CHAPTER 6 Diagnostic Classification Systems

Diagnostic classification systems (DCSs) for children’s developmental and behavioral problems are important in clinical care, teaching, consultation, and research in the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics. In order to conduct diagnosis and treatment planning, teaching, and research, clinicians with an interest in developmental and behavioral problems need to understand DCSs that are appropriate for children and adolescents. As specialists, developmental-behavioral pediatricians are called on to conduct comprehensive diagnosis and treatment planning for children and adolescents who present with a wide range of behavioral and developmental problems.1 Reimbursement for clinical practice is also tied to specific codes that are used for purposes of diagnostic classification.2 Clinicians with expertise in developmental and behavioral problems are also called on to teach pediatricians and members of other professional disciplines to diagnose and manage these problems.3 Finally, research on the diagnosis and treatment of children with developmental and behavioral problems requires knowledge of the reliability and validity of DCSs.

CHALLENGES OF DIAGNOSIS IN DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS

Clinicians are also interested in how DCSs can facilitate the teaching and training of pediatricians and other professionals to diagnose and manage clinical problems. Relevant research questions include the interrater reliability and validity of the DCS, stability of diagnosis and prognosis over time, and the functional significance or validity of the diagnostic criteria.4

The complexity of the diagnosis and treatment of developmental and behavioral problems in children and adolescents presents significant challenges for any DCS. For example, children and adolescents present to clinical attention with an extraordinary number of developmental and behavioral problems that involve a wide range of symptoms that can affect functioning in different domains. The expression and severity of problems and symptoms vary dramatically as a function of the child’s age, as do normative developmental expectations for behaviors and symptoms.5 Moreover, the functional consequences of specific behavioral and developmental problems and diagnoses also vary widely in ways that may or may not be captured by a DCS.6 Finally, available scientific data concerning the validity of specific diagnostic categories also vary with DCSs and specific conditions.

SYSTEMS FOR DIAGNOSTIC CLASSIFICATION OF DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

A number of alternative DCSs can be used by clinicians with an interest in developmental and behavioral problems of children and adolescents to diagnose and treat these problems. We now describe several diagnostic classifications and their potential relevance to practice, teaching, and research.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)

HISTORY

The APA published a variation of the ICD-6 mental disorders categories in 1952, as the first edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), and it was first revised in 1967.7 Both of these editions were influenced predominantly by a psychoanalytic approach, and the term reaction was used for many of the disorders, more so in the first edition. For example, in 1967, what is now defined as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was still labeled hyperkinetic reaction of childhood. The classificatory structure was organized with two poles: psychosis on the severe end, characterized by a disconnection with reality and typically manifested by hallucinations, delusions, and illogical thinking, and neurosis at the mild end, characterized by distortions of reality and typically manifested by anxiety and depression.

In 1980, when the DSM was revised to the third edition,8 the psychodynamic view was discarded, and a biomedical model became the principal approach. The system included explicit diagnostic criteria and a multiaxial system. The revised system tried to make a clear distinction between normal and abnormal. The revision of the third edition, DSM-III-R,9 was published in 1987 and was based on additional research and consensus. It was subsequently revised again in 1994 as the fourth edition (DSM-IV),10 in part to develop compatibility between the DSM system and the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).11 Additional revisions in the text were published in 2000 without any substantial changes in the disorder characteristics (DSM-IV-TR).12

ORGANIZATIONAL PLAN

Axis I: Clinical Disorders and Other Conditions

The first axis consists of most of clinical mental disorders and other conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention. They are grouped into 16 major diagnostic classes. The first section is devoted to disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, and adolescence (Table 6-1). Communication Disorders; Pervasive Developmental Disorders; Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders; Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood; Tic Disorders; Elimination Disorders; and Other Disorders of Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence. However, some individuals with disorders that may be diagnosed during childhood (e.g., ADHD) may not present for clinical attention until adulthood. Moreover, it is not uncommon for the age at onset of many disorders in other sections (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder) to begin during childhood or adolescence. Significant controversy has arisen about when bipolar disorders are likely to manifest.13 Other diagnoses that are not specific to children but are applicable for children and adolescents include Anxiety, Mood Disorders, Eating Disorders, Somatoform Disorders, and Substance Use Disorders.

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association); NOS, not otherwise specified.

Axis II: Personality Disorders and Mental Retardation

Axis II, which includes Personality Disorders and Mental Retardation, is a carryover from the psychoanalytic concept separating permanent brain conditions from those caused by adverse childhood experiences. However, these distinctions have become much less clear with the subsequent finding of evidence of the importance of biological and genetic factors in the etiology of mental disorders and the contributions of environmental factors to Axis II as well as physical (Axis III) conditions. For instance, Autism Disorder is in Axis I even though it has much in common with Mental Retardation.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The DSM-IV manual also includes the following areas of additional information that may be important to diagnostic and treatment planning: (1) variations in the presentation of the disorder that are attributable to cultural setting, developmental stage (e.g., infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, late life), or gender (e.g., sex ratio); (2) prevalence, which includes data on point and lifetime prevalence, incidence, and lifetime risk as available for different settings; (3) course, which consists of typical lifetime patterns of presentation and evolution of the disorder: age at onset and mode of onset (e.g., abrupt or insidious) of the disorder; episodic versus continuous course; single versus recurrent episodes; and duration and progression (e.g., the general trend of the disorder over time); (4) familial pattern (e.g., data on the frequency of the disorder among first-degree biological relatives and family members in comparison with the general population); and (5) differential diagnosis.

CLINICAL USE AND LIMITATIONS

The occurrence of behavioral symptoms along a spectrum leads to much subjectivity in defining the boundaries of many disorders. The difficulty has been most prominent for ADHD, resulting in concerns about how many children receive a diagnosis of this condition14 and wide variations in the prevalence rates of how many children are being treated for the condition.15

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10)

HISTORY

In the early 1960s, the Mental Health Program of the World Health Organization worked to improve the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. These activities resulted in major revisions in the mental disorders, classified in the eighth edition. In both the eighth and ninth revisions, like DSM-II, the system contained the divisions between neurotic and psychotic disorders. However, the 10th edition (ICD-10), published in 1992,11 took a more atheoretical approach, similar to that of DSM-IV. The number of categories expanded from 30 in ICD-9 to 100 in ICD-10.

ORGANIZATIONAL PLAN

The mental disorders in ICD-10 are divided into ten categories: organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (F00-09); mental and behavioral disorders caused by psychoactive substance use (F10-19); schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F20-29); mood (affective) disorders (F30-39); neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40-49); behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F50-59); disorders of adult personality and behavior (F60-69); mental retardation (F70-79); disorders of psychological development (F80-89); and behavioral and emotional disorders with the onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (F90-98). The behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence and the disorders of psychological development are presented in Table 6-2.

TABLE 6-2 ICD-10: Behavioral and Emotional Disorders with Onset Usually Occurring in Childhood and Adolescence and Disorders of Psychological Development

|

Other specified behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence

|

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (World Health Organization).

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC), Child and Adolescent Version

HISTORY

Children demonstrate symptoms that vary along a continuum from normal variations to mental disorders, and this continuum can be subgrouped into normal developmental variations, problems, and disorders.

Children demonstrate symptoms that vary along a continuum from normal variations to mental disorders, and this continuum can be subgrouped into normal developmental variations, problems, and disorders. Environment has an important effect on the mental health of children, and if stressful situations are addressed, more severe mental health problems can be prevented.

Environment has an important effect on the mental health of children, and if stressful situations are addressed, more severe mental health problems can be prevented.ORGANIZATIONAL PLAN

The manual is divided into two major sections. The first section addresses the issue of a child’s environment, and the second section discusses a child’s manifestations of behavior. The preamble to the child’s environment “Situations Section” is provided to help the clinician describe and consider the effect of situations that present in practice and affect a child’s mental health. It also helps the clinician determine the potential consequences of an adverse situation and identify factors that may make a child more vulnerable or resilient and thus lessen or heighten the situation’s effect. The preamble is followed by a list of potentially adverse situations grouped by their nature, in which more common and/or well-researched situations are more specifically defined (Table 6-3). To help clinicians evaluate the effects of stressors, information concerning key risk and protective factors is provided. To help clinicians assess the effects of situations on the behavior of children, a table summarizes the common behavioral responses to stressful events for children of varying ages.

DSM-PC, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (American Psychiatric Association).

The second major section describes child manifestations, organized into behavioral clusters (Table 6-4). Because clinicians are usually first presented with concerns raised by children or their parents, an index of presenting complaints is also included. The clusters are also presented as an algorithm to facilitate the clinician’s ability to form a differential diagnosis. The design of each cluster was developed to help the primary care clinician evaluate (1) the spectrum of the child’s symptoms, (2) common developmental presentations, and (3) the differential diagnosis.

TABLE 6-4 DSM-PC: Classification of Child Manifestations

DSM-PC, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Primary Care (American Psychiatric Association).

HOW IS THE DSM-PC CURRENTLY BEING USED IN PRACTICE?

How the DSM-PC is currently being used in a range of settings is an important issue. To provide some preliminary information on this topic, Drotar and associates16 surveyed two groups, each of whom would be expected to be more knowledgeable about the DSM-PC and more likely to use it than the average group of professionals: (1) the Ohio Chapter of the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics (an interdisciplinary group of pediatricians, psychologists, and social workers) and (2) an interdisciplinary group consisting of the faculty trainers for DSM-PC. Professionals who reported using the DSM-PC were also asked to describe the advantages and disadvantages of the instrument. Most respondents believed that an advantage of the DSM-PC was its conceptualization of behavioral problems and the environmental contexts. Others reported that the developmental spectrum and the age-appropriate examples of symptom presentations were very useful and that the continuum of symptom severity and ability to label subsyndromal conditions was also an advantage. The primary disadvantage involved problems with reimbursement from third-party payers. Other disadvantages were lack of specificity or clarity of concepts outlined and an absence of guides to facilitate its use.16

CLINICAL APPLICATION: AN EXAMPLE FROM A PRIMARY CARE PRACTICE SETTING

To address the need for clinical application of the DSM-PC, Sturner and Howard17 developed a computerized version of a parent inventory known as the Child Health and Development Interactive System (CHADIS). In the inventory, parents are asked to identify their level of concern (very, somewhat, or not at all concerned) among a list of general concerns derived from the “presenting complaint” section of the DSM-PC Child Manifestations section. If more than one concern is identified, the parent is asked to prioritize among them. The parent is then prompted to respond to an algorithm of questions related to the identified chief complaint. The parent continues through the series of questions until (1) criteria for a diagnostic level are not achieved or (2) all the questions necessary to make a DSM-PC diagnosis have been reached. A pilot and feasibility study conducted with 27 children from a pediatric practice indicated positive parental reactions to participating in visits in which the CHADIS application of the DSM-PC was used.17 In several studies, Sturner and colleagues described the utility of the CHADIS system in identifying children in primary care who have DSM-PC diagnoses.18–20

Sturner and colleagues18 described the kinds of mental health problems documented by pediatricians during the course of child health supervision and the DSM-PC diagnoses made for the same children by the CHADIS. A convenience sample of inner-city children was seen by pediatricians for child health visits in two university-affiliated community pediatric clinics. After each visit, CHADIS/DSM-PC was administered to the child’s caregiver. Mental health diagnostic information documented on the clinic’s standard encounter forms was noted by two reliable coders. DSM-PC diagnoses were obtained from the CHADIS/DSM-PC. CHADIS/DSM-PC identified a “disorder” diagnosis in 27%, a “problem” in 28%, “developmental variation” in 21%, and no diagnosis for 23%. Pediatricians used a DSM-IV disorder label for 13% and informal diagnostic labels for another 10%.

INTERDISCIPLINARY USE

The DSM-PC can be a very useful tool for training psychologists and mental health professionals to understand the full range of clinical problems and environmental stressors among children when providing consultation to primary care physicians.4,21 Because the DSM-PC emphasizes the concept of a continuum of behavioral problems, it can be used to teach undergraduate and graduate students concepts of child development and developmental psychopathology.5

USE IN TARGETING AND MONITORING INTERDISCIPLINARY COMMUNITY-BASED PREVENTIVE INTERVENTION FOR CHILDREN AT RISK

The DSM-PC also provides a method for community-based service providers to categorize the types of environmental situations or stressors that might be expected to affect treatment planning and prognosis for at-risk children.16 For example, some children may receive early intervention services in response to specific environmental stressors (e.g., domestic violence or problems in caregiving) that are readily categorized by the DSM-PC.

RESEARCH

To our knowledge, Sturner and colleagues19 presented the first data on the validation of the DSM-PC, by using the previously described CHADIS/DSM-PC. Caregivers of children completed the CHADIS/DSM-PC and were assessed for DSM disorders through a computerized parent version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adults (DICA),22 measures of child behavioral symptoms,23 and competencies.24

No child with a diagnosis of DSM-PC Developmental Variation was found to have a disorder according to the DICA, and only two children in the problem category were shown to have a disorder on the DICA. Only one child who received no DSM-PC diagnosis was shown to have a DICA disorder. These results also supported the DSM-PC’s theoretical definitions for both Developmental Variations and Problems. For example, when parents raised concerns about behaviors that fall into the developmental variation category, the child’s behaviors were within the range of expected behaviors for the age and rarely warranted a diagnosis of mental disorder. This finding provides empirical support for the clinical utility of the developmental variations category.

Sturner and colleagues20 also described, on the basis of DSM-PC categories, the 1-year stability of children’s mental health status and morbidity in preschool- and school-aged children seen for health supervision visits at one of two Baltimore City clinics. Total scores used to represent mental health status (1 for each variation, 2 for each problem, 3 for each disorder) demonstrated excellent stability, as shown by a correlation of 0.69. Children with DSM-PC category diagnoses continued to show similar levels of morbidity 1 year later, whereas most children who received a diagnosis of a disorder persisted with the disorder. Moreover, most children who received an initial diagnosis of a problem either sustained the problem diagnosis or worsened. The Problem category demonstrated a positive predictive value of 0.71 for Problem or Disorder categories 1 year later, which provided evidence for the predictive utility of the DSM-PC categories.

Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood: Zero to Three (DC:03 and DC:03R)

HISTORY

Infants and young children present a particular challenge for diagnostic classification because of the rapid developmental change and fluidity of change during this developmental period. The DC:03 was developed to categorize the developmental and mental health problems of infants and young children for purposes of diagnosis and treatment planning by a wide range of practitioners. Expert, consensus-based categorizations of mental health and developmental disorders in the early years of life were developed by the Multidisciplinary Diagnostic Classification Task Force established by the Zero to Three National Center for Infants, Toddlers, and Families. This task force recognized that many infants and young children presented in practice situations with problems that could not be readily classified within the DSM-IV. The DC:03 was intended to complement and extend the DSM-IV as an initial guide for clinicians and researchers to facilitate clinical diagnosis, treatment planning, and research.25

The revision of the DC:03, the DC:03R, was developed on the basis of clinical experience and the findings of the Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria: Infancy and Preschool.26,27 The DC:03R provides clearer, more operational criteria than the original version as shown in Table 6-5.

DC:03R, Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood: Zero to Three revision (Zero to Three Revision Task Force); DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition; NOS, not otherwise specified.

ORGANIZATIONAL PLAN

Axis I: Clinical Disorders

This axis includes the following categories: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Deprivation/Maltreatment Disorder; Disorders of Affect; Prolonged Bereavement/Grief Reaction; Anxiety Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood; Depression of Infancy and Early Childhood; Mixed Disorder of Emotional Expressiveness; Adjustment Disorder; Regulation Disorders of Sensory Processing; Hypersensitive; Hyposensitive/Underresponsive; Sensory Stimulation–Seeking/Impulsive; Sleep Behavior Disorder; Sleep-Onset Disorder (Protodyssomnia) and Night-Waking Disorder (Protodyssomnia); Feeding Behavior Disorder; Disorders of Relating and Communication; Multisystem Developmental Disorder; and Other Disorders.

Axis IV: Psychosocial Stressors

Axis IV describes the nature and severity of psychosocial stress that are influencing disorders in infancy and early childhood. A specific instrument, the Psychological and Environmental Stressor Checklist,26 provides a framework for identifying (1) the multiple sources of stress experienced by individual effects on the young child and the family and (2) the duration and effect of stressors.

Axis V: Emotional and Social Functioning

The fifth axis reflects the infant or young child’s emotional and social functioning in the context of interaction with caregivers and in relation to expectable patterns of development. Relevant dimensions of emotional and social functioning in the DC:03R include the following: (1) Attention and Regulation; (2) Forming Relationships, Mutual Engagement; (3) Intentional Two-way Communication; (4) Complex Gestures and Problem Solving; (5) Use of Symbols to communicate; and (6) Connecting Symbols Logically. For each of these, the clinician may rate the child’s functioning on the 6-point Capacities for Emotional and Social Functioning Rating Scale.26

CLINICAL APPLICATION AND RESEARCH

Despite these potential advantages, the DC:03 has not been used extensively by either pediatricians or developmental-behavioral pediatricians in practice, in comparison with either the DSM-IV or the DSM-PC. Research on either the DC:03 or DC:03R has been very limited. Frankel and associates’27 chart reviews of children aged newborn to 58 months described the range and frequency of presenting symptoms, relationships between symptoms and diagnoses, and comparisons of the DC:03 and DSM-IV. Presenting symptoms were categorized into five groups: (1) Sleep Disturbances; (2) Oppositional and Disruptive Behaviors; (3) Speech and Language/Cognitive Delays; (4) Anxiety and Fears; and (5) Relationship Problems. Findings demonstrated interrater reliability for diagnoses with the use of both diagnostic systems, evidence of diagnostic validity through regression analyses, and good concordance for diagnoses in which the DSM-IV and DC:03 overlap.27

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY)

ORGANIZATIONAL PLAN

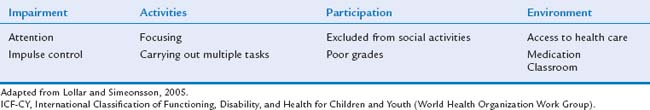

Available DCSs focus primarily on the categorizations of symptoms rather than on children’s functioning. To address the need to describe child and adolescent functioning with a common nomenclature, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) was developed for clinical practice, research, and policy development across disciplines and service systems.28 Key dimensions of this system include (1) impairments in body functions and in structured activities; (2) activity limitations; and (3) participation, defined as involvement in a life situation. In addition, the system describes environmental factors (e.g., the physical, social, and attitudinal settings in which individuals conduct their lives) and personal factors that affect functioning. A version of the ICF for children and youths (ICF-CY) has been developed.29 The ICF-CY includes more than 100 functional impairments and relevant codes that are applicable to DSM-IV, DSM-PC diagnostic categories, and the DC:03R. An example of the relevant dimensions and codes that are applicable to one disorder (ADHD) is shown in Table 6-6.

APPLICATIONS OF CLINICAL CARE, RESEARCH, AND POLICY

Lollar and Simeonsson30 discussed potential applications of the ICF-CY for developmental and behavioral problems in clinical care in describing activity limitations and access to care, for policy to define gaps in service, and for research concerning the functioning of children and adolescents and training.

One of the most important potential clinical applications of the ICF involves the facilitation of a common language and framework for professionals about impairment in functioning, diagnosis and treatment planning, and changes in these parameters.31 This common language facilitates professionals’ abilities to understand aspects of functional status or dysfunction in diagnosis and management of developmental and behavioral problems. For example, with ADHD, medication treatment might focus on addressing the child’s impairment in attention. In contrast, a psychologist’s behavioral intervention might focus on control of behavior and social relations. The ICF-CY system also provides a language for parents and various professional disciplines with which to communicate about goals for intervention and response to intervention.

Finally, the ICF-CY system also can be used to describe and manage the variations in the functioning of children with specific diagnoses. This is important in view of the considerable variation in the functional status of children who have specific behavioral and/or developmental disorders6 and the fact that such variation is often the focus of clinical attention. The clinical importance of functional status also highlights the need to better use measures of functioning31 in clinical practice. Finally, like the DSM-PC, the ICF-CY highlights the importance of including environmental factors in diagnosis and treatment planning.

Despite limited research on the ICF-CY system, emerging developments and opportunities32 include measures of critical dimensions that focus on school participation33 and assessment of activity limitations. For example, Fedeyko and Lollar34 used the ICF-CY to organize prevalence rates of activity limitations from the National Health Interview Survey, 1994–1995. Learning limitations were found to have the highest prevalence (9.4%) among children 5 to 17 years of age, followed by communication (4.8%) and behavior limitations (4.6%). Field trials are under way in the United States, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America to complete age-specific assessments of functional codes among different age groups (0 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 12, and 13 to 18).30

Perhaps the most important future applications of the ICF-CY focus on policy. The ICF-CY provides a common language with which to describe interdisciplinary clinical care and research on functional differences in children and adolescents across a range of settings.35 In addition, the ICF-CY can facilitate health care practitioners’, teachers’, and therapists’ communications about children’s functional status in response to psychological and medical interventions.30 The ICF-CY is a method that can be used to facilitate interdisciplinary care, research, and training31 across a wide range of different populations of children with behavioral and developmental disorders, impairments that result from these disorders, and settings in which these disorders are treated.

For all the diagnoses of mental disorders, impairment is part of the diagnostic criteria. In addition, the DSM-PC categories of problems and normal variations are defined by the extent of impairment. For this reason, the application of the ICF-CY provides an opportunity to define the metric by which the extent of impairment can be measured across different DCSs. It provides a construct on which a generalizable system of measurement of functional impairment can be developed. To accomplish this goal, measures must be developed and applied to specific chronic conditions,35 and modifications of the ICF-CY must be made in order to consider variations in the developmental levels of children and adolescents.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS IN CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

The future research related to DCS falls into one of two categories. The first category is research to document the validity and reliability of the systems. This issue is particularly important for the DSM-PC, DC:03, and the ICF-CY, for which new categories not defined previously were created. Studies need to include reliability, as well as concurrent and predictive validity. Some of the studies can be conducted globally for the overall system (e.g., Sturner et al20). However, some of the needed research should focus on specific diagnostic categories.

1 Wolraich ML. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC) Child and Adolescent Version: Design, intent, and hopes for the future. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18:171-172.

2 Rappo PD. Use of DSM-PC and implications for reimbursement. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18:175-177.

3 Coury DL, Berger SP, Stancin T, et al. Curricular guidelines for residency training in developmental-behavioral pediatrics. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20(2 Suppl):S1-S28.

4 Drotar D. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC), Child and Adolescent Version: What pediatric psychologists need to know. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24:369-380.

5 Sroufe LA, Rutter MC. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Dev. 1984;55:17-29.

6 Kazdin AE. Evidence-based assessment for children and adolescents: Issues in management development and clinical application. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34:548-558.

7 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1967.

8 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980.

9 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1987.

10 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

11 World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

12 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Text Revision

13 Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, et al. Current concepts in the validity, diagnosis and treatment of paedi-atric bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:293-300.

14 Diller LH. The run on Ritalin: Attention deficit disorder and stimulant treatment in the 1990s. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996;26(2):12-18.

15 LeFever G, Dawson KV, Morrow AL. The extent of drug therapy for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder among children in public schools. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1359-1364.

16 Drotar D, Sturner R, Nobile C. Diagnosing and managing behavioral and developmental problems in primary care: Applications of the DSM-PC. In: Wildman BG, Stancin T, editors. Treating Children’s Psychosocial Problems in Primary Care. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2004:191-224.

17 Sturner RA, Howard BJ, editors. The Child Health and Development System. Millersville, MD: Center for Promotion of Child Development through Primary Care, 2000.

18 Sturner R, Morrel T, Howard BJ. Mental health diagnoses among children being seen for child health supervision visits: Typical practice and DSM-PC diagnoses (Abstract in Pediatric Residence 441). Pediatric Academic Society, 2004.

19 Sturner R, Howard BJ, Morrel T, et al: Validation of a Computerized Parent Questionnaire for Identifying Child Mental Health Disorders and Implementing DSM-PC (Report 3801). Presented at the Pediatric Academic Society Meeting, San Francisco, 2003.

20 Sturner R, Morrel T, Howard BJ. DSM-PC diagnoses predict psychiatric morbidity one year later. Pediatric Academic Society. 2005;57:2711.

21 Drotar D. Consulting with Pediatricians: Psychological Perspectives. New York: Plenum Press, 1995.

22 Reich W. Diagnostic Interview with Children and Adolescents (DICA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:59-66.

23 Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, 2001.

24 Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:581-586.

25 Diagnostic Classification 0–3: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood. Washington, DC: Zero to Three, National Center for Infant Programs, 1994.

26 Zero to Three: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood. Washington, DC: Zero to Three Press, 2005.

27 Frankel KA, Boyum LA, Harmon RJ. Diagnoses and presenting symptoms in an infant psychiatry clinic: Comparison of two diagnostic systems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:578-587.

28 World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001.

29 World Health Organization. ICF Child-Youth Adaptation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004.

30 Lollar DJ, Simeonsson RJ. Diagnosis to function: Classification for children and youths. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;26:323-330.

31 Lollar DJ, Simeonsson RJ, Nanda U. Measures of outcomes for children and youth. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(12 Suppl 2):S46-S52.

32 Simeonsson RJ, Leonardi M, Lollar D, et al. Applying the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health to measure childhood disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:602-610.

33 Simeonsson RJ, Carlson D, Huntington GS, et al. Students with disabilities: A national survey. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:49-63.

34 Fedeyko HJ, Lollar DJ. Classifying disability data: A fresh integrative perspective. In: Altman BM, Barnartt SN, Hendershot GE, et al, editors. Using Survey Data to Study Disability: Results from the National Health Interview Survey on Disability Research in Social Science and Disability. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2003:55-72.

35 Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, et al. Linking health status measurements to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. J Rehabil Med. 2004;34:205-210.