Chapter 651 Diseases of the Dermis

Keloid

Clinical Manifestations

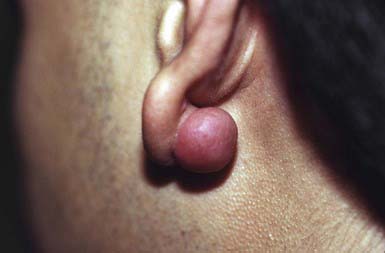

A keloid is a sharply demarcated, benign, dense growth of connective tissue that forms in the dermis after trauma. The lesions are firm, raised, pink, and rubbery; they may be tender or pruritic. Sites of predilection are the face, earlobes (Fig. 651-1), neck, shoulders, upper trunk, sternum, and lower legs. In both keloids and hypertrophic scars, new collagen forms over a much longer period than in wounds that heal normally.

Striae Cutis Distensae (Stretch Marks)

Granuloma Annulare

Clinical Manifestations

This common dermatosis occurs predominantly in children and young adults. Affected children are usually healthy. Typical lesions begin as firm, smooth, erythematous papules. They gradually enlarge to form annular plaques with a papular border and a normal, slightly atrophic or discolored central area up to several centimeters in size. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body, but mucous membranes are spared. Favored sites include the dorsum of the hands (Fig. 651-3) and feet. The disseminated papular form is rare in children. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare tends to develop on the scalp and limbs, particularly in the pretibial area. These lesions are firm, usually nontender, skin-colored nodules. Perforating granuloma annulare is characterized by the development of a yellowish center in some of the superficial papular lesions as a result of transepidermal elimination of altered collagen.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica

Clinical Manifestations

This disorder manifests as erythematous papules that evolve into irregularly shaped, sharply demarcated, yellow, sclerotic plaques with central telangiectasia and a violaceous border. Scaling, crusting, and ulceration are frequent. Lesions develop most commonly on the shins (Fig. 651-4). Slow extension of a given lesion over the years is usual, but long periods of quiescence or complete healing with scarring may occur.

Lichen Sclerosus

Clinical Manifestations

Lichen sclerosus manifests initially as shiny, indurated, ivory-colored papules, often with a violaceous halo. The surface shows prominent dilated pilosebaceous or sweat duct orifices that often contain yellow or brown plugs. The papules coalesce to form irregular plaques of variable size, which may develop hemorrhagic bullae in their margins. In the later stages, atrophy results in a depressed plaque with a wrinkled surface. This disorder occurs more commonly in girls than in boys. Sites of predilection in girls are the vulvar (Fig. 651-5), perianal, and perineal skin. Extensive involvement may produce a sclerotic, atrophic plaque of hourglass configuration; shrinkage of the labia and stenosis of the introitus may result. Vaginal discharge precedes vulvar lesions in approximately 20% of patients. In boys, the prepuce and glans penis are often involved, usually in association with phimosis; most boys with the disorder were not circumcised early in life. Sites elsewhere on the body that are most commonly involved include the upper trunk, the neck, the axillae, the flexor surfaces of wrists, and the areas around the umbilicus and the eyes. Pruritus may be severe.

Differential Diagnosis

In children, lichen sclerosus is most frequently confused with focal morphea (Chapter 154), with which it may coexist. In the genital area, it may be mistakenly attributed to sexual abuse.

Morphea

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Morphea is a sclerosing condition of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue of unknown etiology.

Clinical Manifestations

Morphea is characterized by solitary, multiple or linear circumscribed areas of erythema that evolve into indurated, sclerotic, atrophic plaques (Fig. 651-6), later healing, or “burning out” with pigment change. It is seen more commonly in females. The most common types of morphea are plaque and linear. Morphea can affect any area of skin. When confined to the frontal scalp, forehead, and midface in a linear band, it is referred to as en coup de sabre. When located on one side of the face, it is called progressive hemifacial atrophy. These forms of morphea carry a poorer prognosis because of the associated underlying musculoskeletal atrophy that can be cosmetically disfiguring. Linear morphea over a joint may lead to restriction of mobility (Fig. 651-7). Pansclerotic morphea is a rare severe disabling variant.

Scleredema (Scleredema Adultorum, Scleredema of Buschke)

Differential Diagnosis

Scleredema must be differentiated from scleroderma (Chapter 154), morphea, myxedema, trichinosis, dermatomyositis, sclerema neonatorum, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Lipoid Proteinosis (Urbach-Wiethe Disease, Hyalinosis Cutis et Mucosae)

Macular Atrophy (Anetoderma)

Cutis Laxa (Dermatomegaly, Generalized Elastolysis)

Clinical Manifestations

There may be widespread folds of lax skin, or changes may be mild and limited in extent, resembling anetoderma. Patients with severe cutis laxa have characteristic facial features, including an aged appearance with sagging jowls (bloodhound appearance) (Fig. 651-8), a hooked nose with everted nostrils, a short columella, a long upper lip, and everted lower eyelids. The skin is also lax elsewhere on the body and may resemble an ill-fitting suit. Hyperelasticity and hypermobility of the joints are not present as they are in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Many infants have a hoarse cry, probably as a result of laxity of the vocal cords. Tensile strength of the skin is normal.

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a group of genetically heterogeneous connective tissue disorders. Affected children appear normal at birth, but skin hyperelasticity, fragility of the skin and blood vessels, delayed wound healing, and joint hypermobility (Fig. 651-9) develop. The essential defect is a quantitative deficiency of fibrillar collagen.

Classification

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome has been reclassified into 6 clinical forms.

Arthrochalasia (Cola1a Gene, Type A; Col1a2 Gene, Type B; Previously Eds Types VIIA and B—Arthrochalasis Multiplex Congenita)

Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Clinical Manifestations

Onset of skin manifestations often occurs during childhood, but the changes produced by early lesions are subtle and may not be recognized. The characteristic pebbly, “plucked chicken skin” cutaneous lesions are 1-2 mm, asymptomatic, yellow papules that are arranged in a linear or reticulated pattern or in confluent plaques. Preferred sites are the flexural neck (Fig. 651-10), axillary and inguinal folds, umbilicus, thighs, and antecubital and popliteal fossae. As the lesions become more pronounced, the skin acquires a velvety texture and droops in lax, inelastic folds. The face is usually spared. Mucous membrane lesions may involve the lips, buccal cavity, rectum, and vagina. There is involvement of the connective tissue of the media, and intima of blood vessels, Bruch membrane of the eye, and endocardium or pericardium may result in visual disturbances, angioid streaks in Bruch membrane, intermittent claudication, cerebral and coronary occlusion, hypertension, and hemorrhage from the gastrointestinal tract, uterus, or mucosal surfaces. Women with PXE have an increased risk of miscarriage in the 1st trimester. Arterial involvement generally manifests in adulthood, but claudication and angina have occurred in early childhood.

Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

Clinical Manifestations

This is an unusual skin disorder in which 1- to 3-mm, firm, skin-colored, keratotic papules tend to cluster in arcuate and annular patterns on the posterolateral neck and limbs (Fig. 651-11) and, occasionally, on the face and trunk. Onset usually occurs in childhood or adolescence. A papule consists of a circumscribed area of epidermal hyperplasia that communicates with the underlying dermis by a narrow channel. There is a great increase in the amount and size of elastic fibers in the upper dermis, particularly in the dermal papillae. Approximately 30% occur in association with osteogenesis imperfecta, Marfan syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, scleroderma, acrogeria, and Down syndrome. EPS has also occurred in association with penicillamine therapy.

Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Clinical Manifestations

RPC usually manifests in early childhood as small papules on the dorsal areas of the hands and forearms, elbows, knees, and, sometimes, face and trunk. Over a period of several weeks, the papules enlarge to 5-10 mm, become umbilicated, and develop keratotic plugs in their centers (Fig. 651-12). Individual lesions resolve spontaneously in 2-4 mo, leaving hypopigmented macules or scars. Lesions may recur in crops; may undergo a linear Koebner phenomenon; and may form in response to cold temperatures or superficial trauma such as abrasions, insect bites, and acne lesions.

Mucopolysaccharidoses (Chapter 82)

In several of the mucopolysaccharidoses, thick, rough, inelastic skin, particularly on the extremities, and generalized hirsutism are characteristic but nonspecific features. Telangiectasias on the face, forearms, trunk, and legs have been observed in Scheie and Morquio syndromes. In some patients with Hunter syndrome, ivory-colored, distinctive firm papulonodules with a corrugated surface texture are grouped into symmetric plaques on the upper trunk (Fig. 651-13), arms, and thighs. Onset of these unusual lesions occurs in the 1st decade of life, and spontaneous disappearance has been noted.

Mastocytosis

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Mastocytosis encompasses a spectrum of disorders that range from solitary cutaneous nodules to diffuse infiltration of skin associated with involvement of other organs (Table 651-1). All of the disorders are characterized by aggregates of mast cells in the dermis. There are 4 types of mastocytoses: solitary mastocytoma; urticaria pigmentosa (2 forms); diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis; and telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. The 2 forms of urticaria pigmentosa are the childhood variant, which resolves without sequelae, and the form that may start in either childhood or adult life and is associated with a mutation (most commonly the D816V mutation) in the stem cell factor gene. Stem cell factor (mast cell growth factor), which can be secreted by keratinocytes, stimulates the proliferation of mast cells and increases the production of melanin by melanocytes. The local and systemic manifestations of the disease are due, at least in part, to release of histamine and heparin from mast cell granules; although heparin is present in significant amounts in mast cells, coagulation disturbances occur only rarely. The vasodilator prostaglandin D2 or its metabolite appears to exacerbate the flushing response. Serum tryptase values are often elevated.

Table 651-1 MASTOCYTOSIS CLASSIFICATION*

* Classification adopted from World Health Organization classification.

Adapted from Carter MC, Metcalfe DD: Paediatric mastocytosis, Arch Dis Child 86:315-319, 2002.

Clinical Manifestations

Solitary mastocytomas are 1-5 cm in diameter. Lesions may be present at birth or may arise in early infancy at any site. The lesions may manifest as recurrent, evanescent wheals or bullae; in time, an infiltrated, pink, yellow, or tan, rubbery plaque develops at the site of whealing or blistering (Fig. 651-14). The surface acquires a pebbly, orange peel–like texture, and hyperpigmentation may become prominent. Stroking or trauma to the nodule may lead to urtication (Darier sign) as a result of local histamine release; rarely, systemic signs of histamine release become apparent.

Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of mastocytosis. In the first type of urticaria pigmentosa, the classic infantile type, lesions may be present at birth but more often erupt in crops in the first several months to 2 yr of age. New lesions seldom arise after age 3-4 yr. In some cases, early bullous or urticarial lesions fade, only to recur at the same site, ultimately becoming fixed and hyperpigmented. In others, the initial lesions are hyperpigmented. Vesiculation usually abates by 2 yr of age. Individual lesions range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters and may be macular, papular, or nodular. They range in color from yellow-tan to chocolate brown and often have ill-defined borders (Fig. 651-15). Larger nodular lesions, like mastocytomas, may have a characteristic orange peel texture. Lesions of urticaria pigmentosa may be sparse or numerous and are often symmetrically distributed. Palms, soles, and face are sometimes spared, as are the mucous membranes. The rapid appearance of erythema and whealing in response to vigorous stroking of a lesion can usually be elicited; dermographism of intervening normal skin is also common. Affected children can have intense pruritus. Systemic signs of histamine release, such as hypotension, syncope, headache, episodic flushing, tachycardia, wheezing, colic, and diarrhea, occur most frequently in the more severe types of mastocytosis. Flushing is by far the most common symptom seen.

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis is characterized by diffuse involvement of the skin rather than discrete hyperpigmented lesions. Affected patients are usually normal at birth and demonstrate features of the disorder after the first few months of life. Rarely, the condition may present with intense generalized pruritus in the absence of visible skin changes. The skin usually appears thickened and pink to yellow and may have a doughy feel and a texture resembling an orange peel. Surface changes are accentuated in flexural areas. Recurrent bullae (Fig. 651-16), intractable pruritus, and flushing attacks are common, as is systemic involvement.

Differential Diagnosis

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytoma may be confused with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans must be differential from other causes of telangiectasia.

Treatment

In urticaria pigmentosa, flushing can be precipitated by excessively hot baths, vigorous rubbing of the skin, and certain drugs, such as codeine, aspirin, morphine, atropine, ketorolac, alcohol, tubocurarine, iodine-containing radiographic dyes, and polymyxin B (Table 651-2). Avoidance of these triggering factors is advisable; it is notable that general anesthesia may be safely performed with appropriate precautions.

Table 651-2 PHARMACOLOGIC AGENTS AND PHYSICAL STIMULI THAT MAY EXACERBATE MAST CELL MEDIATOR RELEASE IN PATIENTS WITH MASTOCYTOSIS

IMMUNOLOGIC STIMULI

Venoms (immunoglobulin E–mediated bee venom)

Complement-derived anaphylatoxins

Biologic peptides (substance P, somatostatin)

Polymers (dextran)

NONIMMUNOLOGIC STIMULI

Physical stimuli (extreme temperature, friction, sunlight)

Drugs

Acetylsalicylic acid and related nonsteroidal analgesics*

Thiamine

Ketorolac tromethamine

Alcohol

Narcotics (codeine, morphine)*

Radiographic dyes (iodine containing)

* Appears to be a problem in <10% of patients.

From Carter MC, Metcalfe DD: Paediatric mastocytosis, Arch Dis Child 86:315-319, 2002.

Ahmad N, Evans P, Lloyd-Thomas AB. Anesthesia in children with mastocytosis—a case based review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:97-107.

Beers WH, Once A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

Bergen AA, Plomp AS, Hu X, et al. ABCC6 and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:685-691.

Brooke BS. Celiprolol therapy for vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Lancet. 2010;376:1443-1444.

Chan I, Liu L, Hamida T, et al. The molecular basis of lipoid proteinosis: mutations in extracellular matrix protein 1. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:881-890.

Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

Hodak E, David M. Primary anetoderma and antiphospholipid antibodies—review of the literature. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;32:162-166.

Lee JK, Whittaker SJ, Enns RA, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic mastocytosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7005-7008.

Martin L, Maitre F, Bonicel P, et al. Heterozygosity for a single mutation in the ABCC6 gene may closely mimic PXE. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:301-306.

Metcalfe DD. Mast cells and mastocytosis. Blood. 2008;112:946-956.

Ong KT, Perdu J, De Backer J, et al. Effect of celiprolol on prevention of cardiovascular events in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a prospective randomised, open, blind-endpoints trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1476-1484.

Parapia LA, Jackson C. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome—a historical review. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:32-35.

Schoepe S, Schake H, May E, et al. Glucocorticoid therapy-induced skin atrophy. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:406-420.

Vearrier D, Buka RL, Roberts B, et al. What is the standard of care in the evaluation of elastosis perforans serpiginosa? A survey of pediatric dermatologists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:219-224.

Wolfram D, Tzankov A, Pulzl P, et al. Hypertrophic scars and keloids—a review of their pathophysiology, risk factors, and therapeutic management. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:171-181.