Patient history 88

4.1. Patient history

4.1.1. Course of the disease

4.1.2. Localization

4.1.3. Trauma

4.1.4. Load, posture, and position

4.1.5. Non-mechanical factors

4.1.6. Psychological factors

4.1.7. Paroxysmal character

4.1.8. The significance of patient age

4.2. The inspection: posture

4.2.1. The dorsal aspect

Further details to examine are:

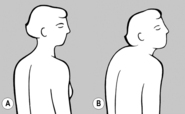

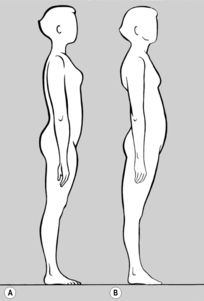

4.2.2. The lateral aspect

Cervical lordosis largely depends on the shape of the thoracic spine. If the thoracic spine is flat, cervical lordosis may be completely absent. This is particularly seen in individuals of the athletic type with broad shoulders and a flat thoracic cage; similarly in ballet dancers. If the back is round, on the other hand, the thoracic kyphosis often continues into the lower cervical spine, with only the upper part of the cervical spine showing lordosis.

4.2.3. The ventral aspect

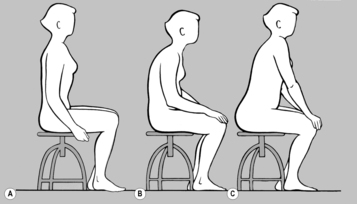

4.2.4. Inspection of the seated patient

4.3. Palpation (soft-tissue examination)

4.3.1. Hyperalgesic zones

A small area of skin can be examined by stretching it between the fingertips (the interdigital folds are an example) – a larger area is examined between the thumbs and the palms of the hands – always taking up the slack until the point where the barrier is engaged, and always comparing one side with the other (see Figure 6.56).

4.3.2. Subcutaneous tissue and fasciae

The scalp also behaves in the same way as a fascia relative to the skull.

4.3.3. Trigger points

|

| Figure 4.1 |

|

| Figure 4.2 |

| Muscle | Clinical significance |

|---|---|

| Soleus | Pain at the Achilles tendon |

| Quadriceps femoris | Lesion in L4 segment; pain at the upper edge of the patella; ‘pseudo hip and/or knee pain’ |

| Tensor fasciae latae | Pain at the hip and at the superior border of the patella |

| Thigh adductors | Lesion in the hip joint; TrP in pelvic region |

| Iliacus | Lesion in S1 segment; coccyx; pseudovisceral pain |

| Piriformis | Lesion in L5 segment; ‘hip pain’ |

| Ischiocrural muscles | Lesion in segments L5, S1 (straight-leg raising test positive); pain at the ischial tuberosity and head of the fibula |

| Levator ani | Pain at the coccyx |

| Coccygeus | Low back pain; many chain reactions due to pelvic floor dysfunction |

| Erector spinae | Back pain in the corresponding segment |

| Psoas major | Pseudovisceral pain; restricted rotation of trunk |

| Quadratus lumborum | Acute lumbago; restricted rotation of trunk |

| Rectus abdominis | Tenderness at xiphoid process and pubic symphysis; pseudovisceral pain |

| Pectoralis major | Pain at chest wall; pseudocardiac pain |

| Pectoralis minor | Tender coracoid process, sternocostal joints, and superior thoracic aperture |

| Diaphragm | Chest pain; cervical syndrome |

| Transverse (middle) part of trapezius | Cervicobrachial and radicular syndromes |

| Subscapularis | Pain in the shoulder; in the arm; at the lesser tubercle; pseudocardiac pain |

| Supraspinatus, infraspinatus | Pain in the shoulder; in the arm; at the greater tubercle |

| Supinator, biceps brachii, forearm extensors | Radial (lateral) epicondylopathy |

| Triceps brachii | Pain in the axilla; epicondylopathy |

| Finger flexors | Ulnar (medial) epicondylopathy |

| Descending (superior) part of trapezius | Neck pain; headache and shoulder pain |

| Levator scapulae | Shoulder pain; headache; neck pain |

| Scalene muscles | Pain at Erb’s (supraclavicular) point; at the superior thoracic aperture |

| Craniocervical extensors | Upper cervical syndrome |

| Sternocleidomastoid | All cervical syndromes |

| Masticatory muscles | Earache; upper cervical syndrome |

4.3.4. Periosteal pain points

| Periosteal point | Clinical significance |

|---|---|

| Head of metatarsals | Metatarsalgia in the case of splay foot; also in the case of tarso-metatarsal restriction |

| Calcaneal spur | TrP of deep plantar flexors |

| Head of fibula | TrP in biceps femoris, tibialis posterior; restriction of fibular head; forward-drawn posture |

| Pes anserinus (tendinous expansions of muscles at medial border of tuberosity of tibia) | TrP in the hip adductors; osteoarthritis of hip joint |

| Insertion of collateral ligament | Lesion of a meniscus in the knee |

| Superior border of patella | TrP in quadriceps femoris and tensor fasciae latae |

| Ischial tuberosity | TrP in the ischiocrural muscles |

| Posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) | Frequent but not specific |

| Lateral border of the pubic symphysis | TrP in the hip adductors; hip |

| Superior border of the pubic symphysis | TrP in the rectus abdominis; forward-drawn posture |

| Coccyx | TrP in the levator ani, tension in the gluteus maximus |

| Iliac crest | TrP in the gluteus medius and quadratus lumborum |

| Pain at spinous process | Hypermobility with TrP in the erector spinae muscles |

| Spinous process T4—T6 | Weakest region of erector spinae with TrP |

| Spinous process of C2 | Lesion in segments C2—C4; TrP in levator scapulae |

| Xiphoid process | TrP in rectus abdominis |

| Ribs in the medioclavicular line | TrP in pectoralis minor |

| Ribs in the axillary line | TrP in the serratus anterior |

| Sternoclavicular joint | TrP in the scalene muscles and superior parts of the pectoralis muscles |

| Sternum just below 1st rib | Sternocostal joint of 1st rib |

| Angle of ribs | TrP in subscapularis; restriction of ribs |

| Sternal end of clavicle | TrP in sternocleidomastoid |

| Pain at Erb’s point | TrP in scalene muscles; radicular syndromes |

| Transverse processes of atlas | TrP in sternocleidomastoid |

| Posterior margin of foramen magnum | Restriction of retroflexion at C0/C1; headache; migraine |

| Nuchal line | Referred pain from the short craniocervical extensors, insertion of splenii capitis muscles |

| Condylar process of mandible | TrP in masticatory muscles |

| Hyoid | TrP in digastric and mylohyoid muscles |

| Styloid process of radius | Lesion of the radioulnar joint |

| Radial (lateral) epicondyle | TrP in biceps, supinator, extensor muscles of the fingers |

| Ulnar (medial) epicondyle | TrP in flexor muscles of the fingers |

| Attachment of deltoid | TrP in deltoid; frozen shoulder |

4.3.5. Radicular syndromes

Unless these signs are present we may suspect root lesion, but this requires further proof.

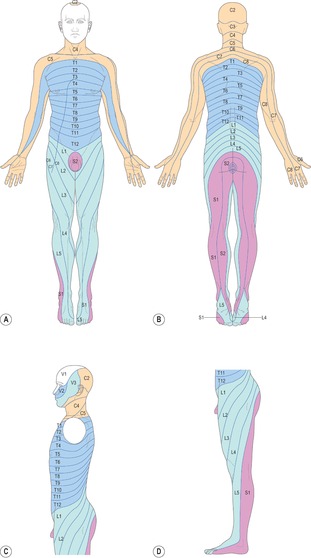

|

|

| Figure 4.3

The dermatomes. (A) Ventral aspect. (B) Dorsal aspect. (C) Lateral aspect of the trunk (after Hansen & Schliack 1962). (D) Lateral aspect of the lower limb (after Keegan 1944). (E) The perineum (after Hansen & Schliack 1962).

|

4.3.6. Conclusion

4.4. Mobility testing

4.4.1. Active mobility

4.4.2. Movement against resistance

4.4.3. Passive mobility

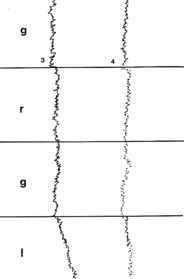

Figar & Krausová (1975) were able to measure the resistance to springing using a resistance transducer. This was done in a restricted cervical segment before treatment, during manipulation, and after treatment (see Figure 4.4).

The spinal column

The lumbar spine

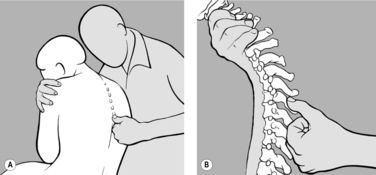

The cervical and thoracic spine

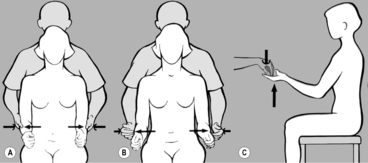

4.5. Examination of the pelvis

4.5.1. Screening examination

Inspection

Deviation of the upper end of the intergluteal cleft to one side is the result of asymmetrical positioning of the inferior end of the sacrum and coccyx.

Palpation

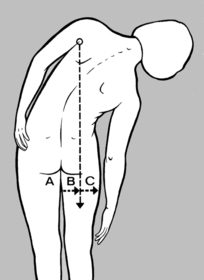

4.5.2. Pelvic obliquity

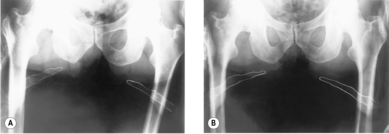

The patient should be asked each time whether it is more comfortable with the heel insert, or whether it feels awkward. If the patient finds at the very least that the (unaccustomed!) heel insert does not feel awkward, the effect is seen to be favorable. Equalization of length can then be recommended, unless of course the patient has one flat foot. An X-ray check (with patient standing) is recommended to confirm the difference in leg length.

4.5.3. Pelvic distortion

4.5.4. Pelvic tilt

4.5.5. Restriction of the sacroiliac joint

Testing for ‘overtake’

The spine sign test

|

| Figure 4.7 |

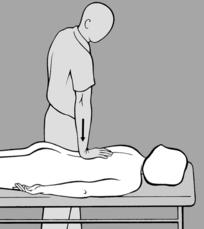

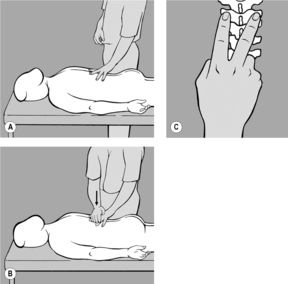

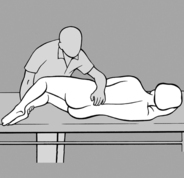

Springing test with patient supine

Springing test with patient in the side-lying position

Springing test with patient prone

|

| Figure 4.10 |

Test technique according to Rosina

Pain points

4.5.6. Shear dysfunction (Greenman) (upslip and downslip)

4.5.7. Outflare and inflare

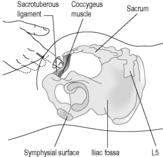

4.5.8. The pelvic floor and coccygeus muscle

4.5.9. The painful coccyx

4.5.10. Ligament pain

|

| Figure 4.13 |

4.6. Examination of the lumbar spine

4.6.1. Screening examination of active movement

Retroflexion

Side-bending

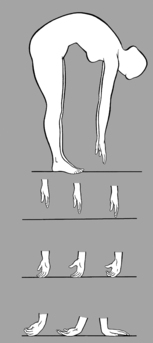

Anteflexion

4.6.2. Examination of individual motion segments

Palpation

Springing test

Palpation of mobility

Retroflexion

Anteflexion

Side-bending

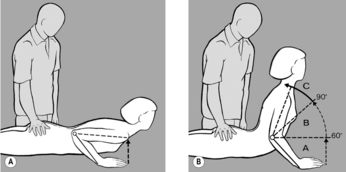

4.7. Examination of the thoracic spine

4.7.1. Screening examination of active movement

4.7.2. Palpation of mobility

Retroflexion

|

| Figure 4.21 |

4.7.3. Anteflexion

|

| Figure 4.22 |

4.7.4. Side-bending

|

| Figure 4.23 |

4.7.5. Rotation

4.8. Examination of the ribs

4.8.1. Screening examination

|

| Figure 4.25 |

4.8.2. Examination of the first rib

|

| Figure 4.26 |

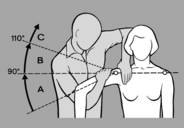

4.9. Examination of the cervical spine

4.9.1. Screening examination

4.9.2. Examination of passive mobility

Retroflexion and anteflexion

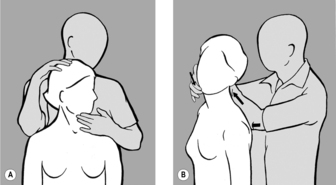

Side-bending

Rotation

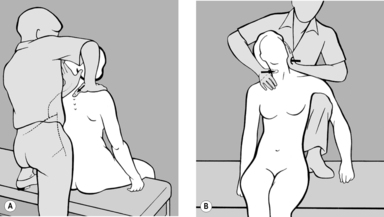

Examination with patient sitting

With the head in maximum anteflexion

With maximum forward nutation of the head

In retroflexion

4.9.3. Examination of the motion segments

Side-bending

With patient supine

With patient sitting

With patient in the side-lying position

|

| Figure 4.31 |

Rotation

|

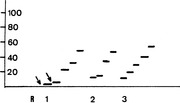

| Figure 4.33

Step diagram produced using cervicomotography according to Berger (1990). 1, Movement restriction between C1/C2 and C2/C3 (arrows), and hypermobility between C3/C4. 2, After mobilization, restriction between C2/C3 and hypermobility between C3/C4. 3, Normal finding after further treatment.

|

Shifting techniques

This technique can be used to examine the segments from C2/C3 down to C5/C6 backward and to the side. It can also be used successfully, in the backward direction only, to test the occiput–atlas segment. In this case slight anteflexion of the head is advisable. The fixing hand grasps around the arch of the axis, but shifting is only possible between the atlas and the occipital condyles, not between the atlas and axis.

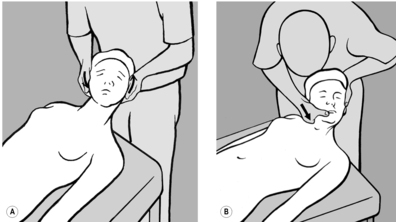

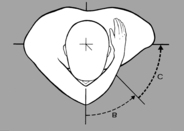

4.9.4. Testing of mobility between occiput and atlas

Anteflexion

Side-bending

Retroflexion

Rotation

4.10. Examination of the limb joints

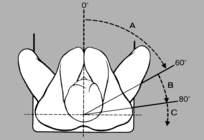

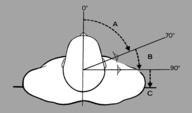

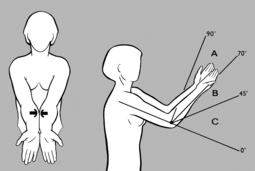

4.10.1. The shoulder

Active movement

Passive movement

External rotation

Internal rotation

Abduction

The acromioclavicular joint

The sternoclavicular joint

4.10.2. The elbow

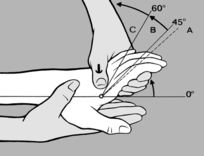

4.10.3. The wrist

The metacarpophalangeal joints are in fact ball and socket joints, which permit movement in every plane, but the absence of rotator muscles means that only flexion, extension, and laterolateral movements are actively possible. The only exception is the saddle joint between the trapezium and first metacarpal. This joint permits movement in all three planes, whereas the first metacarpophalangeal joint only permits flexion and extension.

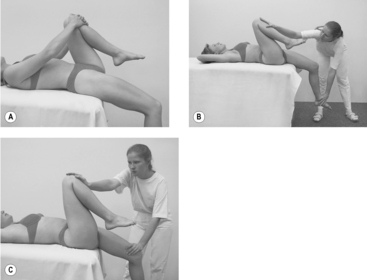

4.10.4. The hip

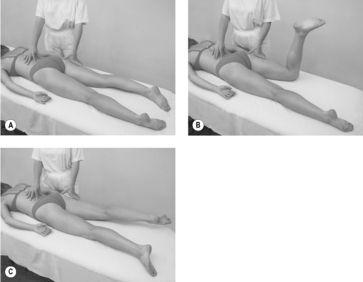

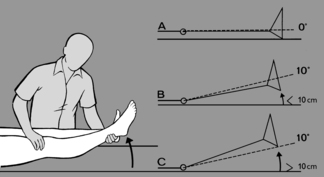

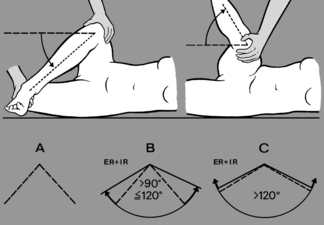

|

| Figure 4.43 |

|

| Figure 4.44 |

4.10.5. The knee

Again, asymmetry here can cause pelvic obliquity.

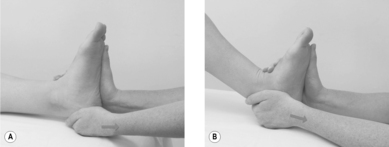

4.10.6. The foot

4.11. Examination of the temporomandibular joint

4.12. Examination of disturbances of balance

4.13. Examination of muscle function

4.13.1. General principles

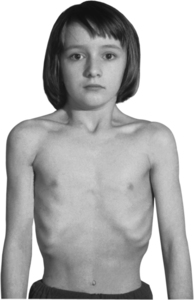

Clinical kinesiological examination

In the neurological examination the signs of special interest are those characteristic of minimal brain damage, such as marked asymmetry, especially of the face and the limbs, restlessness, clumsiness, agitation, and also minor deficits such as slight paresis, hypesthesia, and paresthesia.

Evaluation of muscle function

Our patients are for the most part seeking treatment for painful conditions, and none of them apart from those with radicular syndromes are suffering from true paresis; consequently the values we find range between grades 4 and 5, and only the abdominal muscles and deep neck flexors occasionally exhibit weakening to grade 3. As a result, the degree of distinction that can be made using grades 4 and 5 is not fine enough to be useful for the assessment of our patients.

Some modification of the muscle function test therefore are helpful for our patients, who do not suffer from paresis. The most important techniques are described below. In the sections dealing with muscular stereotypes (see 2.9 and 4.15), a distinction is made in line with the work of Janda between those muscles with a tendency to weakness and laxity and those with a tendency to hyperactivity and shortening.

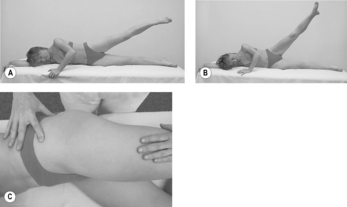

4.13.2. Examination of muscles with a tendency to weakness

The gluteus maximus

The gluteus medius

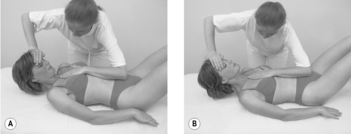

The rectus abdominis

|

| Figure 4.49 |

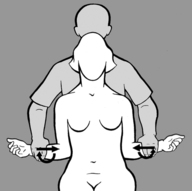

The transversus abdominis

The inferior (ascending) part of the trapezius

The serratus anterior

The deep flexors of the neck

4.13.3. Examination of muscles with a tendency to shortening

The soleus

The ischiocrural muscles

The hip flexors

The lumbar erector spinae

The quadratus lumborum

|

| Figure 4.57 |

The muscles of the nuchal region

|

| Figure 4.58 |

4.14. Examination of hypermobility

I also compare Sachse’s criteria with the data given by Kapandji (1974) and describe the technique.

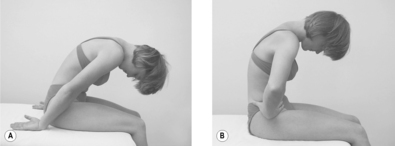

4.14.1. The spinal column

The lumbar spine

Retroflexion

Anteflexion

Side-bending

Rotation

The thoracic spine

Rotation

Anteflexion, retroflexion, and side-bending

The cervical spine

Rotation

4.14.2. The joints of the upper limb

The metacarpophalangeal joints

The elbow

The shoulder

4.14.3. The joints of the lower limb

The knee

The hip

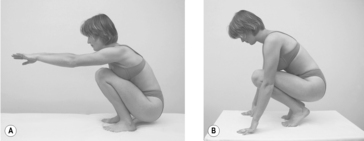

4.15. Examination of coordinated movements (motor stereotypes)

4.15.1. Examination with the patient sitting

|

| Figure 4.71 |

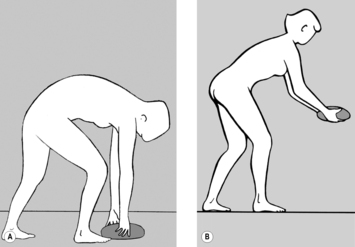

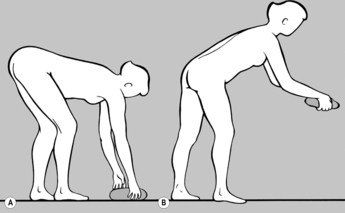

Anteflexion: stooping and straightening

Trunk rotation, sitting

|

| Figure 4.74 |

Rotation of the head and neck

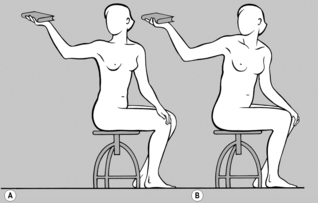

Raising the arms

4.15.2. Examination with the patient standing erect

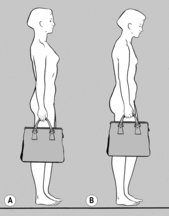

Weight carrying

Standing on one leg

Gait

4.15.3. Movement patterns of respiration

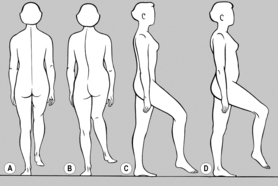

The close relationship between posture and respiration can be seen not least in the effect of a hunched sitting posture, which makes it difficult for the thoracic cage to expand and so leads to clavicular breathing. This kyphotic posture is associated with a forward-drawn position of the head, which is compensated by hyperlordosis of the cervical spine.

4.16. Syndromes

4.16.1. The lower crossed syndrome

There is also substitution for the weak gluteus maximus by the ischiocrural and erector spinae muscles, for the gluteus medius by the tensor fasciae latae and quadratus lumborum, and for the rectus abdominis by the hip flexors.

|

| Figure 4.79 |

4.16.2. The upper crossed syndrome

The ascending part of the trapezius is extremely important for the fixation of the scapula. Activity of this muscle portion can produce reflex relaxation of the upper fixators. Tension of the pectoralis muscles leads to increased thoracic kyphosis and forward-drawn shoulders, as well as kyphosis of the lower part and hyperordosis of the upper part of the cervical spine.

4.16.3. Stratification syndrome (according to Janda)

4.17. Retesting

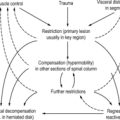

4.18. Dysfunctions and the course of examination

4.19. Adjusting our thinking to the functional approach

The following points present in general terms the most important differences between the usual, pathomorphological understanding and the functional approach.

4.20. Chain reactions of dysfunctions and motor programs

4.20.1. Function and chain reactions

The chain reactions of dysfunction envisaged here are given in Table 4.3. These do not claim to be complete; although these are the chains especially affected, the disturbance is not limited to the details listed. The intention is rather to provide some means of screening. Our understanding is further focused and extended by our insight into developmental kinesiology.

| Lower limb — gait — swing phase – extension | |

| Tension | Flexors of toes and foot, soleus, ischiocrural muscles, glutei, piriformis, levator ani, erector spinae |

| Painful points of attachment | Calcaneal spur, Achilles tendon, fibular head, ischial tuberosity, coccyx, iliac crest, greater trochanter of femur, spinous processes of L4—S1 |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Small joints of foot, ankle joint, fibular head, sacro-iliac joint, lower lumbar spine, (atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints) |

| Lower limb — gait — stance phase — flexion | |

| Tension | Extensors of toes and foot, tibialis anterior, hip flexors, hip adductors, recti abdominis, thoracolumbar erector spinae |

| Painful points of attachment | Pes anserinus of tibia, patella, lesser trochanter of femur, superior border of pubic symphysis, xiphoid process |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Knee, hip, sacroiliac joint, superior lumbar spine, thoracolumbar junction (atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints) |

| Trunk — body statics | |

| Tension in muscle pairs | Sternocleidomastoid and short craniocervical extensors |

| Scalenes+deep neck flexors+digastric and: trapezius+levator scapulae+masticatory muscles | |

| Iliopsoas+recti abdominis and: erector spinae+quadratus lumborum | |

| Painful points of attachment | Posterior arch of atlas, spinous process of C2, nuchal line, sternal end of clavicle, superior and medial border of scapula, xiphoid process, pubic symphysis, lower ribs, iliac crest |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints, cervicothoracic junction and upper ribs, thoracolumbar junction (trunk rotation), lumbosacral and sacroiliac junction, temporomandibular joint |

| Lifting the thorax during inhalation (clavicular breathing) | |

| Tension | Superior parts of abdominal muscles, pectoralis, scalene, diaphragm, sternocleidomastoid muscles, short craniocervical extensors, levator scapulae, superior part of trapezius |

| Painful points of attachment | Posterior arch and transverse processes of atlas, spinous process of C2, nuchal line, sternal end of clavicle, superior border of scapula, sternocostal joints and upper ribs |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints, cervicothoracic junction, upper ribs, thoracic spine |

| Upper limb — prehension — restricted flexion | |

| Tension | Extensors of fingers and wrist, thenar eminence, supinator, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, upper fixators of scapula, interscapular muscles |

| Painful points of attachment | Radial styloid process, radial (lateral) epicondyle, attachment of supraspinatus and infraspinatus, attachment of levator scapulae, spinous process of C2 |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Elbow, acromioclavicular joint, middle cervical spine, cervicothoracic junction, upper ribs |

| Upper limb — prehension — restricted extension | |

| Tension | Flexors of fingers and wrist, pronators, subscapularis, pectoralis, sternocleidomastoid, scalene muscles |

| Painful points of attachment | Ulnar (medial) epicondyle, sternal end of clavicle, sternocostal joints, Erb’s point, transverse process of atlas |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Carpal bones, elbow, glenohumeral joint, cervicothoracic junction, atlanto–occipital and atlanto-axial joints |

| Head and neck — eating — speaking | |

| Tension | Masticatory, digastric, sternocleidomastoid muscles, craniocervical extensors, trapezius, levator scapulae, deep neck flexors, pectoralis muscles |

| Painful points of attachment | Hyoid, posterior arch and transverse processes of atlas, spinous process of C2, nuchal line, sternal end of clavicle, superior border of scapula, angle of upper ribs |

| Joint dysfunction (restrictions) | Temporomandibular joint, atlanto–occipital and atlanto-axial joints, cervicothoracic junction, upper ribs |

4.20.2. Chain reactions in the light of developmental kinesiology

|

| Figure 4.80

EMG of the deltoid muscle and diaphragm on raising the arm: contraction of the diaphragm takes place in advance of contraction of the deltoid (modified after Richardson et al 2004). Pdi, transdiaphragmatic pressure; Pga, intra-abdominal pressure; Poes, intrathoracic pressure.

|