Chapter 539 Disorders and Anomalies of the Scrotal Contents

Undescended Testis (Cryptorchidism)

Clinical Manifestations

A disorder of sexual development (DSD; aka intersex) should be suspected in a newborn phenotypic male with bilateral nonpalpable testes, as the child could be a virilized girl with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (Chapter 570). In a boy with midpenile or proximal hypospadias and a palpable undescended testis, DSD is present in 15%, and the risk is 50% if the testis is nonpalpable.

The risk of a germ cell malignancy (Chapter 497) developing in an undescended testis is 2-4 times higher than that in the general population and is approximately 1/80 with a unilateral undescended testis and 1/40-50 for bilateral undescended testes. Testicular tumors are less common if the orchiopexy is performed before 10 yr of age, but they still occur, and adolescents should be instructed in testicular self-examination. The peak age for developing a testis tumor is 15-45 yr. The most common tumor developing in an undescended testis in an adolescent or adult is a seminoma (65%); after orchiopexy, seminomas represent only 30% of testis tumors. Orchiopexy seems to reduce the risk of seminoma. Whether early orchiopexy reduces the risk of developing cancer of the testis is controversial, but it is uncommon for testis tumors to occur after orchiopexy performed before the age of 2 yr. The contralateral scrotal testis is not at increased risk for malignancy.

Treatment

In boys with a nonpalpable testis, diagnostic laparoscopy is performed in most centers. This procedure allows safe and rapid assessment of whether the testis is intra-abdominal. In most cases, orchiopexy of the intra-abdominal testis located immediately inside the internal inguinal ring is successful, but orchiectomy should be considered in more difficult cases or when the testis appears to be atrophic. A 2-stage orchiopexy sometimes is needed in boys with a high abdominal testis. Boys with abdominal testes are managed with laparoscopic techniques at many institutions. Testicular prostheses are available for older children and adolescents when the absence of the gonad in the scrotum might have an undesirable psychologic effect. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a saline testicular implant. Solid silicone “carving block” implants also are used (Fig. 539-1). Placement of testicular prostheses early in childhood is recommended for boys with anorchia (absence of both testes).

Scrotal Swelling

Scrotal swelling may be acute or chronic and painful or painless. Abrupt onset of painful scrotal swelling necessitates prompt evaluation because some conditions, such as testicular torsion and incarcerated inguinal hernia, require emergency surgical management. The differential diagnosis is shown in Tables 539-1 and 539-2.

Testicular (Spermatic Cord) Torsion

Treatment

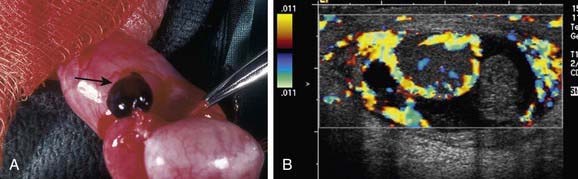

Treatment is prompt surgical exploration and detorsion. If the testis is explored within 6 hr of torsion, up to 90% of the gonads survive. Testicular salvage decreases rapidly with a delay of >6 hr. If the degree of torsion is 360 degrees or less, the testis might have sufficient arterial flow to allow the gonad to survive, even after 24-48 hr. Following detorsion the testis is fixed in the scrotum with nonabsorbable sutures, termed scrotal orchiopexy, to prevent torsion in the future. The contralateral testis also should be fixed in the scrotum because the predisposing anatomic condition often is bilateral. If the testis appears nonviable, orchiectomy is performed (Fig. 539-2A). Some adolescents do not undergo prompt evaluation and treatment and present with “late phase testicular torsion,” in which the spermatic cord contracts and the testis is high in the scrotum and nontender (see Fig. 539-2B). Fertility is reduced in men with a history of spermatic cord torsion in adolescence, irrespective of whether detorsion or orchiectomy is performed.

Spermatic cord torsion also can occur in the fetus or neonate. This condition results from incomplete attachment of the tunica vaginalis to the scrotal wall and is “extravaginal.” When torsion occurs in utero, the baby usually is born with a large, firm, nontender testis. Usually the ipsilateral hemiscrotum is ecchymotic (Fig. 539-3). In these cases, the testis rarely is viable because torsion was a remote event. However, the contralateral testis is at increased risk for torsion until 1 mo beyond term. Most pediatric urologists recommend exploration to establish the diagnosis, remove the necrotic testis, or rarely salvage a viable testis, and anchor the contralateral testis.

Torsion of the Appendix Testis

Torsion of the appendix testis is the most common cause of testicular pain in boys 2-10 yr but is rare in adolescents. The appendix testis is a stalk-like structure that is a vestigial embryonic remnant of the müllerian (paramesonephric) ductal system that is attached to the upper pole of the testis. When it undergoes torsion, progressive inflammation and swelling of the testis and epididymis occurs, resulting in testicular pain and scrotal erythema. The onset of pain usually is gradual. Palpation of the testis usually reveals a 3- to 5-mm tender indurated mass on the upper pole (Fig. 539-4A). In some cases, the appendage that has undergone torsion may be visible through the scrotal skin, in the “blue dot” sign. In some boys, distinguishing torsion of the appendix from testicular torsion is difficult. In such cases, a testicular flow scan or color Doppler ultrasonography is useful because testicular blood flow should be normal or increased. In such cases, the radiologist often recognizes epididymal enlargement and makes the diagnosis of epididymitis, reflecting the inflammatory reaction (see Fig. 539-4B).

Epididymitis

Acute inflammation of the epididymis is an ascending retrograde infection from the urethra, through the vas into the epididymis. This condition causes acute scrotal pain, erythema, and swelling. It is rare before puberty and should raise the question of a congenital abnormality of the wolffian duct, such as an ectopic ureter entering the vas. In younger boys, the responsible organism often is Escherichia coli (Chapter 192). After puberty, bacterial epididymitis becomes progressively more common and is the principal cause of acute painful scrotal swelling in young sexually active men. Urinalysis usually reveals pyuria. Epididymitis can be infectious (usually gonococcus or chlamydia; Chapters 185 and 218), but often the organism remains undetermined. Additional etiologies include familial Mediterranean fever, enterovirus, and adenoviruses. Treatment consists of bed rest and antibiotics (Chapter 192). Differentiation from torsion can be difficult, and surgical exploration usually is required in children.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP; Chapter 478) is a systemic vasculitis that involves multiple organ systems and that can involve the kidney and spermatic cord. When the spermatic cord is involved, typically there is bilateral painful scrotal swelling with purpuric lesions involving the scrotum. Scrotal sonography should show normal testicular blood flow. Treatment is directed toward systemic treatment of the HSP.

Varicocele

A varicocele is a congenital condition in which there is abnormal dilation of the pampiniform plexus in the scrotum (Fig. 539-5). Dilation of the pampiniform venous plexus results from valvular incompetence of the internal spermatic vein. Approximately 15% of men have a varicocele; of these men, approximately 15% are subfertile. Varicocele is the most common (and virtually the only) surgically correctable cause of subfertility in men. A varicocele is found in 5-15% of adolescent boys, but it rarely is diagnosed in boys <10 yr old, because the varicocele becomes distended only after the increased blood flow associated with puberty occurs. Varicoceles occur predominantly on the left side, are bilateral in 2% of cases, and rarely involve the right side only. A varicocele in a boy <10 yr or one on the right side might indicate an abdominal or retroperitoneal mass; an abdominal sonogram or CT scan should be performed in such cases.

Hydrocele

Etiology

A hydrocele is an accumulation of fluid in the tunica vaginalis (Fig. 539-6). From 1-2% of neonates have a hydrocele. In most cases, the hydrocele is noncommunicating (the processus vaginalis was obliterated during development). In such cases, the hydrocele fluid disappears by 1 yr of age. If there is a persistently patent processus, the hydrocele persists and becomes progressively larger during the day and is small in the morning. A rare variant of a hydrocele is the abdominoscrotal hydrocele, in which there is a large, tense hydrocele that extends into the lower abdominal cavity. In some older boys, a noncommunicating hydrocele can result from an inflammatory condition within the scrotum, such as testicular torsion, torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, or testicular tumor. The long-term risk of a communicating hydrocele is the development of an inguinal hernia. Some older boys and adolescents also develop a hydrocele. In some cases hydrocele develop acutely after an episode of scrotal trauma or epididymo-orchitis, whereas others develop more insidiously.

Treatment

Most congenital hydroceles resolve by 12 mo of age following reabsorption of the hydrocele fluid. If the hydrocele is large and tense, however, early surgical correction should be considered, because it is difficult to verify that the child does not have a hernia, and large hydroceles rarely disappear spontaneously. Hydroceles persisting beyond 12-18 mo usually are communicating and should be repaired. Surgical correction is similar to a herniorrhaphy (Chapter 338). Through an inguinal incision, the spermatic cord is identified, the hydrocele fluid is drained, and a high ligation of the processus vaginalis is performed. If an older boy has a large hydrocele, often diagnostic laparoscopy can be performed to determine whether there is a patent processus vaginalis, and if the internal ring is closed, then the hydrocele may be corrected with a scrotal incision.

Testicular Tumor

Testicular and paratesticular tumors can occur at any age, even in the newborn. Approximately 35% of prepubertal testis tumors are malignant; most commonly they are yolk sac tumors, although rhabdomyosarcoma and leukemia also can occur in this age group. In adolescents, 98% of painless solid testicular masses are malignant (Chapter 497). Most manifest as a painless, hard testicular mass that does not transilluminate. Scrotal ultrasonography should be performed to confirm the finding of a testicular mass and it can help to delineate the type of testis tumor. Serum tumor markers, including α-fetoprotein and β-HCG, should be drawn. Definitive therapy includes surgical exploration through an inguinal incision. In most cases, a radical orchiectomy, consisting of removal of the entire testis and spermatic cord, is performed. In a prepubertal boy, if the ultrasonographic study or surgical exploration suggests that the tumor is localized and benign, such as a teratoma or epidermoid cyst, testis-sparing surgery with removal only of the mass may be appropriate.

Al-Salem AH. Intrauterine testicular torsion: a surgical emergency. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1887-1891.

Arap MA, Vincentini FC, Cocuzza M, et al. Late hormonal levels, semen parameters, and presence of antisperm antibodies in patients treated for testicular torsion. J Androl. 2007;28:528-532.

Bassel YS, Scherz HC, Kirsch AJ. Scrotal incision orchiopexy for undescended testes with or without a patent processus vaginalis. J Urol. 2007;177:1516-1518.

Diamond DA, Zurakowski D, Bauer SB, et al. Relationship of varicocele grade and testicular hypotrophy to semen parameters in adolescents. J Urol. 2007;178:1584-1588.

Ferlin A, Zuccarello D, Zuccarello B, et al. Genetic alterations associated with cryptorchidism. JAMA. 2008;300:2271-2276.

Hayn MH, Herz DB, Bellinger MF, et al. Intermittent torsion of the spermatic cord portends an increased risk of acute testicular infarction. J Urol. 2008;180:1729-1732.

Kaye JD, Levitt SB, Friedman SC, et al. Neonatal torsion: a 14-year experience and proposed algorithm for management. J Urol. 2008;179:2377-2383.

Kaye JD, Shapiro EY, Levitt SB, et al. Parenchymal echo texture predicts testicular salvage after torsion: potential impact on the need for emergent exploration. J Urol. 2008;180:1733-1736.

Keoghane SR, Sullivan ME. Investigating and managing chronic scrotal pain. BMJ. 2010;341:c6716.

Kollin C, Karpe B, Hesser U, et al. Surgical treatment of unilaterally undescended testes: testicular growth after randomization to orchiopexy at age 9 months or 3 years. J Urol. 2007;178:1589-1593.

Mouriquand P. The nomad testis. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:3.

Pettersson A, Akre O, Richiardi L, et al. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of testicular cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1835-1841.

Pohl HG, Joyce GF, Wise M, et al. Cryptorchidism and hypospadias. J Urol. 2007;177:1646-1651.

Ritzen EM, Bergh A, Bjerknes R, et al. Nordic consensus on treatment of undescended testes. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:638-643.

Schneck FX, Bellinger MF. Abnormalities of the testes and scrotum and their surgical management. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. ed 9. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007:3791-3798.

Somani BK, Watson G, Townell N. Testicular torsion. BMJ. 2010;341:c3213.

Stec AA, Tanaka ST, Adams MC, et al. Orchiopexy for intra-abdominal testes: factors predicting success. J Urol. 2009;182:1917-1920.

Taskinen S, Taskinen M, Rintala R. Testicular torsion: orchiectomy or orchiopexy? J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4:210-213.

Wood HM, Elder JS. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction. J Urol. 2009;181:452-461.