Diaper Area Eruptions

Alfons L. Krol, Bernice R. Krafchik

Introduction

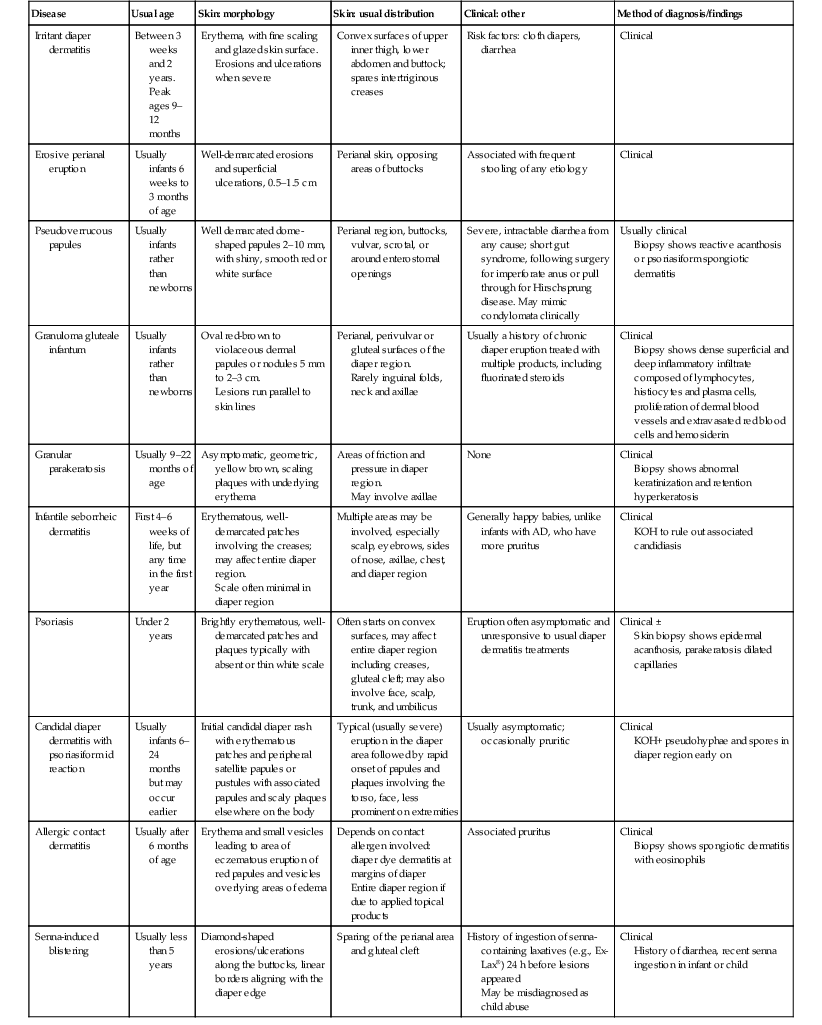

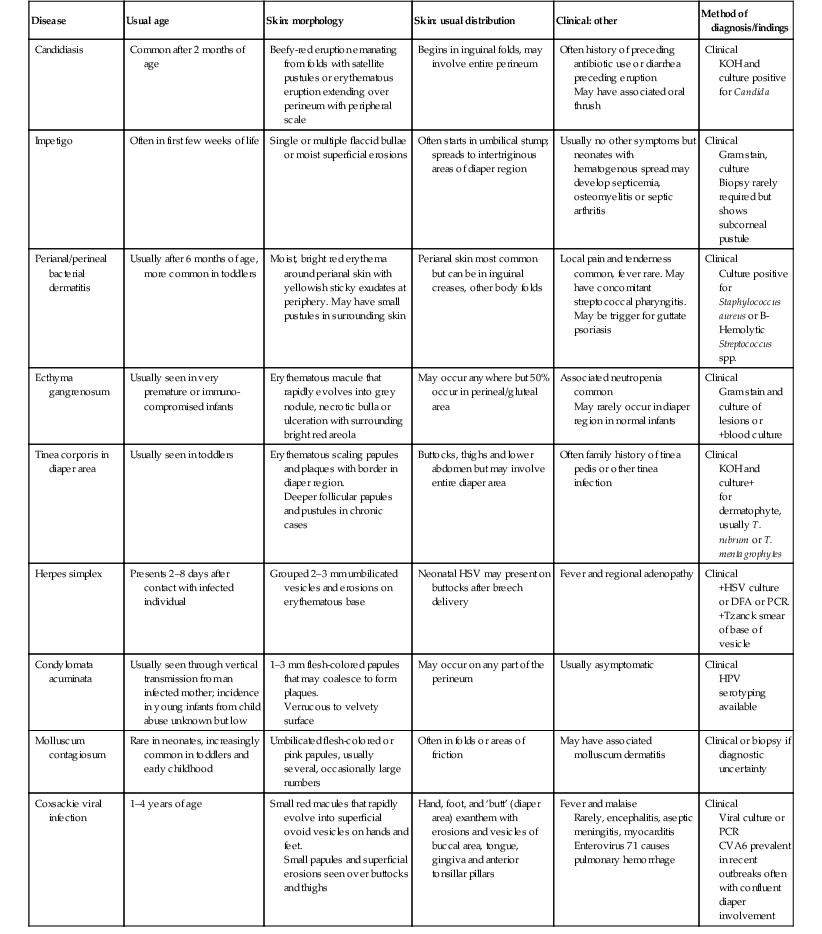

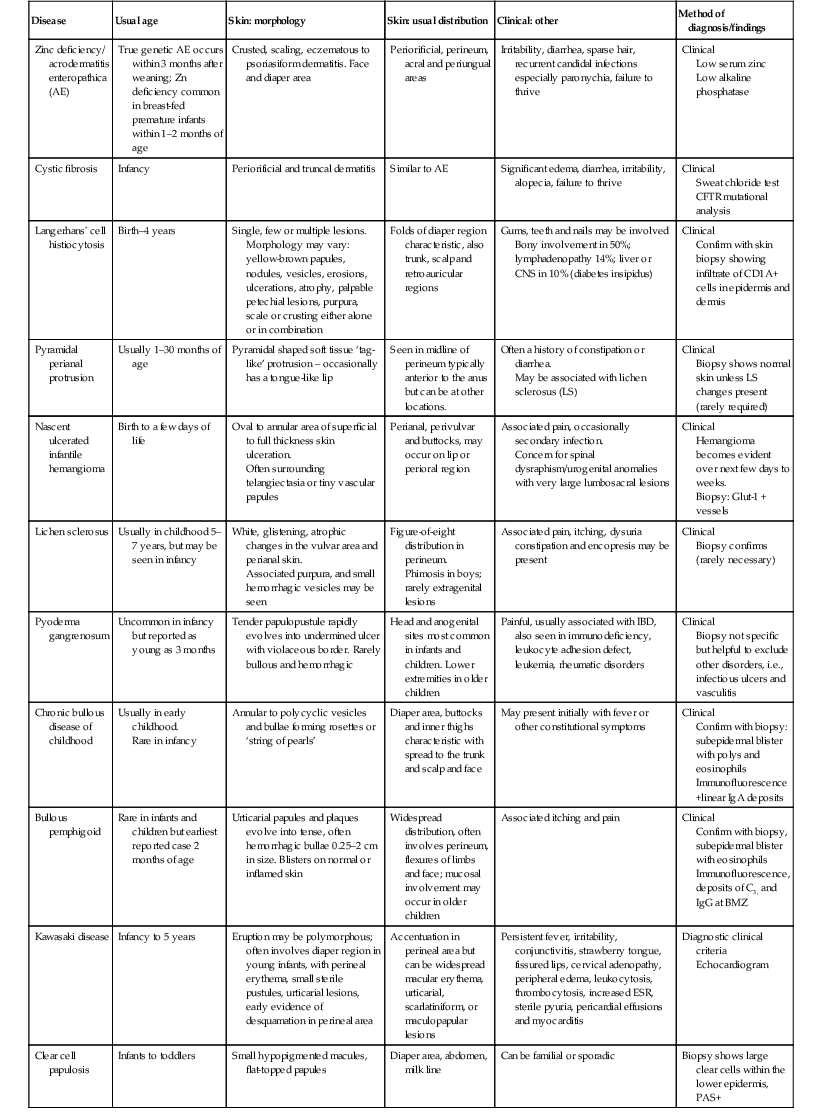

Eruptions in the diaper region have diverse origins. This chapter will review eruptions, both common and uncommon, that have major findings in the diaper area not only in neonates but also in young infants (Box 17.1). Many of the conditions listed in Chapter 10 (vesicles, pustules, bullae, erosions, and ulcerations) may be seen or arise in the diaper region. There are diseases that may also involve other areas of the body and coincidentally affect the diaper area that are mentioned but not discussed in detail in this chapter. Tables 17.1–17.3 describe the clinical setting, morphology, distribution, and best method for diagnosing the major conditions causing diaper area eruptions in neonates and infants.

TABLE 17.1

Eruptions where the diaper/diaper environment is a central cause

| Disease | Usual age | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Method of diagnosis/findings |

| Irritant diaper dermatitis | Between 3 weeks and 2 years. Peak ages 9–12 months | Erythema, with fine scaling and glazed skin surface. Erosions and ulcerations when severe | Convex surfaces of upper inner thigh, lower abdomen and buttock; spares intertriginous creases | Risk factors: cloth diapers, diarrhea | Clinical |

| Erosive perianal eruption | Usually infants 6 weeks to 3 months of age | Well-demarcated erosions and superficial ulcerations, 0.5–1.5 cm | Perianal skin, opposing areas of buttocks | Associated with frequent stooling of any etiology | Clinical |

| Pseudoverrucous papules | Usually infants rather than newborns | Well demarcated dome-shaped papules 2–10 mm, with shiny, smooth red or white surface | Perianal region, buttocks, vulvar, scrotal, or around enterostomal openings | Severe, intractable diarrhea from any cause; short gut syndrome, following surgery for imperforate anus or pull through for Hirschsprung disease. May mimic condylomata clinically | Usually clinical Biopsy shows reactive acanthosis or psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis |

| Granuloma gluteale infantum | Usually infants rather than newborns | Oval red-brown to violaceous dermal papules or nodules 5 mm to 2–3 cm. Lesions run parallel to skin lines |

Perianal, perivulvar or gluteal surfaces of the diaper region. Rarely inguinal folds, neck and axillae |

Usually a history of chronic diaper eruption treated with multiple products, including fluorinated steroids | Clinical Biopsy shows dense superficial and deep inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells, proliferation of dermal blood vessels and extravasated red blood cells and hemosiderin |

| Granular parakeratosis | Usually 9–22 months of age | Asymptomatic, geometric, yellow brown, scaling plaques with underlying erythema | Areas of friction and pressure in diaper region. May involve axillae |

None | Clinical Biopsy shows abnormal keratinization and retention hyperkeratosis |

| Infantile seborrheic dermatitis | First 4–6 weeks of life, but any time in the first year | Erythematous, well-demarcated patches involving the creases; may affect entire diaper region. Scale often minimal in diaper region |

Multiple areas may be involved, especially scalp, eyebrows, sides of nose, axillae, chest, and diaper region | Generally happy babies, unlike infants with AD, who have more pruritus | Clinical KOH to rule out associated candidiasis |

| Psoriasis | Under 2 years | Brightly erythematous, well-demarcated patches and plaques typically with absent or thin white scale | Often starts on convex surfaces, may affect entire diaper region including creases, gluteal cleft; may also involve face, scalp, trunk, and umbilicus | Eruption often asymptomatic and unresponsive to usual diaper dermatitis treatments | Clinical ± Skin biopsy shows epidermal acanthosis, parakeratosis dilated capillaries |

| Candidal diaper dermatitis with psoriasiform id reaction | Usually infants 6–24 months but may occur earlier | Initial candidal diaper rash with erythematous patches and peripheral satellite papules or pustules with associated papules and scaly plaques elsewhere on the body | Typical (usually severe) eruption in the diaper area followed by rapid onset of papules and plaques involving the torso, face, less prominent on extremities | Usually asymptomatic; occasionally pruritic | Clinical KOH+ pseudohyphae and spores in diaper region early on |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | Usually after 6 months of age | Erythema and small vesicles leading to area of eczematous eruption of red papules and vesicles overlying areas of edema | Depends on contact allergen involved: diaper dye dermatitis at margins of diaper Entire diaper region if due to applied topical products |

Associated pruritus | Clinical Biopsy shows spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils |

| Senna-induced blistering | Usually less than 5 years | Diamond-shaped erosions/ulcerations along the buttocks, linear borders aligning with the diaper edge | Sparing of the perianal area and gluteal cleft | History of ingestion of senna-containing laxatives (e.g., Ex-Lax®) 24 h before lesions appeared May be misdiagnosed as child abuse |

Clinical History of diarrhea, recent senna ingestion in infant or child |

TABLE 17.2

Infectious causes of diaper area eruptions

| Disease | Usual age | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Method of diagnosis/findings |

| Candidiasis | Common after 2 months of age | Beefy-red eruption emanating from folds with satellite pustules or erythematous eruption extending over perineum with peripheral scale | Begins in inguinal folds, may involve entire perineum | Often history of preceding antibiotic use or diarrhea preceding eruption May have associated oral thrush |

Clinical KOH and culture positive for Candida |

| Impetigo | Often in first few weeks of life | Single or multiple flaccid bullae or moist superficial erosions | Often starts in umbilical stump; spreads to intertriginous areas of diaper region | Usually no other symptoms but neonates with hematogenous spread may develop septicemia, osteomyelitis or septic arthritis | Clinical Gram stain, culture Biopsy rarely required but shows subcorneal pustule |

| Perianal/perineal bacterial dermatitis | Usually after 6 months of age, more common in toddlers | Moist, bright red erythema around perianal skin with yellowish sticky exudates at periphery. May have small pustules in surrounding skin | Perianal skin most common but can be in inguinal creases, other body folds | Local pain and tenderness common, fever rare. May have concomitant streptococcal pharyngitis. May be trigger for guttate psoriasis | Clinical Culture positive for Staphylococcus aureus or Β-Hemolytic Streptococcus spp. |

| Ecthyma gangrenosum | Usually seen in very premature or immuno-compromised infants | Erythematous macule that rapidly evolves into grey nodule, necrotic bulla or ulceration with surrounding bright red areola | May occur anywhere but 50% occur in perineal/gluteal area | Associated neutropenia common May rarely occur in diaper region in normal infants |

Clinical Gram stain and culture of lesions or +blood culture |

| Tinea corporis in diaper area | Usually seen in toddlers | Erythematous scaling papules and plaques with border in diaper region. Deeper follicular papules and pustules in chronic cases |

Buttocks, thighs and lower abdomen but may involve entire diaper area | Often family history of tinea pedis or other tinea infection | Clinical KOH and culture+ for dermatophyte, usually T. rubrum or T. mentagrophytes |

| Herpes simplex | Presents 2–8 days after contact with infected individual | Grouped 2–3 mm umbilicated vesicles and erosions on erythematous base | Neonatal HSV may present on buttocks after breech delivery | Fever and regional adenopathy | Clinical +HSV culture or DFA or PCR. +Tzanck smear of base of vesicle |

| Condylomata acuminata | Usually seen through vertical transmission from an infected mother; incidence in young infants from child abuse unknown but low | 1–3 mm flesh-colored papules that may coalesce to form plaques. Verrucous to velvety surface |

May occur on any part of the perineum | Usually asymptomatic | Clinical HPV serotyping available |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Rare in neonates, increasingly common in toddlers and early childhood | Umbilicated flesh-colored or pink papules, usually several, occasionally large numbers | Often in folds or areas of friction | May have associated molluscum dermatitis | Clinical or biopsy if diagnostic uncertainty |

| Coxsackie viral infection | 1–4 years of age | Small red macules that rapidly evolve into superficial ovoid vesicles on hands and feet. Small papules and superficial erosions seen over buttocks and thighs |

Hand, foot, and ‘butt’ (diaper area) exanthem with erosions and vesicles of buccal area, tongue, gingiva and anterior tonsillar pillars | Fever and malaise Rarely, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, myocarditis Enterovirus 71 causes pulmonary hemorrhage |

Clinical Viral culture or PCR CVA6 prevalent in recent outbreaks often with confluent diaper involvement |

TABLE 17.3

Eruptions with accentuation in diaper area irrespective of presence of diapers/diaper environment

| Disease | Usual age | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Method of diagnosis/findings |

| Zinc deficiency/ acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) | True genetic AE occurs within 3 months after weaning; Zn deficiency common in breast-fed premature infants within 1–2 months of age | Crusted, scaling, eczematous to psoriasiform dermatitis. Face and diaper area | Periorificial, perineum, acral and periungual areas | Irritability, diarrhea, sparse hair, recurrent candidal infections especially paronychia, failure to thrive | Clinical Low serum zinc Low alkaline phosphatase |

| Cystic fibrosis | Infancy | Periorificial and truncal dermatitis | Similar to AE | Significant edema, diarrhea, irritability, alopecia, failure to thrive | Clinical Sweat chloride test CFTR mutational analysis |

| Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis | Birth–4 years | Single, few or multiple lesions. Morphology may vary: yellow-brown papules, nodules, vesicles, erosions, ulcerations, atrophy, palpable petechial lesions, purpura, scale or crusting either alone or in combination |

Folds of diaper region characteristic, also trunk, scalp and retroauricular regions | Gums, teeth and nails may be involved Bony involvement in 50%; lymphadenopathy 14%; liver or CNS in 10% (diabetes insipidus) |

Clinical Confirm with skin biopsy showing infiltrate of CD1A+ cells in epidermis and dermis |

| Pyramidal perianal protrusion | Usually 1–30 months of age | Pyramidal shaped soft tissue ‘tag-like’ protrusion – occasionally has a tongue-like lip | Seen in midline of perineum typically anterior to the anus but can be at other locations. | Often a history of constipation or diarrhea. May be associated with lichen sclerosus (LS) |

Clinical Biopsy shows normal skin unless LS changes present (rarely required) |

| Nascent ulcerated infantile hemangioma | Birth to a few days of life | Oval to annular area of superficial to full thickness skin ulceration. Often surrounding telangiectasia or tiny vascular papules |

Perianal, perivulvar and buttocks, may occur on lip or perioral region | Associated pain, occasionally secondary infection. Concern for spinal dysraphism/urogenital anomalies with very large lumbosacral lesions |

Clinical Hemangioma becomes evident over next few days to weeks. Biopsy: Glut-1 + vessels |

| Lichen sclerosus | Usually in childhood 5–7 years, but may be seen in infancy | White, glistening, atrophic changes in the vulvar area and perianal skin. Associated purpura, and small hemorrhagic vesicles may be seen |

Figure-of-eight distribution in perineum. Phimosis in boys; rarely extragenital lesions |

Associated pain, itching, dysuria constipation and encopresis may be present | Clinical Biopsy confirms (rarely necessary) |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Uncommon in infancy but reported as young as 3 months | Tender papulopustule rapidly evolves into undermined ulcer with violaceous border. Rarely bullous and hemorrhagic | Head and anogenital sites most common in infants and children. Lower extremities in older children | Painful, usually associated with IBD, also seen in immunodeficiency, leukocyte adhesion defect, leukemia, rheumatic disorders | Clinical Biopsy not specific but helpful to exclude other disorders, i.e., infectious ulcers and vasculitis |

| Chronic bullous disease of childhood | Usually in early childhood. Rare in infancy |

Annular to polycyclic vesicles and bullae forming rosettes or ‘string of pearls’ | Diaper area, buttocks and inner thighs characteristic with spread to the trunk and scalp and face | May present initially with fever or other constitutional symptoms | Clinical Confirm with biopsy: subepidermal blister with polys and eosinophils Immunofluorescence +linear IgA deposits |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Rare in infants and children but earliest reported case 2 months of age | Urticarial papules and plaques evolve into tense, often hemorrhagic bullae 0.25–2 cm in size. Blisters on normal or inflamed skin | Widespread distribution, often involves perineum, flexures of limbs and face; mucosal involvement may occur in older children | Associated itching and pain | Clinical Confirm with biopsy, subepidermal blister with eosinophils Immunofluorescence, deposits of C3, and IgG at BMZ |

| Kawasaki disease | Infancy to 5 years | Eruption may be polymorphous; often involves diaper region in young infants, with perineal erythema, small sterile pustules, urticarial lesions, early evidence of desquamation in perineal area | Accentuation in perineal area but can be widespread macular erythema, urticarial, scarlatiniform, or maculopapular lesions | Persistent fever, irritability, conjunctivitis, strawberry tongue, fissured lips, cervical adenopathy, peripheral edema, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, increased ESR, sterile pyuria, pericardial effusions and myocarditis | Diagnostic clinical criteria Echocardiogram |

| Clear cell papulosis | Infants to toddlers | Small hypopigmented macules, flat-topped papules | Diaper area, abdomen, milk line | Can be familial or sporadic | Biopsy shows large clear cells within the lower epidermis, PAS+ |

The term ‘diaper rash’ refers to any eruption in the area covered by the diaper. There are eruptions that are directly related to the wearing of diapers; those aggravated by wearing diapers; and those that occur in the diaper region, irrespective of whether diapers are worn or not. The majority of severe eruptions which have been a direct consequence of diapering, are more uncommon in countries where disposable diapers are used. Ethnic and cultural differences related to the practice of diapering newborn infants have evolved over hundreds of years, from swaddling in the middle ages to the high-technology, multilayered disposable diapers of the twenty-first century. These latter practices have led to a marked reduction in the frequency of diaper eruptions, particularly irritant diaper dermatitis (IDD).

Care of the diaper area in the newborn

The diaper area in newborns is exposed to urine and feces and it is a combination of both that causes IDD. Normal care of the perineal area should be aimed at gentle removal of the excreta, frequent change of diapers, and use of a mild emollient (petrolatum) to prevent irritation. Infants should be bathed with a mild soap. In preterm infants or those with a tendency to develop irritant diaper dermatitis, a barrier product should be applied to the diaper area with each diaper change. A study integrating these practices into skin care routines for infants in a neonatal intensive care unit has led to significant improvements, with less dryness, redness, and skin surface damage.1 Feces should be removed from the skin as soon as possible after soiling. Plain water alone or a very mild soap, with gentle use of a moist cotton washcloth, is sufficient to remove the feces and urine before the area is gently dried. Rubbing should be avoided. Fragrance- and alcohol-free baby wipes are another convenient option. Baby wipes are now universally alcohol free and contain 98% water.

The ideal or perfect barrier product has yet to be formulated. Traditionally, both lipophilic and hydrophilic ointments and pastes have been used, often combined with zinc oxide. The more lipophilic products may be highly occlusive, whereas the hydrophilic products are more hydrating but function less effectively as a barrier. Pastes such as zinc oxide paste USP (25% zinc oxide, 25% corn starch, 50% petrolatum) are a more effective barrier, but are more adherent and difficult to remove – caregivers may inadvertently irritate the infant’s skin when trying to remove the residual feces and barrier cream. In general, water-in-oil formulations with a lipid content of 50% provide a better barrier than lighter oil-in-water products. Plain petrolatum is recommended for routine use. Soft zinc paste products such as Ihle’s Paste® (Rougier Pharma Canada) or Triple Paste® (Summers Labs, Collegeville, PA) contain a combination of ingredients such as zinc oxide, cornstarch, petrolatum and lanolin, and are excellent, affordable, nonsensitizing products for both prevention and treatment of IDD. Chapter 5 discusses many of the common ingredients in commercial diaper rash products. Talcum or baby powders and products containing boric acid should not be used because of inherent or potential toxicities associated with their use.

Diaper-related eruptions

Irritant diaper dermatitis

Jacquet2 gave the first description of diaper dermatitis in 1905. Irritant diaper dermatitis (IDD) does not usually develop during the neonatal period, particularly in the first 3 weeks of life, and eruptions in the diaper area in this age group should be assumed to be due to causes other than irritation until proven otherwise. Onset of IDD is generally between 3 weeks and 2 years of age, with prevalence highest between 9 and 12 months.3 The condition was previously common, affecting 25% of children seen in a clinic for dermatological diseases,4 but the incidence has decreased remarkably in Western cultures owing to the advent of disposable diapers. In certain societies, such as China, where diapering has not been a social convention, IDD has been distinctly uncommon until recently, with the adoption of Western diapering practices.

Home laundering of diapers is now uncommon in Western societies: most parents in developed countries diaper their infants with disposable or cloth diapers from a diaper service. Modern superabsorbent disposable diapers have been shown to be more effective than washable cloth diapers in reducing IDD,3,5,6 yet it is estimated that 1–2% of the non-biodegradable waste in North American landfills is composed of disposable diapers.

The evolution of disposable diapers from paper to absorbent cellulose centers, to present-day disposables, which contain both an intricate wicking system that prevents backflow and an absorbent gel matrix that can hold 80 times its weight of fluid, has reduced the prevalence of IDD. The most recent advances in disposable diapers include a slow-release petrolatum surface and a breathable outer sheet.

The most important factor in preventing IDD is the frequency and number of diaper changes. Other factors causing IDD include episodes of diarrhea, antibiotic use, and anatomical problems such as short bowel syndrome. Whereas cloth diapers are less efficient at reducing skin wetness, friction and pH, there is a risk that the expense of superabsorbable diapers may prevent parents from changing the diaper sufficiently often, thus contributing to the development of IDD.

Cutaneous findings

IDD presents as erythema on the convex surfaces of the inner upper thigh, the lower abdomen, and buttock areas, the areas most in contact with the diaper. The creases and the suprapubic area in boys are spared (Fig. 17.1). The eruption may become more severe and inflammatory, with yeast colonization, and enlarging areas of involvement, including the creases. In more severe cases, the erythema may be accompanied by a glistening or glazed appearance and a wrinkled surface.

Jacquet’s erosive dermatitis presents with well-demarcated punched-out ulcers and erosions (Fig. 17.2A,B![]() ). It is seen less commonly with the use of disposable diapers, and has usually been associated with infrequent diaper changes and poor removal of chemicals used in home laundering. It may also be seen in infants who have short bowel syndrome or following surgery for Hirschsprung disease, which may result in chronic diarrhea.

). It is seen less commonly with the use of disposable diapers, and has usually been associated with infrequent diaper changes and poor removal of chemicals used in home laundering. It may also be seen in infants who have short bowel syndrome or following surgery for Hirschsprung disease, which may result in chronic diarrhea.

Etiology and pathogenesis

At birth, a newborn’s skin undergoes a sudden transition accompanied by drying and cooling of the skin surface as it adapts to its new environment.7 Visscher8 has measured the changes in the newborn’s epidermal barrier properties over the first 4 weeks of life, showing increased surface hydration, less transepidermal water movement under occlusion, and a decrease in surface pH. Diapered and non-diapered sites are indistinguishable at birth, but over the first 2 weeks of life diapered areas show consistently increased pH and hydration, thus setting the stage for IDD.

IDD results from the interaction of several factors associated with prolonged contact of the skin with a combination of both urine and feces (Tables 17.1–17.3). The wearing of diapers causes a significant increase in skin wetness and pH.9 Prolonged wetness leads to maceration of the stratum corneum due to disruption of the intercellular lipid lamellae.10

Weakening of the stratum corneum from excess hydration makes the skin more susceptible to damage by friction from the diaper. Fecal lipases and proteases are activated by the increased pH in the urine.11 In addition, the acidic pH of the skin surface is essential for maintaining a normal cutaneous microflora, which protects against invasion by pathogenic bacteria and yeasts.12 When diarrhea occurs, the fecal lipases and proteases increase in the diaper, leading to further damage to the stratum corneum. In the etiology of primary IDD, ammonia and Candida play less of a role than previously thought.

Differential diagnosis

Ordinarily the diagnosis is straightforward and uncomplicated. Many of the disorders listed in Box 17.1 present with subtle differences from IDD, particularly psoriasis and allergic contact dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis (AD) classically spares the diaper region, but infants with widespread AD may have involvement of the skin just above the margin of the diaper. Strict attention to the morphology and location of lesions, the absence of pustules or vesicles, and the absence of lesions in the creases should lead the physician to the correct diagnosis.

Treatment and care

Evidence-based practice guidelines for care of diaper dermatitis in hospitalized patients has reduced prevalence in high risk units.13

Mild topical steroid therapy (1% hydrocortisone ointment) covered by a barrier product three times daily, will clear the majority of IDD that does not respond to barrier products alone. The use of potent fluorinated topical steroids in the diaper region is not recommended as the natural occlusion of this area will promote increased absorption and may cause atrophy, striae, and adrenal suppression. When the practitioner is faced with a severely inflamed recalcitrant dermatitis in the diaper area, it is safe to use a week-long course of a medium-potency topical steroid to bring the eruption under control. The role of topical immunomodulators in the management of diaper dermatitis is unclear and cannot be recommended until further data are available on their safety and use in infants under 2 years of age.

Erosive perianal eruption

This entity presents with erosions and ulcers in the perianal skin and occurs most commonly between 6 weeks and 3 months of age, but can be seen at other ages. The etiology is almost universally associated with frequent stooling, either in breast-fed babies, children with diarrhea due to malabsorption, or infection in infants with short gut syndrome (Fig. 17.3A,B![]() ). This condition may eventuate into pseudoverrucous perianal papules in infants who undergo enterostomal closure, or following pull-through surgery for Hirschsprung disease.14 In mild cases, frequent diaper changes and use of a barrier product such as zinc oxide or triple paste with a low- to medium-strength topical steroid ointment applied two to three times daily, is helpful. In patients with short gut or other malabsorption syndromes the condition may be chronic, unremitting, and very difficult to treat. Incorporation of potato-derived protease inhibitor into a diaper barrier product has improved control of dermatitis in a small cohort of patients following colon resection for long-segment Hirschsprung disease.15

). This condition may eventuate into pseudoverrucous perianal papules in infants who undergo enterostomal closure, or following pull-through surgery for Hirschsprung disease.14 In mild cases, frequent diaper changes and use of a barrier product such as zinc oxide or triple paste with a low- to medium-strength topical steroid ointment applied two to three times daily, is helpful. In patients with short gut or other malabsorption syndromes the condition may be chronic, unremitting, and very difficult to treat. Incorporation of potato-derived protease inhibitor into a diaper barrier product has improved control of dermatitis in a small cohort of patients following colon resection for long-segment Hirschsprung disease.15

Pseudoverrucous papules

Pseudoverrucous papules (PVP; sometimes referred to as ‘pseudoverrucous papules and nodules’), and granuloma gluteale infantum, the more severe forms of Jacquet’s erosive diaper dermatitis, are probably best viewed as reaction patterns following chronic, unremitting irritation due to feces, urine, or a combination thereof.16 Pseudoverrucous papules were first described by Goldberg and colleagues17,18 in the setting of chronic diaper dermatitis, encopresis or peristomal skin irritation.

Well-documented precipitating factors leading to this condition include chronic diarrhea due to malabsorption, short-gut syndrome, or surgical repair of Hirschsprung disease or imperforate anus; leakage around stomas (either urinary or fecal); and chronic incontinence. Clinical features include dome-shaped papules, typically varying in size from 2 to 10 mm, often with a shiny, smooth, white or red surface (Fig. 17.4). Biopsy specimens reveal reactive acanthosis or psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis. The lesions regress when the irritating factor is removed. Recognition of this entity is important because pseudoverrucous papules and nodules may mimic other dermatoses, especially condyloma acuminatum, and unnecessary work-up for sexual abuse may be initiated.

Granuloma gluteale infantum

Granuloma gluteale infantum (GGI) was originally described by Tappeiner and Pfleger.19 It is rarely seen today and there are only 30 cases reported in the literature. Infants present with oval red-brown-purple dermal nodules on the gluteal surface and diaper area (Fig. 17.5).20,21 Rarely, lesions may be present in the intertriginous areas, including the neck and axilla. The long axis of the lesions runs parallel to skin lines. In the majority of affected infants there is a history of a preceding eruption in the diaper region treated with fluorinated topical steroids. Similar granulomas in the diaper region have been noted in adults who are incontinent or confined to bed.22 The etiology of GGI is unclear, but some have hypothesized that it is a skin response to the combined effects of inflammation, maceration, local infection with Candida, and use of fluorinated steroids. The sparing of deep folds suggests that occlusion by the diaper is necessary for its formation.

As for all forms of irritant diaper dermatitis, treatment should be directed at correcting the underlying cause of the chronic urine or fecal leakage whenever possible, as well as frequent use of a barrier product. Lesions generally resolve completely and spontaneously after a period of several months if the source of chronic irritation can be removed.

Senna laxative-induced blistering dermatitis in toddlers

Phenolphthalein was removed from all over-the-counter laxatives in 1999 and replaced with senna, an ornamental plant-derivative containing multiple anthraquinones. In a review of data from six poison centers in 2002, of 111 children less than 5 years of age who accidentally ingested senna-containing laxatives, 33% experienced severe diaper rash.23 The eruption is seen in infants or toddlers wearing diapers or pull-ups after overnight contact of the skin with large loose stools following accidental ingestion of chocolate squares of senna-containing laxatives. Therapeutic use of senna in a 3-year-old child with Hirschsprung disease and a pull-through procedure produced a similar eruption.24 This severe irritant contact dermatitis presents with distinct features, including a diamond-shaped lesion along the buttocks, linear borders aligning with the diaper edge, with usual sparing of the perianal area and gluteal cleft.24 Patients with this entity may be initially misdiagnosed with abusive scald burns (Fig. 17.6).

Granular parakeratosis

Granular parakeratosis is a rare disorder of keratinization characterized by retention hyperkeratosis. Its precise etiology is unknown, but it is generally viewed as a reaction to chronic irritation or possibly as a reaction to certain topical products such as zinc oxide, which are commonly used in the diaper area. It was originally described in the axillary region of adults, but there have recently been several reports in infants 9–22 months of age.

Infants usually present with asymptomatic, geometric yellow-brown, superficial scaling plaques with pronounced underlying erythema25 in areas of friction and pressure in the diaper region. A second pattern of linear warty papules in the inguinal area has also been described (Fig. 17.7).26

The cause of this peculiar entity is obscure, but immunohistochemical and electron microscopic studies suggest that there is a defect in the processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, which results in failure of the normal degradation of keratohyalin and clumping of keratohyalin filaments during cornification.27 These abnormal components result in the retention hyperkeratosis seen. Friction, moisture, and occlusion from diapers may trigger defective maturation of the stratum corneum at local sites in susceptible infants.

Treatment is empiric, with variable response to topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, calcipotriene cream, keratolytics, and emollients.25,28 The majority of cases clear spontaneously after months, but occasionally patients may have lesions for several years.

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis (ISD)

First described by Unna in 1887,29 ISD (see also Chapter 15) is a disease that affects infants usually in the first 2 years, with a distinct inflammatory eruption that primarily involves the scalp, retroauricular area, face, chest, diaper, and intertriginous areas. A precise definition is lacking; some physicians confine the entity to the presence of scalp scaling without inflammation called ‘cradle cap’ that affects the vertex of the scalp, whereas others only use the term if there is inflammation of the scalp and in other seborrheic sites.

Cutaneous features

The eruption usually begins under 6 weeks of age, but may occur up to 1 year or even later.30 Both sexes are equally affected. The vast majority of infants develop cradle cap alone; this is a collection of asymptomatic, greasy keratin on the vertex of the scalp (retention hyperkeratosis), without inflammation or involvement of other areas. A few patients develop multiple areas of involvement, including erythematous well-demarcated patches in the retroauricular area, eyebrows, along the sides of the nose, and involving the axillae, chest, and diaper area. The most commonly involved areas are the scalp and diaper area (Fig. 17.8). Although there is often a yellow, greasy scale on the erythema, this is not invariably present and is usually absent in the diaper area, where lesions consist of erythematous, well-demarcated patches involving the creases, but sometimes affecting the whole region. Scale is unusual or minimal in the diaper area. If there is invasion by Candida albicans, crusting and scaling may occur.31

Differential diagnosis

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate ISD from atopic dermatitis (AD). The scalp is often involved in both conditions; the pruritus with AD may not be evident early in infancy, and occasionally, ISD may be pruritic. The flexures are frequently involved in both conditions, although the antecubital and popliteal fossae are more commonly involved in AD and the axillae in ISD. Distinguishing features include xerosis of the skin and sparing of the diaper area in AD. Psoriasis in the diaper area is now more frequently recognized in infants, and is at times impossible to distinguish from ISD. The lesions are often confined to the diaper area as well-demarcated, erythematous and glistening plaques, with a thin, white scale. Infants seldom have the thick silvery scale that is normally seen with psoriasis in other areas. The typical inflammatory areas seen in ISD are absent in psoriasis.

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a potentially lethal disease that can mimic ISD in the diaper area and scalp. Unlike ISD, LCH lesions are crusted, ulcerative, petechial, and purpuric.

IDD usually spares the creases, and other eruptions in the diaper area have specific presentations that allow distinction from ISD.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The etiology of ISD in infants is probably the result of colonization and proliferation of the yeast Malassezia furfur (Pityrosporum ovale).32 Malassezia organisms thrive in an oily environment and may proliferate more in those infants whose hair is only shampooed once or twice a week, or who have emollients applied to the scalp. There is a marked decrease in the incidence of IDD in those infants whose hair is shampooed on a daily basis. A familial tendency may be relevant.33 Other theories of causation, including biotin and essential fatty acid deficiency, have not been proved.34

Prognosis and treatment

The majority of infants are cured within 2–4 weeks of treatment without recurrence35; and the relationship to adult disease is not known.33 Cradle cap can be treated with simple measures, including washing the scalp daily with a mild shampoo (Johnson’s Baby Shampoo®) following the application of oil (mineral oil, Aveeno oil®) to loosen the scale. A mild topical steroid cream (hydrocortisone 1%) three times a day may be necessary if there are inflammatory lesions. The etiology of ISD is thought to be an infection with a yeast organism, and antifungal measures have proved to be as effective as topical steroids.36 An antifungal shampoo (ketoconazole) daily, followed by the use of ketoconazole cream three times a day, is effective in treating the condition.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects adults and children. It is characterized clinically by typical scaly plaques, and pathogenetically by an accelerated epidermal cell turnover. The condition is being increasingly recognized in early infancy, and often affects the diaper area, particularly in those under 1 year.37 Of the one-third of cases of psoriasis that occur before age 20, 2% occur before the age of 2.38 There is often a family history of psoriasis in infants and children who develop the disease.38

Cutaneous findings

Caregivers complain of an eruption in the diaper area that is asymptomatic but unresponsive to standard treatment. Lesions appear as erythematous, glistening, well-demarcated patches with a thin white scale, or they affect the whole diaper area including the creases (Fig. 17.9A–C,D![]() ).39 Other areas are less frequently involved and include the face, scalp, trunk, and umbilical areas, with erythematous papules and plaques. The scale is often thin and lacks the characteristic silvery scale seen in older children and adults. Guttate lesions and nail changes are rare in infants.

).39 Other areas are less frequently involved and include the face, scalp, trunk, and umbilical areas, with erythematous papules and plaques. The scale is often thin and lacks the characteristic silvery scale seen in older children and adults. Guttate lesions and nail changes are rare in infants.

Although pustular psoriasis may occur in infancy, it does not affect the diaper area specifically. Patients present with fever and malaise, associated with either small pustules on an erythematous base or annular erythema with peripheral pustules. Occasionally, coalescence may lead to the formation of lakes of pus on the skin surface.

Extracutaneous findings

It is increasingly recognized that psoriasis may be associated with internal organ involvement. Joints are affected in 10% of patients, although this is uncommon in infancy. Geographic tongue may be seen, particularly in pustular variants. There is a small but well recognized increase of psoriasis in patients with Crohn disease. Patients with acute pustular psoriasis may develop a sterile osteomyelitis, and there have been a few reports of lung involvement in acute-onset psoriasis.

Differential diagnosis

At times it may be extremely difficult to distinguish between ISD and psoriasis. Many of the patients diagnosed with ISD who develop psoriasis later in life probably had psoriasis at the outset. Psoriasis is more chronic and more resistant to treatment, and usually spares the flexural areas, which are commonly involved in ISD. The umbilical area is commonly involved in both conditions, but particularly in psoriasis. Resolution of psoriasis in infancy is often very rapid, unlike in older children, adding to the difficulty of distinction from ISD. The lesions of atopic dermatitis are pruritic, poorly demarcated, and usually spare the diaper area.

IDD lesions have a typical pattern, spare the creases, and are not as well demarcated as those in psoriasis.

Etiology and pathogenesis

There is a strong genetic component in patients with psoriasis, particularly in the younger age groups.40 The pathogenesis of psoriasis is thought to involve an imbalance of T-helper cells resulting in a Th1-type cytokine reaction pattern. In addition, the cell turnover period is increased to 4 days in psoriasis, in comparison to a normal cell turnover period of 28 days.

Prognosis and treatment

The outcome of psoriasis in the younger age group is unknown. Many cases only have a single outbreak, others become chronic with frequent flares, and there are some patients who have a diagnosis of ISD or psoriasis in infancy who develop psoriasis many years later.

Daily bathing followed by the application of a mild topical steroid cream or ointment (hydrocortisone 1%) to the affected areas of the face and diaper area, and a moderate steroid ointment (triamcinolone) to the affected body areas three times a day, usually produces a rapid resolution of the lesions. If a mild steroid ointment is not sufficient to cause regression, a short trial of a medium-strength topical steroid in the diaper area may be given for a few weeks. It is important not to use anything stronger, as striae, atrophy, and iatrogenic Cushing syndrome have resulted from the use of potent topical steroids under the occlusive environment of the diaper. If complete regression is not seen within 3–4 weeks, a refined tar product, liquor carbonis detergens (LCD), can be compounded with the steroid in a 5–10% concentration. Salicylic acid is not recommended in neonates and infants, as systemic absorption can lead to salicylism.

Candidal diaper dermatitis with psoriasiform ID

This condition was first described in the 1960s as ‘diaper dermatitis with psoriasiform id.’41 It consists of a candidal eruption in the diaper area, followed a few days to weeks later by an explosive psoriasiform eruption on other areas of the body. It has been seen much less frequently in recent years.

Cutaneous findings

The condition usually affects infants between 6 and 24 months, but may occur earlier. The sexes are equally affected. There is an initial infection with Candida albicans in the diaper area42 that is severe, prolonged, or inadequately treated. The diaper lesions are erythematous patches with a peripheral scale, typical of Candida albicans in that area. Days to weeks later, often soon after the initiation of effective therapy of the diaper rash, there is an acute explosion of lesions anywhere on the body and face that consist of well-demarcated psoriasiform plaques (Fig. 17.10).43

Etiology and pathogenesis

The exact etiology of the psoriasiform id reaction is unknown. Id (also known as auto-eczematization) reactions occur in conjunction with several other infectious and inflammatory diseases, including tinea capitis and pedis, but the pathogenesis of the id reaction remains obscure. Some infants may have a genetic predisposition to developing psoriasis.

Prognosis and treatment

Lesions on the face are treated with a low-potency topical steroid cream 2–3 times a day, those on the body with a mid-potency topical corticosteroid cream 2–3 times a day, and those in the diaper area with an antifungal agent, usually a topical imidazole, 3–4 times a day. Cure occurs within 4–6 weeks and there is no recurrence, although there have been some reports of psoriasis developing some years later.41

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) may occur in the diaper region after exposure to fragrances, dyes, other components of the diaper itself, or to products applied by the caregivers to diapered skin.44,45 Weston and Weston46 showed that ACD may account for up to 20% of all cases of childhood dermatitis, refuting the notion that ACD is rare in children. Sensitization may begin as early as 6 months of age.47 Allergens to which infants and children have become sensitized include urushiol (poison ivy), nickel (in metal snaps on clothing), thimerosal, neomycin, chromates, Balsam of Peru, and formaldehyde and related preservatives.48

A specific form of ACD on the outer buttocks and hips was determined by patch-testing to be due to rubber components in the elastic bands of the diapers. The authors termed this entity ‘Lucky Luke dermatitis’ after the cartoon character who carries his gun holster in the same area (Fig. 17.11).49,50 Recently, Alberta and coworkers51 reported several infants with ACD caused by the various blue, pink, and green dyes used in diapers. Changing to dye-free diapers quickly alleviated the rash.

ACD may be present in the same areas of the diaper as IDD, but the morphology of the lesions is different in ACD, beginning with erythema and small vesicles and leading to an eczematous eruption with red papules or vesicles overlying areas of edema.44 Treatment with a medium-strength topical steroid provides rapid relief of symptoms, but removing the offending allergen is key to preventing recurrences.

Infections

Candidiasis

Candidiasis (yeast infection) (see Chapter 14) caused by the yeast Candida albicans, is the most common infection in newborns.52 Some 3% of infants are affected from the 2nd to the 4th month of life.53 Thrush (oral candidiasis) is common in early infancy, probably owing to infection from the mother’s vaginal canal. Candidiasis may be congenital, occurring in the first week of life through an ascending infection. Candidiasis usually affects the skin and mucous membranes only, but in certain circumstances, such as low birthweight or with systemic infections around the birth period, invasive systemic disease particularly affecting the lungs may occur.

Clinical picture

In congenital candidiasis, lesions may occur anywhere, including the face, feet and hands; the diaper area is not particularly involved. Occasionally, the nails may be hypertrophic. The lesions are erythematous papules and sheets of erythema, and are present soon after delivery, beginning at birth or in the first week of life. Candidal diaper dermatitis usually begins around 6 weeks of age and is seldom seen before this time. It is common to have a history of antibiotic use or diarrhea preceding the appearance of the eruption.

The entire perineal area, including the creases, may be affected. The morphology of the lesions takes two forms: a diffuse erythematous patch extending over the perineum with a peripheral scale, or small pink papules surmounted by a scale, and coalescence in some areas (Fig. 17.12A,B,C![]() ). The more classic picture of a beefy-red diaper area with satellite pustules (Fig. 17.12B) is less common, possibly because of earlier treatment with antifungal agents. Infants should be examined for evidence of oral candidiasis (thrush), which typically presents as small white patches on the buccal mucosa.

). The more classic picture of a beefy-red diaper area with satellite pustules (Fig. 17.12B) is less common, possibly because of earlier treatment with antifungal agents. Infants should be examined for evidence of oral candidiasis (thrush), which typically presents as small white patches on the buccal mucosa.

Differential diagnosis

In IDD, the creases are spared. Perianal Streptococcus infection appears as painful, beefy-red lesions surrounding the anus. ISD presents with erythematous patches: it does not have the peripheral scale or the satellite papules or pustules seen in candidiasis.

Etiology and pathogenesis

In congenital candidiasis, there is an ascending infection causing a chorioamnionitis whereas in neonatal candidiasis, the lesions are formed when Candida albicans is excreted in excessive amounts in the feces. This is often preceded by the use of antibiotics and diarrhea of any cause. The significance of recovering Candida albicans from the diaper area is difficult to interpret, as the organism may be recovered in any irritant skin condition in the diaper area after 72 h,54 and may even be present in small amounts on normal skin. However, when candidal infection occurs, the organism is present in much larger numbers in the skin and feces.55,56 Candida has the ability to invade through the epidermal barrier by liberating keratinases.

Prognosis and treatment

In congenital candidiasis, in full-term infants, the prognosis is excellent and treatment is seldom necessary, or a topical antifungal may be warranted. In neonates weighing less than 1000 g, systemic involvement may occur requiring treatment with amphotericin or fluconazole.57 Studies comparing the various treatment options for Candida diaper dermatitis are lacking.58 Treatment with topical anti-candidal therapy, either nystatin (cream or ointment) or one of the imidazoles (clotrimazole, miconazole, or ketoconazole), three times daily, is generally effective in producing resolution in about 2 weeks. A formulation of miconazole 0.25% compounded in zinc oxide and petrolatum (Vusion®, Barrier Therapeutics, Princeton, NJ) has recently been approved specifically for the treatment of documented Candida diaper dermatitis.59 The use of additional hydrocortisone 1% to one of the above agents provides an anti-inflammatory effect and may promote more rapid resolution of the eruption, but this has not been studied in formal clinical trials. Potent topical corticosteroids should be avoided.

Burow’s solution (5% aluminum subacetate) or normal saline compresses may be useful in inflammatory lesions. In a double-blind study, the oral use of nystatin (to eliminate Candida from the bowel), in conjunction with topical nystatin did not affect the outcome of the dermatitis more favorably than topical nystatin alone;60 however, if oral candidiasis is present, oral nystatin suspension is required both to treat the thrush and to prevent recurrence of the diaper rash. Oral fluconazole (6 mg/kg as a loading dose and 3 mg/kg/day for 1–2 weeks) is very effective in treating mucocutaneous Candida infection. However, if topical therapy is ineffective, an alternative diagnosis or the presence of a concomitant immunodeficiency should be considered.

Staphylococcal infection: impetigo/staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS)

Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection seen in infants and children,61 and the most common organism causing impetigo in infants is Staphylococcus aureus, phage type 2. The diaper area is frequently affected with lesions, which appear as flaccid bullae. A generalized form of staphylococcal infection caused by a number of exotoxins of phage 2 is known as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) (see Chapter 12). Infants and young children are primarily affected, but the disease has been reported in adults, usually in immunocompromised patients, in whom there is a sizable mortality rate. The diaper area of the neonate is often affected by SSSS. Very occasionally, a Pseudomonas exotoxin may cause lesions that resemble SSSS. Streptococcus pyogenes is rarely the sole cause of impetigo in the neonate.

Cutaneous findings

The infection can occur at any time and in any location, but often presents in the first 2 weeks of life in the diaper area. Constitutional signs are absent. The lesions may be single or multiple, and are either flaccid bullae or moist, superficial erythematous erosions (Fig. 17.13A) that have a thin peripheral collarette of scale after the bullae rupture. Initially pus is not present and there is serous fluid in the bullae. After a few days, the fluid becomes cloudy and pus is seen in the dependent area of the bulla. The lesions are superficial and there is no scarring once resolution occurs. A culture from the lesions or the umbilical stump usually yields a heavy growth of S. aureus.

SSSS presents with skin findings alone, but occasionally there may be a short prodrome of sore throat or conjunctivitis, followed by the release of toxin. The skin is sensitive to the touch and erythematous, with widespread exfoliation and fissuring around the mouth. Areas of involvement can be limited to the neck or diaper area (Fig. 17.13B). The mucous membranes are unaffected. The organisms can be cultured from the nose, pharynx and umbilicus, but not the skin. The Nikolsky sign is positive.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The most common entry point in neonates is an infected umbilical stump. The eruption is caused by S. aureus phage type 2. Locally produced exfoliative or epidermolytic toxins A and B bind to desmoglein 1 in the desmosomes, with resultant proteolysis.62,63 The toxins cleave the granular layer.64 In bullous impetigo, the exfoliating toxin is confined to the area of infection. In SSSS the exotoxin is spread hematogenously from a local source.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to rule out other causes of blistering in the neonate. The most important are herpes simplex infection and epidermolysis bullosa. In herpes simplex infection, the vesicles are grouped and small, whereas in impetigo, they tend to be larger bullae. Erythema toxicum presents with small pustules on an erythematous base, and small pustules are also seen with transient neonatal pustular melanosis, acropustulosis of infancy, and congenital candidiasis. Lesions are often smaller than those seen with impetigo and are pustular, whereas in impetigo the bullae are larger and flaccid or superficial erosions. Other rare causes of bullae in the neonate include pemphigus, pemphigoid, and incontinentia pigmenti, although these do not usually present with large flaccid bullae or erosions, and the diaper area is not specifically involved.

Prognosis and treatment

Both bullous impetigo and SSSS have a good prognosis in infants and children. It is important to treat bullous impetigo immediately to prevent spread in the nursery. Oral antibiotics such as cloxacillin, cephalexin, and erythromycin are all effective as a 10-day course and lead to rapid cure in 5–7 days, with no scarring or recurrence. Some centers use IV antibiotics. In methicillin-resistant cases, it may be feasible to use topical fusidic acid, mupirocin or retapamulin if the lesions are localized.65

Perianal and perineal bacterial dermatitis

Infections with β-hemolytic streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus may take several forms in this region, including perianal dermatitis, intertrigo, cellulitis, vulvovaginitis, and balanoposthitis (see Chapter 12).66–68 Honig and colleagues69 reported a case series of infants less than 5 months of age with streptococcal intertrigo involving the inguinal, axillae, limbs and neck folds. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis (PSD)67 is the most common presentation and is seen more frequently in males. A recent report suggests that there may be a shift occurring in the microbiology of this entity with Staphylococcus aureus predominance.70

Cutaneous findings

PSD presents as sharply circumscribed perianal erythema with occasional fissures, often with a sticky yellowish exudate that accumulates at the periphery (Fig. 17.14A,B![]() ). Pustules may also be present at the border of the lesions. The surface is often tender to touch, and there are associated symptoms of itching, painful defecation, or blood-streaked stools.

). Pustules may also be present at the border of the lesions. The surface is often tender to touch, and there are associated symptoms of itching, painful defecation, or blood-streaked stools.

Extracutaneous findings

Infants may present with constipation, pain with defecation, or even encopresis. Fever is rare. Guttate psoriasis, which is typically associated with streptococcal pharyngitis, may be seen with PSD (Fig. 17.14A). Therefore, any patient with new-onset guttate psoriasis should have an anogenital examination and appropriate cultures should be obtained.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The mechanism of infection may be related to tropism of specific GABHS (group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus) strains to this area, but colonization may occur through the passage of swallowed GABHS in the gastrointestinal tract, or orodigital contamination from a focus of GABHS pharyngitis.68 Communal bathing has contributed to familial outbreaks.71 Similar clinical presentations have been reported with cultures positive for S. aureus strains.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, cutaneous candidiasis, pinworm infestation, Crohn disease, and sexual abuse. The diagnosis is confirmed by bacterial culture of the affected area. Certain laboratories may use media selective for enteric pathogens when plating swabs from this area, so it is essential to specifically request isolation of GABHS. If culture is negative but clinical suspicion is high, culture of the pharynx may provide additional evidence for GABHS.

Treatment and care

Treatment with a 10-day course of oral penicillin V or amoxicillin, with or without adjunctive topical mupirocin ointment applied twice daily, is usually curative. Erythromycin may be used in penicillin-allergic patients. Recurrent disease may prompt the need for repeated or more prolonged oral therapy. Repeated recurrences are uncommon, but may require strategies similar to those used to eliminate streptococcal carriage from the pharynx.

Ecthyma gangrenosum

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is due to direct skin inoculation or more commonly to septicemia caused by infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It may occur anywhere on the skin surface, but over 50% present in the perineal/gluteal area. It usually occurs in immunocompromised infants but occasionally occurs in healthy children with transient neutropenia from another infection.72 Skin lesions begin as an erythematous macule that rapidly enlarges into a gray nodule, necrotic hemorrhagic bulla, or ulceration with a bright red surrounding areola and a central eschar.73 Differential diagnoses include cutaneous anthrax74 as well as opportunistic pathogens, including Aeromonas, Aspergillus, and Mucor. Treatment is with anti-pseudomonal systemic antibiotic therapy initiated as soon as possible because of the rapid extension of the disease.75

Diaper dermatophytosis

Dermatophyte infections of the diaper region are rare but often misdiagnosed. Isolated organisms include Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and T. verrucosum, as well as Epidermophyton floccosum.76,77 Often other family members, particularly the patient’s parent, have associated tinea pedis or cruris. Standard remedies for IDD or the use of topical nystatin (which is efficacious against Candida but not dermatophytes) will not alleviate the problem and may exacerbate it. Examination shows annular, erythematous, scaling papules and plaques in the diaper region. In chronic cases, deeper follicular papules and pustules may be present (Fig. 17.15). Superficial infection responds well to topical antifungals, but when lesions are extensive or there is deeper follicular involvement, treatment with oral antifungals such as griseofulvin, fluconazole, or terbinafine may be required; experience with the use of terbinafine in neonates and very young infants is rather limited.

Herpes simplex infection

Primary herpes infection (see Chapter 13) presents with painful vesicles, clustered on an erythematous base, 2–8 days after contact with an infected individual. Neonatal herpes may present in the diaper region following breech delivery of an infant whose mother has genital HSV. The diagnosis of genital HSV in an older infant or child may raise the suspicion of sexual abuse, although innocent transmission from an infected caregiver or parent may occur. Materno-fetal transmission of HSV resulting in neonatal HSV infection is discussed in Chapter 13.

Condyloma acuminata and mollusca contagiosa

Verrucae are caused by cutaneous infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV); the infection is very common in children, although rare in neonates and infants. There are in excess of 100 HPV subtypes, most of which produce self-limited infection; a few subtypes in the genital area lead to malignancies. When verrucae affect the genital area they are known as condyloma acuminata. At least 30–40 subtypes are implicated in causing condyloma acuminata (see Chapter 13).78 Acquisition in infancy is usually through maternal transmission. The incubation period is unknown and may be anywhere from 1 to more than 24 months. They can occur on any part of the perineum, including the vaginal area and around and extending into the anus. Lesions appear as asymptomatic, flesh-colored papules that may coalesce to form plaques. They have a characteristic verrucous, velvety surface (Fig. 17.16A,B,C![]() ).

).

Although it is well recognized that condyloma may be the result of child abuse, most cases in young infants are either vertically acquired or from unknown sources.79 The exact percentage of cases acquired from sexual abuse in young infants is unknown and probably quite low, yet it is important to consider the possibility of abuse in all cases of genital HPV infection. There is a high rate of spontaneous resolution. Treatment regimens include imiquimod, podophyllin, and surgical removal (see Chapter 13).

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a poxviral infection of the skin characterized by discrete single or multiple, pink or flesh-colored, umbilicated papules.80 There are four subtypes that are not area-specific. It is rarely seen in the neonatal period, but increases in incidence in early childhood; 80% of patients are under 8 years of age.81 The lesions are thought to be spread by autoinoculation; they tend to cluster in creases such as the axillae, the antecubital and popiteal fossae, and the diaper area (Fig. 17.17). The latter often raises the specter of child abuse, but supportive evidence is usually lacking and genital involvement is common.81 The disease is self-limited and often resolves with severe inflammation. Treatment includes curettage with topical anesthetics, liquid nitrogen (not an option in infants or young children), cantharidin and podophyllin.

Coxsackie viral exanthem (hand, foot, and ‘butt’ exanthem)

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is caused by various serotypes of coxsackie virus (CV), including A16, A5, A6, A9, A10, B1, and B3 (see Chapter 13). Infection with enterovirus 71 may cause a similar clinical presentation. The disease tends to be more severe in children under 5 years of age. Lesions consist of small red macules that rapidly evolve into ovoid vesicles. In the perineum, vesicles are rarely seen (Fig. 17.18A,B,C![]() )82 except in patients infected with CVA6. Of affected children, 31% will have lesions in the buttocks or perineum, particularly those who are still wearing diapers (see Chapter 13).83 In March 2012, the Centers for Disease Control reported outbreaks of CVA6 in several states.84 Skin manifestations of this new strain include larger vesicles with widespread skin involvement and a predilection for active sites of dermatitis in atopic patients (Fig. 17.18A,B

)82 except in patients infected with CVA6. Of affected children, 31% will have lesions in the buttocks or perineum, particularly those who are still wearing diapers (see Chapter 13).83 In March 2012, the Centers for Disease Control reported outbreaks of CVA6 in several states.84 Skin manifestations of this new strain include larger vesicles with widespread skin involvement and a predilection for active sites of dermatitis in atopic patients (Fig. 17.18A,B![]() ). Nail shedding occurs following recovery.

). Nail shedding occurs following recovery.

Nutritional and metabolic disorders

Zinc deficiency

Zinc is an essential mineral element that is necessary for the normal function of humans (see Chapter 18). An acute deficiency of zinc, through various mechanisms, is associated with a specific clinical picture in the skin. The dermatitis affects the periorificial areas of the face, the diaper area, and acral sites. Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare, recessively inherited disorder caused by a lack of zinc transfer from the small intestine.85 A similar and much more frequent clinical picture is seen with other causes of low zinc levels, such as in breast-fed premature babies whose need for zinc outstrips the supply available in breast-milk. In rare cases, a similar etiology can occur in term infants whose mothers’ breast-milk is deficient in zinc.85 Zinc deficiency can also occur in malabsorption states, particularly when associated with cystic fibrosis (see below). Previously, zinc deficiency was reported in patients on parenteral alimentation, but it is rarely if ever seen now, as zinc is routinely added to the feeds. A picture resembling zinc deficiency may also be seen with other metabolic diseases, such methylmalonic acid deficiency, biotin deficiency, essential fatty acid deficiency, and vitamin A acid deficiency.

Clinical presentation

The typical presentation is in a neonate or infant who develops a crusted, scaling, erythematous dermatitis around the face and in the diaper area (Fig. 17.19A,B). Lesions on the face assume a characteristic horseshoe appearance around the mouth. The periorbital area may also be involved. In the diaper area, lesions often affect the area around the anal cleft, with sharply demarcated erythema, superficial scale, and crusting at the periphery. Paronychia with candidal infection, maceration, and dermatitis are seen in the acral areas of the fingers and toes. Bullous lesions are rarely present on acral skin.

Extracutaneous manifestations

It is common to have marked irritability, diarrhea, sparse hair or alopecia, and recurrent infections, particularly with Candida albicans, but these may be absent early in the course of the disease, skin manifestations being the only finding. Nails may be dystrophic.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The etiology of AE is thought to be an abnormality in the region of chromosome 8q24.3 affecting the zinc transporter system at the level of the small intestine.86 Zinc is a cofactor in many enzymatic responses, hence the heterogeneity of the clinical signs in the disease. The serum zinc level is low; blood should be collected in a plastic container to avoid erroneously high laboratory levels. Alkaline phosphatase levels may also be low, as zinc is a cofactor in this enzyme.

Prognosis and treatment

Oral zinc supplementation, given as zinc sulfate (3–5 mg/kg per day) or as zinc gluconate (which is better tolerated but more expensive), results in the rapid reversal of the eruption and associated symptoms. Irritability is the first symptom to disappear. Patients with the genetic form of AE require treatment for life. Those infants with zinc deficiency due to a lack in breast-milk require zinc supplementation if breast-feeding is continued, but once formula or solid food is started the supplemental zinc is no longer needed.87

Disorders that resemble acrodermatitis enteropathica

Biotin deficiency and certain organicacidurias88 (see Chapter 18) may present with dermatitis of periorificial regions, including the diaper area, often in association with alopecia and changes in hair texture. The specific entities reported include deficiency of vitamin B12 or isoleucine from restrictive diets or methylmalonic acidemia, propionic academia, glutaric aciduria (type 1),89 maple syrup urine disease,90 ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency,91 and citrullinemia.92 Cystic fibrosis may present in infancy with failure to thrive and an AE-like eruption.93 Edema is usually severe in cystic fibrosis because of marked hypoalbuminemia and the characteristic mucosal and paronychial lesions of AE are usually absent.

Biotin deficiency may be induced by a diet high in raw egg white, which contains avidin, preventing the absorption of biotin. It has also been reported during prolonged parenteral nutrition containing inadequate replacement of biotin. Several autosomal recessive disorders may present with AE-like eruptions because they require biotin as a cofactor, including methylmalonic acidemia, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and holocarboxylase deficiency.94 Children undergoing long-term treatment with valproic acid for seizure disorders may have low biotin levels.95

Miscellaneous

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH; see also Chapter 26) is a disease of unknown origin that is caused by an accumulation of bone marrow-derived cells that originate from the granulocyte series. Cells divide into the macrophage and dendritic cell series. LCH is a dendritic cell disorder and is the only histiocytic disease to affect neonates. The cells in this group of histiocytosis are all S100 and CD1a positive and have Birbeck granules on electron microscopy. The diaper area is often involved.

Clinical presentation

LCH affects 2.6 children per million child-years,96 with boys slightly more affected than girls. Spontaneous regression often occurs in limited forms, so the incidence may be higher than recorded. The age group most often affected is from 1 to 4 years, but the disease may occur at birth and can affect any age. After bones, the skin, including the gums, teeth, and nails, is most commonly affected (40%).97 Skin lesions may be single, few in number, or disseminated, and are the presenting sign in 50% of cases.98 LCH in the newborn may involve the skin alone – congenital self-healing histiocytosis (Hashimoto–Pritzker disease), in which the majority of cases have nonspecific skin findings and are usually undiagnosed for a few months.99 The most common sites affected in skin LCH are the trunk, scalp, behind the ears, the diaper area, and the skin folds. Lesions are protean in their presentation: papules, nodules, vesicles, erosions, ulcerations, petechiae and purpura, scale and crusting can all be present either alone or together (Fig. 17.20A). The color varies from erythematous to yellow or brown. Lesions in the diaper area are erythematous with peripheral petechiae. Ulcerations or atrophy involving the inguinal creases may be present (Fig. 17.20B).

Extracutaneous findings

Any organ may be affected in LCH, but it is unusual in the kidneys and gonads. In children under 2 with LCH, the disease is frequently disseminated (Letterer–Siwe disease), with skin and other organ involvement. The most common organ of involvement is bone (74%), followed by the skin (40%), lymph nodes (14%), and all other organs (<10%).99

Etiology and pathogenesis

The precise etiology is unknown. Genetic factors have been implicated, as the disease is more common in monozygotic twins and in families. HLA studies have varied, but immune factors are thought to play a role. The theory of a reactive process invokes environmental factors, including malignancy.

Differential diagnosis

Owing to the diversity of the symptoms and signs, it is easy to miss the diagnosis. Conditions such as neuroblastoma, congenital leukemia, mastocytosis, and hemangiomas all present with nodular lesions. Pustular lesions such as erythema toxicum, neonatal pustular melanosis, and acropustulosis of infancy can all mimic LCH. The dermatitic variant is easily confused with ISD. Petechiae are a helpful sign of differentiation. Any patient resistant to standard treatment for ISD should be evaluated for LCH; both conditions affect the scalp and diaper area, and both have erythema and scaling. There is more crusting in LCH, and the presence of petechiae is a valuable distinguishing sign.

Prognosis and treatment

The diagnosis should be established based on biopsy and skin markers CD1a and S100 staining. The prognosis is not affected by the clinical appearance or the histology. In single-system skin disease, or where few skin lesions are present, it is important to monitor carefully for signs of other organ involvement and the appearance of diabetes insipidus. The prognosis in this group is good.99 In the multinodular group of LCH called Hand–Schüller–Christian disease, the lesions are chronic and there may be an association with diabetes insipidus.100 The multinodular groups have a better prognosis than the disseminated Letterer–Siwe disease, where the mortality rate under the age of 2 years is 50%.101 There are no good data on the definitive treatment of skin LCH. Treatment is geared toward the well-being of the patient, the number of organs involved, and the desire to minimize late effects. LCH involving multiple organs requires treatment (see Chapter 28).102

Infantile perianal pyramidal protrusion

First described in 1996,103 this entity consists of a protrusion around the anus that is often related to diarrhea, chronic constipation, or less commonly lichen sclerosus.104 It has also been described in the literature as tags or skin folds.105 The terminology has now been simplified to infantile perineal protrusion (IPP).106

Cutaneous findings

IPP is fairly common, affecting up to 11% of prepubertal girls.105 It has been reported in families,104 and is almost exclusively seen in females.105 The age range is usually between 1 and 30 months, but it has been reported at birth.105 Parents, when prompted, will often give a history of chronic constipation or diarrhea as the initial event, prior to the appearance of IPP. The lesion may be asymptomatic or there may be pain on defecation; it is sometimes associated with fissuring. IPP usually appears on the perianal mucous membrane in the midline just anterior to the anal opening; it may less commonly be seen on the posterior aspect of the anus.107 It is a pyramidal soft tissue protrusion with a tongue-like lip (Fig. 17.21).104 The surface is smooth. The pathology is unremarkable, those having lichen sclerosus changes showing evidence of the disease on biopsy.106

Extracutaneous findings

There may be a history of diarrhea or constipation from various causes.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The cause is unclear. IPP may be familial, functional (diarrhea or constipation), and lichen sclerosus-associated.108 Neither weakness of the median raphe of the perineum, nor perineal constitutional weakness have been proven to be associated with IPP.

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions affecting the anal area should be considered. These include hemorrhoids, skin tags, condyloma acuminata, tag associated with anal fissure, inflammatory bowel disease, rectal prolapse, perineal midline malformation, and infantile hemangiomas.104

Prognosis and treatment

Many cases resolve completely, and persistence is less common.107 Attending to either constipation, diarrhea or fissuring may be helpful in accelerating the resolution. If lichen sclerosus is present, then treatment with high-potency corticosteroids is useful. Observation, with petrolatum applied to the area is usually all that is needed.

Nascent hemangioma

Infantile hemangiomas (see Chapter 21) located in the perineum frequently become ulcerated, and this may actually be the presenting finding in a minority of patients. In these cases, an infant will be born with or develop an ulceration in the perineum in the first few days of life prior to a hemangioma being evident. Close inspection will often reveal telangiectasia or vascular papules at the margin of the ulceration, or occasionally in the surrounding skin (Fig. 17.22A). Days to several weeks later, a superficial plaque-type or minimal/arrested growth hemangioma will develop in the region (Fig. 17.22B![]() ). Undiagnosed ulceration due to nascent hemangioma may be misdiagnosed as a rapidly expanding bacterial or viral infection, thermal burn, or child abuse.109 The etiology of ulceration in nascent hemangiomas is unclear, but may be related to rapid apoptosis of endothelial cells in a portion of the evolving hemangioma.

). Undiagnosed ulceration due to nascent hemangioma may be misdiagnosed as a rapidly expanding bacterial or viral infection, thermal burn, or child abuse.109 The etiology of ulceration in nascent hemangiomas is unclear, but may be related to rapid apoptosis of endothelial cells in a portion of the evolving hemangioma.

Lichen sclerosus (LS)

This disease of unknown origin affects the genital area of female children with a well-recognized clinical and histologic picture. The two main ages of presentation are in prepubertal and postmenopausal females. The male equivalent of LS is called balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). Autoimmune, genetic and other etiologies have been implicated but not proved.110 Cases during infancy are uncommon, but the presence of histologic changes of LS in boys with congenital phimosis and a documented association with perineal pyramidal protrusion suggests than onset may occur quite early in infancy.111 The mean age of presentation is 5 years but it may occur anywhere from 1–12 years. The eruption may be asymptomatic, but usually presents with pruritus in the genital area, and constipation. Pain, dysuria and bleeding may also occur in girls and phimosis in boys with BXO.112

Constipation is related to fissuring of the perianal skin, pain on defecation and subsequent atony of the bowel associated with holding the stool. The classic clinical picture is of a white, glistening, atrophic vulvar area, often with accentuation of the veins and wrinkling of the skin (Fig. 17.23A). The lesions may extend onto the anal area in a figure-of-eight distribution (Fig. 17.23B![]() ). Hemorrhagic areas and petechiae may be seen (Fig. 17.23C

). Hemorrhagic areas and petechiae may be seen (Fig. 17.23C![]() ). It is important to differentiate LS from child abuse and herpes simplex infection. If left untreated, adhesions, flattening of the clitoris, and narrowing of the vaginal opening may occur. Response to potent topical steroids is excellent, but recurrence may occur.113 In boys, circumcision may be necessary to relieve the balanitis.

). It is important to differentiate LS from child abuse and herpes simplex infection. If left untreated, adhesions, flattening of the clitoris, and narrowing of the vaginal opening may occur. Response to potent topical steroids is excellent, but recurrence may occur.113 In boys, circumcision may be necessary to relieve the balanitis.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (see Chapter 10) presents as papules that develop into pustules and then rapidly expand into painful deep ulcerations surrounded by a violaceous border. Pathergy often occurs. Although rare in infants, a case has been reported in a 3-week-old infant presenting with perineal lesions.114 Crohn disease should be considered when lesions of pyoderma gangrenosum develop in the perianal region, particularly with features of skin tags, perianal fissuring, and a history of diarrhea or constipation.115

Chronic bullous disease of childhood (CBDC)

CBDC or linear IgA disease is an acquired blistering disorder that involves the skin and mucous membranes. The etiology of CBDC is unknown (see Chapters 10 and 11); studies implicating infectious, drug, or autoimmune diseases have been inconclusive. Commonly, preschool children present with fever or other constitutional findings, followed by large tense bullae that are annular or polycyclic. The lesions are described as resembling a string of pearls. The underlying skin is normal. The diaper area is characteristically involved, with other common areas that include the face, trunk, and legs, although any site can be affected (Fig. 17.24).116 Although not recognized initially, mucous membranes, particularly the oral mucosa, are frequently involved. Erosions and occasional intact bullae are seen. Conjunctival erosions are not uncommon. The bullae are subepidermal and filled with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates a linear band of IgA staining at the dermo–epidermal junction. The prognosis for remission without treatment is between 3 and 5 years, although the disease may persist into adult life. Treatments include dapsone, sulfapyridine, and prednisone, with good results. When the lesions heal, there are no recurrences.117

Bullous pemphigoid (BP)