CHAPTER 37 Diagnostic Arthroscopy: Indications, Portals, and Techniques

HISTORY

In 1932, Michael Burman concluded in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery that the elbow joint was “unsuitable for examination” arthroscopically.8 Since that time, advances in arthroscopy and equipment have made elbow arthroscopy safe and effective in the management of a variety of elbow disorders. Elbow arthroscopy is a technically demanding procedure that requires a thorough knowledge of the neurovascular anatomy of the elbow. The original indications for elbow arthroscopy only included the diagnosis and removal of loose bodies. As techniques have advanced, the indications for elbow arthroscopy have expanded to include the treatment of synovitis, osteochondritis dissecans, capsular contractures, arthritis, fractures, lateral epicondylitis, and instability.28,29,34,48

Elbow arthroscopy was originally performed with the patient in the supine position and the hand suspended to traction. Because of poor access to the posterior aspect of the elbow, Poehling et al.35 popularized the prone position for elbow arthroscopy. The lateral decubitus position has been advocated by O’Driscoll and Morrey.29 The arm is positioned with the involved side up, the elbow flexed at 90 degrees, and the arm supported by a padded bolster. This position allows better access to both anterior and posterior compartments.

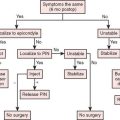

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The indications for elbow arthroscopy include the removal of loose bodies,7,18,23,26–28,40 removal of osteophytes secondary to osteoarthritis,25,30 radial head resection,20 release of capsular contractures and adhesions,9,14 and the resection of symptomatic plica.4,11 Other in-dications include the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans,6,28,37,42 fractures,3,24,28 lateral epicondylitis,5,44 instability,45 septic arthritis,48 synovectomy,3,48 and evaluation of patients with chronic elbow pain.28

Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of elbow arthroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of loose bodies. Success rates have been reported in the 90% range.7,18,26,27 Elbow arthroscopy for loose bodies is indicated in symptomatic patients who fail to respond to conservative treatment. The operating surgeon should attempt to determine the etiology of the loose body. Loose bodies are often a result of osteochondritis dissecans. Other causes include trauma, arthritis, or synovial osteochondromatosis. It is essential that the operating surgeon determines the source of loose bodies because the outcome of the patient will be determined by the disease, not just the removal of loose fragments.42

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

ANESTHESIA

Elbow arthroscopy can be performed under general or regional anesthesia. General anesthesia allows for complete muscle relaxation and flexibility of the patient.35 In an awake patient with regional anesthesia, the prone or lateral decubitus position may be poorly tolerated.17 Neurologic function can also be monitored postoperatively with general anesthesia alone.

Regional anesthesia with a scalene, axillary, or Beir intravenous regional block may also be used if the patient cannot undergo general anesthesia. The axillary block does not always achieve complete anesthesia about the elbow. Regional anesthesia may limit operative time secondary to longevity of the anesthetic agent or the intolerance of the patient to the tourniquet in a Beir block.

POSITIONING

Supine Position

In the supine position, first reported by Andrews and Carson3 in 1985, the patient lies supine with the shoulder over the edge of the operating table. The shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees and is in neutral rotation with 90 degrees of elbow flexion. The elbow is suspended by a traction device that is attached to either the hand or forearm (Fig. 37-1).

There are several advantages of the supine position in elbow arthroscopy.19,21 The supine position allows the anesthesiologist an easier access to the patient’s airway, and there is more flexibility to the choice of anesthesia. The conceptualization of the intra-articular anatomy is facilitated with the elbow in the supine position with the elbow joint in a more familiar anatomic orientation. Conversion of an arthroscopic procedure to an open procedure is readily facilitated in the supine position when required.

Prone Position

In response to the disadvantages of the supine position, Poehling and associates35 described the prone position for elbow arthroscopy. The patient is placed prone on the operating table over chest rolls to ensure adequate ventilation. The shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees, and the arm is supported by an arm positioner or an arm board (Fig. 37-2). The arm board is placed parallel to the operating table, centered at the shoulder. A sandbag, foam support, or rolled blankets are placed under the upper arm to elevate the shoulder and allow the elbow to rest in 90 degrees of flexion.

Advantages of the prone position are improved access and visualization of the posterior compartment of the elbow. Because the forearm hangs freely from the arm board, the elbow is easily manipulated from near full flexion to full extension. In the prone position, the anterior aspect of the elbow is facing inferiorly toward the floor, which allows neurovascular structures to fall anteriorly away from the joint. This provides an additional margin of safety when establishing portals. No special equipment or additional personnel are needed because the elbow position on the arm board is stable. The prone position, like the supine position, allows for easy conversion to an open procedure.39

Lateral Decubitus Position

The lateral decubitus position, first described by O’Driscoll and Morrey,29 combines the advantages of the supine and prone position while avoiding some of the pitfalls of each position. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position, with the arm positioned in an arm holder or over a bolster. The shoulder is flexed to 90 degrees and internally rotated, and the elbow flexed 90 degrees over a padded bolster (Fig. 37-3).

PORTALS

Surface landmarks are marked on the skin before creating portals. Important landmarks to outline are the radial head, olecranon, lateral epicondyle, medial epicondyle, and ulnar nerve. Before making portals, the joint must be distended with 20 to 30 mL of sterile saline (see Fig. 37-1). This can be done by placing an 18-gauge spinal needle either in the olecranon fossa or the soft spot bounded by the lateral epicondyle, olecranon, and radial head. Neurovascular structures are displaced away from the joint with distension of the joint, which gives an additional margin of safety.15,16

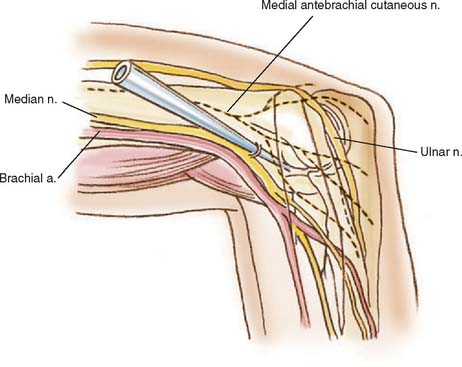

Proximal Anteromedial

Poehling and associates35 first described the proximal anteromedial portal in 1989. This portal is located 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and just anterior to the medial intermuscular septum (Fig. 37-4). The medial intermuscular septum is identified by palpation, and the portal is made anterior to the septum so that the ulnar nerve is not injured. The blunt trocar is introduced into the portal, anterior to the septum, and aimed toward the radial head while maintaining contact with the anterior surface of the humerus. This allows the brachialis muscle to remain anterior and protect the median nerve and brachial artery. The trocar enters the elbow through the tendinous origin of the flexor-pronator group and medial capsule.17

The proximal anteromedial portal has been recommended as the initial portal used with the patient in the prone or lateral decubitus position.15,35 This portal is thought to offer safer access and better visualization of the joint. In addition, fluid extravasation may be less with this portal compared with the anterolateral portal.15 Visualization of the entire aspect of the anterior aspect of the joint including the anterior capsule, trochlea, capitellum, coronoid process, radial head, and medial and lateral gutters can be obtained with this portal.

The primary structure at risk with this portal is the posterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutanenous nerve.46 This nerve is located approximately 2.3 mm from the trocar. With the elbow in flexion, the median nerve is relatively safe, protected by the brachialis muscle, being located on average a distance of 12.4 to 22 mm from the trocar.15,46 The path of the trocar aims distally and is in a parallel orientation to the median nerve making injury to the nerve less likely. The ulnar nerve is located on average a distance of 12 to 23.7 mm from the portal.15,46 The ulnar nerve is not at risk as long as the portal is made anterior to the intermuscular septum. Contraindications to the use of this portal are a history of subluxation or transposition of the ulnar nerve from its groove.15,32,46 Care must be taken to ensure that the ulnar nerve is not subluxed before anteromedial portal placement. This portal may be used in these circumstances only if the nerve is identified prior to trocar entry.

Anteromedial Portal

The anteromedial portal, first described by Andrews and Carson,3 is positioned 2 cm distal and 2 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 37-5). With the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, the blunt trocar is aimed at the center of the joint, passing through the flexor-pronator origin and the brachialis muscle before entering the joint capsule anterior to the medial collateral ligament. This portal may also be established by using an inside-out technique, with the arthroscope in the lateral portal.15 The entire anterior compartment of the elbow, especially the lateral structures, can be visualized from this portal. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is at greatest risk of being injured, located on average 1 mm from the portal.22,46 The median nerve is in closer proximity to this portal being located on average a distance of 7 to 14 mm.16,46 Lindenfeld15 reports an average distance of 22 mm from the portal to the median nerve if this portal is established 1 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle.

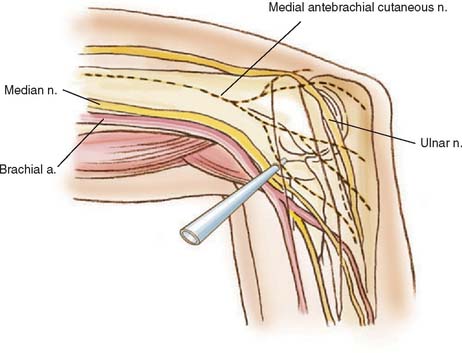

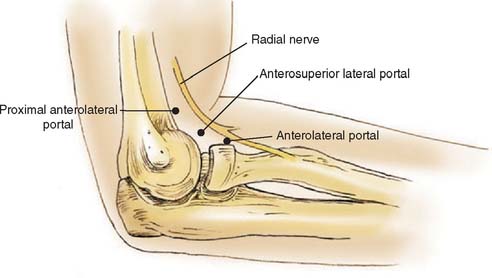

Proximal Anterolateral

The proximal anterolateral portal, described by Stothers and associates,46 Field and associates,12 and Savoie and Field41 is positioned 2 cm proximal and 1 to 2 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 37-6). This portal may be used as the initial portal in elbow arthroscopy. The blunt trocar is aimed towards the center of the joint while maintaining contact with the anterior humerus, and pierces the brachioradialis muscle, brachialis muscle and lateral joint capsule before entering the anterior compartment. This portal allows visualization of the anterior compartment, specifically the lateral and anterior aspects of the radial head and capitellum, lateral gutter, anterior ulnohumeral joint, and anterior elbow capsule.

The structures at risk on the lateral side are the posterior branch of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve and the radial nerve. The trocar in the proximal anterolateral portal lies on average 6.1 mm from the posterior branch of the antebrachial cutaneous nerve.46 This portal was developed because of the proximity of the radial nerve to the standard anterolateral portal. With the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion and distended with fluid, the radial nerve is located an average distance of 9.9 to 14.2 mm from the proximal anterolateral portal in contrast to 4.9 to 9.1 mm from the standard anterolateral portal.12,46

Anterolateral Portal

The standard anterolateral portal, first described by Andrews and Carson3 in 1985, is located 3 cm distal and 1 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle (see Fig. 37-6). The blunt trocar is aimed toward the center of the joint and passes through the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle and lateral joint capsule before entering the joint. This portal can also be established with an inside-out technique using the arthroscope in the anteromedial or proximal anteromedial portal. The arthroscope is advanced to the capsule lateral to the radial head. The arthroscope is then removed from the cannula and replaced with a blunt rod that tents the overlying skin. The skin is incised over the rod and a cannula is positioned over the rod and placed into the joint. It is imperative when using this technique that the blunt rod enters the capsule lateral to the radial head rather than anterior to it in order to avoid injury to the radial nerve.15,32,46

The anterolateral portal offers visualization of the anterior medial aspect of the joint including the coronoid process, trochlea, coronoid fossa, and medial aspect of the radial head. Visualization of the lateral joint is better with the proximal anterolateral portal.12 This portal is also useful as a working portal with the arthroscope in the proximal anteromedial portal, especially for procedures on the radial head.

Lynch and associates16 have shown the anterolateral portal to be located 2 mm from the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The radial nerve lies 4.9 to 9.1 mm from this portal with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion and the joint distended with fluid.12,46 Because of its proximity and increased risk to the radial nerve, most authors recommend a more proximal entry for this portal.

Midlateral Portal

Instrumentation of the lateral gutter and posterior radiocapetellar joint may be used with this portal. There is minimal risk to neurovascular structures with this portal. The posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve, approximately 7 mm away,1 is the only structure at risk. Because of leakage of fluid into the soft tissues, it is advisable to delay this portal until the end of the operation.32,34,46

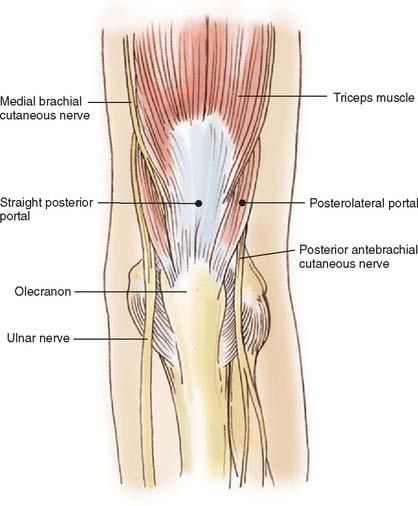

Straight Posterior Portal

The straight posterior or transtriceps portal is located 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon in the midline posteriorly33,34 (Fig. 37-7). This portal allows visualization of the entire posterior compartment, as well as the medial and lateral gutters.17 The blunt trocar is advanced toward the olecranon fossa through the triceps tendon and posterior joint capsule. With the arthroscope in the posterolateral portal, the straight posterior portal can be used for distal humeral fenestration with a drill or burr in ulnohumeral arthroplasty to access the anterior compartment of the elbow.32 This portal may also be used for instrumentation in removal of loose bodies and excision of olecranon spurs.17

Posterolateral Portal

The posterolateral portal is located 3 cm proximal to the olecranon tip and just lateral to the triceps tendon (see Fig. 37-7). The blunt trocar is advanced toward the olecranon fossa, passing lateral to the triceps tendon to enter the joint through the posterolateral capsule. This is performed with the elbow held in 45 degrees of flexion in order to relax the triceps and posterior capsule.46 Triceps tendon injury can be avoided by remaining close to the posterior humeral cortex with the blunt trocar. This portal is approximately 20 mm from the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and 25 mm from the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve.16 The posterolateral portal allows excellent visualization of the posterior compartment of the elbow as well as medial and lateral gutters. In examining the medial gutter from this portal, the operating surgeon must be aware of the location of the ulnar nerve, which lies just superficial to the medial capsule.32,35

Posterolateral II Portal

Access to the posterolateral aspect of the elbow can be obtained anywhere between the soft spot portal to the standard posterolateral portal, 3 cm proximal to the olecranon tip. This portal is usually placed just lateral to the olecranon process and can be moved proximally or distally as needed. Visualization through this portal usually consists of distally the posterior radiocapitellar joint and proximally across the olecranon into the olecranon fossa. It may be used for excision of lateral olecranon spurs, resection of posterolateral plica, and débridement of the radial aspect of the ulnohumeral joint. The triceps tendon and ulnohumeral cartilage are at risk with placement of this portal.41

PROCEDURE

General anesthesia is administered, and the patient is placed in the prone position on the operating table over chest bolsters to ensure adequate ventilation. All bony prominences are well padded, and the shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees. An arm board is placed parallel to the operating table and a sandbag is positioned under the arm to elevate the shoulder. The forearm is allowed to fall over the arm board with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. A Mayo stand with the appropriate instruments are placed next to the surgeon and scrub nurse, while the video monitor and equipment are placed on the opposite side of the patient. A tourniquet is placed on the upper part of the arm and an esmarch is used to exsanguinate the extremity. Once the arm is prepped and draped, surface landmarks of the elbow are outlined including the medial and lateral epicondyle and the olecranon process (Fig. 37-8). Also the ulnar nerve is specifically palpated to confirm that it remains in the cubital tunnel and is not subluxated. An 18-gauge spinal needle is next placed into the straight posterior or soft spot portal, and 20 to 30 mL of sterile saline is injected into the joint. This usually results in slight extension of the elbow as the joint space is filled.

With the arthroscope in the proximal anteromedial portal the entire anterior compartment of the elbow can be evaluated. From lateral to medial this includes examination of the lateral gutter, capitellum, radial head, anterior capsule, trochlea, coronoid process, and if properly placed, medial gutter. The arthroscopic evaluation initially includes inspection of the radiocapitellar joint through a range of motion in pronation and supination. This is performed to ensure that the radial head is congruent with the capitellum and that no subluxation exists and to evaluate the articular cartilage of the radial head. The arthroscope is then advanced anterior to the radiocapitellar joint, and the lens is rotated to visualize the capsule and undersurface of the extensor muscles. The ulnohumeral articulation is next evaluated by retracting and rotating the arthroscope so that the coronoid process is in view. By rotating the lens superiorly, the attachment of the capsule to the humerus is visible.

FIGURE 37-9 The two standard posterior portals most commonly utilized in the elbow are delineated in this figure.

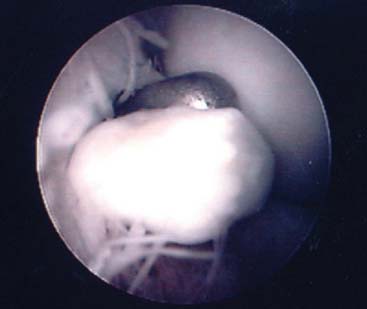

Loose bodies are commonly found in the anterior compartment in the coronoid fossa (Fig. 37-10). Once the loose body is identified, a lateral portal is established using a spinal needle. For removing loose bodies the proximal anterolateral portal is preferred. The spinal needle is placed 2 cm proximal and 1 to 2 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle, aiming toward the center of the joint. Once intra-articular placement is confirmed arthroscopically, the spinal needle is removed and a No. 11 blade knife is used to incise skin only in order to avoid damage to cutaneous nerves. A blunt trocar and cannula is then advanced into the joint while maintaining contact with the anterior humerus to avoid injury to the radial nerve. A grasper with teeth is introduced into the proximal anterolateral portal and used to remove the loose bodies. It may be necessary to “pin or stab” the loose body with an 18-gauge spinal needle, inserted through the mid anterolateral or anteromedial portal site, in order to provide resistance for grasping. The loose body should be rotated as it is being brought through the soft tissue so that it does not get lost. For larger loose bodies the portal may have to be enlarged in order to accommodate the size of the fragment. Otherwise, the loose body may need to be removed piece by piece.

FIGURE 37-10 These loose bodies may be removed from an anterolateral portal using a grasping device.

Once the loose bodies in the anterior compartment are removed, the posterior compartment is addressed. The cannula in the proximal anteromedial portal is left in place, and the inflow is attached so that the loose bodies are pushed to the posterior compartment. In the posterior compartment, loose bodies are usually located in the olecranon fossa (Fig. 37-11). The straight posterior portal is established using a No. 11 blade knife 3 cm proximal from the olecranon process and in the midline posteriorly. The blunt trocar and cannula are directed toward the olecranon fossa. Once loose bodies are identified, the posterolateral portal is established by placing a spinal needle 3 cm proximal to olecranon process and lateral to the triceps. Once the spinal needle is determined to be in the appropriate position arthroscopically, a No. 11 blade knife is used to incise only skin and a blunt trocar and cannula are introduced into the posterior compartment. Usually a motorized shaver is necessary to débride soft tissue in order to obtain full access to the olecranon fossa. The loose bodies can be removed from either the straight posterior or posterolateral portal. The tip of the olecranon should be carefully evaluated because this is often a source for loose bodies. The arthroscope is next directed toward the medial gutter. Using the opposite hand, the surgeon applies pressure in an alternating fashion to the soft tissues posterior to the medial epicondyle in a distal to proximal direction. This maneuver should “milk” any loose bodies from the medial gutter. “Hidden” loose bodies are often found in the posterolateral gutter.

TECHNICAL ALTERNATIVES AND PITFALLS

Loose body removal from the elbow is the most successful and ideal indication for elbow arthroscopy. The success of the procedure often depends on the cause of the loose body. Most pitfalls in elbow arthroscopy relate to damage to neurovascular structures with a prevalence ranging from zero to 14%2,13,16,31,33,36,38 in the literature. Most nerve injuries are transient and can be caused from extravasation of fluid or local anesthestic,3 compression from the arthroscopic sheaths, direct injury from the trocar, or overaggressive joint distension. Injury to the radial, median, anterior interosseous, medial antebrachial cutaneous, and ulnar nerves have been reported.3,10,16,31,36,38,43,47 In a review of 473 consecutive elbow arthroscopies, Kelly and associates13 found 10 patients (2.5%) with transient nerve palsies.

Many nerve injuries are associated with the use of the anterolateral and anteromedial portals because of their close proximity to neural structures. The radial nerve, posterior interosseous nerve, and superficial branch of the radial nerve have been injured during placement of the anterolateral portal.16,31,47 Injuries of the median and anterior interosseous nerves during placement of the anteromedial portal have been reported.3,16,38 Neuroma formation can result from injury of the superficial cutaneous nerve.16

In order to avoid nerve injuries, knowledge of neurovascular anatomy and careful portal placement are critical. The prone position allows neurovascular structures to fall anteriorly, away from the joint. Fluid distension of the joint and flexing the elbow to 90 degrees have been documented to increase the distance between neurovascular structures and portals.15,16 When making a portal, the knife blade should cut only through skin. The skin should drag across the blade instead of making a stab incision. This prevents injuries to the superficial cutaneous nerves.

Other complications in elbow arthroscopy are iatrogenic articular cartilage injury, infection, persistent drainage of portals, synovial fistula formation, and problems associated with the tourniquet. Complications such as arthrofibrosis, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and thromboembolism are seen less frequently.43

OUTCOMES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Probably one of the most successful operations in elbow arthroscopy is removal of symptomatic loose bodies. Several authors have reported on the beneficial effects of removal of loose bodies. As mentioned previously, the physician should attempt to determine the cause of the loose bodies. In many cases, simply removing loose fragments will not improve the outcome of the patient. This point is illustrated by O’Driscoll and Morrey’s28 review of 71 elbow arthroscopies in which 24 elbows had loose bodies. Fourteen patients with a primary diagnosis of loose bodies and another four patients with loose bodies secondary to osteochondritis dissecans improved after arthroscopic removal of their loose bodies. Patients with loose bodies secondary to post-traumatic arthritis, primary degenerative disease, synovial chondromatosis, or idiopathic flexion contracture did not improve with simple removal of loose bodies.

1 Aldolfsson L. Arthroscopy of the elbow joint: A cadaveric study of portal placement. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:53.

2 Andrews J.R., Baumgarten T.E. Arthroscopic anatomy of the elbow. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1995;26:671.

3 Andrews J.R., Carson W.G. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97.

4 Antuna S.A., O’Driscoll S.W. Snapping plicae associated with radiocapitellar chondromalacia. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:491.

5 Baker C.L.Jr, Murphy K.P., Gottlob C.A., Cuerd D.T. Arthroscopic classification and treatment of lateral epicondylitis: two-year clinical results. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg.. 2000;9:475.

6 Baumgarten T.E., Andrew J.R., Satterwhite Y.E. The arthroscopic evaluation and treatment of osteochondritis desiccans of the capitellum. Am. J. Sports Med. 1998;26:520.

7 Boe S. Arthroscopy of the elbow: Diagnosis and extraction of loose bodies. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1986;57:52.

8 Burman M. Arthroscopy of the elbow joint: a cadaver study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1932;14:349.

9 Byrd J.W. Elbow arthroscopy for arthrofibrosis after type I radial head fractures. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:162.

10 Casscells S.W. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: inherent risks [Editor’s comment]. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:190.

11 Clarke R. Symptomatic lateral synovial fringe of the elbow joint. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:112.

12 Field L.D., Altchek D.W., Warren R.F., O’Brien S.J., Skyhar M.J., Wickiewicz T.L. Arthroscopic anatomy of the lateral elbow: A comparison of three portals. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:602.

13 Kelly E.W., Morrey B.F., O’Driscoll S.W. Complications in elbow arthroscopy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2001;83:25.

14 Jones G.S., Savoie F.H. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:277.

15 Lindenfield T.N. Medial approach in elbow arthroscopy. Am. J. Sports Med. 1990;18:413.

16 Lynch G.J., Meyers J.F., Whipple T.L., Caspari R.B. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: Inherent risks. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:191.

17 Lyons T.R., Field L.D., Savoie F.H. Basics of elbow arthroscopy. Instruct. Course Lect. 2000;49:239.

18 McGinty J. Arthroscopic removal of loose bodies. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1982;13:313.

19 McKenzie P.J. Supine position. In: Savoie F.H., Field L.D., editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:35.

20 Menth-Chiari W.A., Ruch D.S., Poehling G.G. Arthroscopic excision of the radial head: Clinical outcome in 12 patients with post-traumatic arthritis after fracture of the radial head or rheumatoid arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:918.

21 Meyer J.F., Carson W.G.Jr. Elbow arthroscopy: Supine technique. In: McGinty J.B., Burkhart S.S., Jackson R.W., Johnson D.H., Richmond J.C., editors. Operative Arthroscopy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippencott-Raven; 2003:665.

22 Miller C.D., Jobe C.M., Wright M.H. Neuroanatomy in elbow arthroscopy. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:168.

23 Morrey B.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Instruct. Course Lect. 1986;35:102.

24 Moskal J.H., Savoie F.H., Field L.D. Elbow arthroscopy in trauma and reconstruction. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1999;30:163.

25 O’Driscoll S.W. Arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Orthop. Clin North Am. 1995;26:691.

26 O’Driscoll S.W. Elbow arthroscopy for loose bodies. Orthopaedics. 1992;15:855.

27 O’Driscoll S.W. Elbow arthroscopy: loose bodies. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:510.

28 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow: Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1992;74:84.

29 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993:120.

30 Ogilvie-Harris D.J., Gordon R., MacKay M. Arthroscopic treatment for posterior impingement in degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:437.

31 Papilion J.D., Neff R.S., Shall L.M. Compression neuropathy of the radial nerve as a complication of elbow arthroscopy: a case report and review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:284.

32 Plancher K.D., Peterson R.K., Breezenoff L. Diagnostic arthroscopy of the elbow: Set-up, portals, and technique. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 1998;6:2.

33 Poehling G.G., Ekman E.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Instruct. Course Lect. 1995;44:217.

34 Poehling G.G., Ekman E.F., Ruch D.S. Elbow arthroscopy: Introduction and overview. In: McGinty J.B., Caspari R.B., Jackson R.W., Poehling G.G., editors. Operative Arthroscopy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:821.

35 Poehling G.G., Whipple T.L., Sisco L., Goldman B. Elbow arthroscopy: a new technique. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:222.

36 Rodeo S.A., Forester R.A., Weiland A.J. Neurologic complications due to arthroscopy. J. Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:917.

37 Ruch D.S., Cory J.W., Poehling G.G. The arthroscopic management of osteochondritis dissecans of the adolescent elbow. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:797.

38 Ruch D.S., Poehling G.G. Anterior interosseous nerve injury following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:756.

39 Rubin C.J. Prone or lateral decubitus position. In: Savoie F.H., Field L.D., editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:41.

40 Savoie F.H. Arthroscopic management of loose bodies of the elbow. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 2001;9:241.

41 Savoie F.H., Field L.D. Anatomy. In: Savoie F.H., Field L.D., editors. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:3.

42 Savoie F.H., Field L.D. Basics of elbow arthroscopy. Tech. Orthop. 2000;15:138.

43 Small N.C. Complications in arthroscopy: the knee and other joints. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:253.

44 Smith A.M., Castle J.A., Ruch D.S. Arthroscopic resection of the common extensor origin: anatomic considerations. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:375.

45 Smith J.P.3rd, Savoie F.H., Field L.D. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Clin. Sports Med. 2001;20:47.

46 Stothers K., Day B., Reagan W.R. Arthroscopy of the elbow: Anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:449.

47 Thomas M.A., Fast A., Shapiro D.L. Radial nerve damage as a complication of elbow arthroscopy. Clin. Orhop. Relat. Rel. 1987;215:130.

48 Wiesler E.R., Poehling G.G. Elbow arthroscopy: introduction, indications, complications, and results. In: McGinty J.B., Burkhart S.S., Jackson R.W., Johnson D.H., Richmond J.C., editors. Operative Arthroscopy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2003:661.