Chapter 14 DIARRHEA, CHRONIC

Causes of Chronic Diarrhea

Acquired monosaccharide malabsorption

Chronic constipation with overflow diarrhea

Chronic nonspecific diarrhea of childhood

Congenital chloride-losing diarrhea

Eosinophilic gastroenteropathy

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

Weight, height, and head circumference

Weight, height, and head circumference

General examination for evidence of dehydration

General examination for evidence of dehydration

Head and neck examination for nasal polyps or iritis

Head and neck examination for nasal polyps or iritis

Abdominal examination for bowel sounds, distension, tenderness

Abdominal examination for bowel sounds, distension, tenderness

Rectal examination for prolapse, fissure, fistula, or abscess

Rectal examination for prolapse, fissure, fistula, or abscess

Extremity examination for digital clubbing, arthritis, tremor, or edema

Extremity examination for digital clubbing, arthritis, tremor, or edema

Skin examination for eczematous dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema nodosum, or pyoderma gangrenosum

Skin examination for eczematous dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema nodosum, or pyoderma gangrenosum

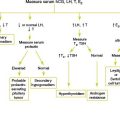

Suggested Work-up

| pH and reducing substances | The presence of reducing substances with a pH less than 6 suggests carbohydrate malabsorption |

| Occult blood | To evaluate for bleeding |

| Fatty acid crystals | Suggests a mucosal problem such as celiac disease |

| Fat globules | The presence of fat globules in an older child suggests steatorrhea but may be normal in the first few months of life |

| Microscopic exam for red blood cells (RBCs) and white blood cells (WBCs) | Neutrophils and RBCs may suggest infection or inflammatory bowel disease |

| Eosinophils suggest parasitic infestation or protein intolerance | |

| Microscopic exam for ova and parasites | To evaluate for parasite infection |

| Stool culture | To evaluate for infectious etiologies |

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) | To evaluate for infection, neutropenia, or eosinophilia. May also reveal microcytic or macrocytic anemia. |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | To evaluate for infection or inflammatory bowel disease |

| Serum electrolytes | To evaluate for electrolyte disturbance |

| Serum protein and albumin levels | To evaluate for malnutrition (proportional decrease) or protein-losing enteropathy (greater loss of albumin) |

| Serum carotene level | To evaluate for fat malabsorption |

Additional Work-up

| Endomysial and tissue transglutaminase antibodies | If celiac disease is suspected |

| Giardia stool antigen | If giardiasis is suspected |

| Serum immunoglobulins | If immunodeficiency is suspected |

| HIV test | If HIV infection is suspected |

| Hydrogen breath test | If carbohydrate malabsorption is suspected |

| 72-hour fecal fat test | If fat malabsorption is suspected |

| Sweat chloride test | If cystic fibrosis is suspected |

| Upper GI series with small-bowel follow-through | If Crohn’s disease or anatomic abnormalities are suspected |

| Barium enema | If Hirschsprung’s disease or inflammatory bowel disease is suspected |

| Sigmoidoscopy | If inflammatory bowel disease or pseudomembranous colitis is suspected |

| Jejunal biopsy | To confirm the presence of celiac disease |

1. Branski D., Lerner A., Lebenthal E. Chronic diarrhea and malabsorption. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:307–328.

2. Fasano A. Clinical presentation of celiac disease in the pediatric population. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S68-S73.

3. Hyman P.E., Milla P.J., Benninga M.A., Davidson G.P., Fleisher D.F., Taminiav J., et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519–1526.

4. Kneepkens C.M.F., Hoekstra J.H. Chronic nonspecific diarrhea of childhood: pathophysiology and management. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:375–390.

5. Leung A.K.C., Robson W.L.M. Evaluating the child with chronic diarrhea. Am Fam Physician. 1996;53:635–643.