Chapter 434 Diseases of the Pericardium

The heart is enveloped in a bilayer membrane, the pericardium, which normally contains a small amount of serous fluid. The pericardium is not vital to normal function of the heart, and primary diseases of the pericardium are uncommon. However, the pericardium may be affected by a variety of conditions (Table 434-1), often as a manifestation of a systemic illness and can result in serious, even life-threatening, cardiac compromise.

Table 434-1 ETIOLOGY OF PERICARDIAL DISEASE

CONGENITAL

INFECTIOUS

NONINFECTIOUS

434.1 Acute Pericarditis

Robert Spicer and Stephanie Ware

Diagnosis

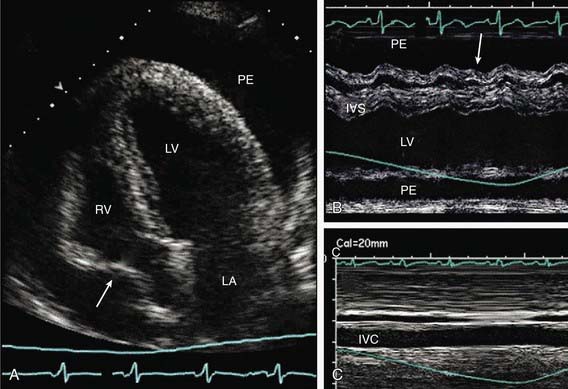

Although the chest x-ray findings in a patient with pericarditis without effusion are usually normal, in the presence of a significant effusion, cardiac enlargement will be seen and cardiac contour may be unusual (Erlenmeyer flask). Echocardiography is the most sensitive technique for identifying the size and location of a pericardial effusion. Compression and collapse of the right atrium and/or right ventricle are present with cardiac tamponade (Fig. 434-1). Abnormal diastolic filling parameters have also been described in cases of tamponade.

Differential Diagnosis

Noninfectious Pericarditis

Systemic inflammatory diseases including autoimmune, rheumatologic, and connective tissue disorders may involve the pericardium and result in serous pericardial effusions. Pericardial inflammation may be a component of the type II hypersensitivity reaction seen in patients with acute rheumatic fever. It is often associated with rheumatic valvulitis and responds quickly to antiinflammatory agents including steroids. Tamponade is very uncommon (Chapters 176.1 and 432).

434.2 Constrictive Pericarditis

Robert Spicer and Stephanie Ware

Constrictive pericarditis may be difficult to distinguish clinically from restrictive cardiomyopathy as both conditions result in impaired myocardial filling (Chapter 433.3). Echocardiography may be helpful in distinguishing constrictive pericardial disease from restrictive cardiomyopathy, but magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic imaging are more sensitive in detecting abnormalities of the pericardium. In rare instances, exploratory thoracotomy with direct examination of the pericardium may be required to confirm the diagnosis.

Dal-Bianco JP, Sengupta PP, Mookadam F, et al. Role of echocardiography in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:24-33. quiz 103–104

Demmler GJ. Infectious pericarditis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:165-166.

Karlberg N, Jalanko H, Perheentupa J, et al. Mulibrey nanism: clinical features and diagnostic criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41:92-98.

Kuhn B, Peters J, Marks GR, et al. Etiology, management, and outcome of pediatric pericardial effusions. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:90-94.

Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006;113:1622-1632.

Parikh SV, Memon N, Echols M, et al. Purulent pericarditis. Medicine. 2009;88:52-65.

Roy CL, Minor MA, Brookhart MA, et al. Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade? JAMA. 297, 2007. 1810–1181

Yeh T-T, Yang Y-H, Lin Y-T, et al. Cardiopulmonary involvement in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a 20-year retrospective analysis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:525-531.