Diagnostic Cytology of the Liver

Aileen Wee

Martha Bishop Pitman

Introduction

As the role of fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) in the evaluation of focal liver lesions has evolved, it has presented new challenges.1,2 Advances in dynamic imaging modalities have obviated the need for tissue confirmation in clinically classic cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).3–12 Ultrasound surveillance and serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) assessment of high-risk patients have improved the detection of small nodules (≤2 cm in diameter).13–16 Accurate cytohistologic characterization of small, well-differentiated hepatocellular nodules on limited tissue samples is extremely challenging, but it has important therapeutic implications.

Much progress has been made in the molecular characterization of tumors by genomic, microRNA, and proteomic methods. There are promising new tools for tumor diagnosis, for predicting the prognosis and progression of disease, and for personalized, molecularly targeted anticancer therapies and chemopreventive strategies.17–26 Because FNAB is the least invasive tool for tissue procurement, it is predicted that it will become a point of care in the management algorithm of HCC for diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostication purposes.27

Use of Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy

Guidance Systems

Percutaneous (transabdominal) FNAB performed under ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) guidance is a safe, efficacious, and cost-effective outpatient procedure for the diagnosis of focal liver lesions.28–30 Aspiration can also be performed during laparotomy or laparoscopy under palpation or direct vision. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA (EUS-FNA) is the latest diagnostic and staging tool and is used primarily for left hepatic lobe lesions and hilar or perihilar masses, in which the needle traverses the wall of the gastrointestinal tract.31 Factors influencing the choice of guidance system include the size and location of the lesion, operator expertise and preference, and availability of imaging technologies.27–29

Ultrasound provides rapid localization, flexible patient positioning, and imaging of the lesion without radiation. It is typically used for initial guidance, particularly when there are multiple lesions or large, relatively superficial lesions. CT allows optimal resolution of small lesions or lesions not visible with ultrasound, accurate localization of the needle tip immediately before sampling, improved definition of tissue components and vascularity, and more precise demonstration of the anatomic relationships of a given lesion.

EUS-FNA is a safe, accurate, and versatile technique, but it is highly operator dependent.32–36 It allows concurrent sampling of pancreas and liver lesions, which can confirm primary and metastatic lesions in one diagnostic encounter. The technique is useful for small and deep-seated left lobe lesions that are below CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) resolution or lesions that are not easily accessible by percutaneous FNAB. It improves staging of liver metastases, is good for early detection of multifocal HCC in cirrhosis, and can assess the accurate number of lesions (e.g., intrahepatic staging of HCC) for transplantation eligibility.37,38

Percutaneous FNAB techniques include individual puncture, coaxial biopsy, and tandem needle biopsy techniques.39 Multiple aspirations (as many as four passes) usually can be performed with minimal morbidity. The needle size is between 20 and 22 gauge. Aspiration needles with a guillotine mechanism enable microbiopsy cores to be procured at the same sitting. Concomitant core-needle (18-gauge) biopsies may also be performed.

Indications and Contraindications

FNAB is the diagnostic procedure of choice for focal liver lesions, especially to confirm a suspected malignancy (Box 45.1). It is particularly advantageous for advanced malignancies and patients who are poor surgical candidates. Another indication is drainage of a cyst or abscess for culture and therapeutic ablation.40 Early affirmative diagnosis leads to cost savings in terms of further investigational tests and hospitalization.

Contraindications for percutaneous FNAB include an uncorrectable bleeding diathesis, lack of a safe access route (i.e., biopsy through a vascular structure), and an uncooperative patient for whom awkward positioning or maintenance of strict breath control is necessary to ensure proper needle placement.28 For EUS-FNA, gastrointestinal obstruction is an absolute contraindication resulting from the risk of perforation.34

Complications

Complications of FNAB are uncommon.39 There may be bleeding, which is mostly associated with severe cirrhosis and coagulopathy but may relate to the size of needle used, particularly in vascular lesions and in large superficial tumors not covered by normal parenchyma (see Box 45.1).12 Needle tract seeding is rare, with an incidence of 0.003% to 0.009% for malignancy in general and 0.003% to 5% for HCC; if a small (22-gauge), noncutting needle is used, the rate for HCC is approximately 0.11%.11,41–44 A higher incidence of HCC recurrence in the transplanted liver has been reported in transplantation cases with preoperative FNAB.45 Death, usually resulting from bleeding, is rare, with a reported mortality rate of 0.018%.42

Clinical Considerations

There is much debate regarding the use of preoperative FNAB for the diagnosis of HCC.27 Several reasons are cited46–48 for opposing FNAB:

• Advances in dynamic imaging modalities that are sufficiently sensitive for establishing an HCC diagnosis3,8,10,11,49

• Risk of needle tract seeding11,41–44,50

• Risk of intraperitoneal bleeding12

• Risk of intraprocedural hematogenous dissemination, which results in a higher incidence of tumor and posttransplantation recurrence41,45

• Adoption of a wait and see policy for hepatocellular nodules that are less than 1 cm in diameter4,5

• Indeterminate cytohistologic reports rendered for well-differentiated hepatocellular nodules51,52

Several reasons are cited53,54 for favoring FNAB:

• Serum AFP has a low sensitivity (<50%)55,56

• Use of the coaxial biopsy technique to reduce the risk of seeding57

• Decreased costs of long-term imaging surveillance

• Avoiding futile transplantation in false-positive imaging cases7

• Allaying patient anxiety after a liver nodule has been detected on imaging

• Confirmation of HCC that increases eligibility for liver transplantation

• Immediate institution of anti-HCC therapy when the lesion is less than 2 cm in diameter

According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 2000 Conference and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) guidelines, nodules more than 2 cm in diameter in cirrhotic livers are diagnosed as HCC if they show an intense arterial profile with contrast washout in delayed venous phase on one dynamic imaging modality.4,5 Nodules between 1 and 2 cm in cirrhotic livers require concurrence of two coincidental imaging modalities; otherwise, biopsy is recommended.49 For nodules less than 1 cm in diameter, the EASL guidelines recommend a wait and see policy with surveillance every 3 months. Approximately 68% of nodules less than 1 cm in diameter in cirrhotic livers are HCCs.58 In skilled hands and with an expert reader, ultrasound-guided FNAB of hepatic nodules less than 1 cm in diameter can yield correct diagnoses in 90% of cases.41 The conundrum is to balance the risk of unnecessary surgery (2.5%) against the risk of seeding.9,11,53,54

Specimen Preparation

The types of small tissue samples from liver FNAB include direct smears, needle rinses, core imprints, cell blocks, microbiopsies, and core-needle biopsies. Smears may be air-dried and stained with Diff-Quik or May-Grünwald-Giemsa or fixed in 95% alcohol and stained by the Papanicolaou method. Rapid touch preparations (imprints) can be performed to assess the adequacy of tissue cores.59 If well-fixed, adequately smeared slides are difficult to obtain, the aspirate can be expressed into a preservative and submitted as a liquid-based specimen for processing by the ThinPrep or SurePath method.

Cell blocks are made from needle rinses and tissue fragments.60,61 Particulate material should be quickly retrieved from the glass slides before staining for subsequent formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cell block preparation. Histologic sections allow for architectural appraisal, special stains, and immunohistochemistry. Immunocytochemistry may be necessary if only smears are available.

Diagnostic Accuracy

The prerequisites for optimal results with FNAB are listed in Box 45.2. The sensitivity of FNAB varies according to the method used (i.e., blind versus guided aspiration, number of passes, and operator skill), characteristics of the lesion (size, location, and consistency), and standard of cytopathology service (e.g., quality of smears, combined cytohistologic analysis, ancillary testing, reader expertise).61–63 On-site cytology service may provide rapidly stained smears for evaluation of sample adequacy, retrieval of particulate material for cell block preparation, and triage of specimens for culture, flow cytometry, electron microscopy, and other ancillary tests, including molecular studies.60,64,65 In the absence of an on-site service, it is imperative that the aspirator learns how to make proper smears and that a tissue management protocol is clearly understood by the patient care team.

The sensitivity and specificity of percutaneous FNAB for detection of liver malignancy are about 90% (range, 67% to 100%) and 100%, respectively.12,66,67 The positive and negative predictive values and overall accuracy of FNAB diagnosis for liver malignancy were reported in one large study to be 100%, 59.1%, and 92.4%, respectively.12 EUS-FNA also has a high sensitivity (82% to 94%) and specificity (90% to 100%) for malignancy.32,33,35,36 Similar to percutaneous FNAB, EUS-FNA leads to a better diagnostic yield with metastases compared with well-differentiated hepatocellular tumor nodules. False positives are rare. False-negative diagnoses are most often the result of a sampling error because of inexact needle localization related to small masses, large areas of necrosis, fibrosis, or a prominent inflammatory rim. The supplemental nature of FNAB and concomitant core-needle biopsy improve overall accuracy, especially for benign neoplasms and poorly differentiated neoplasms that require ancillary studies.63,68

Liquid-based cytology of liver aspirates shows good correlation with conventional smears and reduces false-negative diagnoses.69–71 Advantages include more representative sampling and better cell preservation. Disadvantages include no on-site assessment of adequacy or triage of specimens, no air-dried smears for Giemsa preparations, removal of background elements, high cost, and the need for familiarity with cytologic artifacts and recognition of diagnostic pitfalls to avoid misinterpretations. In our experience (unpublished data) with the ThinPrep method, the cytologic features of HCC appear to be rather nondifferentiated.1 Cytoarchitectural features, such as arborizing trabecular structures, pseudoacinar rosettes, and peripheral or transgressing endothelium, are less evident or completely lost. Tumor aggregates tend to be tighter, three dimensional, and smaller. Cells are usually smaller with nondescript shapes and denser cytoplasm, and they often have frayed borders.

Diagnostic Issues

Focal liver lesions range from cystic and inflammatory or infectious entities to benign or malignant primary and metastatic neoplasms. HCC is well known for its heterogeneity. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CC) frequently shows nondescript features of adenocarcinoma. The liver is a common depository for metastases. Given these permutations, primary liver carcinomas can mimic many tumors and vice versa. The diagnostic issues are listed in Box 45.3.

Integrative Approach to the Evaluation of Liver Aspirates

A stepwise algorithmic approach to evaluating liver aspirates includes full clinicopathologic correlations61,65,72 (Box 45.4):

1. Evaluate clinical information. A patient may be seen with one or more focal liver lesions in the following scenarios: routine medical checkup, screening or surveillance of chronic liver disease,13,16 follow-up of a known cancer case, investigation of a symptomatic patient, or investigation of a pediatric lesion. Relevant clinical findings, liver function profile, serology, and tumor markers should be obtained.21,55,56

2. Evaluate radiologic information. Focal liver lesions may be cystic or solid and single or multiple. The presence of preexisting or chronic hepatobiliary disease and associated radiologic findings should be determined. Advances in dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging modalities have increased the sensitivity and specificity for detection of classic HCC.3,8,10 Siderotic nodules are readily detected on T2- or T2*-weighted MRI.73,74

3. Evaluate cytohistologic findings. The smears are scanned at low power to establish the pattern and architecture before close inspection of cellular details as listed in Box 45.5. The operator should ascertain whether the lesion is (1) cystic (true cyst or pseudocyst) and benign or malignant or (2) solid (hepatocellular or nonhepatocellular) and benign or malignant. The diagnostic algorithms for evaluation of cystic and solid lesions of the liver are provided in Boxes 45.6 and 45.7, respectively.75

Cytohistology of the Liver

Normal Morphology

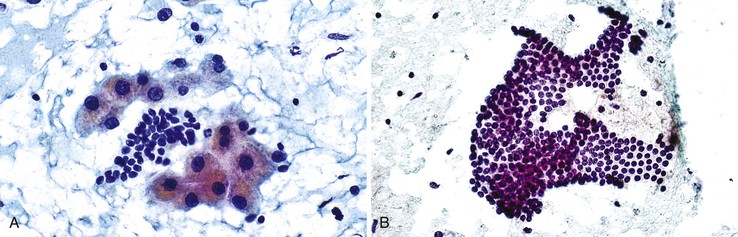

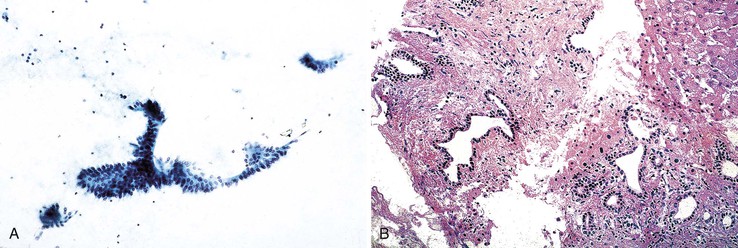

Aspirate smears of normal liver typically show a polymorphous cell population dominated by hepatocytes, occurring singly in short rows or small clusters and intermingling with scattered bile duct epithelial cells and sparse sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells (Fig. 45.1, A). Normal hepatocytes are large, polygonal cells with abundant granular cytoplasm and a centrally placed, round nucleus with a well-delineated nuclear membrane, granular chromatin pattern, and distinct nucleolus. Hepatocytes normally exhibit variations in cell and nuclear size (i.e., sibling polymorphism). The nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio (N : C ratio) is approximately 1 : 3. Bile duct epithelial cells are smaller than hepatocytes and appear as flat, monolayered, honeycomb sheets of glandular epithelium (see Fig. 45.1, B). They may also reveal an on-edge picket-fence arrangement or small acinar structures. The cells have minimal pale cytoplasm and equidistant, round to oval, bland nuclei without nucleoli. Bile duct epithelium can be differentiated from bile ductular epithelium.

Elongated endothelial cells and comma-shaped Kupffer cells are almost indistinguishable from each other, especially when they appear as nuclear streaks. The thickness of liver cords can be appreciated in large sheets of cells and in fragments of liver parenchyma by focusing on the nuclear streaks in different planes of magnification (Fig. 45.2).

Pigments

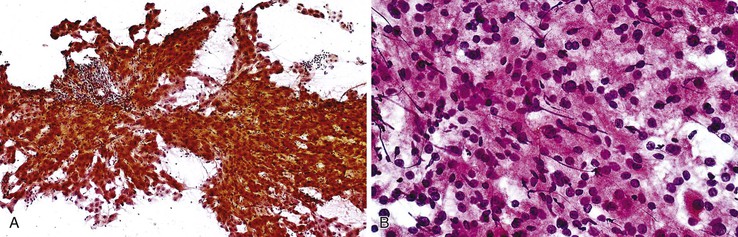

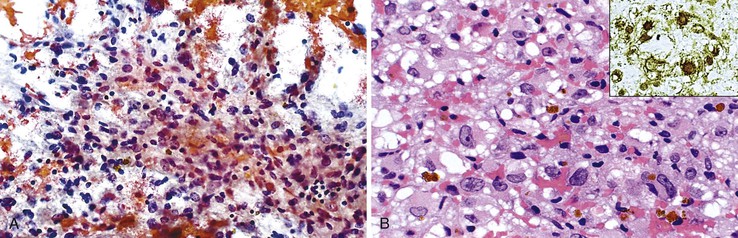

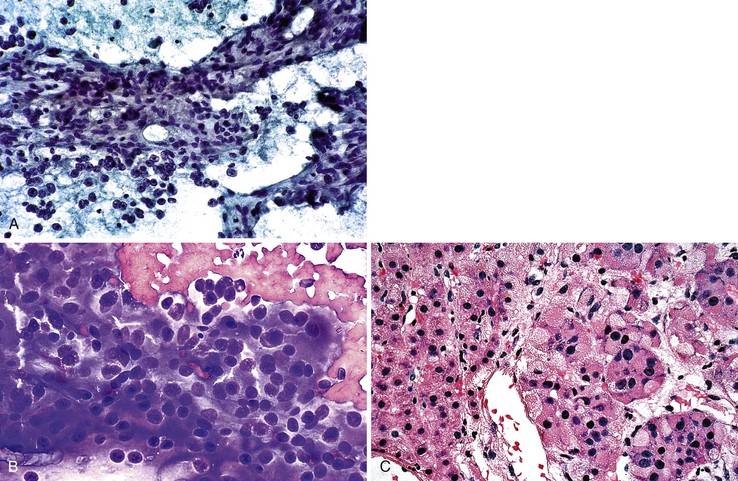

Lipofuscin is a fine, golden, granular, relatively nonrefractile pigment with Papanicolaou stain and is black with Giemsa stain (Fig. 45.3). This predominantly perinuclear pigment is common in aspirates of adult livers, and its absence in the context of a mass lesion is considered suspicious for a hepatocellular neoplasm. One potential diagnostic pitfall is that lipofuscin stains similar to melanin with Fontana-Masson stain, and the sample may be mistaken for metastatic melanoma.76

Bile pigment varies in color, texture, size, and density, but it is best recognized by its coarse, irregular, rather amorphous, nonrefractile appearance. In Giemsa-stained preparations, bile appears as a purplish-black pigment within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes or as ropey strands within bile canaliculi (Fig. 45.4). Hall stain may be used to confirm the pigment as bile.

Iron or hemosiderin may be present in hepatocytes, bile duct epithelial cells, and Kupffer cells as a coarse, golden-brown, refractile pigment with the Papanicolaou stain and brown-black with the Giemsa stain (Fig. 45.5). Malignant hepatocytes typically lose their ability to retain iron. In the setting of hemochromatosis, Perl (Prussian blue) stain is a helpful ancillary tool to highlight nonstaining tumor cells.77,78

Steatosis

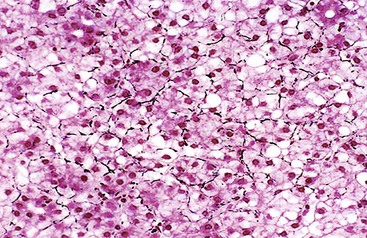

Steatosis is common in the liver, and the examiner should be aware of focal fatty changes.79,80 Cytologically, fat may be a single, large, intracytoplasmic vacuole in a cell with an eccentric nucleus (i.e., macrovesicular steatosis) or multiple, small vacuoles in a cell with a central nucleus (i.e., microvesicular steatosis) (Fig. 45.6). Fat is best appreciated in Giemsa-stained preparations, which often reveal abundant oil globules in the background as a result of ruptured hepatocytes.

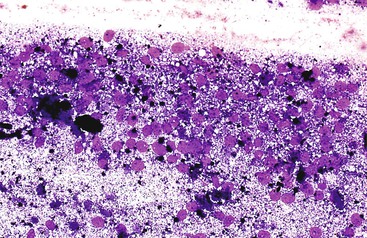

Infections

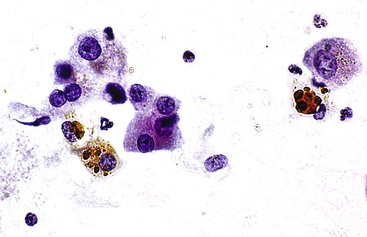

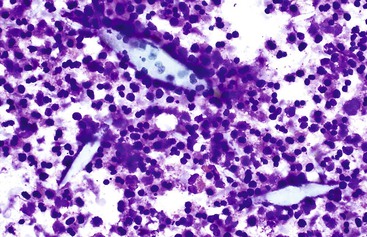

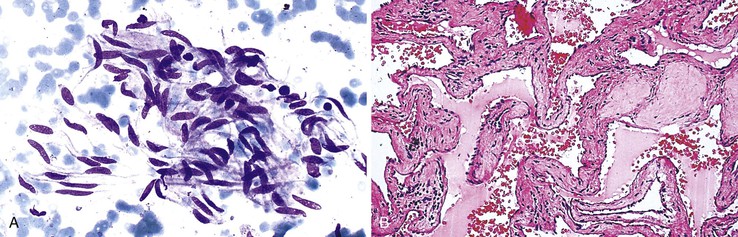

Liver abscess formations are suspected radiologically by the characteristic double target sign on CT scans.81 The most common is pyogenic abscess, in which case aspiration is performed for tissue confirmation, culture, and drainage.82,83 Smears are dominated by acute inflammatory cells and cellular debris (Fig. 45.7). Cultures are helpful for identification of bacterial organisms. Special stains, such as Gram stain, are not usually helpful, but uniquely characteristic organisms may be readily identified on smears. For example, Actinomyces has sulfur granules (Fig. 45.8).

Smears from suspected fungal abscesses should be stained with Gomori methenamine silver and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains. Amebic abscesses tend to be paucicellular with abundant amorphous granular debris, and trophozoites are rare. Necrotizing eosinophilic granulomas contain abundant eosinophils and possibly Charcot-Leyden crystals. Parasitic or fungal organisms should be sought (Fig. 45.9).

A potential diagnostic pitfall is that necrotic tumors may be associated with fever, simulating abscesses clinically and radiologically;84 or they may become secondarily infected. If clinically warranted, aspiration cytology is recommended to avoid delay in instituting appropriate therapy.

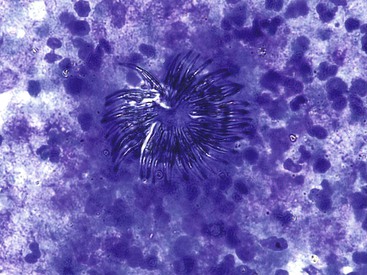

Hydatid disease leads to cyst formation, which may become secondarily infected (see “Cystic Lesions of the Liver”). Echinococcosis is usually ruled out with clinical and imaging studies and the findings of a negative test result for specific echinococcal antibodies by serum enzyme immunosorbent assay performed before percutaneous needle aspiration.85,86 In the event that a hydatid cyst is aspirated, the pathologist should search for protoscolices or hooklets of Echinococcus granulosus in the fluid or pus (Fig. 45.10).

Granulomatous inflammation may be caused by fungal or acid-fast organisms, but the presence of granulomas is not necessarily diagnostic of an infection. Cytologically, granulomas are composed of clusters of epithelioid histiocytes that have oval to elongated, sometimes twisted nuclei and visible but indistinct cytoplasm. Multinucleated giant cells may be present (Fig. 45.11). The characteristics of the necrotic background should also be evaluated. Gomori methenamine silver, PAS, and Ziehl-Neelsen stains may be performed on smears but are easier to perform on tissue sections.

Inflammatory pseudotumors are potential clinical, radiologic, and cytohistologic pitfalls because they mimic tumors. They may be lymphoplasmacytic, fibrohistiocytic, xanthogranulomatous, or granulomatous in nature (Fig. 45.12).87–90 Activated lymphoid cells may be mistaken for lymphomas, atypical reactive hepatocytes for HCC, atypical reactive biliary epithelium for adenocarcinoma, atypical reactive stroma for sarcoma, and foamy histiocytes for amebic trophozoites. Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)–related disease may rarely manifest as a fibroblastic mass with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, eosinophils, IgG4-positive plasma cells, dense fibrosis of large bile ducts, and obliterative phlebitis.91

Nodular hematopoiesis is a rare diagnostic pitfall. Hematopoietic cells (especially megakaryocytes) may mimic inflammatory or malignant cells when perceived out of context.92,93

Cystic Lesions of the Liver

The type of cyst contents should be evaluated because the presence of mucin is a helpful diagnostic clue. The next step is to establish the presence and type of epithelial lining and whether it is neoplastic or malignant.94 Box 45.6 provides a diagnostic algorithm for cystic lesions of the liver.

Cystic Lesions with an Epithelial Lining

Bile Duct Cyst, Simple Hepatic Cyst, and Fibropolycystic Disease

In cases of bile duct cyst, simple hepatic cyst, and fibropolycystic disease, the fluid may contain isolated cells or scant strips or sheets of cuboidal to low columnar epithelium without cytologic atypia (Fig. 45.13).

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm and Intraductal Papillary Neoplasm

Mucinous cystic neoplasms and intraductal papillary neoplasms have overlapping cytomorphologic features. The cytodiagnosis may indicate a benign cyst, papillary neoplasm, or adenocarcinoma. FNAB alone cannot differentiate the various types of hepatobiliary cysts.94,98 Generic terms such as cystic mucinous neoplasm or neoplastic mucinous cyst may be applied if imaging studies are not available for correlation.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms typically occur as single or multiloculated, mucinous, epithelial-lined cysts surrounded by ovarian-type stroma.99 The cyst fluid may be watery or viscous. Diagnostic aspirates likely contain degenerated cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells with bland nuclear features (Fig. 45.14).100 The neoplastic epithelial cells may be arranged singly, on edge, in sheets, or as small papillary tufts. The background usually shows mucin with chronic inflammatory cells, histiocytes, and debris. The degree of cellularity varies and tends to increase with higher grades of intraepithelial neoplasia. Stromal components are not usually present. With malignant transformation, features of adenocarcinoma with or without mucin and cellular debris are often evident.101 The definitive diagnosis requires correlation with clinical information, imaging studies, and histopathologic confirmation of ovarian-type stroma surrounding the cyst.94 The cyst fluid may be assayed for carcinoembryonic antigen and CA 19-9 to distinguish neoplastic from non-neoplastic liver cysts (Box 45.8).98,102,103

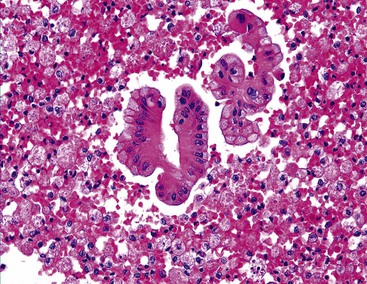

Biliary intraductal papillary neoplasm is a fusiform or cystic (unilocular or multilocular) luminal dilation in communication with the biliary tract. The affected intrahepatic bile ducts are typically filled with a noninvasive papillary or villous biliary neoplasm covering delicate fibrovascular stalks, and mucin may be seen. Aspirates are typically hypercellular, comprising broad and often double-layered sheets of ductal cuboidal or columnar epithelium with a distinctive three-dimensional, complex-branching papillary configuration (Fig. 45.15).104 The sheets of cells do not form a honeycomb pattern but are crowded. Phenotypes include pancreaticobiliary, intestinal, gastric, and oncocytic forms. The epithelium shows intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles and occasional signet ring cells. The nuclei show variable abnormalities. Psammoma bodies may be identified. Intraductal papillary neoplasm with associated invasive carcinoma has the highest degree of cellularity and pleomorphism (Box 45.9).

Metastases

Metastatic papillary carcinomas of the pancreas and ovary can simulate intraductal papillary neoplasms. Smears may contain numerous finger-like fibrovascular stalks lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelium with cytologic atypia.

Cystic Lesions without an Epithelial Lining

Non-neoplastic Cysts

Aspirates of non-neoplastic cysts typically reveal an abundant amount of turbid, brown fluid with inflammatory cells, macrophages, fibrin, debris, and bile or hematoidin pigment. The fluid lacks lining epithelial cells but may contain benign cells from surrounding liver parenchyma. The differential diagnosis includes inflammatory/infectious cysts, cystic hematomas, as well as true cysts and cystic neoplasms. Secondary bacterial infection may produce cyst fluid that contains abundant neutrophils and proteinaceous background debris. However, the presence of a neoplastic lining epithelium or background mucin excludes the diagnosis of a non-neoplastic cyst.

Neoplastic Cysts and Tumor-like Lesions

Cavernous Hemangioma

Cavernous hemangiomas are usually asymptomatic, and they are usually diagnosed incidentally during the workup for other conditions, such as during the process of staging a malignancy, and they can be difficult to distinguish from metastasis radiologically.105–108 Hemorrhagic aspirates are often considered unsatisfactory. The nondiagnostic appearance of blood with loose rather than dense fibrous connective tissue and few or no background hepatocytes raises the possibility of a hemangioma in the proper clinical setting (Fig 45.16). Histologic material is crucial in establishing a specific diagnosis (Box 45.10).

Mesenchymal Hamartoma

Aspirates of mesenchymal hamartomas are obtained mainly in the pediatric population, with rare exceptions, and usually show clusters of epithelial and mesenchymal or spindle-shaped cells with bland-appearing nuclei admixed with loose connective tissue (Fig 45.17).109–112 However, aspiration cytology rarely enables a definitive diagnosis, and because hepatoblastomas or malignant mesenchymal tumors are difficult to exclude confidently, cytology is of limited value (Box 45.11).

Cystic Degeneration in a Benign or Malignant Tumor

Solid tumors may undergo central necrosis and cavitation, simulating cysts radiologically. A necrosis-associated tumor should raise the suspicion of an abscess.84 Necrosis is more likely to occur in malignant lesions, such as squamous cell carcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, and metastases from colorectal adenocarcinomas and nonkeratinizing undifferentiated carcinoma in the nasopharynx. The diagnostic cells may be obscured by the process.

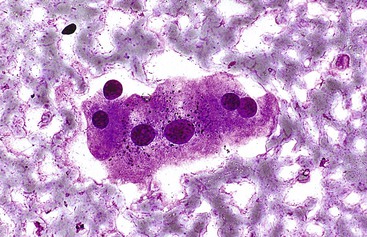

Undifferentiated Embryonal Sarcoma

Although most undifferentiated embryonal sarcomas appear ultrasonographically as solid lesions, CT and MRI imaging may detect a low-attenuation mass with a cystic appearance. Most cystic structures result from liquefactive necrosis and blood clots; however, true cystic spaces may also occur.75 Aspirates recapitulate the histologic pattern of the tumor.113–117 Smears are usually composed of spindle cells and myxoid tissue, intermixed with pleomorphic cells ranging from small round cells to larger multinucleated giant cells. Giant cells have bizarre nuclei and massively deranged chromatin structure. They contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles and are AFP negative, PAS positive, but diastase-resistant hyaline globules (Fig. 45.18); extracellular globules may also be present. Immunostaining for α1-antitrypsin, α1-antichymotrypsin, and carcinoembryonic antigen is positive in tumor cells. The cytologic differential diagnoses include rhabdomyosarcoma, hepatoblastoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, NOS (so-called malignant fibrous histiocytoma), and poorly differentiated HCC (Box 45.12).

Solid Lesions of the Liver

Hepatocellular Appearance

Benign Hepatocellular Nodules

Benign hepatocellular nodules, which can be non-neoplastic or neoplastic, such as focal fatty changes, large regenerative nodules, dysplastic nodules, focal nodular hyperplasia, and hepatocellular adenomas, are discussed together because they share common cytologic features, including fatty changes (Box 45.13).22,118,119 Unfortunately, it is not always possible to distinguish these entities on the basis of smear cytology alone. They all can mimic well-differentiated HCC.

A focal fatty change may simulate a mass lesion radiologically.79,80 Aspirates are composed of a polymorphous population of enlarged, fat-laden, non-neoplastic hepatocytes intermingled with bile duct epithelial clusters. Oil globules may be seen in the background on air-dried smears.

Aspirates from large regenerative nodules are similar to those from cirrhosis, in which a polymorphous liver parenchymal population shows evidence of hyperplasia and hepatocellular-interface restoration (i.e., bile ductular epithelium and stromal fragments).63,72 Hyperplastic hepatocytes occur in two-cell-thick cords and exhibit slight polymorphism and binucleated forms. Normal bile duct epithelial clusters should be differentiated from bile ductular epithelial cells, which appear as curved, narrow, double-stranded rows of cells with overlapping, dark, oval nuclei; scant or absent cytoplasm; and a high N : C ratio. Nuclear disarray may be disconcerting. Ductules can be seen emanating from the jagged edges of sizeable parenchymal fragments (Fig. 45.19). Stroma may be seen in the background. The presence of ductules should raise the diagnostic threshold for a malignant process.

Hepatocellular atypia, such as large cell and small cell changes (e.g., dysplasia), are considered neoplastic precursor lesions and may be detected in aspirates from cirrhotic livers.75,78,119–125 Hepatocytes with large cell changes show corresponding cellular and nuclear enlargement and mild nuclear atypia; but the normal N : C ratio (i.e., one to three or less) is maintained (Fig. 45.20). Hepatocytes with small cell changes are small and monotonous, with a subtle increase in the N : C ratio. The nuclear size is similar to that of normal hepatocytes, but there is less cytoplasm, imparting an impression of nuclear crowding (Fig. 45.21).126

Aspirates of low-grade dysplastic nodules show hepatocytes that exhibit large cell changes, whereas those from high-grade dysplastic nodules show hepatocytes with small cell changes. Dysplastic hepatocytes tend to occur singly or in narrow cords, usually one to two cells thick. Transgressing endothelium is not a feature. It is almost impossible to distinguish a small cell change from a well-differentiated or early HCC.126,127 The key to recognizing a large cell change as benign is the sporadic placement of these cells in a background of otherwise reactive-appearing hepatocytes and accompanied by bile ductal or ductular epithelium and stroma. Availability of histologic material for immunohistochemistry is invaluable.

Patients with cirrhosis without iron overload can accumulate iron within regenerative or dysplastic nodules, which are called siderotic nodules. Siderotic dysplastic nodules are considered to be premalignant, whereas siderotic regenerative nodules are a marker for severe viral or alcoholic cirrhosis.73,74 Iron-free foci in patients with genetic hemochromatosis are likely to be malignant.77,78

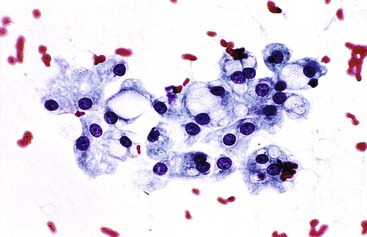

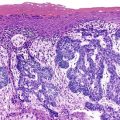

Focal nodular hyperplasia is characterized by a proliferation of hepatocytes surrounding a central scar containing blood vessels and bile ducts. A brisk ductular reaction is often seen at the hepatocellular-stromal interface.128 Aspirates typically contain a polymorphous population of cells, but this varies.129 Hyperplastic hepatocytes abound in one- to two-cell-thick cords. Bile duct epithelium is usually evident (Fig. 45.22). The presence of ductular epithelium supports the benign nature of this lesion, but this feature can be mistaken for adenocarcinoma if it is the dominant component of the aspirate. A possible diagnostic pitfall is mistaking reactive stroma for a spindle cell neoplasm.130 A characteristic geographic immunostaining pattern is seen with the use of glutamine synthetase.131 Without radiologic demonstration of a central scar, it may not be possible to differentiate focal nodular hyperplasia from large regenerative nodules on smear cytology, because both show features of regeneration.

Aspirates of a hepatocellular adenoma are hypercellular and typically contain well-differentiated hepatocytes occurring in one- to two-cell-thick cords (Fig. 45.23). There is no significant atypia. Transgressing endothelium is common, but peripheral endothelium is lacking. The tumor cells are polygonal and have moderate granular cytoplasm. Some cells display fatty or clear cell changes and bile or lipofuscin pigment. Bile duct epithelium is absent. The reticulin framework is usually well preserved. CD34, which highlights capillarization of the sinusoids in HCC, can also positively stain adenomas, particularly in the periseptal areas. This may be a diagnostic pitfall in assessing small, fragmented liver core specimens and cell block preparations. Glypican 3 staining should be focal and weak at best.132–134 The diagnosis requires clinical correlation. Chapter 55 provides more information on immunohistochemical markers of adenomas in tissue sections.135

A nodule-in-nodule lesion occurs when an HCC subnodule develops within a parent dysplastic or regenerative nodule.136 Representative FNAB samples may be a problem because of the focality of proliferative clones within these nodules. Classic aspirates reveal more than one population of lesional hepatocytes, including malignant hepatocytes and dysplastic or hyperplastic hepatocytes in the background (Fig. 45.24). The presence of biliary epithelial cells varies.

Primary Malignant Hepatocellular Neoplasms

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

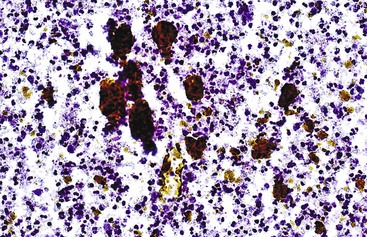

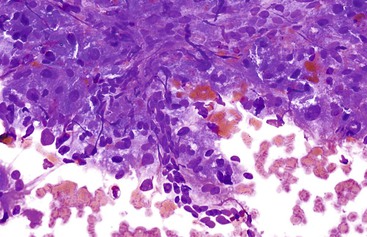

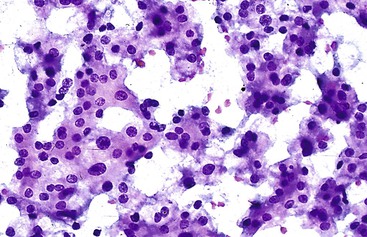

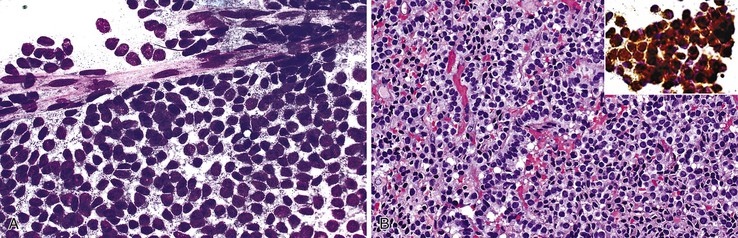

HCCs exhibit marked heterogeneity in differentiation, histologic patterns (i.e., trabecular-sinusoidal, pseudoacinar, and solid types), and cell morphology. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of HCC lists the classic type, several variants, and special types.75 Sampling limitations of the FNAB technique and cytohistologic challenges in the face of this diversity are recognized. Most tumors show relatively good hepatic preservation and obvious malignant features. However, diagnostic dilemmas exist at both ends of the spectrum—cytologic features of malignancy are lacking at the well-differentiated end and resemblance to hepatocytes is lacking at the poorly differentiated end.137 The cytomorphologic features of HCC are summarized in Box 45.14.61,63,138–145 The cytologic nuclear grading of HCC into well-, moderately, and poorly differentiated is outlined in Boxes 45.15 through 45.17.72

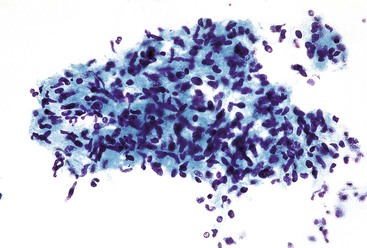

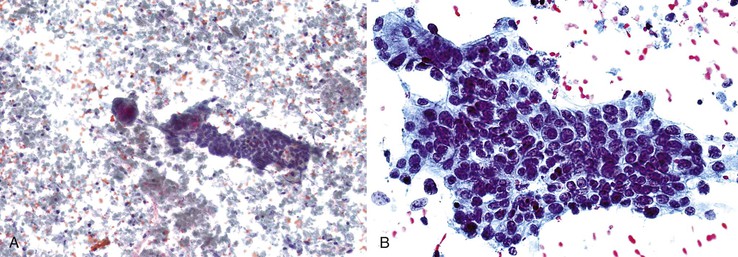

Cellularity

Aspirates are typically hypercellular. Low-power scanning usually shows a granular smear pattern composed of trails of irregular tumor clusters, which reflects the prominent trabecular-sinusoidal pattern (Fig. 45.25).

Epithelial Cohesiveness

Cohesion is the rule for HCC. However, a strong tendency to dissociation is observed in very-well-differentiated and very-poorly differentiated tumors. Dispersed, small clusters or single cells are seen in smears of very-well-differentiated HCC with cords that are one or two cells thick and in poorly differentiated HCC with deficient reticulin.

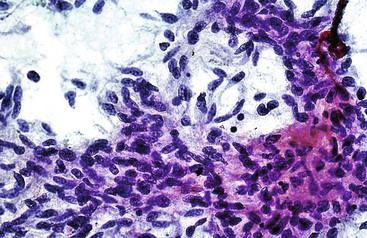

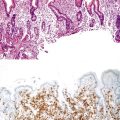

Vascular Patterns

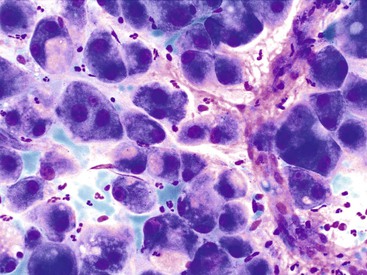

Arborizing tongues and nests of cohesive tumor cells more than two cells thick are wrapped peripherally by endothelium (Fig. 45.26).138,142,146 Although the trabecular-sinusoidal pattern is cytologically identified in less than one half of tumors, it is specific for HCC and is one of the most important diagnostic clues for separating reactive and benign neoplastic proliferations from well-differentiated HCC.51,138,142,147 More often, the pathologist encounters loosely cohesive sheets of tumor cells with transgressing, arborizing, or central endothelial proliferations (Fig. 45.27). Basement membranes are best appreciated in Giemsa-stained preparations as pink tramlines.61 Although this vascular appearance is not specific for HCC, it is rarely seen in non-neoplastic hepatocellular nodules, cirrhosis, and hepatitis.142

A pseudoacinar pattern is common. The cystically dilated canalicular spaces contain bile or pale secretions and are surrounded by polygonal cells with central nuclei similar to the adjacent sibling cells. The subtle rosette-like pattern is best appreciated by examining several planes in the tissue (Fig. 45.28). In some cases, the surrounding cells may assume a more columnar shape with basal nuclei simulating true acini. The concomitant presence of malignant acini may imply a combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (CHCC-CC).

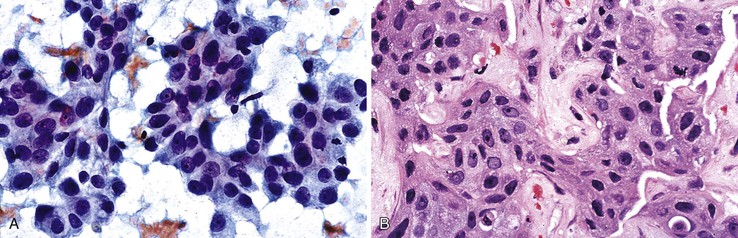

Cellular Characteristics

A monomorphous population of atypical hepatocytes usually prevails. Tumor cells may be smaller, larger, or the same size as non-neoplastic hepatocytes. Better-differentiated HCCs are characterized by polygonal cells with well-defined cell borders; ample, dense granular cytoplasm; a uniformly elevated N : C ratio; a central, round nucleus; well-delineated nuclear membranes; macroeosinophilic nucleoli; and fine, irregularly granular chromatin (Fig. 45.29).51,142 Mitoses increase in number with nuclear grade. Well-differentiated HCC cells tend to be conspicuous by their small size, striking monotony, subtle increase in the N : C ratio, and nuclear crowding (Fig. 45.30). Poorly differentiated HCC cells tend to be highly pleomorphic with overlapping nuclei, thin nuclear membranes, irregular nuclear contours with convoluted forms, hyperchromasia, and numerous mitoses (Fig. 45.31).

Atypical naked hepatocytic nuclei may be plentiful in all grades of HCC (Fig. 45.32). This finding is a more reliable feature for separating primary from metastatic tumors than it is for differentiating benign from malignant tumors.140

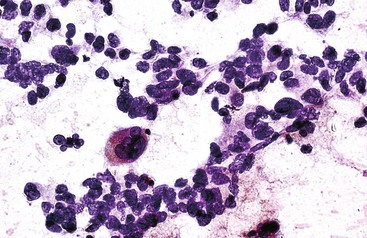

Multinucleated tumor giant cells may be osteoclastic or pleomorphic (Fig. 45.33). The former type shows nuclear features that are similar to those of sibling cells. Although rare, tumor giant cells may be present even in lower grades of HCC. Their presence does not necessarily indicate a higher-grade tumor.

Pigments

Although observed in less than one half of all cases, bile production by malignant cells is pathognomonic of HCC with rare exception, and no further studies are necessary.138 Bile within canaliculi and pseudoacini appears as greenish-black, ropey strands and blobs, respectively, on Giemsa-stained smears. The presence of bile, however, is not a helpful finding in differentiating benign from malignant neoplasms. The pathologist should be on the alert for nonhepatocellular tumors that cause obstruction with resultant cholestasis. A concomitant absence of lipofuscin pigment or iron-free hepatocytes in patients with iron overload supports a malignant diagnosis.

Cellular Inclusions

Intracytoplasmic fat and glycogen vacuoles are common in HCC (see Variants of Hepatocellular Carcinoma). Intracytoplasmic inclusions include hyaline globules, pale bodies, and Mallory bodies. Hyaline globules, such as α1-antitrypsin and AFP, are not specific for HCC or malignancy in general (see Fig. 45.32). Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions are also not specific (Fig. 45.34). The presence of mucin supports an adenocarcinoma.

Background Elements

Bile duct epithelial cells, if present, should be few and far apart. The background may be hemorrhagic, necrotic, or both.

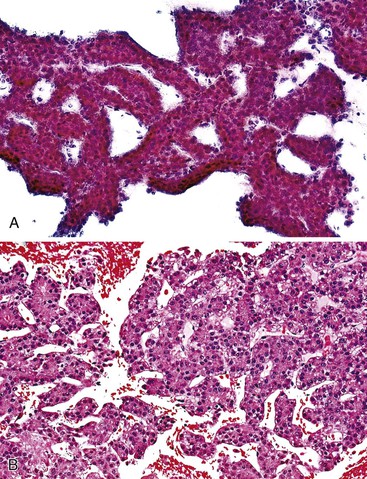

Cell Blocks and Microbiopsies

Cell blocks and microbiopsies may provide additional architectural and morphologic clues to the diagnosis. It is not uncommon for hepatocytic features to be more apparent in the histologic sections than on smear cytology, potentially precluding the need for further confirmatory studies. Cords that are three or more cells thick are one of the most pathognomonic features of well-differentiated HCC. The use of Gomori silver stain for reticulin fibers on smears or cell blocks can prove diagnostically helpful.51,147–149 Presence of an abnormal pattern of reticulin supports a diagnosis of HCC (Fig. 45.35). Perls (Prussian blue) iron stain is positive in hemosiderin-laden hepatocytes in hemochromatosis, but malignant hepatocytes typically remain unstained.77,78

Variants of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Adequate representative sampling of hepatocellular carcinoma, a notoriously heterogeneous malignancy, will become even more crucial in the future, when molecular subclassification of HCC is implemented for the purpose of personalized, molecularly targeted therapy.23

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Fatty Changes

Fatty changes may occur in all sizes and grades of HCC, independent of the steatosis present in non-neoplastic liver tissues (Fig. 45.36). The differential diagnosis includes well-differentiated hepatocellular nodules with fatty metamorphosis.150 Poorly differentiated HCC cells may simulate malignant lipoblasts or signet ring cells.

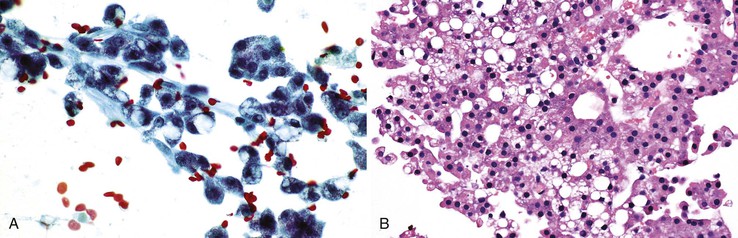

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Clear Cell Changes

Malignant hepatocytes may display clear, vacuolated, glycogen-laden cytoplasm that is best appreciated with Giemsa staining (Fig. 45.37).151–153 Differential diagnoses include metastatic renal cell carcinoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, and angiomyolipoma.154,155

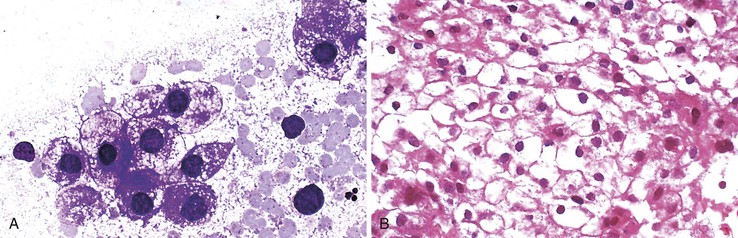

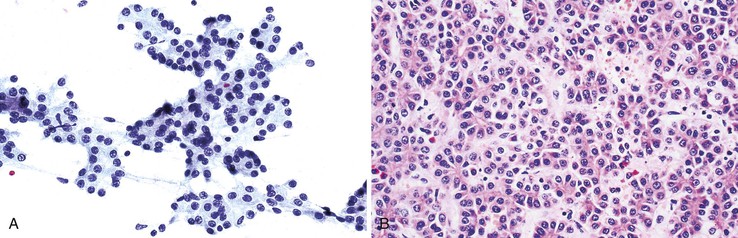

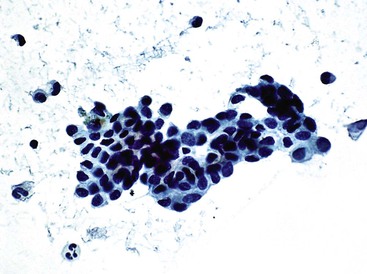

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Small Cell Changes

Loosely cohesive small tumor cells may show scant cytoplasm, round nuclei, a high N : C ratio, granular chromatin, and a small nucleolus (Fig. 45.38). They mimic neuroendocrine tumors and have a similar tendency to dispersion and microacinar formation.147,156–159 However, the salt and pepper chromatin pattern of endocrine tumor cells is typically lacking. Closer scrutiny of the smears may reveal more classic-looking HCC in other areas.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Pleomorphic Features

HCC cells with pleomorphic features are poorly differentiated and have a dyshesive tendency (Fig. 45.39). Multinucleated tumor giant cells and necrosis may be present.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Spindle Cell Features

Pleomorphic, spindle-shaped cells are indistinguishable cytologically from sarcoma cells (see Sarcomatoid Hepatocellular Carcinoma).160

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Giant Cell Features

A pure giant cell variant is rare, and it should be differentiated from other giant cell carcinomas and sarcomas. The pathologist often encounters bizarre multinucleated giant cells with abnormal mitoses in the company of spindle cells (Fig. 45.40).

Special Types of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Fibrolamellar Variant of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The fibrolamellar variant of HCC is particularly prone to producing a dispersed smear pattern. The polygonal tumor cells are large (approximately three times larger than normal hepatocytes), as are the nucleus and nucleolus. The N : C ratio is deceptively low (less than one to three). There is abundant, dense oxyphilic cytoplasm with numerous intranuclear inclusions, intracytoplasmic hyaline globules, and pale bodies (Fig. 45.41).161,162 Peripheral and transgressing endothelium is usually lacking. The dense lamellar fibrosis is more likely to be seen in histologic material (Box 45.18).

Scirrhous Type of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The scirrhous type of HCC is rare. It should not be confused with the fibrolamellar variant of HCC and CC.

Undifferentiated Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Undifferentiated HCC cells may be loosely cohesive or show a tendency to dissociate. They are pleomorphic and nondescript, often without cytohistologic or immunohistochemical clues to their histogenesis.75

Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma

The small, pleomorphic cells of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma are admixed with prominent lymphocytes. Tumor cells may test positive for Epstein-Barr virus.75

Sarcomatoid Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The purely sarcomatoid variant of HCC is rare. It is more often seen in conjunction with tumor giant cells (Fig. 45.42). Extensive sampling may reveal areas of conventional HCC.160 This variant should be differentiated from true sarcomas.

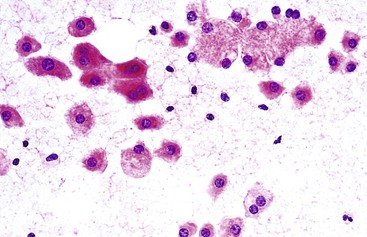

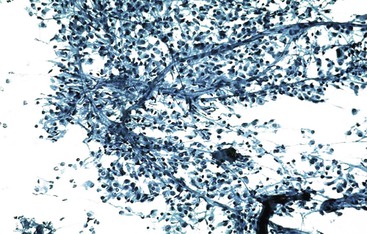

Very-Well-Differentiated Hepatocellular Carcinoma

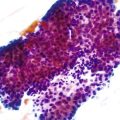

Very-well-differentiated HCC is a tumor that looks hepatocytic but does not appear obviously malignant. Aspirates from small, early HCCs are nearly impossible to differentiate from high-grade dysplastic nodules because they are both composed of hepatocytes with small cell changes. The smear pattern may not be useful because there is a tendency to dispersion of the cells.

Cytologic features indicating HCC include small cell size, an increased N : C ratio, cellular monomorphism, nuclear crowding, cords that are more than two cells thick, atypical naked nuclei, and lack of bile ducts.51,63,134,163,164 Cytologic parameters that distinguish very-well-differentiated HCC from cirrhosis include well-defined cell borders, scant cytoplasm, monotonous cytoplasm, thick cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and an increased N : C ratio (Fig. 45.43).165 Vascular patterns may be subtle on direct smears, and the hepatocytic phenotype may be attenuated in liquid-based cytology (Fig. 45.44). Availability of cell blocks or microbiopsy material is helpful for assessing the architectural details and for ancillary stains.166

Diagnostic accuracy remains a challenge. Indeterminate reports are often rendered and include statements such as, “Features are those of a well-differentiated hepatocellular nodule. A well-differentiated HCC cannot be excluded.”

Immunohistochemistry

An armamentarium of antibodies is available for comparative immunohistochemical analysis of primary and metastatic tumors of the liver.167–169 A panel of immunostains has more discriminant value than individual stains. Immunohistochemistry is performed on cell blocks and microbiopsies rather than on smears, cytospins, and liquid-based preparations. Careful light microscopic assessment of the histologic sections is crucial, and judicious use of immunostains is imperative when material is limited.1 Double-staining protocols may help optimize tissue use.170,171 Immunohistochemical results should always be interpreted within the broader clinical context of the case.

Stepwise logistic regression analysis has shown that an immunostain panel consisting of glypican 3,167 hepatocyte paraffin 1 (Hep Par 1),172–177 MOC-31 monoclonal antibody,178–180 and cytokeratins CK20 and CK7/CK19180–182 is most useful in diagnosing and differentiating HCC from metastatic adenocarcinoma on FNAB material, with accuracy rates of 90.5% and 91.7%, respectively.179 In the HCC group, glypican 3 is the most sensitive (81%), followed by Hep Par 1 (71.4%) and polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (pCEA) (50%). In the metastatic adenocarcinoma group, MOC-31 is most sensitive (79.2%), followed by CK7 (41.7%).180,183

For hepatocellular nodules, the objectives of immunohistochemistry are twofold: to prove hepatocellular histogenesis and to demonstrate the malignant status of hepatocytes.184 For investigation of hepatocellular histogenesis, the panel should include Hep Par 1,172,173,176 thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1),185 and pCEA or CD10 to demonstrate canalicular formation.175,180,183,186–189 Arginase-1 has recently joined the ranks of Hep Par 1.189a However, Hep Par 1 and arginase-1 do not distinguish benign from malignant hepatocytes.184 For determining malignancy, the panel should include glypican 3,190–195 glutamine synthetase 196 and heat shock protein 70.197 Positivity for two of three of these biomarkers indicates HCC.198 Strong glypican 3 staining distinguishes benign from malignant hepatocytic proliferations, but a negative stain result does not exclude a malignant diagnosis because of the heterogeneity in staining patterns.199 Glutamine synthetase shows a geographic staining pattern in focal nodular hyperplasia.131

Glypican 3, a heparin sulfate proteoglycan anchored to the plasma membrane, is an oncofetal protein that is over-expressed in HCC at the mRNA and protein levels. This marker may be detected in the serum and tissue of patients with HCC but not in benign hepatic lesions, and it has a higher specificity than AFP.190,200 Immunohistochemistry studies have indicated great promise for glypican 3 in the distinction between benign and malignant hepatocytes on histologic sections and on cytology material.192,201

A positive AFP result is helpful, but a negative result does not rule out malignancy.75 Serum levels of AFP greater than 500 µg/L are highly associated with HCC, but not all tumors, particularly the fibrolamellar variant, are associated with elevated levels. Staining for AFP may occasionally be positive in reactive processes. Demonstration of AFP positivity points to a malignant tumor of hepatocellular origin, provided nonseminomatous germ cell tumors and extrahepatic AFP-producing carcinomas have been excluded. Unfortunately, this tumor marker has such low sensitivity (40%) that it is no longer recommended as part of the panel.174,187

Immunostaining for CD34 is negative in normal hepatic sinusoids. This endothelial cell marker highlights diffuse sinusoidal capillarization in HCC.132,202 However, the CD34 result should be evaluated with caution when differentiating benign from malignant hepatocellular nodules, because diffuse sinusoidal capillarization may be encountered in hepatocellular adenomas and focal nodular hyperplasia.203 It demarcates cord thickness and is very helpful in cases of poorly differentiated HCC in which there is virtually no reticulin.51,148,149

In addition to highlighting lesions of a pure biliary immunophenotype, CK7/CK19 is also part of a panel of immunostains often used to elucidate a possible hepatic progenitor cell origin of certain primary liver carcinomas. The immunostain can also be used to demonstrate an absence of a ductular reaction at the invasive border of a small HCC, separating it from a high-grade dysplastic nodule.204 The prognostic significance of CK7/19 expression in HCC is still being evaluated.182

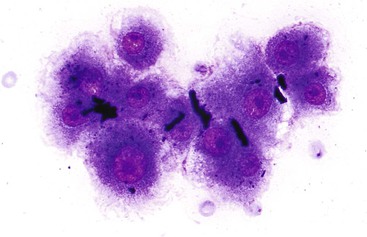

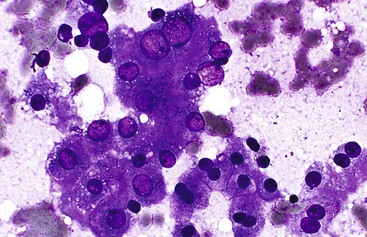

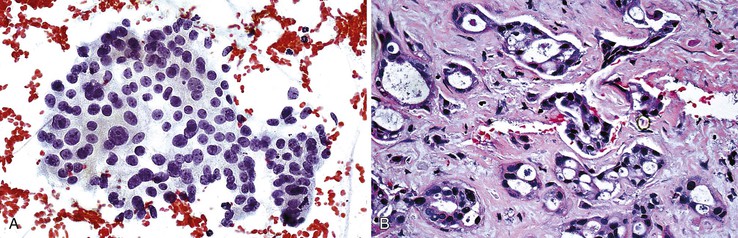

Hepatoblastoma

Aspirates of hepatoblastoma can have a heterogeneous appearance, depending on the cell types in the tumor.205,206 Smears of the epithelial or mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumor type are dominated by epithelial cells, which may be fetal, embryonal, or anaplastic (Fig. 45.45). Fetal cells resemble normal hepatocytes, but they are usually smaller. The nuclei are central, round, and bland, and the cytoplasm may contain fat and glycogen.207,208 The embryonal cell type is more primitive and undifferentiated, showing hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm. These cells may form rosettes and trabeculae.207,209 The anaplastic cell type resembles other small, round, blue cell tumors of childhood and is impossible to distinguish from neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor on morphology alone.210,211 The mesenchymal component, if present, is a cellular spindle cell proliferation, but heterologous elements may also be evident, including osteoid, cartilage, skeletal muscle, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.207–209 A myxoid matrix has been described.212

The primary differential diagnosis includes fetal-type hepatoblastoma, HCC, and embryonal or anaplastic hepatoblastoma, as well as other pediatric small, round, blue cell tumors.209,210 Cytomorphologic features alone cannot help to narrow the differential diagnosis; it requires ancillary studies and clinicopathologic correlation. Hep Par 1 positivity supports a hepatic primary over other small, round, blue cell tumors of nonhepatic origin,213 but this stain cannot help to separate hepatoblastoma from HCC. Cytokeratin (CK) staining can be helpful because most hepatoblastoma cells stain positively with high-molecular-weight CKs,214 whereas most HCCs do not. Both tumors stain with low-molecular-weight CKs (e.g., Cam 5.2).214 Polyclonal CEA stains hepatoblastomas with a variable and inconsistent canalicular or cytoplasmic pattern, depending on the type of hepatoblastoma.213 This stain cannot help to distinguish hepatoblastoma from HCC, but it can help to differentiate primary from metastatic tumors (Box 45.19).

Combined Hepatocellular-Glandular Appearance

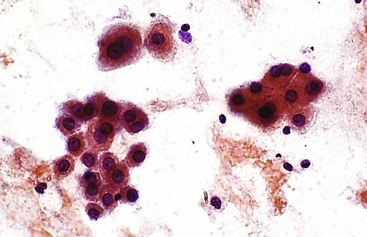

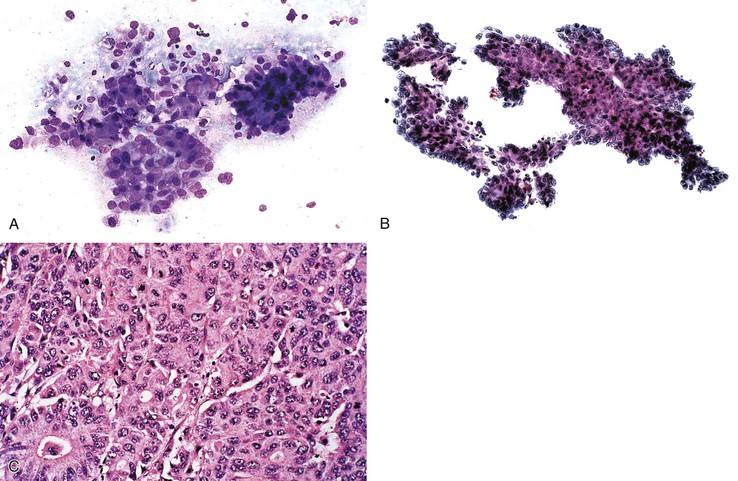

Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma

Combined HCC-CC is a rare entity.75 The classic type is characterized by an intimate admixture of HCC, adenocarcinoma, and “transitional epithelium” (Fig. 45.46).215–218 The HCC component may be obscured by other, more plentiful elements. The adenocarcinoma component may be highly variable in appearance. The transitional cells, which often predominate, often display hybrid features that are difficult to categorize. They may resemble malignant hepatocytes with a trabecular arrangement, but they may also exhibit acini with nuclear palisading. In contrast, they may display irregular nuclear contours, indistinct nucleoli, and less granular cytoplasm.

Differentiating pseudoacini from true acini may be difficult. Mucin may not be present. Sampling issues may cause one cell population to predominate. The various cellular components may not always exhibit their expected immunophenotypes. Combined HCC-CC may show stem cell features of the three subtypes: typical, intermediate cell, and cholangiolocellular.75,219–222 Immunohistochemical confirmation of the presence of hepatic stem cells is difficult on limited tissue samples.182

Nonhepatocellular Appearance

Benign Nonhepatocellular Lesions

Bile Duct Hamartoma, Bile Duct Adenoma (Peribiliary Gland Hamartoma)

Bile duct hamartomas, also called von Meyenburg complexes, are small incidental subcapsular developmental anomalies. Bile duct adenoma is considered a nodular proliferative response to injury of peribiliary glands surrounding major bile ducts. Both may manifest as mass lesions mimicking neoplasms.223 Aspirates show glandular pattern (Fig. 45.47). Cell blocks may be helpful (Box 45.20).

Angiomyolipoma

Hepatic angiomyolipom is regarded as a tumor of perivascular epithelioid cells (PEComa) that exhibits dual myomatous and lipomatous differentiation and melanogenesis.224 Its protean morphologic appearances result from a combination of adipose tissue, smooth muscle (spindled or epithelioid) tissue, and thick-walled blood vessels. Hepatic lesions are less classic than the renal counterpart, in which the lipomatous nature of the tumor is usually grossly apparent.225–229 The epithelioid myoid elements may appear as oncocytic, clear cell, or pleomorphic, which can mimic HCC, renal cell carcinoma, sarcoma, and melanoma (Fig. 45.48).230 Large, epithelioid, clear, myoid cells with a spider cell appearance (caused by perinuclear condensation of the cytoplasm and bizarre nuclei) may appear to be malignant. However, the absence of nuclear hyperchromasia and mitoses in the face of such an aggressive-looking lesion lends to its benignity.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis is common. Positive staining with the monoclonal antibody HMB-45 and other melanogenosis markers such as melan-A (i.e., MART1) helps to confirm the diagnosis.231 S100 protein, CD117, actin, desmin, and vimentin expression varies. Diagnostic difficulty arises when the fatty component is scant or focal or is not sampled, which may suggest a spindle cell lesion of the liver. In some cases, this tumor may be mistaken for liposarcoma because of the presence of lipoblast-like cells (Box 45.21).

Primary Malignant Nonhepatocellular Lesions

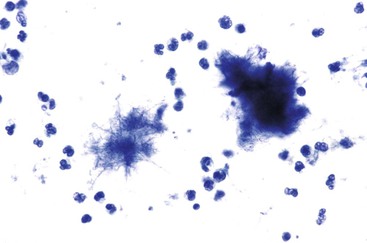

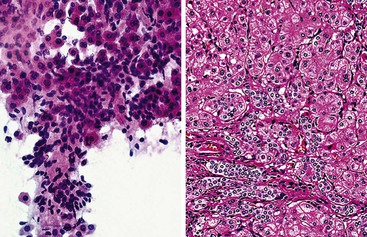

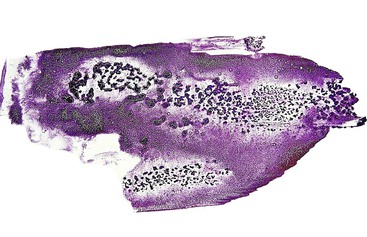

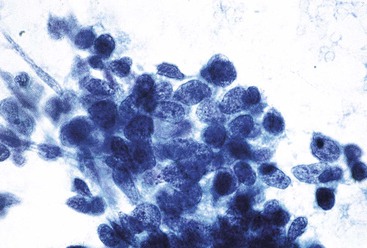

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

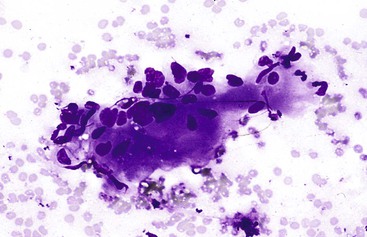

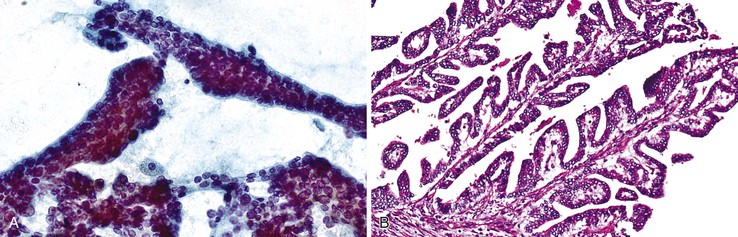

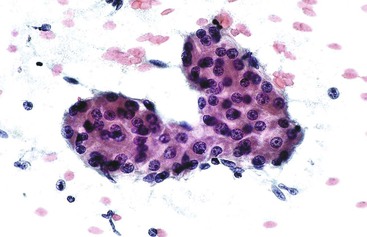

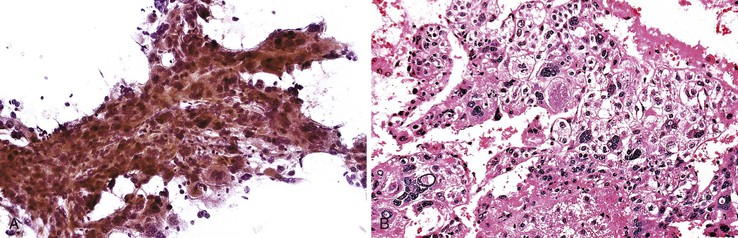

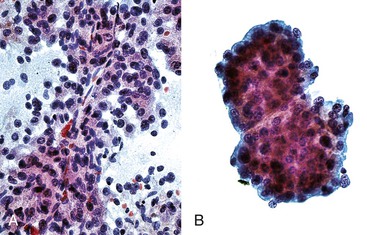

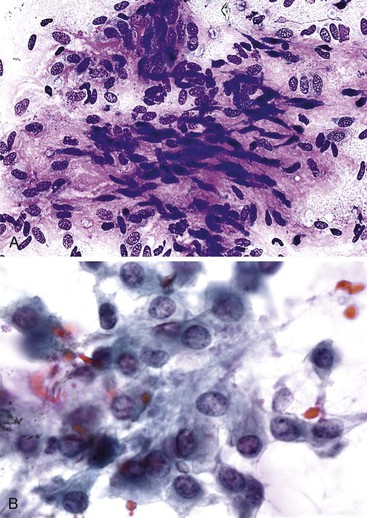

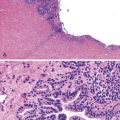

The most common histologic appearance of mass-forming, intrahepatic CCs is a well- to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma forming tubules and infiltrating sclerotic stroma.75,232 However, phenotypic diversity does exist.233 EUS-FNA may be used to procure tumor tissue.234,235 The degree of cellularity and desmoplasia determines whether aspirates are scanty or produce a readily recognizable adenocarcinoma with nonspecific features.72 A low-power smear pattern demonstrating irregular, variously sized sheets of atypical to malignant glandular cells with peripheral palisading nuclei and branching, tapered columns is highly reminiscent of bile duct epithelium and suggests a primary adenocarcinoma (Fig. 45.49).

Well-differentiated CC resembles normal bile duct epithelium. Sheets of cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells have a honeycomb appearance, with round to eccentric nuclei, fine chromatin, small to inconspicuous nucleoli, and ample, lacy, or vacuolated cytoplasm. Abrupt cell and nuclear enlargement with irregular nuclear membranes and prominent nucleoli within the same group are an indication of malignancy. Disorderly growth with crowding, piling up, and loss of nuclear polarity impart a “drunken” honeycomb appearance.

Less differentiated tumors exhibit greater degrees of pleomorphism and mitotic activity. Microacinar formation, intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles in signet ring cells, and extracellular mucin may be evident. Papillary structures and squamous features are sometimes seen. In highly desmoplastic CCs, a few obscure, dissociated tumor cells may be entrapped in stromal fragments. A useful clue is the presence of biliary intraepithelial neoplasia in the residual sheets of biliary epithelium.

Liver flukes (Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini) are predictive of CC.75 The background may contain prominent ductular clusters.236 Tumor diathesis is not a feature.

The differential diagnosis includes metastatic adenocarcinomas and poorly differentiated HCCs. The tumor cells may also be part of combined HCC-CC.150,215–218 The rare small cell type of CC should be differentiated from other small, round cell malignancies. Ductular cells are much smaller than CC cells,236 and they should not be mistaken for CC.221 CCs may be associated with a cystic component when there is cystic degeneration, cystic obstructive dilation of intrahepatic bile ducts, or malignant transformation in preexisting fibropolycystic disease.75

Histologic material may reveal the characteristic pattern described previously. A fortuitous finding is biliary intraepithelial neoplasia in a residual bile duct.237 These specimens also provide accessible tissue for CK7/CK19 immunostaining (Box 45.22).

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Aspirates from this low-grade malignant vascular tumor are characterized by a dyshesive population of atypical cells in a clean background, fragments of metachromatic stroma, scattered benign hepatocytes, and bile duct epithelium.238–242 The atypical cells are polygonal with abundant, dense cytoplasm and occasional trailing. Some cells may exhibit a sharp, punched-out intracytoplasmic lumen. The nuclei are round to reniform and contain fine chromatin and occasionally prominent nucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions and binucleated and multinucleated cells can also be seen. Diagnostic pitfalls include confusion with adenocarcinoma and angiosarcoma (Box 45.23).

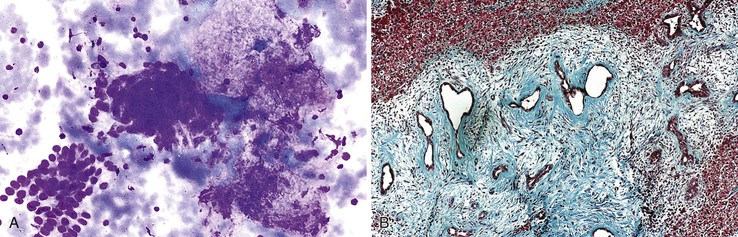

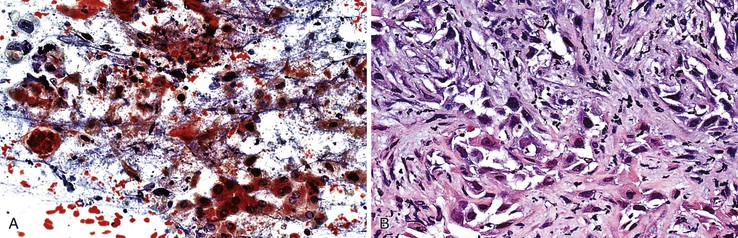

Angiosarcoma

Aspirates of angiosarcoma are bloody and often paucicellular.243 Malignant endothelial cells can be seen interdigitating among reactive hepatocytes. They are easier to appreciate in small clusters than in large clusters, in which they tend to blend with hepatocytes. The tumor cells have elongated, spindle-shaped, hyperchromatic nuclei with a distinct, prominent eosinophilic nucleus and ample cytoplasm. Frequently, huge intracytoplasmic vacuoles, similar to those of signet ring cells, are identified (Fig. 45.50). Sometimes, the tumor cells have a more epithelioid appearance. The differential diagnosis includes spindle cell sarcomas and poorly differentiated carcinomas. Immunostains for endothelial markers such as factor VIII, CD31, and CD34 are frequently but not invariably positive (Box 45.24).244,245

Metastatic Malignant Nonhepatocellular Lesions

Most liver tumors are metastases.75,246,247 Metastatic tumors tend to recapitulate the appearance of the primary tumor. Some nonhepatocellular malignancies may be de novo lesions in the liver. Distinction between a primary and metastatic malignancy has therapeutic and prognostic significance.

Metastatic tumors commonly encountered in FNAB of the liver include those from the colorectum (i.e., adenocarcinoma), pancreas (i.e., adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors), stomach (i.e., adenocarcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumors), breast, lung (i.e., adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and less commonly, squamous cell carcinoma), skin (i.e., melanoma), and bladder (i.e., transitional cell carcinoma). Lymphoma may be identified. Less common but diagnostically more challenging are metastases from the kidney and adrenal gland because of the morphologic overlap with HCC. Sarcomas are rare; the most common type is metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma.

A practical approach to the interpretation of these aspirates is to categorize the cytohistologic findings according to the cytologic patterns listed in Box 45.7.72 The cytologic features helpful in the diagnosis of a variety of metastatic tumors are reviewed along with accompanying supportive ancillary tests and illustrations (Boxes 45.25 through 45.28; Figs. 45.51 through 45.61).

Adenocarcinomas present the most difficulty in establishing a specific site of origin. Primary liver carcinomas that need to be excluded include CC, combined HCC-CC, and cystic mucinous neoplasms with associated invasive carcinoma. The presence of an adenocarcinoma with dirty necrosis likely indicates a colonic primary (see Boxes 45.25 and 45.26; see Fig. 45.51). Ductal carcinoma of the breast tends to be more monomorphous and lower grade (see Box 45.27; see Fig. 45.52). Adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinomas may metastasize to the liver from the pancreaticobiliary tract. Necrosis and a heavy neutrophilic component may obscure tumor cells in some squamous cell carcinomas clinically masquerading as abscesses (Box 45.28; see Fig. 45.53).

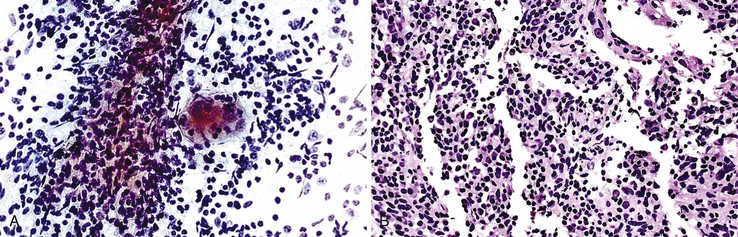

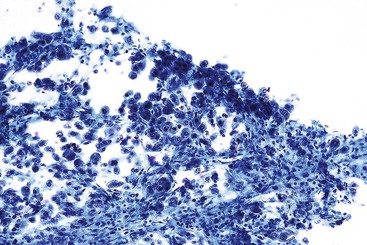

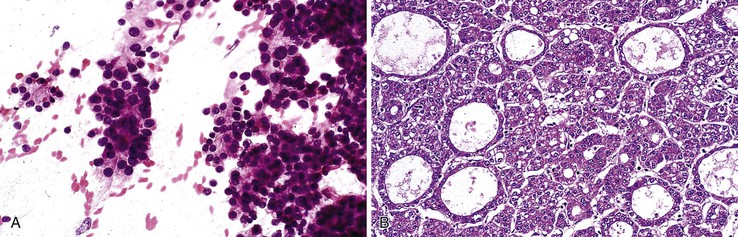

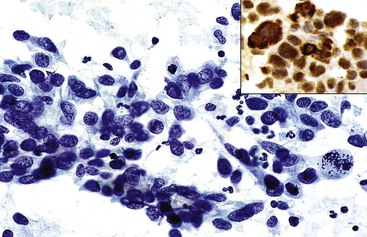

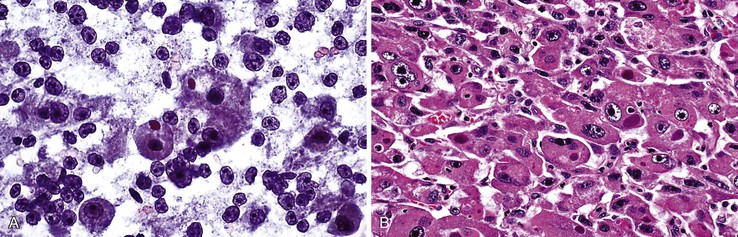

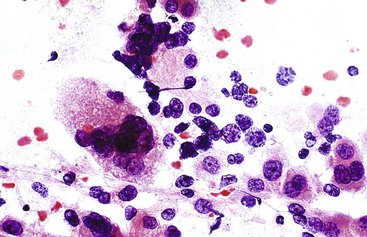

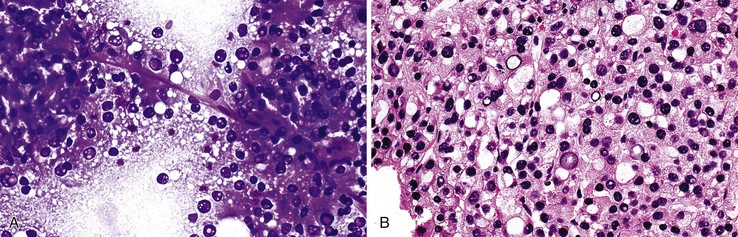

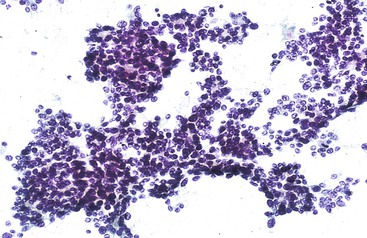

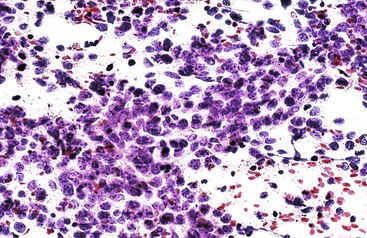

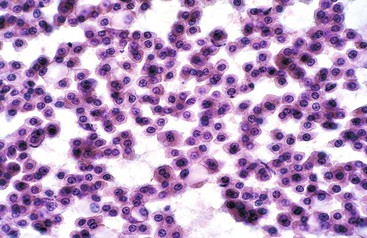

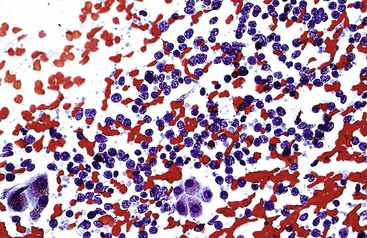

Small, round cell tumors include lymphoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and small cell carcinoma.248,249 If lymphoma is suspected on rapid interpretation, the physician should request a dedicated aspirate for flow cytometry analysis, such as one that is not expressed onto a slide but is suspended in buffered normal saline, Cytolyt solution (Cytyc/Hologic, Marlborough, MA), or RPMI solution (Mediatech, Herndon, VA).250–252 The combination of cytologic evaluation and flow cytometry immunophenotyping is often sufficient to help subclassify non-Hodgkin lymphomas (Box 45.29; see Fig. 45.54). Inflammatory pseudotumors, particularly the lymphoplasmacytic type, should not be mistaken for lymphoma. Neuroendocrine tumors typically show a salt and pepper pattern of chromatin with immunopositivity for chromogranin and synaptophysin (Box 45.30; see Fig. 45.55).253 Nuclear molding and streaking may be discernible in small cell carcinomas (Box 45.31; see Fig. 45.56). Metastatic melanomas often mimic other tumors and are potential diagnostic pitfalls, particularly when the primary site is inconspicuous or the tumor cells are amelanotic (Box 45.32; see Fig. 45.57).

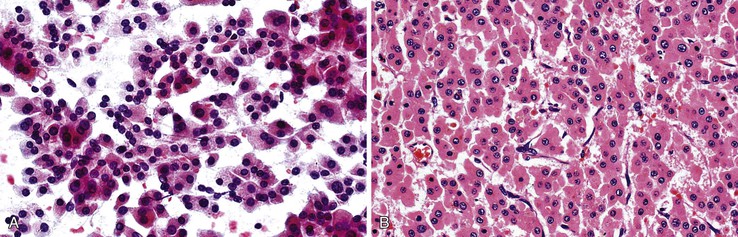

Renal cell and adrenocortical carcinomas are characterized by polygonal cells with clear or oncocytic cytoplasm. Naked round nuclei with distinct nucleoli may be found in the latter. Transgressing endothelium is common in renal cell carcinomas, whereas peripheral endothelium is encountered in adrenocortical carcinomas. The presence of more prominent, complex central and branching vascular tufts should alert the pathologist to the possibility of a nonhepatocellular lesion. Immunohistochemical studies are often helpful (Boxes 45.33 and 45.34; see Figs. 45.58 and 45.59).254,255

Hepatoid yolk sac tumors, similar to HCC and adrenocortical carcinomas, may demonstrate peripheral endothelium, although it is normally seen only on cell block preparations. Tumor cells can be stained for placental alkaline phosphatase, and the result is negative for primary hepatic tumors.256

Spindle cell tumors in the liver are relatively uncommon.257 Metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and leiomyosarcomas are the most important malignancies to recognize for therapeutic purposes. Epithelioid variants of GIST may be confused with hepatocellular and neuroendocrine tumors (Boxes 45.35 and 45.36; see Figs. 45.60 and 45.61).258–263

Not all AFP-producing carcinomas, hepatoid or nonhepatoid in appearance, arise in the liver. Rarely, the tumor can arise in an extrahepatic site such as an adenocarcinoma of the stomach.264,265 These lesions are aggressive, have a proclivity for vascular invasion, and readily metastasize to the liver.