Chapter 25 Discontinuing Cardiopulmonary Bypass

GENERAL PREPARATIONS

Temperature

Because at least moderate hypothermia is used during CPB in most cardiac surgery cases, it is important that the patient is sufficiently rewarmed before attempting to wean from CPB (Table 25-1). Initiation of rewarming is a good time to consider whether additional drugs need to be given to keep the patient anesthetized. Anesthetic vaporizers need to be off for 10 to 20 minutes before coming off CPB to clear the agent from the patient if so desired. Monitoring the temperature of a highly perfused tissue such as the nasopharynx is useful to help prevent overheating the brain during rewarming, but these temperatures may rise more rapidly than others, such as bladder, rectum, or axilla temperatures, leading to inadequate rewarming and temperature dropoff after CPB as the heat continues to distribute throughout the body. Different institutions have various protocols for rewarming, but the important point is to warm gradually, avoiding hyperthermia of the central nervous system while getting enough heat into the patient to prevent significant dropoff after CPB.1 After CPB, there is a tendency for the patient to lose heat, and measures to keep the patient warm such as fluid warmers, a circuit heater-humidifier, and forced-air warmers should be set up and turned on before weaning from CPB. The temperature of the operating room may need to be increased as well; this is probably an effective measure to keep a patient warm after CPB, but it may make the scrubbed and gowned personnel uncomfortable.

Table 25-1 General Preparations for Discontinuing Cardiopulmonary Bypass

| Temperature | Laboratory Results |

|---|---|

| Adequately rewarm before weaning from CPB | Correct metabolic acidosis |

| Avoid overheating the brain | Optimize hematocrit |

| Start measures to keep patient warm after CPB | Normalize K+ |

| Use fluid warmer, forced air warmer | Consider giving Mg2+ or checking Mg2+ level |

| Warm operating room | Check Ca2+ level and correct deficiencies |

Laboratory Results

Arterial blood gas analysis should be obtained before weaning from CPB and any abnormalities corrected. Severe metabolic acidosis depresses the myocardium and should be treated with sodium bicarbonate or tromethamine (Tham). The optimal hematocrit for weaning from CPB is controversial and probably varies from patient to patient.2 It makes sense that sicker patients with lower cardiovascular reserve may benefit from a higher hematocrit, but the risks and adverse consequences of transfusion need to be considered as well. Suffice it to say that the hematocrit should be measured and optimized before weaning from CPB. The serum potassium level should be measured before weaning from CPB and may be high due to cardioplegia or low, especially in patients receiving loop diuretics. Hyperkalemia may make establishing an effective cardiac rhythm difficult and can be treated with sodium bicarbonate, calcium chloride, or insulin, but the levels usually decrease quickly after cardioplegia has been stopped. Low serum potassium levels should probably be corrected before coming off CPB, especially if arrhythmias are present. Administration of magnesium to patients on CPB decreases postoperative arrhythmias and may improve cardiac function, and many centers routinely give all CPB patients magnesium sulfate. Theoretical disadvantages include aggravation of vasodilation and inhibition of platelet function.3,4 If magnesium is not given routinely, the level should be checked before weaning from CPB and deficiencies corrected. The ionized calcium level should be measured, and significant deficiencies corrected before discontinuing CPB. Many centers give all patients a bolus of calcium chloride just before coming off CPB because it transiently increases contractility and systemic vascular resistance. However, it has been argued that this practice is to be avoided because calcium may interfere with catecholamine action and aggravate reperfusion injury.

PREPARING THE LUNGS

As the patient is weaned from CPB and the patient’s heart starts to support the circulation, the lungs again become the site of gas exchange, delivering oxygen and eliminating carbon dioxide. Before weaning from CPB, the lung function must be restored (Table 25-2). The lungs are reinflated by hand gently and gradually, with sighs using up to 30 cmH2O pressure, and then mechanically ventilated with 100% oxygen. Care should be taken not to allow the left lung to injure an in situ internal mammary artery graft as the lung is reinflated. The compliance of the lungs can be judged by their feel with hand ventilation, with stiff lungs suggesting more difficulty with oxygenation or ventilation after CPB. If visible, both lungs should be inspected for residual atelectasis, and they should be rising and falling with each breath. Ventilation alarms and monitors should be activated. If prolonged expiration or wheezing is detected, bronchodilators should be given. The surgeon should inspect both pleural spaces for pneumothorax, which should be treated with chest tubes. Any fluid present in the pleural spaces should be removed before attempting to wean the patient from CPB.

Table 25-2 Preparing the Lungs for Discontinuing Cardiopulmonary Bypass

PREPARING THE HEART

Preparing the heart to resume its function pumping blood involves optimizing the five hemodynamic parameters that can be controlled: rhythm, rate, contractility, afterload, and preload (Table 25-3).

Table 25-3 Preparing the Heart for Discontinuing Cardiopulmonary Bypass

| Parameter | Preparation |

|---|---|

| Rhythm |

AV = atrioventricular; CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass; LV = left ventricular; MAP = mean arterial pressure; MR = mitral regurgitation; RV = right ventricular; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

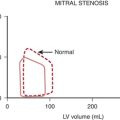

Preload

In the intact heart, the best measure of preload is end-diastolic volume. Less direct clinical measures of preload include left atrial pressure (LAP), pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP), and pulmonary artery diastolic pressure, but there may be a poor relationship between end-diastolic pressure and volume during cardiac surgery. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is a useful tool for weaning from CPB because it provides direct visualization of the end-diastolic volume and contractility of the left ventricle.5 The process of weaning a patient from CPB involves increasing the preload (i.e., filling the heart from its empty state on CPB) until an appropriate end-diastolic volume is achieved. When preparing to discontinue CPB, some thought should be given to the appropriate range of preload for the particular patient. The filling pressures before CPB may indicate what they need to be after CPB; a heart with high filling pressures before CPB may require high filling pressures after CPB to achieve an adequate preload.

FINAL PREPARATIONS

The final preparations before discontinuing CPB include leveling the operating table, re-zeroing the pressure transducers, ensuring the proper function of all monitoring devices, confirming that the patient is receiving only intended drug infusions, ensuring the immediate availability of resuscitation drugs and appropriate fluid volume, and verifying that the lungs are being ventilated with 100% oxygen (Table 25-4).

Table 25-4 Final Preparations for Discontinuing Cardiopulmonary Bypass

| Anesthesiologist’s Preparations | Surgeon’s Preparations |

|---|---|

| Level operating table | Remove macroscopic collections of air from the heart |

| Re-zero transducers | Control major sites of bleeding |

| Activate monitors | CABG lying nicely without kinks |

| Check drug infusions | Cardiac vents off or removed |

| Have resuscitation drugs and fluid volume on hand | Clamps off the heart and great vessels |

| Reestablish TEE/PA catheter monitoring | Tourniquets around caval cannulas loose |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography; PA = pulmonary artery

ROUTINE WEANING FROM CARDIOPULMONARY BYPASS

After discontinuing CPB, the anticoagulation by heparin is reversed with protamine. Depending on institutional preference, protamine may be administered before or after removal of the arterial cannula. Giving it before removal allows for continued transfusion from the pump and easier return to CPB if there is a severe protamine reaction. Giving protamine after removal of the arterial cannula probably decreases the risk of thrombus formation and systemic embolization. After the infusion of protamine is started, pump suction return to the reservoir should be stopped to keep protamine out of the pump circuit in case subsequent return to CPB becomes necessary. Protamine should be given slowly through a peripheral intravenous catheter over 7 to 15 minutes while watching for systemic hypotension and pulmonary hypertension, which may indicate that an untoward (allergic) reaction to protamine is occurring.6 Technically flawed coronary artery bypass grafts may thrombose after protamine administration, causing acute ischemia and mimicking a protamine reaction.

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT OF VENTRICULAR DYSFUNCTION

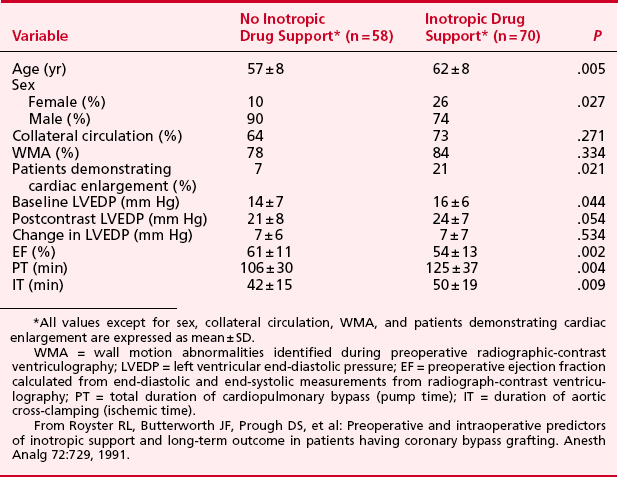

Severe ventricular dysfunction, specifically the low cardiac output syndrome (LCOS), occurring after CPB and cardiac surgery differs from chronic congestive heart failure (CHF) (Box 25-1). Patients emerging from CPB have hemodilution, moderate hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, and altered potassium levels. Depending on temperature and depth of anesthesia, these individuals may demonstrate low, normal, or high SVR. Increasing age, female sex, decreased LV ejection fraction, and increased duration of CPB are associated with a greater likelihood that inotropic support will be needed after CABG surgery (Table 25-5).

The following discussion provides an overview of the pharmacologic approach to management of perioperative ventricular dysfunction in the setting of cardiac surgery. Management goals are described in Table 25-6. These are extensions of the routine preparations made for discontinuing CPB shown in Table 25-3.

| Physiologic Variable | Management |

|---|---|

| Heart rate and rhythm | Maintain normal sinus rhythm, avoid tachycardia; for tachycardia or bradycardia, consider pacing or chronotropic agents (atropine, isoproterenol, epinephrine), correct acid-base disturbances and electrolytes, and review current medications. |

| Preload | Reduce increased preload with diuretics or venodilators (nitroglycerin or sodium nitroprusside); monitor CVP, PCWP, and SV; obtain echocardiogram to rule out ischemia, valvular lesions, tamponade, and intracardiac shunts; consider using inotropes, IABP, or both. |

| Afterload | Avoid increased afterload (increased wall tension); use vasodilators (sodium nitroprusside); avoid hypotension; maintain coronary perfusion pressure; consider IABP, inotropes devoid of α1-adrenergic effects (dobutamine or milrinone), or both IABP and inotropes. |

| Contractility | Assess hemodynamics, rule out ischemia/infarction, assess rate/rhythm, preload, and afterload; use inotropes; if uncertain, obtain echocardiogram to assess cardiac function. Consider combination therapy with inotropes and vasodilators and/or assist devices (IABP/LVAD/RVAD). |

| Oxygen delivery | Increase FiO2 and CO; check ABGs and chest radiograph; mechanical ventilation if indicated; correct acid-base disturbances. |

FiO2 = inspired oxygen concentration; ABGs = arterial blood gas; CO = cardiac output; CVP = central venous pressure; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SV = stroke volume.

Sympathomimetic Amines

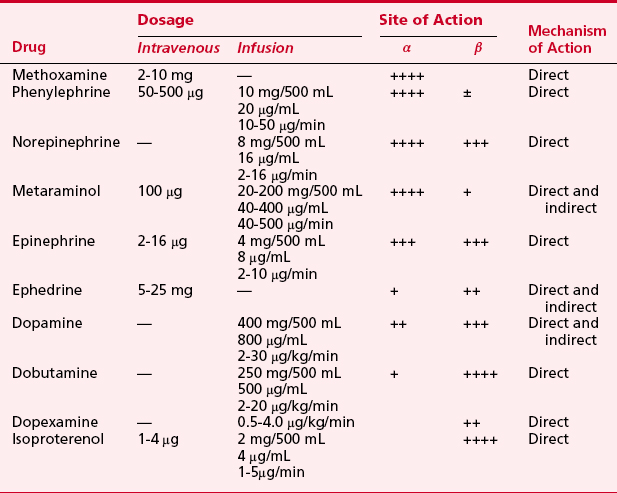

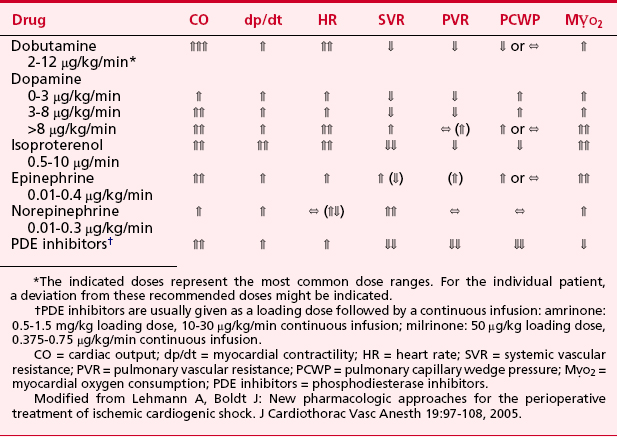

Sympathomimetic drugs (i.e., catecholamines) are pharmacologic agents capable of providing inotropic and vasoactive effects (Box 25-2). Catecholamines exert positive inotropic action by stimulation of the β1-receptor. The predominant hemodynamic effect of a specific catecholamine depends on the degree to which the various α-, β-, and dopaminergic receptors are stimulated (Tables 25-7 and 25-8).

Epinephrine

Epinephrine stimulates α- and β-adrenergic receptors in a dose-dependent fashion. It is frequently the inotrope of choice after CPB (Box 25-3). Doses of 10, 20, and 40 ng/kg/min increased stroke volume by 2%, 12%, and 22%, respectively, and increased cardiac index (CI) by 0.1, 0.7, and 1.2 L/min/m2. The HR also increased, but by no more than 10 beats per minute at any dose. Epinephrine is frequently used after cardiac surgery to support the function of the “stunned” reperfused heart. During emergence from CPB, Butterworth and colleagues showed epinephrine (30 ng/kg/min) increased CI and stroke volume by 14% without increasing HR.7 In cardiac surgical patients, epinephrine infusion (0.01 to 0.4 μg/kg/min) effectively increases cardiac output, minimally increases HR, and has acceptable side effects.

Dobutamine

Dobutamine is a synthetic catecholamine that generally produces dose-dependent increases in cardiac output and reductions in diastolic filling pressures. The effects of epinephrine (30 ng/kg/min) were compared with those of dobutamine (5 μg/kg/min) in 52 patients recovering from CABG surgery.7 Both drugs significantly and similarly increased stroke volume index, but epinephrine increased the HR by only 2 beats per minute whereas dobutamine increased the HR by 16 beats per minute.

In addition to increasing contractility, dobutamine may have favorable metabolic effects on ischemic myocardium. Intravenous and intracoronary injections of dobutamine increase coronary blood flow in animal studies. In paced cardiac surgical patients, dopamine increased oxygen demand without increasing oxygen supply whereas dobutamine increased myocardial oxygen uptake and coronary blood flow. However, because increases in HR are a major determinant of  , these favorable effects of dobutamine could be lost if dobutamine induces tachycardia. During dobutamine stress-echocardiography, segmental wall motion abnormalities suggestive of myocardial ischemia can occur as a result of tachycardia and increases in

, these favorable effects of dobutamine could be lost if dobutamine induces tachycardia. During dobutamine stress-echocardiography, segmental wall motion abnormalities suggestive of myocardial ischemia can occur as a result of tachycardia and increases in  .8

.8

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is used primarily to treat vasodilated patients after CPB. The α-adrenergic agonists benefit certain patients with circulatory failure refractory to inotropic and fluid therapy. Phenylephrine, norepinephrine, or vasopressin may be used to restore MAP in patients with a low SVR after CPB (i.e., vasoplegia syndrome).9 When RV dysfunction primarily is a result of decreased CPP, vasoconstrictors can be used to optimize RV performance.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

The PDE-III inhibitors amrinone (inamrinone) and milrinone increase cyclic adenosine monophosphate, calcium flux, and calcium sensitivity of contractile proteins. These drugs have a similar mode of action because they are noncatecholamine and nonadrenergic agents. They do not rely on β-receptor stimulation for their positive inotropic activity. As a result, the effectiveness of the PDE-III inhibitors is not altered by previous β-blockade nor is it reduced in patients who may experience β-receptor downregulation. In addition to their positive inotropic effects, these agents produce systemic and pulmonary vasodilation. As a result of this combination of hemodynamic effects (i.e., positive inotropic support and vasodilation), the term inodilator has been used to describe these drugs (Box 25-4).

Because these agents exert their hemodynamic effects by a nonadrenergic mechanism of action, when used in combination with β-agonists they have an additive effect on myocardial performance. Investigators have demonstrated the clinical application of combination therapy using PDE-III inhibitors and dopamine, phenylephrine, epinephrine, and nitroglycerin.10

A second-generation PDE-III inhibitor, milrinone has a similar hemodynamic profile to amrinone; however, its positive inotropic action is 15 to 30 times that of amrinone. Thrombocytopenia has been a potential clinical concern with the administration of PDE-III inhibitors, particularly amrinone. However, no significant reduction in platelet count occurred after 48 hours of milrinone infusion in cardiac surgical patients. Intravenous milrinone has been studied extensively and demonstrates a favorable short-term effect in CHF and ventricular dysfunction after CPB.11

The ability of short-term administration of milrinone to augment ventricular performance in patients undergoing cardiac surgery was shown in the results from the European Milrinone Multicentre Trial Group.12 In this prospective study, intravenous milrinone was studied in patients after CPB. All patients received a bolus infusion of milrinone at 50 μg/kg over 10 minutes, followed by a maintenance infusion of 0.375, 0.5, or 0.75 μg/kg/min for 12 hours. Significant increases in stroke volume and CI were observed. In addition, significant decreases in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), CVP, PAP, MAP, and SVR were seen. Eighteen patients (14%) had arrhythmias; most occurred in the group receiving 0.75 μg/kg/min. Two arrhythmic events were deemed serious; both were bouts of rapid atrial fibrillation occurring with the higher dose.

After CPB, a loading dose of milrinone at 50 μg/kg, followed by a continuous infusion of 0.5 μg/kg/min, resulted in a significant increase in cardiac output. Butterworth and colleagues13 also studied the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of milrinone in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery; milrinone (25, 50, or 75 μg/kg) was given if the CI was less than 3.0 L/min/m2 after separation from CPB. All three doses of milrinone significantly increased CI. The 50- and 75-μg/kg doses produced significantly greater increases in CI than the 25-μg/kg dose. The 75-μg/kg dose produced increases in CI comparable with the 50-μg/kg dose, but it was associated with more hypotension, despite administration of intravenous fluid, blood, and a phenylephrine infusion. The initial redistribution half-lives were 4.6, 4.3, and 6.9 minutes, and the terminal elimination half-lives were 63, 82, and 99 minutes for the 25-, 50-, and 75-μg/kg doses, respectively. The results of these investigations suggest that for optimizing hemodynamic performance (while minimizing any potential for arrhythmias), the middle dose range (i.e., loading dose of 50 μg/kg) of milrinone may be most efficacious with a continuous infusion of 0.5 μg/kg/min, leading to a plasma concentration of more than 100 mg/mL. In patients with poor LV function, the loading dose should be given during CPB to avoid a decrease in MAP and to minimize the need for other inotropes on discontinuing CPB.

Vasodilators

The indications for using vasodilators such as nitroglycerin or nitroprusside in cardiac surgery include management of perioperative systemic or pulmonary hypertension, myocardial ischemia, and ventricular dysfunction complicated by excessive pressure or volume overload (Box 25-5). In most conditions, nitroglycerin or nitroprusside may be used. Both share common features such as rapid onset, ultra-short half-lives (several minutes), and easy titratability. Nevertheless, there are important pharmacologic differences between nitroglycerin and nitroprusside. In the setting of ischemia, nitroglycerin is preferred because it selectively vasodilates coronary arteries without producing a coronary “steal.” Likewise, in the management of ventricular volume overload or RV pressure overload, nitroglycerin may offer some advantage over nitroprusside. It has a predominant influence on the venous bed such that preload can be reduced without significantly compromising systemic arterial pressure. The benefits of nitroglycerin are improvement in stroke volume, reduction in wall tension and  , increased perfusion to the subendocardium as a result of a lower LVEDP, and maintenance of CPP. Nitroprusside is a more potent arterial vasodilator and may potentiate myocardial ischemia due to a coronary steal phenomenon or a reduction in coronary perfusion pressure. Its greater potency, however, makes nitroprusside the vasodilator of choice for management of perioperative hypertensive disorders and for afterload reduction during or after surgery for regurgitant valvular lesions.

, increased perfusion to the subendocardium as a result of a lower LVEDP, and maintenance of CPP. Nitroprusside is a more potent arterial vasodilator and may potentiate myocardial ischemia due to a coronary steal phenomenon or a reduction in coronary perfusion pressure. Its greater potency, however, makes nitroprusside the vasodilator of choice for management of perioperative hypertensive disorders and for afterload reduction during or after surgery for regurgitant valvular lesions.

Despite proven benefits of vasodilator therapy in the management of CHF, they can be difficult drugs to use in treatment of perioperative ventricular dysfunction. This is most evident in cases of the LCOS when impaired pump function is complicated by inadequate perfusion pressure. In these situations, multidrug therapy with vasoactive and cardioactive agents is warranted (i.e., nitroglycerin or nitroprusside plus epinephrine or milrinone and norepinephrine). Combination therapy enables greater selectivity of effect. The unwanted side effects of one drug can be avoided while supplementing the desired effects with another agent.14 To maximize the desired effects of any particular combination of agents, frequent assessment of cardiac performance with a pulmonary artery catheter and TEE is needed. This allows the Starling curve and the pressure-volume loops to be visualized as they are shifted up and to the left with therapy.

Additional Pharmacologic Therapy

Following the steps outlined in Tables 25-3 and 25-6, most patients can be weaned off of CPB. However, a small percentage will be difficult to safely remove from CPB because of their chronic end-stage CHF or an acute insult during cardiac surgery producing cardiogenic shock. These patients will probably require mechanical circulatory support. However, while instituting these further steps, some clinicians try additional pharmacologic therapy.

Controversial Older Treatments

The administration of glucose-insulin-potassium or just glucose and insulin has been found to be useful for metabolic support of the heart after CPB. The trauma of cardiac surgery produces insulin resistance, which restricts the availability of carbohydrates to the heart. The increased level of catecholamines during CPB may also put further strain on the energy metabolism of the heart, whereas insulin may improve this situation.15 The administration of high-dose insulin has been compared with dopamine in patients undergoing CABG surgery. The infusion of dopamine (7 μg/kg/min) alone induced metabolic changes unfavorable to the myocardium, whereas dopamine plus insulin increased carbohydrate use with cessation of cardiac uptake of free fatty acids.

New Treatments for Heart Failure and Cardiogenic Shock

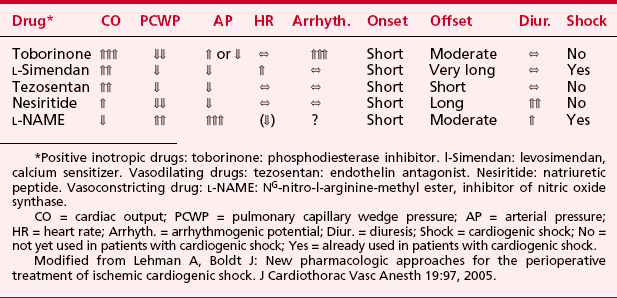

Levosimendan is a new positive inotropic drug belonging to the class of calcium sensitizers. The drug stabilizes the calcium-induced conformational change in cardiac troponin C and prolongs the effective cross-bridging time. In contrast to other positive inotropic drugs, levosimendan does not increase intracellular calcium. The drug has vasodilating and anti-ischemic properties produced by opening K+-ATP channels16 (Table 25-9).

Levosimendan is recommended by the European Society of Cardiology for treatment of acute worsening of heart failure and for acute heart failure after myocardial infarction.17 It has also been found to enhance contractile function of stunned myocardium in patients with acute coronary syndromes. It is available clinically in Europe and is undergoing evaluation in the United States. The use of levosimendan has been reported in cardiac surgical patients with high perioperative risk, compromised LV function, difficulties in weaning from CPB, and severe RV failure after mitral valve replacement. The doses used were 12 μg/kg as a 10-minute loading dose, followed by an infusion of 0.1 μg/kg/min. It has been used preoperatively, during emergence from CPB, and in the postoperative period for up to 28 days. The potential for levosimendan to produce increased contractility, decreased resistance, minimal metabolic cost, and no arrhythmias makes it a potentially useful addition to the treatments for patients with LCOS or RV failure.

Numerous other drugs are being studied for their uses in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and cardiogenic shock. These drugs include positive inotropic agents such as toborinone (a PDE-III inhibitor), vasodilators such as tezosentan (a specific and potent dual endothelin-receptor antagonist), and vasopressors such as L-NAME (a nitric oxide inhibitor) (see Table 25-9). These various drugs may prove useful for certain types of cardiovascular problems in the future.

INTRA-AORTIC BALLOON PUMP COUNTERPULSATION

Indications and Contraindications

Since its introduction, the indications for the IABP have grown (Table 25-10). The most common use of the IABP is for treatment of cardiogenic shock. This may occur after CPB or after cardiac surgery in patients with shock preoperatively with acute postinfarction ventricular septal defects or mitral regurgitation, those who require stabilization before surgery, or patients who decompensate hemodynamically during cardiac catheterization. Patients with myocardial ischemia refractory to coronary vasodilation and afterload reduction are stabilized with an IABP before cardiac catheterization, and some patients with severe CAD will prophylactically have an IABP inserted before undergoing CABG or off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery.18

Table 25-10 Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump Counterpulsation Indications and Contraindications

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

Insertion Techniques

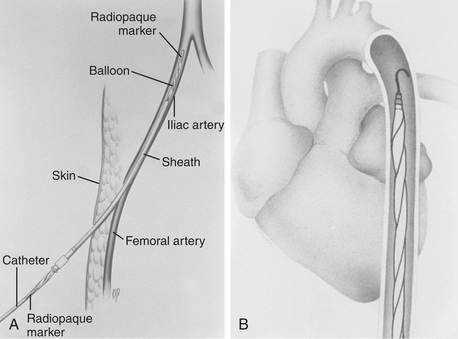

The femoral vessel with the greater pulse is sought by careful palpation. The length of the balloon to be inserted is estimated by laying the balloon tip on the patient’s chest at Louis’ angle and appropriately marking the distal point corresponding to the femoral artery. Care must be taken when removing the balloon from its package to follow the manufacturer’s procedures exactly so as not to cause perforation of the balloon before insertion. Available balloons come wrapped and need only be appropriately deflated before removal from the package. The femoral artery is entered with the supplied needle, a J-tipped guidewire is inserted to the level of the aortic arch, and the needle is removed. The arterial puncture site is enlarged with the successive placement of an 8-Fr dilator and then a 10.5- or 12-Fr dilator and sheath combination (Fig. 25-1). In the adult-sized (30- to 50-mL) balloons, only the dilator needs to be removed, leaving the sheath and guidewire in the artery. The balloon is threaded over the guidewire into the central aorta and into the previously estimated correct position in the proximal segment of the descending aorta. The sheath is gently pulled back to connect with the leakproof cuff on the balloon hub, ideally so that the entire sheath is out of the arterial lumen to minimize risk of ischemic complications to the distal extremity. Alternatively, the sheath may be stripped off the balloon shaft much like a peel-away pacemaker lead introducer, thereby entirely removing the sheath from the insertion site. At least one manufacturer offers a “sheathless” balloon for insertion.

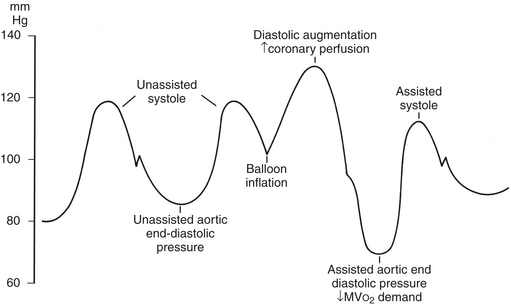

If fluoroscopy is available during the procedure, correct placement is verified before fixing the balloon securely to the skin. Position may also be checked by radiography or echocardiography after insertion. If an indwelling left radial arterial catheter is functioning at the time of insertion, a reasonable estimate of position may be made by watching balloon-mediated alteration of the arterial pulse waveform (Fig. 25-2). After appropriate positioning and timing of the balloon, 1:1 counterpulsation may be initiated. The entire external balloon assembly should be covered in sterile dressings.

Timing and Weaning

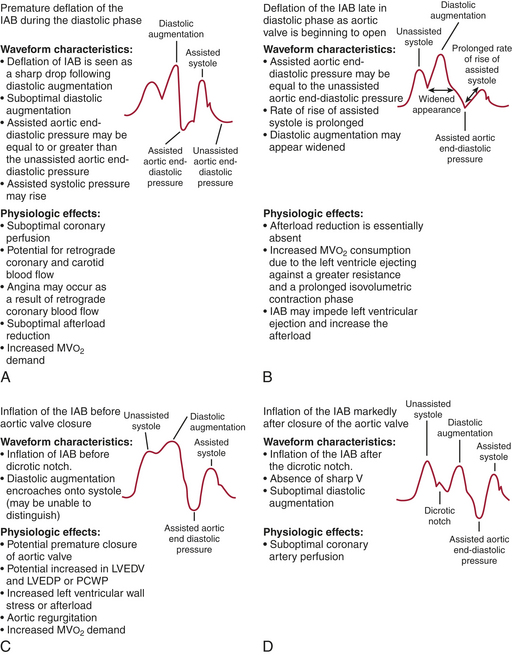

For optimal effect of the IABP, inflation and deflation need to be correctly timed to the cardiac cycle. Although a number of variables, including positioning of the balloon within the aorta, balloon volume, and the patient’s cardiac rhythm, can affect the performance of the IABP, basic principles regarding the function of the balloon must be followed. Balloon inflation should be timed to coincide with aortic valve closure, or aortic insufficiency and LV strain will result. Similarly, late inflation will result in a diminished perfusion pressure to the coronary arteries. Early deflation will cause inappropriate loss of afterload reduction, and late deflation will increase LV work by causing increased afterload, if only transiently. These errors and correct timing diagrams are illustrated in Figures 25-2 and 25-3.

Complications

Several complications have been associated with IABP use (Table 25-11). The most frequently seen complications are vascular injuries, balloon malfunction, and infection.19,20

Table 25-11 Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump Counterpulsation Complications

| Vascular | Miscellaneous | Balloon |

|---|---|---|

SUMMARY

1. Grigore A.M., Grocott H.P., Mathew J.P., et al. Neurologic Outcome Research Group of the Duke Heart Center. The rewarming rate and increased peak temperature alter neurocognitive outcome after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:4.

2. Spiess B.D. Blood transfusion for cardiopulmonary bypass: The need to answer a basic question. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:535.

3. Boyd W.C., Thomas S.J. Pro: Magnesium should be administered to all coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:339.

4. Grigore A.M., Mathew J.P. Con: Magnesium should not be administered to all coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:344.

5. Cheung A.T., Savino J.S., Weiss S.J., et al. Echocardiographic and hemodynamic indexes of left ventricular preload in patients with normal and abnormal ventricular function. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:376.

6. Park K.W. Protamine and protamine reactions. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2004;42:135.

7. Butterworth J.F.4th, Prielipp R.C., Royster R.L., et al. Dobutamine increases heart rate more than epinephrine in patients recovering from aortocoronary bypass surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1992;6:535.

8. Kertai M.D., Poldermans D. The utility of dobutamine stress echocardiography for perioperative and long-term cardiac risk assessment. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19:520.

9. Kristof A.S., Magder S. Low systemic vascular resistance state in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1121.

10. Royster R.L., Butterworth J.F.4th, Prielipp R.C., et al. Combined inotropic effects of amrinone and epinephrine after cardiopulmonary bypass in humans. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:662.

11. Levy J.H., Bailey J.M., Deeb J.M. Intravenous milrinone in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:325.

12. Feneck R.O. Intravenous milrinone following cardiac surgery: I. Effects of bolus infusion followed by variable dose maintenance infusion. The European Milrinone Multicentre Trial Group. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1992;6:554.

13. Butterworth J.F.4th, Hines R.L., Royster R.L., James R.L. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of milrinone in adults undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:783.

14. Felker J.M. Inotropic therapy for heart failure: An evidence-based approach. Am Heart J. 2001;142:393.

15. Wallin M., Barr G., Owall A., et al. The influence of glucose-insulin-potassium on GH/IGF-1/IGFBP-1 axis during elective coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:470.

16. Lehmann A., Boldt J. New pharmacologic approaches for the perioperative treatment of ischemic cardiogenic shock. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19:97.

17. Remme W., Swedberg K., the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1527.

18. Stone G., Ohman E., Miller M., et al. Contemporary utilization and outcomes of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in acute myocardial infarction: The Benchmark Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1940.

19. Craver J., Murrah C. Elective intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation for high-risk off-pump coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1220.

20. Ferguson J., Cohen M., Freedan R., et al. The current practice of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation: Results from the Benchmark Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1456.

) gives an indication of the adequacy of peripheral perfusion during CPB. If the is greater than 60%, oxygen delivery during CPB is adequate; if it is less than 50%, oxygen delivery is inadequate, and measures to improve delivery (e.g., increase pump flow or hematocrit) or decrease consumption (e.g., give more anesthetic agents or neuromuscular blocking drugs) need to be taken before coming off CPB. An between 50% and 60% is marginal and must be followed closely. As the patient is weaned from CPB, a rising

) gives an indication of the adequacy of peripheral perfusion during CPB. If the is greater than 60%, oxygen delivery during CPB is adequate; if it is less than 50%, oxygen delivery is inadequate, and measures to improve delivery (e.g., increase pump flow or hematocrit) or decrease consumption (e.g., give more anesthetic agents or neuromuscular blocking drugs) need to be taken before coming off CPB. An between 50% and 60% is marginal and must be followed closely. As the patient is weaned from CPB, a rising  suggests that the net flow to the body is increasing and that the heart and lungs will support the circulation; a falling

suggests that the net flow to the body is increasing and that the heart and lungs will support the circulation; a falling  indicates that tissue perfusion is decreasing and that further intervention to improve cardiac performance will be needed before coming off CPB.

indicates that tissue perfusion is decreasing and that further intervention to improve cardiac performance will be needed before coming off CPB. . It is typically easy to see the right-sided heart volume and function directly in the surgical field and the left side of the heart with TEE, and combining the two observations is a useful approach for weaning from CPB. Overfilling and distention of the heart should be avoided because it may stretch the myofibrils beyond the most efficient length and dilate the annuli of the mitral and tricuspid valves, rendering them incompetent, which is easily detected with TEE. If the patient has two venous cannulae, the smaller of the two may be removed when the pump flow is one half of the full flow rate to improve movement of blood from the great veins into the right atrium. When the pump flow has been decreased to 1 L/min or less in an adult and the hemodynamics are satisfactory, the venous cannula may be completely clamped and the pump flow turned off. At this point, the patient is “off bypass.”

. It is typically easy to see the right-sided heart volume and function directly in the surgical field and the left side of the heart with TEE, and combining the two observations is a useful approach for weaning from CPB. Overfilling and distention of the heart should be avoided because it may stretch the myofibrils beyond the most efficient length and dilate the annuli of the mitral and tricuspid valves, rendering them incompetent, which is easily detected with TEE. If the patient has two venous cannulae, the smaller of the two may be removed when the pump flow is one half of the full flow rate to improve movement of blood from the great veins into the right atrium. When the pump flow has been decreased to 1 L/min or less in an adult and the hemodynamics are satisfactory, the venous cannula may be completely clamped and the pump flow turned off. At this point, the patient is “off bypass.”

) and reduce coronary perfusion pressure (CPP). However, if the factor most responsible for decreased cardiac function is hypotension with concomitantly reduced CPP, use of an α-adrenergic agonist can increase blood pressure and improve diastolic coronary perfusion.

) and reduce coronary perfusion pressure (CPP). However, if the factor most responsible for decreased cardiac function is hypotension with concomitantly reduced CPP, use of an α-adrenergic agonist can increase blood pressure and improve diastolic coronary perfusion. . Data also suggest that milrinone may improve myocardial diastolic relaxation (i.e., positive “lusitropic” effect) and augment coronary perfusion. The proposed mechanism for this effect on diastolic performance is that by decreasing LV wall tension, ventricular filling is enhanced and myocardial blood flow and oxygen delivery are optimized.

. Data also suggest that milrinone may improve myocardial diastolic relaxation (i.e., positive “lusitropic” effect) and augment coronary perfusion. The proposed mechanism for this effect on diastolic performance is that by decreasing LV wall tension, ventricular filling is enhanced and myocardial blood flow and oxygen delivery are optimized.