CHAPTER 45 DIAGNOSTIC PERITONEAL LAVAGE AND LAPAROSCOPY IN EVALUATION OF ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

Before 1965, lavage of the peritoneal cavity had a recognized role for the diagnosis and treatment of acute peritonitis, treatment of chronic renal failure, and treatment of drug overdosage. In 1965, Root published a landmark article describing the use of peritoneal lavage to diagnose occult intra-abdominal hemorrhage in 28 patients. Lavage of the abdominal cavity with 1 liter of an isotonic solution dramatically improved the sensitivity for detecting intra-abdominal hemorrhage compared with four quadrant paracentesis, which carried false negative rates of 17%–36%. In the period before 1965, blunt abdominal trauma mortality was over 45%, with two-thirds of deaths attributed to undiagnosed intra-abdominal hemorrhage or visceral injury. Root established the basic principles pertaining to diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) that would be followed for over 20 years. These include controlling skin bleeding before catheter insertion to reduce contamination of the fluid, attempting aspiration of free blood before infusing fluid, mild rocking of the patient to improve the chance of a mixed sample, retrieving a large proportion of the infusate, and examining the lavage fluid for hemoglobin concentration, amylase, and bacteria. Root did not specify criteria for hemoglobin concentration or cell counts, but noted the subjective criterion of “more than a faint salmon pink tinge of blood in the retrieved perfusate is an indication of intra-peritoneal hemorrhage requiring laparotomy….” He noted the excellent sensitivity and found no false positives, but one case was reported as a possible complication because an isolated bowel perforation was encountered.

From 1966 to September 2005, there were 2445 Medline-indexed articles, which referred to “peritoneal lavage” as a medical subject heading (MESH) or in the title or abstract. Of these, 931 articles also map to the MESH term “wounds and injuries,” or mention “trauma” in the title or abstract. After eliminating review articles and those that do not pertain to humans, 791 remained that relate to diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the context of trauma. There are no randomized prospective clinical trials comparing DPL to other diagnostic maneuvers. However, there are nine randomized clinical trials comparing at least two distinct DPL techniques. While the transitions are indistinct, some generalizations can be made about observable patterns in the literature. Publications in the first decade following Root’s article consisted mainly of case reports and case series showing the adoption of DPL as a diagnostic maneuver for blunt abdominal trauma. The second decade (1976–1985) brought larger case series, describing variations in technique, defined specific criteria for a positive lavage, and compared DPL to computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound (US) for diagnosing abdominal injury. During this period, DPL was regarded as the gold standard to which developing technologies were compared. Comparisons were not randomized, but based on selection by hemodynamic stability. Many studies used a cross-over design, where patients underwent two studies and the results were compared. By the third decade (1986–1995), CT scanning emerged as the preferred modality for diagnosing traumatic abdominal injuries. US was being evaluated as a viable and less invasive substitute for DPL, and DPL was mentioned passively, predominantly as one of several modalities by which abdominal injuries were being diagnosed in larger retrospective series. Of the 205 articles mentioning DPL since 1996, only 42 were coded as having a focus on the subject. Seven of these pertain to an article and six comments entitled “Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage—An Obituary.” Despite the implications of the article, there remains support for a limited role for DPL in trauma.

Options for diagnostic evaluation of the ambiguous abdomen include serial clinical exam, DPL, US, and CT. Clinical exam is notoriously unreliable, particularly when confounded by distracting injuries and altered sensorium resulting from intoxication, head injury, or both. Serial exam and repeat hemoglobin measurement continues to be a viable approach for stable, alert patients, with a low suspicion for abdominal injury. Some advocate a more definitive objective evaluation for the sake of shortening hospital stay and reducing resource utilization. DPL emerged as the standard for resolving the ambiguous abdominal exam. Its primary advantages and disadvantages are noted in Table 1. When considered as a diagnostic tool for hemoperitoneum, DPL is highly sensitive, specific, and accurate. However, according to current concepts in the management of abdominal trauma, hemoperitoneum alone does not constitute an indication for operative exploration. Thus, DPL is too sensitive and leads to a high incidence of nontherapeutic laparotomy. When used to indicate the need for laparotomy, the specificity is low and accuracy is limited. Given that low-grade splenic and hepatic injuries are the most common cause of hemoperitoneum after blunt trauma, and that most of these can be successfully managed nonoperatively, DPL has been largely replaced by focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) and CT as the preferred diagnostic modalities by which therapeutic decisions are made.

Table 1 Primary Advantages and Disadvantages of DPL

| Advantages of DPL | Disadvantages of DPL |

|---|---|

| Rapid to perform | Potential for inadequate exam |

| Relatively easy to teach | Potential to produce visceral injury |

| Does not require high technology | Requires element of training and skill |

| Highly sensitive for hemoperitoneum | Oversensitive for hemoperitoneum leading to high rate of nontherapeutic laparotomy |

| Highly specific for hemoperitoneum | |

| Can detect hollow viscus injury | May miss retroperitoneal injuries |

| Can be used for blunt or penetrating injuries | May lead to rupture and decompression of retroperitoneal hematoma |

| Can be performed in emergency room or operating room during other emergency procedures |

DPL, Diagnostic peritoneal lavage.

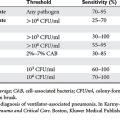

In an effort to refine the diagnostic value of DPL, attention was directed toward microscopic examination of lavage fluid. Rather than merely characterizing the color of the fluid as “salmon pink,” the inability to “read newsprint” through the fluid was used as a predictive criteria. This evolved into the use of automated cell counts with varying thresholds. Greater than 100,000 red blood cells per cubic millimeter of lavage fluid or greater than 500 white blood cells per cubic millimeter became commonly accepted as an indication for abdominal exploration following blunt injury. By these criteria, Nagy achieved a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 96% for 2500 patients. However, like much of the literature pertaining to DPL, the incidence of nontherapeutic laparotomy is not reported. Although the criteria are variable, nontherapeutic laparotomy rates associated with DPL are reported as high as 36%. In cases of penetrating trauma, a lower red cell count, 10,000/mm3–50,000/mm3, are used as criteria to establish penetration of the abdominal wall. A similar dilemma exists regarding the incidence of nontherapeutic laparotomy, because penetration is not always accompanied by visceral perforation. For both blunt and penetrating trauma, if one accepts that the amount of blood in the peritoneal cavity is proportional to the severity of the injury, then an inverse relationship can be predicted between the quantified cell counts and the likelihood of nontherapeutic laparotomy. If one lowers the threshold to designate DPL as positive, then the sensitivity for hemoperitoneum will be high, but the incidence of nontherapeutic operations will rise.

LAPAROSCOPY IN TRAUMA

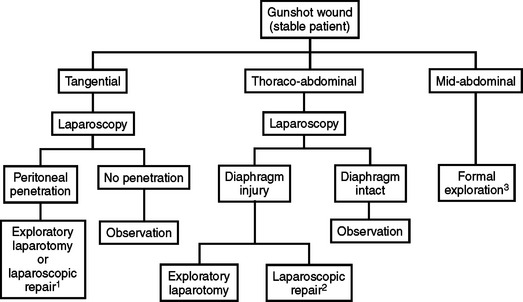

Sound surgical judgment must be used in choosing patients for laparoscopic evaluation after injury. Any injured patient with hemodynamic instability or obvious complex intra-abdominal injury, is not a candidate for laparoscopy, but instead requires immediate laparotomy. Several large series performed by experienced groups have demonstrated that only about 15% of patients with suspected intra-abdominal injury are reasonable candidates for adjunctive laparoscopic evaluation or treatment. For patients with gunshot wounds to the abdomen, laparoscopy has proved most useful for evaluation of the diaphragm in patients with thoracoabdominal wounds (Figure 1). In addition, laparoscopy has proven useful to determine if peritoneal penetration has occurred from tangential gunshot wounds or stab wounds.

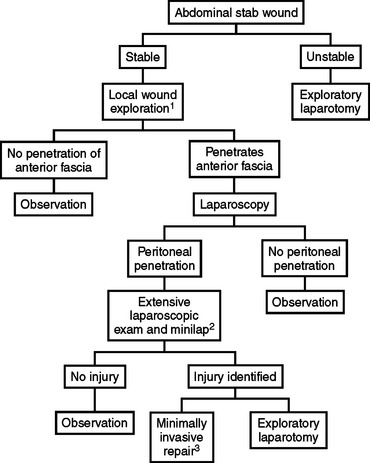

Victims of stab wounds are somewhat more likely to benefit from laparoscopic examination (Figure 2). In this group of patients, as many as 50% will not have significant intra-abdominal injury. Laparoscopy can be used to reduce the number of negative and nontherapeutic laparotomies in patients with minimal injuries. Laparoscopic repair of small diaphragmatic injures and limited hollow viscus injuries secondary to stab wounds has been reported in the literature and appears to be a viable technique in the hands of a skilled laparoscopic surgeon. The use of laparoscopy in most trauma centers has been associated with a small decrease in the incidence of negative and nontherapeutic laparotomy.

A very small percentage of patients with blunt abdominal trauma may benefit from laparoscopic evaluation. Previous reports using laparoscopy for the examination of hepatic and splenic lacerations are not pertinent at this time. The increasing trend toward nonoperative treatment of these injuries and the emergence of arteriography and embolization has made this approach to solid organ injury less viable. An area of potential benefit in the blunt trauma setting is examination of the entire small bowel and colon in a patient at risk for the so-called “seat-belt” syndrome. With moderately developed laparoscopic skills, the vast majority of the small bowel and colon can be examined with laparoscopic techniques. Large injuries to hollow viscera are easily detected; however, small enterotomies may still be missed. Therefore, a very low threshold for conversion to laparotomy must be maintained in the patient at risk for hollow viscus injury. Unfortunately, the literature does not clearly delineate or document the efficacy of laparoscopy in the blunt trauma setting.

Adkinson C, Roller B, Clinton J, Ruiz E, Bretzke M. A comparison of open peritoneal lavage with modified closed peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):352-356.

Bain IM, Kirby RM, Tiwari P, McCaig J, Cook AL, Oakley PA, Templeton J, Braithwaite M. Survey of abdominal ultrasound and diagnostic peritoneal lavage for suspected intra-abdominal injury following blunt trauma. Injury. 1998;29(1):65-71.

Bowyer CM, Liu AV, Bonar JP. Validation of SimPL—a simulator for diagnostic peritoneal lavage training. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;111:64-67.

Brams DM, Cardoza MD, Smith RS. Laparoscopic repair of a traumatic gastric perforation using a gasless technique. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3:587-591.

Brown GRJr, Burnett WE. Evaluation of peritoneal lavage in the treatment of severe, diffuse peritonitis. Surg Forum. 1957;7:166-168.

Cochran W, Sobat WS. Open versus closed diagnostic peritoneal lavage. A multiphasic prospective randomized comparison. Ann Surg. 1984;200(1):24-28.

Cue JI, Miller FB, Cryer HM3rd, Malangoni MA, Richardson JD. A prospective, randomized comparison between open and closed peritoneal lavage techniques. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 1990;30(7):880-883.

DeMaria EJ. Management of patients with indeterminate diagnostic peritoneal lavage results following blunt trauma. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 1991;31(12):1627-1631.

Esposito TJ. Laparoscopy in blunt trauma. Trauma Q. 1993;10:260-272.

Fabian TC, Croce MA, Stewart RM, Pritchard FE, Minard G, Kudsk KA. A prospective analysis of diagnostic laparoscopy in trauma. Ann Surg. 1993;217:557-565.

Fang JF, Chen RJ, Lin BC. Cell count ratio: new criterion of diagnostic peritoneal lavage for detection of hollow organ perforation. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 1998;45(3):540-544.

Felice PR, Morgan AS, Becker DR. A prospective randomized study evaluating periumbilical versus infraumbilical peritoneal lavage: a preliminary report. A combined hospital study. Am Surg. 1987;53(9):518-520.

Fryer JP, Graham TL, Fong HM, Burns CM. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage as an indicator for therapeutic surgery. Can J Surg. 1991;34(5):471-476.

Gou DY, Jin Y, Chen LY, Wei Q. ICU management of patients with suspected positive findings of diagnostic peritoneal lavage following blunt abdominal trauma. Chin J Traumatol. 2005;8(1):46-48.

Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. A critical evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34:822-828.

Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. Selective celiotomy for missile wounds of the abdomen based on laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:366-370.

Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Weksler B, Bayard V, Stahl WM. Laparoscopy in the evaluation of the intrathoracic abdomen after penetrating injury. J Trauma. 1992;33:101-109.

James JA, Kimbell L, Read WT. Experimental salicylate intoxication. I. Comparison of exchange transfusion, intermittent peritoneal lavage, and hemodialysis as means for removing salicylate. Pediatrics. 1962;29:442-447.

Jansen JO, Logie JR. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage—an obituary. Br J Surg. 2008;92(5):517-518.

Lopez-Viego MA, Mickel TJ, Weigelt JA. Open versus closed diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the evaluation of abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 1990;160(6):594-596. discussion 596–597

Moore JB, Moore EE, Markovchick V, Rosen P. Peritoneal lavage in abdominal trauma: a prospective study comparing the peritoneal dialysis catheter with the intracatheter. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9(4):190-192.

Nagy KK, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, An GC, Bokhari F, Barrett J. Experience with over 2500 diagnostic peritoneal lavages. Injury. 2000;31(7):479-482.

Perry JFJr. A five-year survey of 152 acute abdominal injuries. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 1965;147:53-61.

Root HD, Hauser CW, McKinley CR, Lafave JW, Mendiola RPJr. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Surgery. 1965;57:633-637.

Sicilia LS, Barber ND, Mulinari AS, Kolff WJ. Automatic device for peritoneal lavage in chronic renal failure. Ohio State Med J. 1964;60:839-843.

Smith RS, Fry WR. Alternative techniques in laparoscopy for trauma. Trauma Q. 1994;10:291-300.

Smith RS, Fry WR, Morabito DJ, Koehler RH, Organ CHJr. Therapeutic laparoscopy in trauma. Am J Surg. 1995;170:632-637.

Smith RS, Fry WR, Tsoi EK, et al. Gasless laparoscopy and conventional instruments: the next phase of minimally invasive surgery. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1102-1107.

Smith RS, Meister RK, Tsoi EKM, Bohman HR. Laparoscopically-guided blood salvage and autotransfusion in splenic trauma: a case report. J Trauma. 1993;34:313-314.

Stengel D, Bauwens K, Sehouli J, Rademacher G, Mutze S, Ekkernkamp A, Porzsolt F. Emergency ultrasound-based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004446.

Troop B, Fabian T, Alsup B, Kudsk K. Randomized, prospective comparison of open and closed peritoneal lavage for abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(12):1290-1292.

Wilson WR, Schwarcz TH, Pilcher DB. A prospective randomized trial of the Lazarus-Nelson vs. the standard peritoneal dialysis catheter for peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 1987;27(10):1177-1180.

Zantut LF, Ivatury RR, Smith RS, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for penetrating abdominal trauma: a multicenter experience. J Trauma. 1997;42:825-831.

Zantut LF, Rodrigues AJ, Birolini D. Laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of trauma. Pan Am J Trauma. 1990;2:6.