reduction is almost impossible after the age of 7 years. If a ‘false acetabulum’ develops at the iliac bone, the functional disability may be small, especially if the disorder is bilateral.19 Pain and serious disability then start only in the fourth or fifth decade, when pseudarthrosis has occurred. If pain is not too severe, treatment can be conservative;20 often some relief is obtained by one or two infiltrations with 50 ml of procaine 0.5% at the posterior aspect of the capsule.21 If pain and disability are too severe, surgery is required.22

Congenital limitation of extension

Treatment consists of stretching the psoas and capsule in the same way as for early osteoarthrosis (see p. 633).

Arthritis of the hip in children

Transient synovitis

Although the pathogenesis of the disorder remains obscure, the conventional view is that it results from ordinary overuse. However, a correlation between transient arthritis and the development of Perthes’ disease has been shown repeatedly.23,24

Sonographic examination, together with X-ray examination, represent the first choices in the evaluation of a capsular pattern in a child and in the follow-up of transient synovitis.25 In transient synovitis there is effusion but the effusion persists for less than 2 weeks. In the early stage of Legg–Calvé–Perthes’ disease the capsular distension persists for more than 6 weeks. A differential diagnosis between transient synovitis and Legg–Calvé–Perthes’ disease is therefore only possible by observing the ultrasonographic course of the disease.26

Treatment is bed rest and non-weight bearing. It is advisable, if excessive intra-articular effusion is demonstrated by ultrasonography, to aspirate the fluid.27 Most cases recover completely and without sequelae after a few weeks of bed rest.28

Septic arthritis

The differential diagnosis with a transient synovitis is difficult.29 A septic arthritis of the hip may have similar early symptoms as a transient synovitis, with the spontaneous onset of progressive hip, groin, or thigh pain; limp or inability to bear weight, fever and irritability.30 Clinical examination shows a capsular pattern. A variety of clinical, laboratory, and radiographic criteria are used to help differentiate septic arthritis from transient synovitis. The four clinical predictors to differentiate between septic arthritis and transient synovitis are: history of fever, pain at rest, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of at least 40 mm per hour, and serum white blood-cell count of more than 12 000 cells per mm3.31 In cases of doubt, hip aspiration should be performed.

Perthes’ disease (pseudocoxalgia)

Perthes’ disease, an idiopathic avascular necrosis/osteonecrosis of the femoral epiphysis, was described in 1910 by Legg as ‘an obscure affection of the hip joint’,32 by Calvé as ‘pseudocoxalgia’33 and by Perthes’ as ‘arthritis deformans juvenilis’.34 The disease affects 4 to 10 year olds, peaking between 5 and 7 years. It affects about four boys for each girl and is bilateral in 10%. Although it is generally accepted that the necrosis is the result of a change in the blood supply to the femoral head,35 there still remains much controversy about the way this occurs. There have been reports suggesting retarded skeletal ageing in relation to the chronological age.36 Some studies have also demonstrated an association with pituitary growth hormone deficiency.37 However the most likely aetiology for Legg–Calvé–Perthes’ disease seems to be the hypothesis of clotting abnormalities with vascular thrombosis.38,39

Treatment and prognosis depend on the age of onset (the younger the age of onset the better the prognosis), the physical signs and the radiological changes.40

Late sequelae of the disease are leg-length shortening and degenerative joint disease that develops in the majority of patients by the sixth or seventh decade of life.41

Slipped epiphysis

Due to gravity, a lysis of the proximal epiphysial junction results in downwards and backwards slipping of the epiphysis in relation to the neck of the femur. This causes a varus position and slight outwards rotation of the leg – coxa vara in adolescence. It is a disorder of teenagers (aged between 12 and 17 years), with an incidence of 5–10 per 100 000.42 The epiphysial junction softens for an unknown reason, although there is strong suspicion that some hormone imbalance could cause the weakening.43,44

Early symptoms can be mild, variable and insidious in onset. Children presenting with a slipped femoral epiphysis may complain of pain in the affected hip or groin, thigh or knee. The pain may be mild or intermittent, or so severe that the child is unable to bear weight.45,46

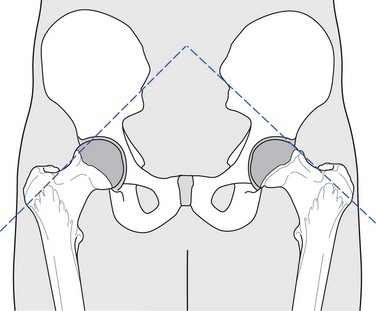

Gait abnormality is frequently observed: the child may walk with a limp and the affected leg in external rotation. Trendelenburg’s sign is usually present. Clinical examination reveals a clear non-capsular pattern with limitation of medial rotation and increase of lateral rotation.47 This can be observed best during bilateral medial rotation in the prone lying position.48 Resisted movements are strong and painless. Diagnosis is confirmed by antero-posterior and lateral hip radiographs which demonstrate the posterior and inferior displacement of the epiphysis relative to the metaphysis49 (Fig. 3).

Treatment and prognosis depend largely on the degree of the slip.50,51 It is therefore vital to make the diagnosis as soon as possible, and a child or teenager in whom epiphysiolysis is suspected should not be allowed to walk around until the result of radiography is known. Epiphysiolysis is an orthopaedic medical emergency and requires immediate relief of weight bearing.52,53 Treatment is surgical and consists of in situ cannulated-screw fixation54 of the slipped capital femoral epiphysis or an open replacement of the femoral head.55,56

Avulsion fractures about the hip

Avulsion fractures occur more commonly in skeletally immature athletes than in adults because young patients’ tendons are stronger than their cartilaginous growth centres. The same stress that causes a muscle strain in an adult can cause an avulsion fracture in an adolescent. These fractures occur at the secondary growth centres, or apophyses, which become separated from the underlying bone. The fractures do not become widely displaced because of the surrounding thick periosteum.57

The mechanism of injury is a sudden, violent muscle contraction or excessive repetitive action across the apophysis. Hip avulsion fractures are common in young sprinters, soccer players and jumpers.58 Patients typically describe local pain and swelling after an extreme effort and report no external trauma.

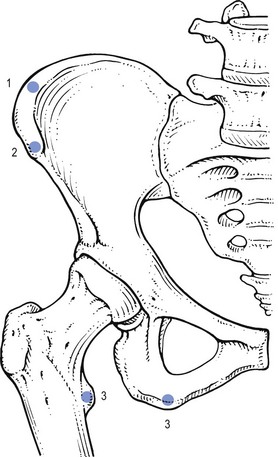

• The anterior superior iliac spine – sartorius

• The anterior inferior iliac spine – rectus femoris

There is also palpable tenderness (and often ecchymosis) at the specific bony sites (Fig. 4).

Fig 4 Bony sites of the pelvis: 1, anterior superior iliac spine;59,60 2, anterior inferior iliac spine;61,62 3, ischial tuberosity; 4, lesser tubercle.63

Plain radiographs reveal the avulsion fracture. It is useful to compare the injured side with the contralateral side. During the healing phase of an avulsion fracture the abundant reactive ossification in the soft tissues may clinically and radiographically be mistaken for neoplasia.59

References

1. MacKenzie, IG, Wilson, JG, Problems encountered in the early diagnosis and management of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1981; 63B:38. ![]()

2. Wynne-Davies, R, Acetabular dysplasia and familial joint laxity. Two etiological factors in congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1970; 52B:704–716. ![]()

3. Catteral, A, What is congenital dislocation of the hip? J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66B:469–471. ![]()

4. Wilkinson, JA, Prime factors in the etiology of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1963; 45B:268–283. ![]()

5. McKibbin, B, The action of the iliopsoas muscle in the newborn. J Bone Joint Surg 1968; 50B:161–165. ![]()

6. Frejka, B. Pravention der angeborene Hüftgelenkensubluxation durch. Abduktionspolster Wiener Med Wochenschr. 1941; 91:523–524.

7. Ortolani, M. Un segno poco noto e sua importanza per la diagnosi precoce di prelussazione congenita dell’anca. Pediatria. 1937; 45:129.

8. Barlow, TG, Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg. 1962;268(45B):292–301. ![]()

9. Visser, JD, Nielsen, HKL. Lichamelijk Onderzoek bij aangeboren heupontwrichting. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1984; 128(26):1217–1220.

10. Graf, R, The diagnosis of congenital hip-joint dislocation by ultrasound compound treatment. Z Orthop Trauma Surg 1980; 97:117–133. ![]()

11. Schule, B, Wissel, H, Neumann, W, Merk, H, Follow-up control of ultrasonographic neonatal screening of the hip. Ultraschall Med. 1999;20(4):161–164. ![]()

12. Rosendahl, K, Toma, P, Ultrasound in the diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. The European approach. A review of methods, accuracy and clinical validity. Eur Radiol 2007; 17:1960–1967. ![]()

13. Woolacott, NF, Puhan, MA, Steurer, J, Kleijnen, J, Ultrasonography in screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns: systematic review. BMJ 2005; 330–1413. ![]()

14. Rosendahl, K, Dezateux, C, Fosse, KR, Aase, H, Aukland, SM, Reigstad, H, Alsaker, T, Moster, D, Lie, RT, Markestad, T, Immediate treatment versus sonographic surveillance for mild hip dysplasia in newborns. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e9–16. ![]()

15. Coleman, SS. Congenital Dysplasia and Dislocation of the Hip. St. Louis: Mosby; 1978.

16. Vasser, JD, Functional treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55(suppl):206. ![]()

17. Lempichi, A, Wierusz-Koslowska, Kruczynski, J, Abduction treatment in late diagnosed congenital dislocation of the hip. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;61(suppl):236. ![]()

18. Burger, BJ, Burger, JD, Bos, CF, et al, Frejka pillow and Becker device for congenital dislocation of the hip. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(3):305–311. ![]()

19. Crawford, AW, Slovek, RW, Fate of the untreated congenitally dislocated hip. Orthop Trans 1978; 2:73. ![]()

20. Wedge, JH, Wasylenko, MJ, The natural history of congenital disease of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1979; 61B:334–338. ![]()

21. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

22. Henderson, RS, Osteotomy for unreduced congenital dislocations of the hips in adults. J Bone Joint Surg 1970; 52B:468. ![]()

23. Kemp, HBS, Perthes disease. Ann R Coll Surg 1973; 5:18. ![]()

24. Inoue, A, Freeman, MAR, Vernon-Roberts, B, Mizuno, S, The pathogenesis of Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg 1976; 58B:453. ![]()

25. de Pellegrin, M, Fracassetti, D, Ciampi, P, Coxitis fugax. The role of diagnostic imaging. Orthopäde. 1997;26(10):858–867. ![]()

26. Konermann, W, de Pellegrin, M, The differential diagnosis of juvenile hip pain in the ultrasonographic picture. Transient coxitis, Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease, epiphysiolysis of the femur head. M Orthopäde. 1993;22(5):280–287. ![]()

27. Bernd, L, Niethard, FU, Graf, J, Kaps, HP, Transient hip joint inflammation. Z Orthop Grenzgeb. 1992;130(6):529–535. ![]()

28. Monty, CP, Prognosis of ‘observation hip in children ’. Archs Dis Child 1962; 37:539. ![]()

29. Zamzam, MM, The role of ultrasound in differentiating septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15(6):418–422. ![]()

30. Jung, ST, Rowe, SM, Moon, ES, Song, EK, Yoon, TR, Seo, HY, Significance of laboratory and radiologic findings for differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23:368–372. ![]()

31. Kocher, MS, Mandiga, R, Zurakowski, D, Barnewolt, C, Kasser, JR, Validation of a clinical prediction rule for the differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86-A:1629–1635. ![]()

32. Legg, AT, An obscure affection of the hip joint. Boston Med Surg J 1910; 162:202. ![]()

33. Calvé, J. Sur une forme particulière de pseudocoxalgie. Rev Chir. 1910; 42:54.

34. Perthes, G. C. Über Arthritis deformans juvenilis. Dtsch Z Chir. 1910; 107:111.

35. Trueta, J, Normal vascular anatomy of human femoral head during growth. J Bone Joint Surg 1975; 39B:358. ![]()

36. Harrison, MHM, Turner, MH, Jacobs, P, Skeletal immaturity in Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg 1976; 58B:37. ![]()

37. Rayner, PHW, Schwalbe, SL, Hall, DJ, An assessment of endocrine function in boys with Perthes’ disease. Clin Orthop 1986; 209:124–128. ![]()

38. Atsumi, T, Yamano, K, Muraki, M, Yoshihara, S, Kajihara, T, The blood supply of the lateral epiphyseal arteries in Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82:392–398. ![]()

39. Wall, EJ, Legg–Calvé–Perthes’ disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11(1):76–79. ![]()

40. Menelaus, MB, Lessons learned in the management of Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease. Clin Orthop 1986; 209:41–48. ![]()

41. Yrjonen, T, Long-term prognosis of Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;8(3):169–172. ![]()

42. Aronsson, DD, Loder, RT, Breuer, GJ, Weinstein, SL, Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14:666–679. ![]()

43. Murray, AW, Wilson, NIL, Changing incidence of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a relationship with obesity? J Bone Joint Surg 2008; 90B:92–94. ![]()

44. Tachdjian, MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990.

45. Matava, MJ, Patton, CM, Luhmann, S, Gordon, JE, Schoenecker, PL, Knee pain as the initial symptom of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an analysis of initial presentation and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19(4):455–460. ![]()

46. Jinguishi, S, Suenaga, E, Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: etiology and treatment. J Orthop Sci 2004; 9:214–219. ![]()

47. Van den Berg, ME, Keesen, W, Van der Hoeven, H, Epiphysiolysis van de heupkop. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1992; 136:1339–1343. ![]()

48. Weigall, P, Vladusic, S, Torode, I, Slipped upper femoral epiphysis in children – delays to diagnosis. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(3):151–153. ![]()

49. Aronsson, DD, Loder, RT, Breuer, GJ, Weinstein, SL, Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14:666–679. ![]()

50. Dunn DM. Severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis and open replacement by cervical osteotomy. Proceedings of the Third Open Scientific Meeting of the Hip Society. St. Louis, 1975:125–6.

51. Ordeberg, G, Hansson, LI, Sandström, S, Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in southern Sweden. Long-term result with closed reduction and hip plaster. Spica Clin Orthop 1987; 220:148–154. ![]()

52. Rahme, D, Comley, A, Foster, B, Cundy, P, Consequences of diagnostic delays in slipped capital epiphysis. Pediatric Orthop B 2006; 15:93–97. ![]()

53. Green, DW, Reynolds, RAK, Khan, SN, Tolo, V, The delay in diagnosis of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a review of 102 patients. HSSJ 2005; 1:103–106. ![]()

54. Givon, U, Bowen, JR, 1999 Chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis: treatment by pinning in situ. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;8(3):216–222. ![]()

55. Dunn, DM, Angel, JC, Replacement of the femoral head by open operation in severe adolescent slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg 1978; 60B:394. ![]()

56. Aronson, DD, Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: the importance of physeal stability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993; 75:1134–1140. ![]()

57. Gross, ML, Nasser, S, Finerman, GAM. Hip and pelvis. In: DeLee JC, Drez D, Jr., eds. Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1994:1063–1085.

58. Kling, ThF. Pelvic and acetabular fractures. In: Steinberg ME, ed. The Hip and its Disorders. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1991:173–197.

59. Draper, DO, Dustman, AJ, Avulsion fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine in a collegiate distance runner. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73(9):881–882. ![]()

60. Lambert, MJ, Fligner, DJ, Avulsion of the iliac crest apophysis: a rare fracture in adolescent athletes. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(7):1218–1220. ![]()

61. Schothorst, AE, Avulsion fractures of the inferior–anterior iliac spine. Arch Chir Neerl 1978; 1:55–59. ![]()

62. Mader, T, Avulsion of the rectus femoris tendon: an unusual type of pelvic fracture. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1990;6(3):198–199. ![]()

63. Theologis, TN, Epps, H, Latz, K, Cole, WG, Isolated fractures of the lesser trochanter in children. Injury. 1997;28(5-6):363–364. ![]()