Chapter 13 Dislocations of the Elbow in Children

Introduction

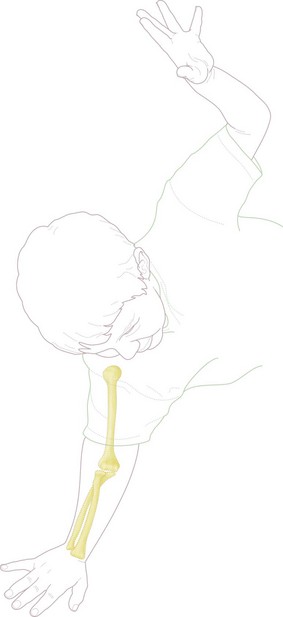

Falls on the outstretched hand are common in childhood and occur in some toddlers on a daily basis. Approximately 65% of all fractures in children are to the upper limb, with the vast majority the result of indirect forces, following a fall on the outstretched hand (Fig. 13.1).2 The most common site of injury is the wrist and hand, with the elbow region accounting for approximately 10% of the total. Although elbow dislocations are much less common than fractures,3 it is important to make a prompt diagnosis since in the majority of patients this will enable closed reduction and result in a rapid return of normal function and appearance of the elbow. Delayed diagnosis or inappropriate management may require open surgical management and result in permanent functional loss.

Prevalence and associated injuries

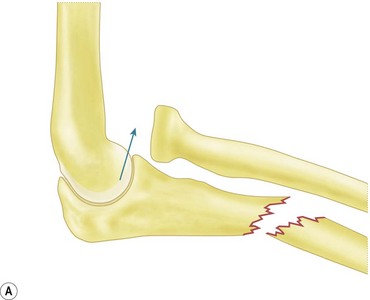

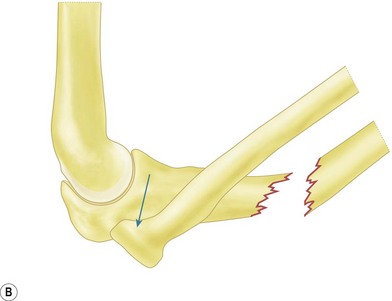

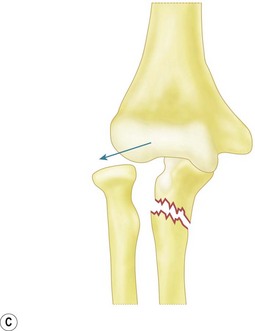

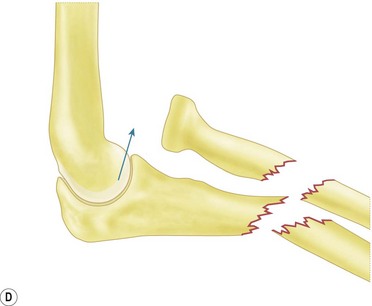

A study of 1579 elbow injuries in skeletally immature individuals from Gothenberg, Sweden, found only 45 dislocations, giving a prevalence of only 3%.4 Subluxation of the radial head (pulled elbow) usually occurs in children aged between 2 and 4 years, while dislocations tend to occur around the time of physeal closure (12–14 years). The most common dislocation is posterior and may be accompanied by almost any fracture or combination of fractures, the most frequent being fracture separation of the medial epicondyle, fracture of the lateral condyle and fracture of the radial neck. Less common fractures occur to the coronoid and medial condyle. The Monteggia fracture dislocation is the most common fracture–dislocation combination in childhood (Fig. 13.2). Isolated dislocation of the radial head is uncommon.

Summary Box 13.1

Pulled elbow

Background/aetiology

Pulled elbow occurs in toddlers and children aged 1–6 years, with a peak incidence at age 2–4 years.5 The diagnosis is not tenable outside these narrow age limits. The injury is caused by longitudinal traction on the extended elbow, in a child young enough to have sufficient intrinsic elbow laxity to allow the radial head to slide partially out of the annular ligament. The toddler tries to go in one direction, while the parent pulls in another. As Mercer Rang wryly observed, the wonder is not that some children get a pulled elbow but that ‘it is remarkable that not all children experience a pulled elbow’.1

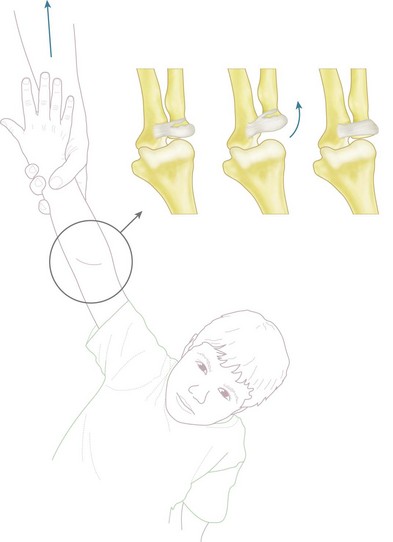

Originally it was thought that the injury occurred with the elbow extended and the forearm supinated. However, it is now widely believed that subluxation results when the pronated, extended forearm of an infant has forcible traction applied through the longitudinal axis. The typical scenario is a parent suddenly pulling their child by the arm. The annular ligament may simply be stretched or partially torn, and occasionally subluxates into the radiocapitellar joint (Fig. 13.3). The head of the radius subluxates distally but not beyond the equator, or maximal circumference, of the head. If it goes beyond this point, studies show that reduction becomes difficult, and these may go on to Monteggia type fracture–dislocations of the forearm with dislocation of the radial head.6

Outcome and literature review

The success rate of manipulation is very high and all pulled elbows appear eventually to self-relocate, without any long-term sequelae.7 Delayed presentation may result in failed manipulation. Failed manipulation or delayed return in using the arm should prompt a search for other injuries and include repeat examination and radiographs. Ultrasonography can provide inconsistent results8 and is very rarely used in our emergency department. Treatment of failed manipulation in a collar and cuff in flexion for a few days will result in successful relocation in all late-presenting cases and open reduction is very rarely necessary.9 A technique of forced pronation at the wrist, with or without flexion at the elbow, has been advocated by some authors. In a randomized control trial, parents perceived this technique to be less painful for their child.7

Recurrent episodes occur in 5–39% of children until the annular ligament becomes stronger and stiffer.10,11 Age at initial presentation of less than 24 months is a risk factor for recurrent subluxation,12 and some advocate immobilizing all manipulated elbows in a flexed and supinated position for 2 days to ensure a successful outcome.13

Summary Box 13.2

Elbow dislocations

Background/aetiology

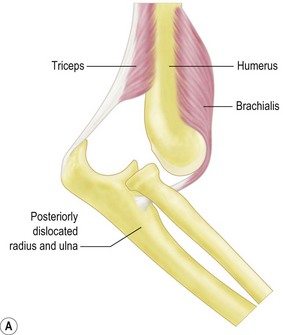

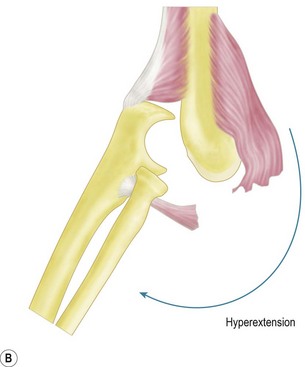

Posterolateral dislocation of the elbow is typically the result of indirect trauma and most frequently occurs as the result of a fall on the outstretched hand. The mechanism is thought to begin with the elbow in either the semi-flexed or hyperextended position. The medial structures of the elbow joint are integral to joint stability, and axial force from a fall is transmitted to the medial elbow by the medial crista of the trochlear, exaggerating the natural valgus carrying angle of the elbow. When this valgus force is applied to either the hyperextended or semi-flexed elbow, the medial collateral ligament is torn or the medial epicondyle and common flexor origin are avulsed. In addition, the coronoid process is also at risk of fracturing. The anterior capsule is commonly disrupted, exposing the articular surface and increasing the danger of soft tissue or neurovascular structures being interposed during reduction. Disruption of the posterior capsule may also occur and contribute to the risk of recurrent dislocation.14 The brachialis muscle, in its position between the anterior capsule and the more superficial neurovascular structures, is at risk during dislocation of the elbow but is particularly liable to be torn if hyperextension forces are applied in order to achieve reduction of the joint (Fig. 13.4). Tearing of the brachialis may expose the median nerve and brachial artery, which are then stretched directly over the trochlea. Median nerve entrapment may occur during reduction, as originally described by Hallet.15

Arterial damage to the main brachial trunk is rare.16,17 However, complete rupture, an intimal tear or simple kinking into the elbow joint can occur because of the tethering effect of the collaterals and surrounding soft tissue restraints. Complete arterial rupture is more likely in open injuries. The most common vascular injury is a compartment syndrome resulting from swelling and secondary compromise to the brachial artery and collateral circulation. The risk factors are severe closed trauma, delay in treatment, closed reduction and immobilization in flexion in a complete cast. Severe ulnar nerve injury is less common now than previously described owing to the increasing recognition that entrapment of the medial epicondyle within the joint may also trap the ulnar nerve.18 Ulnar nerve injuries are usually transient.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Anteroposterior (AP) radiographs show the distal humerus superimposed distally over the proximal forearm, with the proximal radius and ulna usually displaced in a posterior and lateral direction. Lateral radiographs confirm a posterior dislocation of the elbow (Fig. 13.6A, B).

Given that more than 50% of elbow dislocations in children have associated fractures, the radiographs must be carefully examined for bony injuries (medial epicondyle, radial neck and coronoid).19 Less common fractures include lateral condyle, lateral epicondyle, medial condyle and olecranon.

Management and rehabilitation

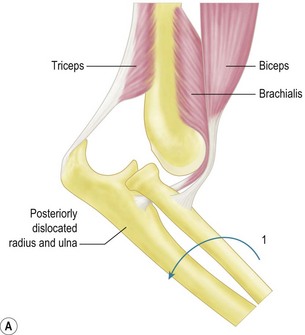

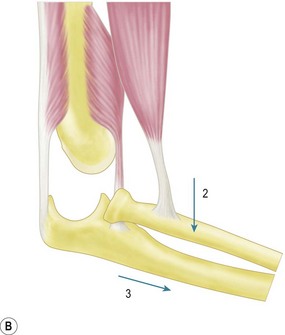

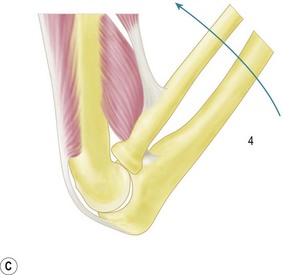

The majority of elbow dislocations are managed by closed reduction. The principle of reduction is to counteract the muscle forces that are maintaining the dislocation. These are the brachialis and biceps anteriorly and the triceps posteriorly. These forces must be overcome so as to allow the coronoid process of the ulna and the radial head to pass unimpeded from posterior to anterior. Indeed, if not free to do so, these osseous landmarks are at risk of fracture. To unlock the radial head and coronoid process from behind the distal humerus, some authors have previously advocated initial hyperextension.20 This, however, has been shown to produce excessive force on an already stretched brachialis, which can cause rupturing of the muscle and the anterior capsule. Hypersupination is more useful and is often the critical step to unlock the radial head from behind the distal humerus.18

The two major techniques to reduce the elbow can be classified as ‘push’ and ‘pull’. First, traction longitudinally down the arm and supination of the forearm aids unlocking of the proximal radius and ulna. The now free radial and ulnar articular surfaces are then either pushed (from pressure on the olecranon) or pulled (via longitudinal traction on the forearm), enabling relocation of the joint. This is done while the elbow is being flexed, which helps maintain the reduction (Fig. 13.5).

Reduction is first assessed clinically by the correction of the fixed deformity, restoration of range of motion and reformation of the normal posterior bony landmarks. The stability of reduction should also be confirmed and the position maintained by a posterior plaster slab, extending from below the shoulder to the metacarpophalangeal joints. This is maintained for a period of 3 weeks in the majority of first time dislocators. A collar and cuff are applied to support the plaster slab. Repeat radiographs must be undertaken to confirm the reduction and a repeat neurovascular examination performed after the child has fully recovered from sedation or anaesthesia (Fig. 13.6).

Closed reduction is successful in more than 90% of isolated posterior dislocations.19

Indications for open reduction include failed closed reduction. This may occur due to interposed tissue, of which incarceration of the medial epicondyle within the joint is by far the most common. Additional indications are the treatment of associated fractures, existing open injury or the investigation of neurovascular compromise. Primary ligament repair is not an appropriate indication as studies have shown that the outcome is inferior to closed treatment.21,22

Outcome and literature review

Closed reduction of a posterior dislocation of the elbow in children is effective in more than 90% of cases.19 A better outcome is expected in closed reduction versus open reduction, but the severity of associated injuries needs to be considered when interpreting these data.23 Prompt reduction increases the success rate.24 The majority of children will regain a near normal range of motion and full function. A loss of between 5° and 10° of elbow extension is quite common but the majority of children and parents will be unaware of this deficit.18 However, children and parents should always be advised about this risk when consent is being taken for reduction of the dislocation.

The common causes of more severe stiffness are delayed diagnosis, immobilization beyond 3 weeks, and vigorous and early physiotherapy, particularly if this involves passive stretching and missed incarceration of the medial epicondyle necessitating delayed open reduction.25

Complications of treatment

Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture

This is the most serious complication but is fortunately uncommon. Various types of direct and indirect arterial injury may be implicated but the final common pathway is compartment syndrome. Damage to the brachial artery can occur in the form of complete rupture, an intimal tear or entrapment within the joint.26 Arterial rupture is more common in open injuries. Unfortunately, the presence of a Doppler pulse at the wrist does not rule out arterial compromise,17 and if distal ischaemia is still suspected the cast and dressings should be removed, the elbow extended and an arteriogram considered. Prompt exploration and fasciotomy should, however, never be delayed if clinically compartment syndrome is suspected. It is important to remember that the collateral arterial supply may be disrupted in elbow dislocations and therefore cannot always be relied upon in the event of a brachial artery injury.27

Neurological compromise

Three types of median nerve entrapment associated with elbow dislocation have been described by Hallet.15 Types 1 and 2 occur in association with a fracture of the medial epicondyle.

Median nerve entrapment can be difficult to diagnose, as there is often little associated pain, and neurological examination for sensorimotor loss in children can be unreliable. The combination of a medial epicondyle fracture and median nerve dysfunction is a strong indication for early exploration and neurolysis.28

Transposition of the ulnar nerve in the acute setting has been suggested by some26 but is rarely necessary.29,30

Recurrent dislocation

This is rare, but when it occurs the initial dislocation is thought to have happened in the paediatric age group.23,31 Recurrent dislocations have been shown to be associated with deficiencies in the posterolateral soft tissues of the elbow joint. A technique to address these defects was proposed by Osborne and Cotterill.14 The same authors, however, along with others, caution against surgical intervention if the recurrent dislocations are infrequent.

Other patterns of dislocation

Anterior dislocations

Anterior dislocations in children are very rare (<2%).23 In contrast to posterior dislocations, the mechanism of injury may involve a direct blow to the semi-flexed elbow. Clinically, the elbow is locked in extension with severe pain and swelling. The incidence of neurovascular complications involving the brachial artery and median nerve is much higher than in posterior dislocations.

Divergent dislocation

Divergent dislocations are a rare subgroup of elbow dislocation in children, involving all three articulations: humero-ulnar, radiocapitellar and radio-ulnar. The humerus is wedged between the proximal ulna and radius. Only significant soft tissue injury and disruption of the proximal radio-ulnar joint will allow such intrusion of the distal humerus between the proximal forearm bones (Fig. 13.7).

The first radiologically documented case was reported by DeLee in 1981.32 Two distinct types of divergent dislocation have been proposed: mediolateral (transverse) and AP. These refer to the direction of dislocation of the two forearm bones.

The child typically presents with pain, swelling and an inability to move the elbow after a fall on the outstretched hand. The elbow is locked in about 30° of flexion. Good-quality AP and lateral radiographs are often difficult to obtain. Many of the views in published reports and in our own series are oblique.33–35 The radius and ulna dislocate proximally and the distal humerus becomes interposed between them. For this to happen, the proximal radio-ulnar joint must be disrupted, along with a significant portion of the proximal interosseous ligament.

The severity of ligamentous and capsular damage in this injury is confirmed by the ease with which the dislocation is reduced. Longitudinal traction is applied to the semi-extended forearm, while the proximal radius and ulna are compressed together. The elbow is immobilized in 90° of flexion in a long-arm posterior plaster slab for 3 weeks. The long-term outcome of posterior divergent elbow dislocation is satisfactory.33,34 Recurrent instability is rare despite the severe associated soft tissue damage.

Proximal radio-ulnar translocation

Delayed diagnosis is common and as a result closed reduction has a high failure rate. Open reduction via a posterolateral approach is required on a more frequent basis than with any other type of elbow dislocation in children.36 Associated fractures that may be present involve the radial neck and coronoid process.

Congenital dislocations

Congenital elbow dislocations can be difficult to distinguish from neglected acute dislocations. The radiological changes are similar, with marked atrophy of the humeral condyles and the semilunar notch of the olecranon. The diagnosis of a congenital dislocation is supported by the presence of syndromes such as Larsen’s,37 nail–patella or Ehlers–Danlos38 and of dislocations in other joints. Range of motion and function in association with a syndromic congenital dislocation is often surprisingly good. The majority require no treatment unless pain develops in association with a prominent radial head at skeletal maturity.

Distal humeral physeal separation

Distal humeral physeal separation is a Salter–Harris type I injury of the distal humeral growth plate. It may be confused with an elbow dislocation and supracondylar fracture of the humerus. The triangular relationship between the tip of the olecranon and the humeral epicondyles is maintained. This injury has a peak incidence from birth to 2 years. Confusion may occur when presented with a neonate that is not using one arm. An elbow dislocation is often queried but is not seen in this age group. A good clinical outcome can be expected after a 2- to 4-week period of cast immobilization, even without reduction being attempted.39

The Monteggia fracture–dislocation

Background/aetiology

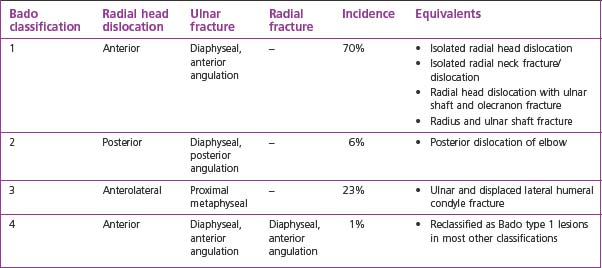

The Monteggia fracture–dislocation is a dislocation of the radial head accompanied by a fracture of the ulnar shaft. It occurs more commonly in children than in adults but unfortunately is a diagnosis that is often missed due to those who first see the child being unaware of this common childhood injury pattern.40,41 Late diagnosis delays treatment, impairs the outcome and frequently leads to litigation. The injury complex occurs as the result of indirect forces when the child falls on the outstretched hand. In published series the peak age at presentation is 5–12 years, with usually more boys than girls and more injuries to the non-dominant upper limb.42

This type of fracture dislocation was first described by Giovanni Monteggia in 1814. His name was given to the injury by Perrin in 1901. A further classification system based on the direction of the radial head dislocation and associated ulnar and radial fracture patterns was proposed by Jose Bado, of Uruguay, in the late 1950s.43 It is this classification system of Monteggia fracture–dislocations that is widely used today.

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

In an acute injury pain is typical and the child is reluctant to use the affected elbow. Swelling and bruising should be noted, and focal tenderness may be present anteriorly. Range of motion of the elbow is markedly reduced, particularly pronation and supination. However, in younger children with joint laxity and a greenstick fracture or plastic bowing of the ulna, the physical signs may be relatively minor and settle quickly (Fig. 13.9). In the emergency department attention is often directed to the ulnar fracture, and it is important that the elbow is also carefully examined and adequate radiographs obtained.

Clinical Pearl 13.4

In younger children with joint laxity and a greenstick fracture or plastic bowing of the ulna, the physical signs may be relatively minor and settle quickly (Fig. 13.9). Attention is often directed to the ulnar fracture in the emergency department and the elbow may not be examined or adequate radiographs obtained.

Management and rehabilitation

Prior to treatment it is imperative classify the injury correctly in order to identify accurately the forces required to reduce the injury and maintain the reduction. Closed reduction is the management of choice in the majority of acute Monteggia lesions.44 Reduction of the ulnar fracture, followed by flexion and supination of the elbow and forearm, usually results in reduction of the radial head unless the fracture reduction is unstable. In this situation the radial head may be difficult to reduce or unstable following reduction.

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Management of the ulnar fracture is crucial. Plastic bowing and greenstick fractures are inherently stable and can be realigned by closed reduction. Displaced transverse fractures are best managed by intramedullary fixation with an elastic nail. The stability of the radial head dislocation depends on anatomical realignment of the ulnar fracture (Fig. 13.10).

Outcome and literature review

Prompt diagnosis and appropriate closed treatment will result in normal appearance and function of the elbow in the majority of children.23,42,45 Delayed diagnosis, however, results in an increased reliance on open reduction, and has suboptimal outcomes.45 A recent study on the pathology of the annular ligament in acute Monteggia lesions has shown that it is interposed in the radiocapitellar joint in the majority of cases.46 Despite this, excellent outcomes can be expected from closed reduction of the radial head provided that the associated fractures are appropriately treated.5,47–49 If open reduction of the radial head is required, there is an increased risk of functional deficit due to scarring and heterotopic ossification.47

Complications of treatment

The most common complication of Monteggia lesions is late diagnosis.50 The patient often presents fortuitously following a knock to the elbow, with mild and intermittent pain together with limited range of motion and stiffness. The carrying angle of the elbow is increased and the radial head is palpable as a lump on the anterolateral aspect of the elbow. Management is dictated by the interval between injury and presentation, the state of the radial head, the degree of malunion of the ulna, the age of the child, and the wishes of the parents and child. Early is better than delayed surgical reconstruction and younger patients have better outcomes. However, unlike the management of the acute lesion, which is predictably good, management of the chronic lesion is predictably unpredictable and has a high complication rate, even in expert hands.45 The longer the interval between injury and reconstruction, the more likely it will be that an open reduction of the radial head will be required, with reconstruction of the annular ligament. The risk of redislocation, neurovascular injury, degenerative change and stiffness in this situation is substantial.45 For this reason reconstruction of the chronic Monteggia lesion should be performed by surgeons with a special interest in the area.

Management of the chronic Monteggia lesion: options, outcomes and literature review

Chronic Monteggia lesions are defined as those presenting 3 or more months after an acute injury. Initially symptoms are mild and intermittent and include mild pain, slightly decreased range of motion and mild valgus deformity. Tardy ulnar nerve and posterior interosseous nerve palsies are uncommon initially but are seen as late features.51 Untreated, the dislocated radial head becomes hypertrophic and progressively convex in profile. The capitellum flattens and the range of elbow flexion and extension reduces.

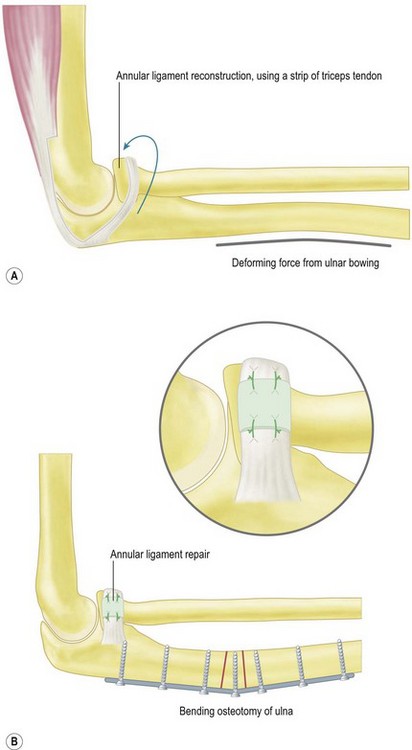

Management of the chronic Monteggia lesion includes symptomatic treatment, radial head excision, repair or reconstruction of the annular ligament, closed or open reduction of the radial head and osteotomy of the ulna and/or radius.44,51–54 Of these, the most successful reconstructions usually combine open reduction of the radial head with reconstruction of the annular ligament and corrective osteotomy of the ulnar deformity.55 Earlier descriptions emphasized annular ligament reconstruction using imported local tissue, such as a strip of triceps fascia, as in the classical Bell Tawse procedure56 and its variants.57 Results of these older procedures were uncertain and had a high incidence of subluxation and stiffness. In long-term follow-up, notching of the radial neck was noted and suggested that the reconstructed annular ligament was either too tight or not isometric.55 Although the annular ligament is considered the most important structure in maintaining the enlocation of the radial head,58 recent literature suggests that without an ulnar osteotomy to correct the ulnar malunion it is likely that the radial head will redislocate.50,52

Other publications emphasize repair rather than replacement of the annular ligament,48,59 combined with a posterior, bending and lengthening osteotomy of the ulna. These newer procedures are associated with improved long-term results, although they do not abolish the risk of subluxation and degenerative change (Fig. 13.11).

Another recent study has shown that prognosis is affected by age and the interval from acute injury to time of reconstruction. Age of less than 12 years at the time of reconstruction and an interval from acute injury to reconstruction of less than 3 years were associated with better long-term outcomes.51

Radial head excision is considered a salvage procedure, with good results in terms of pain relief, but only appropriate for patients who have reached skeletal maturity. This is because of the well-documented risk of proximal radial migration following radial head excision in skeletally immature patients.60

Summary Box 13.4

1 Rang M. Elbow. In: Rang M, editor. Children’s fractures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1983.

2 Hanlon CR, Estes WLJr. Fractures in childhood, a statistical analysis. Am J Surg. 1954;87(3):312-323.

3 Kuhn MA, Ross G. Acute elbow dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39(2):155-161.

4 Henrikson B. Supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children: a late review of end-results with special reference to the cause of deformity, disability and complications. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1966;369:1-72.

5 Green NE, Van Zeeland NL. Fractures and dislocations about the elbow. In: Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, editors. Skeletal trauma in children. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:207-282.

6 Salter RB, Zaltz C. Anatomic investigations of the mechanism of injury and pathologic anatomy of ‘pulled elbow’ in young children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971;77:134-143.

7 Green DA, Linares MY, Garcia Pena BM, et al. Randomized comparison of pain perception during radial head subluxation reduction using supination-flexion or forced pronation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(4):235-238.

8 Scapinelli R, Borgo A. Pulled elbow in infancy: diagnostic role of imaging. Radiol Med. 2005;110(5–6):655-664.

9 Kaplan RE, Lillis KA. Recurrent nursemaid’s elbow (annular ligament displacement) treatment via telephone. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):171-174.

10 Snellman O. Subluxatio capituli radii; yleinen lasten vamma. Suomen Laakarilehti. 1958;13(28):1363-1367.

11 Quan L, Marcuse EK. The epidemiology and treatment of radial head subluxation. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(12):1194-1197.

12 Teach SJ, Schutzman SA. Prospective study of recurrent radial head subluxation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(2):164-166.

13 Taha AM. The treatment of pulled elbow: a prospective randomized study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(5–6):336-337.

14 Osborne G, Cotterill P. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1966;48(2):340-346.

15 Hallett J. Entrapment of the median nerve after dislocation of the elbow: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63-B(3):408-412.

16 Thomas PJ, Noellert RC. Brachial artery disruption after closed posterior dislocation of the elbow. Am J Orthop (Chatham, NJ). 1995;24(7):558-560.

17 Hofammann KE3rd, Moneim MS, Omer GE, et al. Brachial artery disruption following closed posterior elbow dislocation in a child: assessment with intravenous digital angiography. A case report with review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;184:145-149.

18 Wilkins KE. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow region. In: Rockwood CA, editor. Fractures in children. 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1996:658-669.

19 Carlioz H, Abols Y. Posterior dislocation of the elbow in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4(1):8-12.

20 Tachdijan MO. Paediatric orthopaedics. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1972.

21 Josefsson PO, Gentz CF, Johnell O, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of ligamentous injuries following dislocations of the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;214:165-169.

22 Josefsson PO, Gentz CF, Johnell O, et al. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment of ligamentous injuries following dislocation of the elbow joint: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(4):605-608.

23 Rasool MN. Dislocations of the elbow in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2004;86(7):1050-1058.

24 Royle SG. Posterior dislocation of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;269:201-204.

25 Neviaser JS, Wickstrom JK. Dislocation of the elbow: a retrospective study of 115 patients. South Med J. 1977;70(2):172-173.

26 Linscheid RL, Wheeler DK. Elbow dislocations. JAMA. 1965;194(11):1171-1176.

27 Louis DS, Ricciardi JE, Spengler DM. Arterial injury: a complication of posterior elbow dislocation. A clinical and anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1974;56(8):1631-1636.

28 Rao SB, Crawford AH. Median nerve entrapment after dislocation of the elbow in children: a report of 2 cases and review of literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;312:232-237.

29 Roberts PH. Dislocation of the elbow. Br J Surg. 1969;56(11):806-815.

30 Fowles JV, Slimane N, Kassab MT. Elbow dislocation with avulsion of the medial humeral epicondyle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1990;72(1):102-104.

31 Hassmann GC, Brunn F, Neer CS2nd. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1975;57(8):1080-1084.

32 DeLee JC. Transverse divergent dislocation of the elbow in a child: case report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1981;63(2):322-323.

33 Altuntas AO, Balakumar J, Howells RJ, et al. Posterior divergent dislocation of the elbow in children and adolescents: a report of three cases and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):317-321.

34 Basanagoudar P, Pace A, Ross D. Unusual dislocation of the elbow in a child: review of literature. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2008;65(2):E18-E20.

35 Nanno M, Sawaizumi T, Ito H. Transverse divergent dislocation of the elbow with ipsilateral distal radius fracture in a child. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(2):145-149.

36 Gillingham BL, Wright JG. Convergent dislocation of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;340:198-201.

37 Larsen LJ, Schottstaedt ER, Bost FC. Multiple congenital dislocations associated with characteristic facial abnormality. J Pediatr. 1950;37(4):574-581.

38 Almquist EE, Gordon LH, Blue AI. Congenital dislocation of the head of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1969;51(6):1118-1127.

39 Jacobsen S, Hansson G, Nathorst-Westfelt J. Traumatic separation of the distal epiphysis of the humerus sustained at birth. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2009;91(6):797-802.

40 Fowles JV, Sliman N, Kassab MT. The Monteggia lesion in children: fracture of the ulna and dislocation of the radial head. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1983;65(9):1276-1282.

41 Freedman L, Luk K, Leong JC. Radial head reduction after a missed Monteggia fracture: brief report. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1988;70(5):846-847.

42 Letts M, Locht R, Wiens J. Monteggia fracture–dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1985;67(5):724-727.

43 Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967;50:71-86.

44 Belangero WD, Livani B, Zogaib RK. Treatment of chronic radial head dislocations in children. Int Orthop. 2007;31(2):151-154.

45 Rodgers WB, Waters PM, Hall JE. Chronic Monteggia lesions in children: complications and results of reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1996;78(9):1322-1329.

46 Tan JW, Mu MZ, Liao GJ, et al. Pathology of the annular ligament in paediatric Monteggia fractures. Injury. 2008;39(4):451-455.

47 Korner J, Hansen M, Weinberg A, et al. Monteggia fractures in childhood: diagnosis and management in acute and chronic cases. Eur J Trauma. 2004;30(6):361-370.

48 Horii E, Nakamura R, Koh S, et al. Surgical treatment for chronic radial head dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2002;84-A(7):1183-1188.

49 Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Pediatric fractures of the forearm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432:65-72.

50 Gyr BM, Stevens PM, Smith JT. Chronic Monteggia fractures in children: outcome after treatment with the Bell Tawse procedure. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13(6):402-406.

51 Nakamura K, Hirachi K, Uchiyama S, et al. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes after open reduction for missed Monteggia fracture–dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2009;91(6):1394-1404.

52 Wang MN, Chang WN. Chronic posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: thirteen cases treated by open reduction, ulnar osteotomy, and annular ligament reconstruction through a Boyd incision. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(1):1-5.

53 Attarian DE. Annular ligament reconstruction in chronic posttraumatic radial head dislocation in children. Contemp Orthop. 1993;27(3):259-264.

54 Hasler CC, Von Laer L, Hell AK. Open reduction, ulnar osteotomy and external fixation for chronic anterior dislocation of the head of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2005;87(1):88-94.

55 Seel MJ, Peterson HA. Management of chronic posttraumatic radial head dislocation in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19(3):306-312.

56 Bell Tawse AJ. The treatment of malunited anterior Monteggia fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1965;47(4):718-723.

57 Lloyd-Roberts GC, Bucknill TM. Anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: aetiology, natural history and management. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1977;59-B(4):402-407.

58 Stoll TM, Willis RB, Paterson DC. Treatment of the missed Monteggia fracture in the child. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1992;74(3):436-440.

59 Hui JH, Sulaiman AR, Lee HC, et al. Open reduction and annular ligament reconstruction with fascia of the forearm in chronic Monteggia lesions in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(4):501-506.

60 Dormans JP, Rang M. The problem of Monteggia fracture–dislocations in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1990;21(2):251-256.