Chapter 15 Diagnosis of Restless Legs Syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS), like most syndromes, represents multiple biological pathologies that share a common clinical presentation. As such, the diagnosis of RLS relies almost entirely on the subjective report of symptoms matching the defining features of RLS. Nonetheless, the nonspecific but sensitive objective motor signs of RLS—periodic limb movements while lying resting awake (PLMW) and while asleep (PLMS)—provide important support for the diagnosis. Given the critical nature of the clinical presentation, after a brief review of the historical development of the diagnosis, this chapter explores the clinical aspects of the defining features. The four clinical features that define RLS appear to be simple enough, but clinicians commonly misunderstand them and fail to appreciate some of their specific expressions. Accurate diagnosis starts with a full understanding of these four defining features as they manifest in RLS. The diagnosis can be further aided by three supportive features of RLS and by recognition of differing RLS phenotypes. This chapter ends with the presentation of tools that have been developed to support making the RLS diagnosis.

History

What appears to be the earliest description of RLS in the medical literature by Willis1,2 in the 17th century emphasizes both the abnormally excessive movements and their occurrence during usual sleep times. References to RLS after Willis appear to largely assign RLS to a psychiatric or psychological disorder (e.g., related to anxiety3 or, more specifically, financial worries4) until the middle of the 20th century, when Ekbom5 described the presentation of the disorder in a large series of cases. His work both provides the name currently used for the disorder and establishes RLS as a neurologic disorder. Ekbom emphasized the sensory aspects (paresthesias in the legs) of the disorder6 more than the motor features (contractions of the legs) described by Willis. Even after this excellent work, RLS remained largely ignored until the latter part of the 20th century, when a small group of clinicians treating RLS patients formed the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) and developed the first clinical consensus on the diagnosis of RLS.7 These diagnostic criteria restored the emphasis on the movement aspects of RLS and in particular noted an urge to move the legs often but not always associated with the paresthesias. There remained some confusion in the criteria established by this group, particularly in relation to the concept of “restlessness.” These issues were resolved in a National Institutes of Health workshop where the current diagnostic standards were developed.8 Thus, as shown in Box 15-1, the RLS diagnosis has evolved from observed movements to the recognition of the akathisia focused in the legs and modulated by diagnostically significant factors.

BOX 15-1 Evolution of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Diagnosis

| Willis (1685) | Movement and sleep disruption described |

| Ekbom (1945) | Sensory disturbance emphasized |

| American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) (1990) | Sensory and periodic leg movement disturbance of sleep, nocturnal worsening emphasis |

| International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) (1995) | Restores emphasis on movement as “restlessness” |

| Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation/IRRLSG/National Institutes of Health Workshop (2002) | Final formulation of diagnostic standards |

| Emphasis on “urge to move,” removes motor restlessness and separates effects of rest and activity; clears up some concepts related to supportive features |

Essential Diagnostic Criteria

All four of the diagnostic criteria given in Box 15-2 must be met to make the diagnosis of RLS, and failure to meet any one of these excludes the RLS diagnosis. These four criteria appear deceptively simple, but further examination reveals several subtle aspects embedded in these diagnostic features.

BOX 15-2 Essential Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Diagnostic Criteria

All four of the following criteria must be met to make the diagnosis of RLS:

TABLE 15-1 Activities to Reduce Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Symptoms Compared With Those to Stay Awake

| Reduce RLS Symptoms | Stay Awake |

|---|---|

| 1. Movement | 1. Movement |

| Sitting up helps very little | Sitting up helps very little |

| Standing helps some | Standing helps some |

| Walking, moving help a lot | Walking, moving help a lot |

| 2. Intense conversation—argument | 2. Intense conversation—argument |

| 3. Eating food | 3. Eating food |

| 4. Hard rubbing of the legs (or arms) | 4. Hard rubbing of the body |

| 5. Very hot or cold baths | 5. Bracing (hot or cold) shower or bath |

Features Supporting the Diagnosis

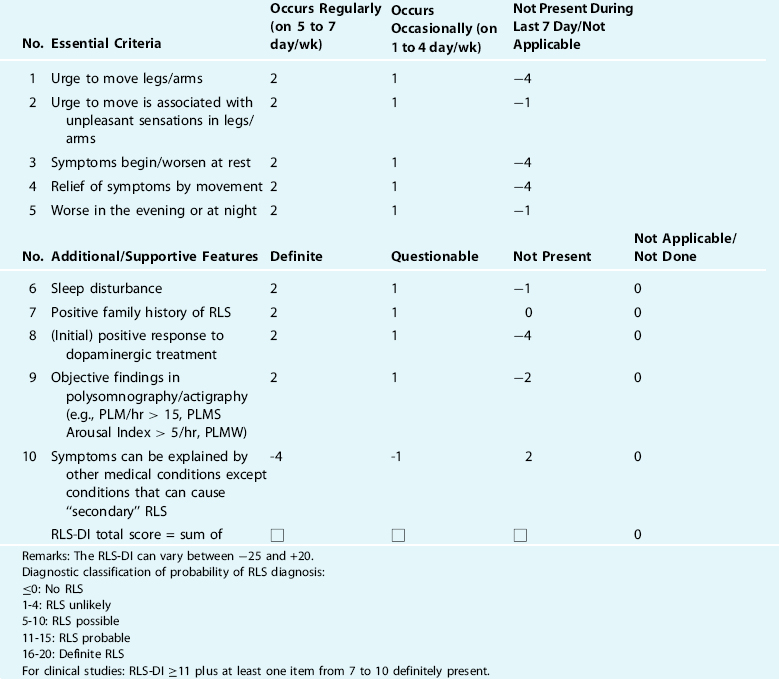

In addition to the essential diagnostic criteria, there are three features of RLS presented in Box 15-4 that provide support for the diagnosis. These are particularly helpful for establishing a diagnosis when there is some uncertainty about the essential diagnostic criteria. They also inform about the disorder, and one provides a method for objective evaluation of change in symptom severity.

Phenotypes of Restless Legs Syndrome

In addition, a small set of cases has been reported with all the symptoms of RLS and involuntary leg movements but not the urge to move and in some cases neither the urge to move nor the abnormal sensations. These have been called quiescegenic nocturnal dyskinesias.30 They probably do not involve the same pathology as RLS or may involve some overlap of pathology with RLS with added pathologic features producing this phenotypic variant of RLS.

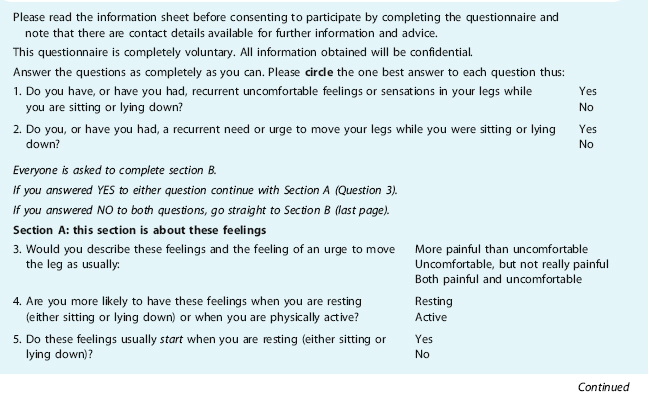

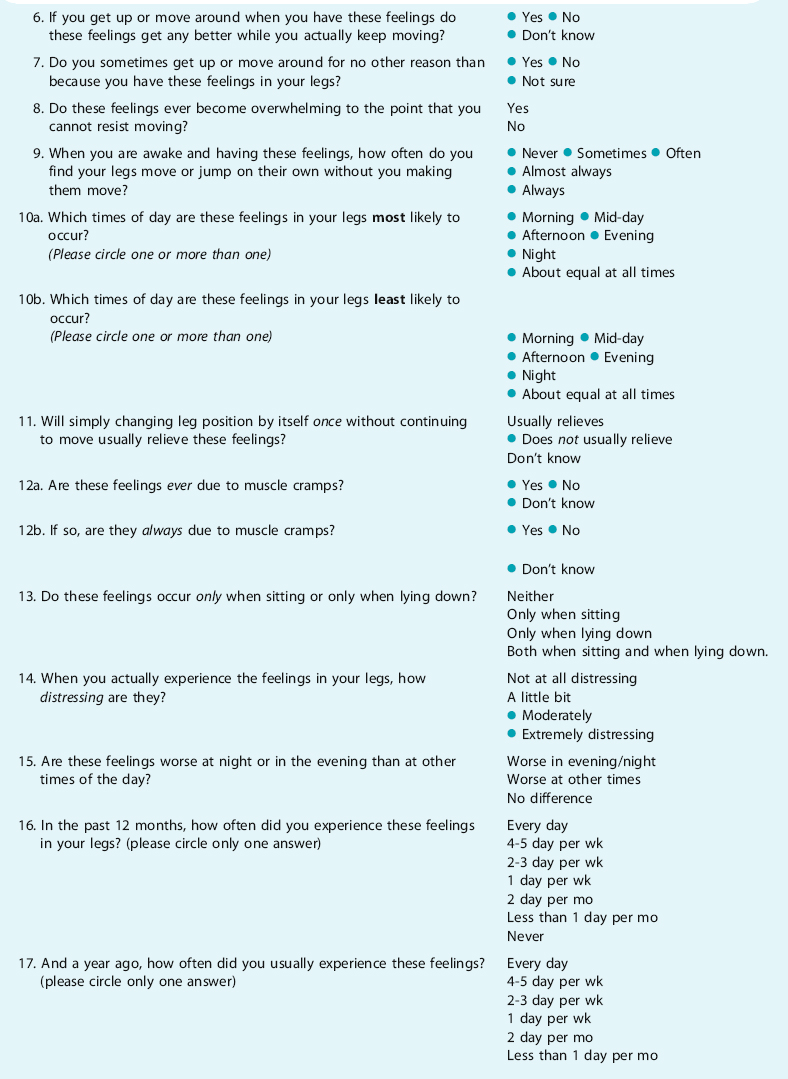

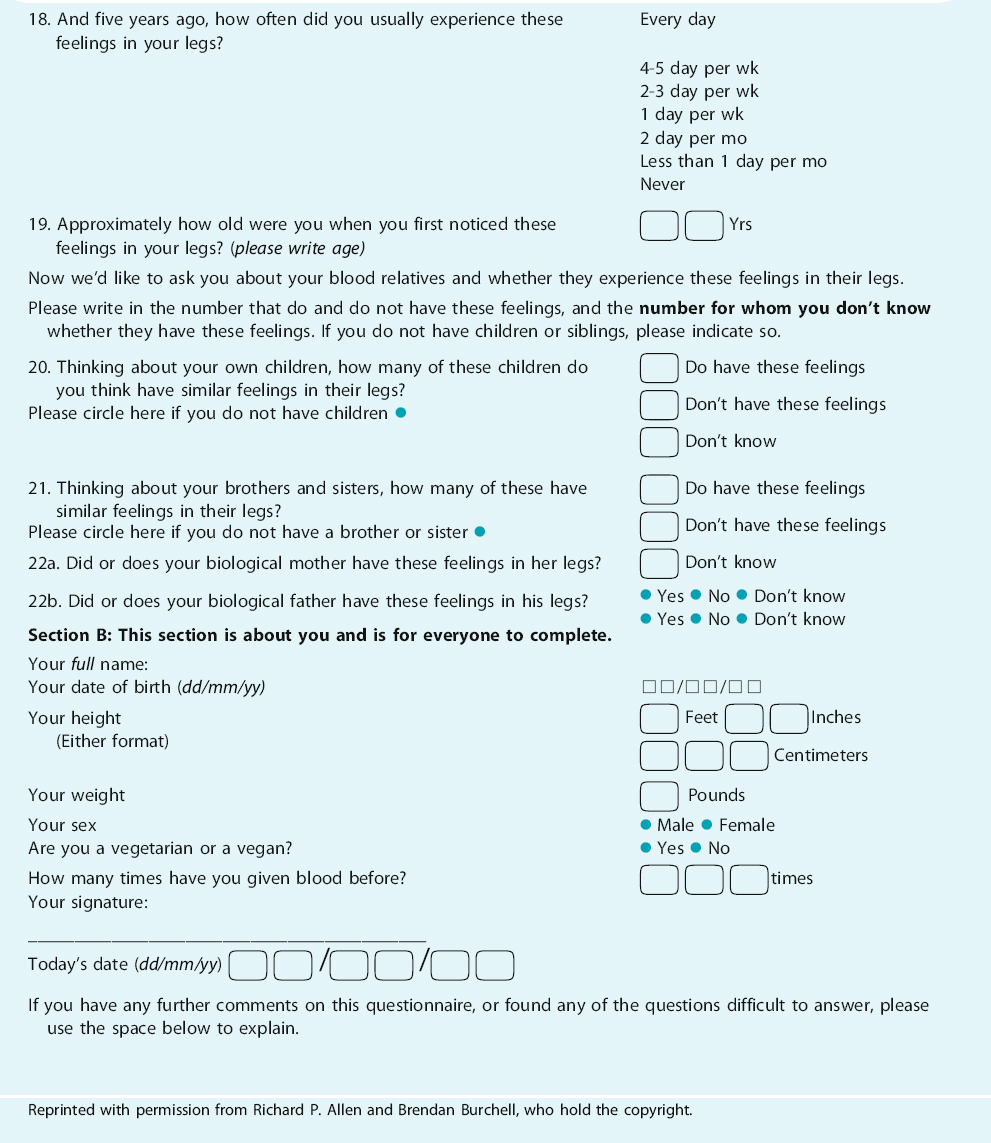

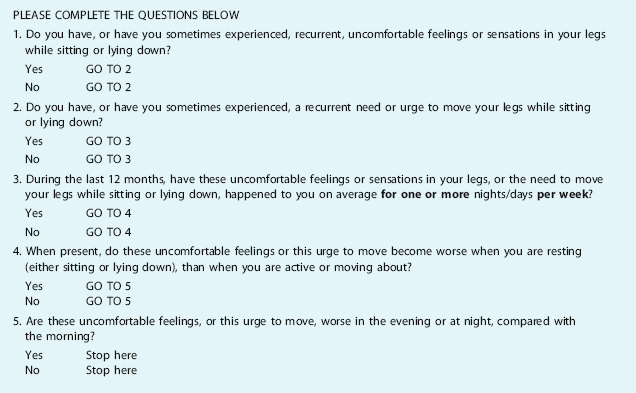

Tools Aiding Diagnosis

TABLE 15-3 Five RLS Diagnostic Questions Used In Several Major Survey Studies (Note that the questionnaire could be altered so the subject stops if the response is no to question 2 and question 1)

If you have any further comments on this questionnaire, or found any of the questions difficult to answer, please use the space below to explain.

Reprinted with permission from Richard P. Allen and Brendan Burchell, who hold the copyright.

Summary

The fundamental concept for diagnosing RLS relies on recognizing the three basic features of this syndrome. First, the fundamental symptom of a focal akathisia must be present and expressed by the patient in some appropriate fashion. The verbal or behavioral expression of this may vary with age and cultural background, but in the end the urge to move focused on, even arising from, the legs must be established to make the diagnosis of RLS. Second, this must clearly be expressed in relation to degree of arousal or sleepiness. Thus, it must not occur when doing very alerting activities such as walking, and it must occur when in the predormitum state before the entry to sleep. This interesting resting-awake state receives very little attention in sleep medicine or neurology, but RLS essentially expresses itself in this state. Remember in evaluating the patient that any increase in arousal should reduce symptoms and any decrease in arousal may induce the symptoms. Actual movement is only one aspect of the physical and mental activation that relieves symptoms. Finally, the symptoms manifest with a dramatic circadian pattern characterized by increasing severity in the evening and night but even more by a relative protected period around 8 A.M. to 10 A.M., when symptoms become rare or, at most, much diminished.

The clinical picture of the patient should also be generally consistent with the degree of severity of the reported symptoms and the age at onset of the symptoms. The patient’s response to factors that almost always exacerbate RLS, like sitting in crowded, cramped quarters (theater or airplane) or taking dopamine agonists or sedating antihistamines, can help confirm uncertain diagnoses. The supportive features noted above can also help. The definition of the RLS phenotype suffices for good diagnostic agreement certainly as good or better than other conditions like depression or fibromyalgia that, like RLS, rely largely on clinical history and subjective symptoms for the diagnosis.

1. Willis T. The London Practice of Physick. London: Bassett and Crooke, 1685.

2. Willis T. De Animae Brutorum. London: Wells and Scott, 1672.

3. Wittmaack T. Pathologie und Therapie der Sensibilität-Neurosen. Leipzig: E. Schäfer, 1861.

4. Code CF, Allen EV. Neurosis involving the legs: report of three illustrative cases. Proc Staff Meet. Mayo Clin. 1936;11:60-62.

5. Ekbom KA. Restless Legs. Stockholm: Ivar Haeggströms, 1945.

6. Ekbom KA. Asthenia crurum paraesthetica (“irritable legs”). Acta Med Scand. 1944;118(1-3):197-209.

7. Walters AS, Aldrich MA, Allen RP, et al. Towards a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

8. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

9. Bassetti CL, Mauerhofer D, Gugger M, et al. Restless legs syndrome: A clinical study of 55 patients. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:67-74.

10. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Nicolas A, et al. Immobilization tests and periodic leg movements in sleep for the diagnosis of restless leg syndrome. M128 Disord. 1998;13:324-329.

11. Michaud M, Lavigne G, Desautels A, et al. Effects of immobility on sensory and motor symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2002;17:112-115.

12. Allen RP, Dean T, Earley CJ. Effects of rest-duration, time-of-day and their interaction on periodic leg movements while awake in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6:429-434.

13. Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Walters AS, et al. Circadian rhythm of periodic limb movements and sensory symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1999;14:102-110.

14. Hening WA, Walters AS, Wagner M, et al. Circadian rhythm of motor restlessness and sensory symptoms in the idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1999;22:901-912.

15. Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Moller JC, et al. Validation of the “L-DOPA test” for diagnosis of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1333-1339.

16. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: A study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61-65.

17. Montplaisir J, Michaud M, Denesle R, Gosselin A. Periodic leg movements are not more prevalent in insomnia or hypersomnia but are specifically associated with sleep disorders involving a dopaminergic impairment. Sleep Med. 2000;1:163-167.

18. Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:510-514.

19. Birinyi PV, Allen RP, Hening WA, et al. Undiagnosed individuals with first-degree relatives with restless legs syndrome have increased periodic limb movements. Sleep Med. 2006;7:480-485.

20. Michaud M, Paquet J, Lavigne G, et al. Sleep laboratory diagnosis of restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2002;48:108-113.

21. Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, de la Llave Y, et al. Correlation between rating scales and sleep laboratory measurements in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2004;5:561-565.

22. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Validation of the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Severity Scale. Sleep Med. 2001;2:239-242.

23. Sforza E, Haba-Rubio J. Night-to-night variability in periodic leg movements in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6:259-267.

24. Allen RP, La Buda MC, Becker P, Earley CJ. Family history study of the restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2002;suppl:S3-S7.

25. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Defining the phenotype of the restless legs syndrome (RLS) using age-of-symptom-onset. Sleep Med. 2000;1:11-19.

26. Walters AS, Hickey K, Maltzman J, et al. A questionnaire study of 138 patients with restless legs syndrome: The ‘Night-Walkers’ survey. Neurology. 1996;46:92-95.

27. Winkelmann J, Muller-Myhsok B, Wittchen HU, et al. Complex segregation analysis of restless legs syndrome provides evidence for an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance in early age at onset families. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:297-302.

28. Earley CJ, Connor JR, Beard JL, et al. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and restless legs syndrome: Effects of different clinical phenotypes. Sleep. 2005;28:1069-1075.

29. Earley CJ, Barker PB, Horská A, Allen RP. MRI-determined regional brain iron concentrations in early and late-onset restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:458-461.

30. Lesage S, Allen RP, Earley CJ. Quiescegenic nocturnal dyskinesia (QND): A newly recognized sleep-related movement disorder sometimes confused with restless legs syndrome [abstract]. Sleep. 2004;suppl:27.

31. Hening W, Allen RP, Thanner S, et al. The Johns Hopkins telephone diagnostic interview for the restless legs syndrome: Preliminary investigation for validation in a multi-center patient and control population. Sleep Med. 2003;4:137-141.

32. Hening WA, Allen RP, Washburn M, et al. Validation of the Hopkins telephone diagnostic interview for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007. Epub Jul 16

33. Benes H, Kohnen R. Personal communication.

34. Benes H, Kohnen R. Validation of an algorithm for the diagnosis of restless legs syndrome: the restless legs syndrome-diagnostic index (RLS-DI). Sleep Med, in press.

35. Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:196-202.

36. Berger K, von Eckardstein A, Trenkwalder C, et al. Iron metabolism and the risk of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population—The MEMO Study. J Neurol. 2002;249:1195-1199.

37. Hening W, Walters AS, Allen RP, et al. Impact, diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a primary care population: The REST (RLS epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment) primary care study. Sleep Med. 2004;5:237-246.

38. Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286-1292.

39. Nichols DA, Kushida CA, Allen RP, et al. Validation of RLS diagnostic questions in a primary care practice. Sleep. 2003;26:A346.

40. Ferri R, Lanuzza B, Cosentino FII, et al. A single question for the rapid screening of restless legs syndrome in the neurological clinical practice. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:1016-1021.

41. Hening WA, Sharon D, Abraham M, et al. Validation of a single question screener question for the restless legs syndrome [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2006;21:S443.