116 Dialysis-Related Emergencies

• Infection is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in dialysis patients. Tunneled lines and temporary dialysis catheters are more likely to become infected than grafts and native arteriovenous fistulas.

• The differential diagnosis of hemodynamic instability in a hemodialysis patient is dependent on the associated signs or symptoms (e.g., fever, chest pain), as well as the duration and speed of onset of the instability.

• Early vascular surgery consultation is necessary for patients with clotted hemodialysis access.

• Peritonitis is a common infection associated with peritoneal dialysis. Turbidity is one of the earliest signs of infection.

• Empiric treatment of peritoneal dialysis–associated peritonitis should include intraperitoneal antibiotics with both gram-positive and gram-negative coverage.

Scope

In the United States, in excess of 380,000 patients with renal failure rely on some form of dialysis as life-sustaining renal replacement therapy. More than 90% of these patients are managed with hemodialysis, whereas about 7% use peritoneal dialysis (PD).1 The most common complication associated with either dialysis modality is infection, although many access site malfunctions and dialysis-related emergencies prompt visits to the emergency department (ED) by this population.

Hemodialysis

Structure and Function

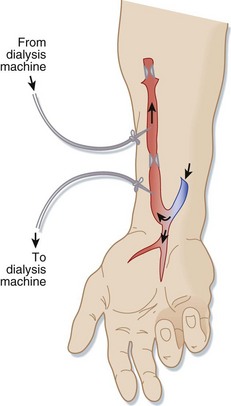

Connecting an artery (usually in the forearm) directly to a vein via surgery creates a native AV fistula (Fig. 116.1). Over months, the increased blood flow creates a larger, stronger vein with adequate blood flow for dialysis. Native AV fistulas are less likely than other forms of hemodialysis access to become infected or form clots.

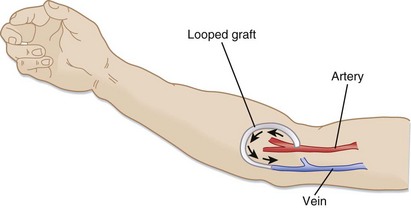

Synthetic AV grafts (Fig. 116.2) are used when forearm veins are unsuitable for native grafts. Synthetic grafts can be used within weeks of placement; however, they have higher infection and clotting rates than native AV fistulas do.

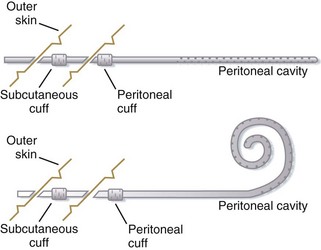

Central venous catheters (Fig. 116.3) are used when dialysis access is needed before permanent AV grafts have had time to mature or when fistula or graft surgery fails. Approximately 25% of the hemodialysis patients in the United States use central venous catheters as their primary vascular access. Tunneled, cuffed catheters have a lower infection rate than nontunneled catheters do. All these catheters have a double lumen and are at higher risk for infection and clotting than AV fistulas or grafts are.

Complications

Infection

Infectious complications are among the foremost causes of morbidity and mortality in hemodialysis patients. The risk for infection results from both impaired immune function related to the renal failure (e.g., altered granulocyte function in uremia) and repetitive access of the vasculature across the protective skin barrier. Vascular access is the source of bacteremia in 48% to 73% of infected hemodialysis patients.2

Clinical findings may include fever, hypotension, altered mental status, skin infection at the access site, and severe sepsis. Patients with diabetes may have ketoacidosis. The differential diagnosis of the various clinical findings in hemodialysis patients is described in Table 116.1.

Table 116.1 Differential Diagnosis of Various Clinical Findings in Hemodialysis Patients

| CLINICAL FINDING | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND CRITICAL ACTIONS |

|---|---|

| Hypotension |

If onset immediately after first hemodialysis session, consider dialysis disequilibrium syndrome.

If the onset is gradual, consider dialysis dementia.

Infection is a common cause of altered mental status (delirium) in hemodialysis patients, and the presence of a fever should prompt antibiotic administration and a search for the source.

Also consider stroke, hypotension, drug effect, seizure, and metabolic derangement (acidosis, hyperkalemia).

Consider line infection in patients with warmth or erythema of the skin overlying the dialysis access site.

Consider sepsis if the patient is hypotensive or in shock; obtain blood for culture and administer antibiotics.

Fever is almost always due to infection, but overheated dialysate is a potential cause.

Removal or exchange of an infected catheter is advisable because a bacterial biofilm can form rapidly in the lumens of most indwelling central venous catheters and serve as a source of continued infection. Systemic antibiotics given alone are relatively ineffective in eradicating infection if the catheter is not removed. There are occasional protocols that have demonstrated catheter salvation, but none have done so reliably. Catheter removal with delayed replacement is required in patients who are clinically unstable, who have metastatic infectious complications, or who have tunnel infections.3 Tunneled catheters can be replaced with temporary nontunneled catheters or can be changed over a guidewire, thus avoiding disruption of the patient’s dialysis schedule.

Thrombosis

Thrombosis of hemodialysis access grafts and catheters is a significant cause of morbidity. Failure of hemodialysis grafts is mainly due to progressive intimal hyperplasia at the venous anastomosis and resultant decreased flow and graft thrombosis.4

Thrombolytic agents can be initiated in consultation with a vascular surgeon. Several different thrombolytic regimens can be used. One protocol involves the use of 2 to 4 mg of alteplase infused through an 18- to 22-gauge intravenous line while waiting for the availability of angiography. If the wait time exceeds 30 minutes, an additional 2 mg is given.5 Care must be taken to confirm that the intravenous tubing has actually been inserted into the graft pointing toward the occlusion and not into surrounding tissue or another vessel before infusion of the thrombolytic agent. The arterial limb of the graft should also be occluded while the thrombolytic agent is being infused.

Bleeding

Hemodialysis patients are at risk for hemorrhage from other sites because of anticoagulation during dialysis. Platelet dysfunction secondary to uremia also contributes to hemorrhage in patients with renal failure, and it is only partially corrected by hemodialysis. Administration of desmopressin (DDAVP) (0.3 mcg/kg intravenously with 50 mL saline over a 3-minute period, 0.3 mcg/kg subcutaneously, or 2 mcg/kg intranasally) improves the hemostatic function of platelets and is useful in treating hemorrhage in hemodialysis patients. The maximal effect of DDAVP occurs after 1 hour, and if immediate hemostasis is needed, 10 units of cryoprecipitate can be infused over a 30-minute period.4

Pseudoaneurysm

Pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur with prosthetic grafts, but they can also develop with autogenous access. Duplex ultrasound can be used to distinguish between pseudoaneurysms and other perigraft fluid collections. Small puncture site pseudoaneurysms can sometimes be monitored, but pseudoaneurysms at the anastomosis of the graft require surgical or endovascular revision and are often associated with infection. Vascular surgery consultation is necessary for suspected pseudoaneurysms.4

Dialyzer Reactions

Patients undergoing their first hemodialysis session or those switching to a new dialyzer may experience anaphylaxis or an anaphylactoid reaction to a component of the dialyzer or dialysate. Anaphylactoid reactions have been observed with dialyzers made of cuprophane and with polyacrylonitrile dialysis membranes (particularly in patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors). Treatment consists of epinephrine, antihistamines, and steroids.6

Tips and Tricks

Use of Hemodialysis Graft or Catheter for Emergency Vascular Access

Peripheral hemodialysis access sites may be used for placement of an intravenous catheter in an emergency when no other access is available:

Central venous hemodialysis access may also be used in an emergency when no other access is available:

Dialysis Disequilibrium Syndrome

The mainstay of treatment is prevention by avoiding rapid shifts in serum osmolarity during dialysis. Symptoms are usually self-limited and resolve within a few hours; severe cases can be treated by raising serum osmolarity with infusions of hyperosmolar solutions such as hypertonic saline or mannitol, in consultation with a nephrologist.7,8

Dialysis Dementia

1. An epidemic form believed to be due to contamination of dialysate with aluminum, which is usually excreted by the kidneys (the use of deionized water in dialysis has decreased the incidence of this form)

2. A sporadic endemic form whose cause remains unclear

3. A pediatric form that occurs in children with renal failure even when they have not yet undergone dialysis (this may be related to exposure to aluminum-containing medications)

Seizures in the ED should be treated with benzodiazepines; a serum aluminum level should be obtained in addition to performance of other standard laboratory tests if dialysis dementia is suspected (see Table 116.1).

Peritoneal Dialysis

Structure and Function

PD can be performed in a number of different ways; however, the complications associated with the various methods are similar. Typically, PD is performed with a Tenckhoff catheter (it can be straight or curved, single or dual cuffed) inserted in a median or paramedian line with or without omentectomy. Omentectomy is associated with fewer complications. The dialysate is infused into the abdomen via either a pump or gravity. It remains in the abdomen for a period, known as the dwell time, long enough to allow osmosis and diffusion. The effluent (or dialysate after dwelling in the abdomen) is then drained (Fig. 116.4).9

Complications

Complications of PD are organized into three groups: mechanical, infectious, and medical (Box 116.1).

Peritonitis is usually the most common finding in patients with PD catheter malfunction, but other problems can arise.1 Blood in the effluent suggests solid organ damage (especially if the catheter was placed recently), ruptured or leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm, or coagulopathy.

Medical Complications

Most frequently, medical complications are related to nutrition. Hypoalbuminemia results from poor dietary intake and daily loss of 15 g of protein, which promotes infection by impairing normal immune function. Hyperglycemia occurs as a result of a large glucose load in the dialysate. Bowel obstruction can occur secondary to abdominal surgery.10

Diagnostic Testing

Infectious Complications

Culture is critical when testing for infectious complications. PD-associated peritonitis is defined as two of the following three: (1) signs and symptoms; (2) white blood cell (WBC) count higher than 100/mL in the PD effluent, with more than 50% neutrophils after a dwell time of at least 2 hours; and (3) positive culture of an organism from the PD effluent.11 For patients undergoing automated PD who are being evaluated during their nighttime treatment, the dwell time will not be 2 hours, so the percentage of neutrophils should be used for diagnostic purposes even if the absolute WBC count is not higher than 100/mL. Bacteria in the peritoneal cavity have been diluted significantly by the dialysate, which can lead to negative cultures at standard volumes. To improve diagnostic results, 50 mL of effluent should be centrifuged down and the sediment resuspended in 3 to 5 mL of sterile saline before inoculation into both solid and liquid blood culture media. Alternatively, a minimum of 10 mL of effluent per blood culture bottle can be used. Blood cultures are not helpful unless the patient appears septic.12

Medical Complications

A comprehensive metabolic panel and serum lipase level should be obtained. Liver function tests and serum lipase levels can differentiate other causes of abdominal pain. Albumin levels are useful markers of malnutrition, which is present in 40% of these patients (25% of whom are severely malnourished). Hypoalbuminemia significantly increases the incidence of morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with peritonitis and those with a serum albumin concentration lower than 35 g/L. Hypokalemia causes decreased gut motility and constipation, which is associated with peritonitis; both conditions should be treated. Hyperglycemia, inadequate dialysis, and volume depletion or overload can be evaluated by physical examination and standard laboratory testing.10

Treatment

Mechanical Complications

For a clogged catheter, attempts to empty the bladder and then the bowel (with laxatives) may improve function. If the catheter is clogged with fibrin or clot, heparin (500 U/L) can be added to the dialysate. If this fails, urokinase can be used as a last resort (5000 IU diluted in saline), which has a success rate of 10% to 15%.9

In patients with catheter migration, kinking, dislodgment, and cuff extrusion, a one-time 2-g intravenous dose of ampicillin should be given for prophylaxis in the setting of tube manipulation.9

Infectious Complications

Gram-positive organisms account for three fourths of PD-associated infections, half of which are due to Staphylococcus epidermidis. Concerning organisms observed in infections are Pseudomonas, S. aureus (including MRSA), and fungal species.11

Intermittent or continuous antibiotic therapy can be used with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (Table 116.2). Dosing regimens are different for patients undergoing automated PD. For intermittent treatment, antibiotics are added to only one of the four daily exchanges. For continuous therapy, a loading dose is given in the first exchange and then a maintenance dose is given in each exchange for the remainder of the course of treatment.12

Table 116.2 Intraperitoneal Antibiotic Dosing Recommendations for Patients Undergoing Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis*

| ANTIBIOTIC | INTERMITTENT | CONTINUOUS† |

|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | ||

| Amikacin | 2 mg/kg | LD 25, MD 12 |

| Gentamicin, netilmicin, or tobramycin | 0.6 mg/kg | LD 8, MD 4 |

| Cephalosporins | ||

| Cefazolin, cephalothin, or cephradine | 15 mg/kg | LD 500, MD 125 |

| Cefepime | 1000 mg | LD 500, MD 125 |

| Ceftazidime | 1000-1500 mg | LD 500, MD 125 |

| Ceftizoxime | 1000 mg | LD 250, MD 125 |

| Penicillins | ||

| Amoxicillin | ND | LD 250-500, MD 50 |

| Ampicillin, oxacillin, or nafcillin | ND | MD 125 |

| Azlocillin | ND | LD 500, MD 250 |

| Penicillin G | ND | LD 50,000 units, MD 25,000 units |

| Quinolones | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | ND | LD 50, MD 25 |

| Others | ||

| Aztreonam | ND | LD 1000, MD 250 |

| Daptomycin | ND | LD 100, MD 20 |

| Linezolid | 200-300 mg/day orally | |

| Teicoplanin | 15 mg/kg | LD 400, MD 20 |

| Vancomycin | 15-30 mg/kg every 5-7 days | LD 1000, MD 25 |

| Antifungals | ||

| Amphotericin | NA | 1.5 mg/L |

| Fluconazole | 200 mg IP every 24-48 hr | |

| Combinations | ||

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 2 g every 12 hr | LD 1000, MD 100 |

| Imipenem-cilastin | 1 g bid | LD 250, MD 50 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 25 mg/L in alternate bags‡ | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 960 mg orally bid | |

bid, Two times per day; IP, intraperitoneally; LD, loading dose; MD, maintenance dose; NA, not applicable; ND, no data.

* For dosing of drugs with renal clearance in patients with residual renal function (defined as >100 mL/day of urine output), the dose should be empirically increased by 25%.

† Per exchange, once daily (mg/L; all exchanges).

‡ Given in conjunction with 500 mg intravenously twice daily.

One suggested regimen is cefazolin (15 mg/kg/day intraperitoneally [IP]) for intermittent treatment, or for continuous therapy administer a 500-mg loading dose with 125-mg maintenance doses. For gram-negative coverage, an antibiotic that also treats Pseudomonas infection should be given, such as ceftazidime (1000 to 1500 mg/day IP), or for continuous therapy use a 500-mg loading dose and 125-mg maintenance doses. If MRSA infection is suspected, vancomycin (15 to 30 mg/kg) can be added to the dialysate and should be used in place of cefazolin.12 Of note, vancomycin and ceftazidime must be mixed in a dialysate solution of greater than 1 L to be compatible. Aminoglycosides should not be mixed with penicillins in an intraperitoneal infusion.11

Doses for renally excreted drugs should be increased by 25% if the patient produces more than 100 mL of urine per day.12

Fungal infections may occur after antibiotic treatment. They require early removal of the catheter and are associated with a mortality of 25%.12

Exit site infections should be treated with oral antibiotics except in some cases of MRSA.11 Therapy is guided by Gram stain of the purulent drainage and by previous treatment regimens, although S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are responsible for the majority of infections. For first-time infections, immediate empiric antibiotic treatment of gram-positive organisms should be initiated (cephalexin, 500 mg orally two to three times daily). Suspected MRSA infections should be treated with vancomycin, clindamycin, Bactrim, or rifampin (do not use rifampin as monotherapy). Patients with MRSA infections may also be given intranasal and local mupirocin (cream, not ointment, because the polyethylene glycol in the ointment can damage the polyurethane in some PD catheters) twice a day for 5 to 7 days. Suspected pseudomonal infections should be treated with quinolones, although double therapy in accordance with local susceptibility patterns is recommended because of the rapid rise of resistance.11 The duration of treatment is at least 2 weeks for gram-positive organisms and 3 weeks for pseudomonal organisms.

Medical Complications

Management of most medical complications in PD patients is similar to that in the general population. Hyperglycemia can be treated with intraperitoneal insulin, but at higher doses.11 Hypokalemia should be treated aggressively because it leads to constipation and risk for peritonitis. Hypoalbuminemia should be managed with protein supplements and education of the patient. In severe cases, total parenteral nutrition or intravenous albumin (or both) may be necessary.10

Disposition

Infectious Complications

The majority of patients with peritonitis are stable and can be treated at home. Those with fever, vomiting, intractable pain, fungal infection, or concomitant catheter site infection and those refractory to outpatient treatment require hospital admission. Discharge and urgent follow-up should be arranged with the team that placed the catheter and with the patient’s nephrologist.1

Himmelfarb J. Hemodialysis complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:1122–1131.

Nassar GM, Ayus JC. Infectious complications of the hemodialysis access. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1–13.

Padberg FT, Calligaro KD, Sidawy AN. Complications of arteriovenous hemodialysis access: recognition and management. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:55S–80S.

1 Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, et al. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(1 Suppl 1):e1–526. A8

2 Nassar GM, Ayus JC. Infectious complications of the hemodialysis access. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1–13.

3 Lok CE, Mokrzycki MH. Prevention and management of catheter-related infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney International advance online publication. 2011;79:587–598.

4 Padberg FT, Calligaro KD, Sidawy AN. Complications of arteriovenous hemodialysis access: recognition and management. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:55S–80S.

5 Sofocleous CT, Hinrichs CR, Weiss SH, et al. Alteplase for hemodialysis access graft thrombolysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:775–784.

6 Ebo DG, Bosmans JL, Couttenye MM, et al. Haemodialysis-associated anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions. Allergy. 2006;61:211–220.

7 Arieff AI. Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome: current concepts on pathogenesis and prevention. Kidney Int. 1994;45:29–35.

8 Himmelfarb J. Hemodialysis complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:1122–1131.

9 Bhatla B, Khanna R, Twardowski ZJ. Peritoneal access. J Postgrad Med. 1994;40:170–178.

10 Gokal R, Mellnick NP. Peritoneal dialysis. Lancet. 1999;353:823–828.

11 Li PK-T, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30:393–423.

12 Dasgupta MK. Management of patients with type 2 diabetes on peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2005;21:120–122.