34 Diagnosis and Treatment of Malignant and Premalignant Lesions

For melanoma, risk factors include family history, large congenital nevi, the familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome (FAMMS; previously dysplastic nevus syndrome) (Figure 34-1) and sun exposure, particularly blistering burns in fair-skinned individuals. After initial biopsy, Breslow’s classification by depth of invasion is used to guide re-excision margins and the need for sentinel lymph node biopsy and to predict general survival rates.

Actinic Keratoses, Actinic Cheilitis, and Bowen’s Disease

Actinic keratoses (AK), actinic cheilitis, and Bowen’s disease (SCC in situ) are all caused by cumulative sun exposure and have the potential to become invasive squamous cell carcinomas. The rate of malignant transformation has been variably estimated but is probably no greater than 6% per AK over a 10-year period.1 On a spectrum of malignant transformation, Bowen’s disease is squamous cell carcinoma in situ before the squamous cell carcinoma becomes invasive. In one large prospective trial, the risk of progression of AK to primary SCC (invasive or in situ) was 0.6% at 1 year and 2.6% at 4 years. Approximately 65% of all primary SCCs and 36% of all primary BCCs diagnosed in the study group arose in lesions that had been previously diagnosed clinically as AKs.2

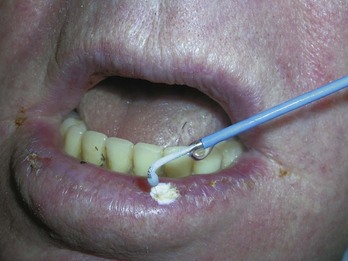

Actinic keratoses are rough scaly spots seen on sun-exposed areas that may be found by touch, as well as close visual inspection. Bowen’s disease appears similar to actinic keratosis, but tends to be larger in size and thicker with a well-demarcated border (Figure 34-2). Actinic cheilitis is equivalent to AK but found on the lips (Figure 34-3).

Treatment of Actinic Keratoses and Actinic Cheilitis

Electrodesiccation and Curettage (Single Cycle for AK)

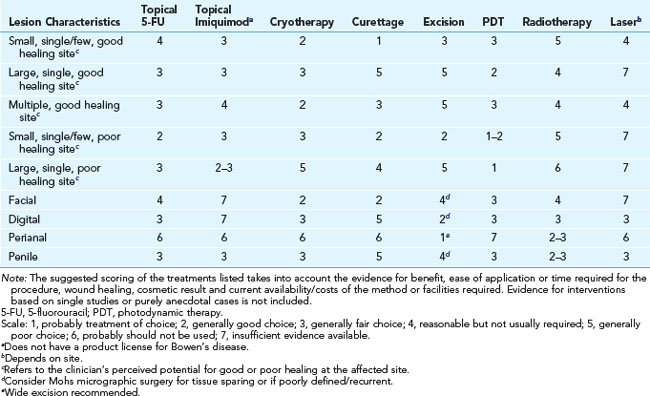

Treatment of Bowen’s Disease

The following is based on the guidelines from Cox et al.4:

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Diagnoses

FIGURE 34-6 Typical nodular BCC on the face of a 53-year-old man. Note the pearly borders and telangiectasias.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Removal

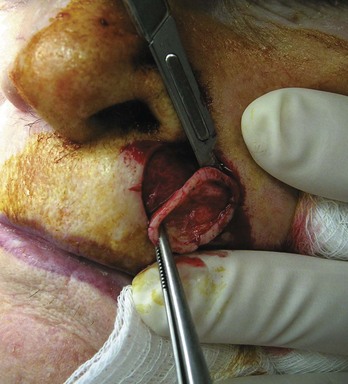

Elliptical Excision (Fusiform) (Figure 34-9)

Electrodesiccation and Curettage

Mohs Micrographic Surgery (Figure 34-13)

TABLE 34-2 Cure Rates for Different Skin Cancer Treatment Modalities

|

|

Five-Year Cure Rate (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

BCC |

SCC |

| Surgical excision | 89.9 | 91.9 |

| Cryotherapy | 92.5 | NA |

| Electrodesiccation and curettage | 92.3 | 96.3 |

| Radiotherapy | 91.3 | 90.0 |

| Mohs surgery | 99.0 | 96.9 |

NA, not applicable.

Source: Data from Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315–328, and J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976–990; and Vidimos A, Ammirati C, Poblete-Lopez C. Dermatologic Surgery. London: Saunders; 2008, Table 16-1.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Diagnoses

Treatment

Special Considerations/Billing

Keratoacanthoma

Diagnosis

Melanoma

Diagnosis

FIGURE 34-18 Superficial spreading melanoma with all features of ABCDE.

(Courtesy of Skin Cancer Foundation, New York, NY.)

The four major categories of melanomas are as follows:

FIGURE 34-20 Superficial spreading melanoma in its radial growth phase on the back of the patient above (0.35 mm in depth).

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

FIGURE 34-22 Lentigo maligna melanoma on the face.

(Courtesy of Skin Cancer Foundation, New York, NY.)

FIGURE 34-23 Acral lentiginous melanoma on the heel of a young woman.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

FIGURE 34-24 Subungual melanoma that has spread to the proximal nail fold producing a positive Hutchinson sign.

(Courtesy of Ryan O’Quinn, MD.)

Less common types of melanomas include the following:

FIGURE 34-25 Amelanotic melanoma arising on the scalp.

(Courtesy of the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, Division of Dermatology, San Antonio, TX.)

Diagnosis starts with history (change) and physical exam (ABCDE).

Treatment

Definitive treatment is based on Breslow depth.

|

Tumor Thickness (Breslow) |

Excision Margin (cm) |

Sentinel Node Biopsy Suggested |

|---|---|---|

| In situ | 0.5 | No |

| <1.0 mm | 1 | No |

| 1.0–2.0 mm | 1 | Yes |

| >2.0 mm | 2 | Yes |

a These recommendations are based on both prospective, randomized studies and international consensus conferences.16,17 Limited data suggest that margin has an effect on local or regional recurrence, but there are no data to support an impact of margin on survival.16,17

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas (Including Mycosis Fungoides)

Biopsy

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Diagnosis

Coding and Billing Pearls

Resources

1. Anwar J, Wrone DA, Kimyai-Asadi A, Alam M. The development of actinic keratosis into invasive squamous cell carcinoma: evidence and evolving classification schemes. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:189-196.

2. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

3. Thai KE, Fergin P, Freeman M, et al. A prospective study of the use of cryosurgery for the treatment of actinic keratoses. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:687-692.

4. Cox NH, Eedy DJ, Morton CA. Guidelines for management of Bowen’s disease: 2006 update. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:11-21.

5. Ridky TW. Nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:484-501.

6. Ahmed I, Agarwal S, Ilchyshyn A, et al. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy of common warts: cryo-spray vs. cotton wool bud. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1006-1009.

7. Ricotti C, Bouzari N, Agadi A, Cockerell CJ. Malignant skin neoplasms. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:1241-1264.

8. Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

9. Szeimies RM. Methyl aminolevulinate-photodynamic therapy for basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:89-94.

10. Marcil I, Stern RS. Risk of developing a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1524-1530.

11. Arora A, Attwood J. Common skin cancers and their precursors. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:703-712.

12. Thomas L. Semiological value of ABCDE criteria in the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Dermatology. 1998;197:11-17.

13. Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, Tucker MA. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986–2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

14. Kalkhoran S, Milne O, Zalaudek I, et al. Historical, clinical, and dermoscopic characteristics of thin nodular melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:311-318.

15. Swetter SM, Boldrick JC, Jung SY, et al. Increasing incidence of lentigo maligna melanoma subtypes: northern California and national trends 1990–2000. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:685-691.

16. Garbe C, Hauschild A, Volkenandt M, et al. Evidence and interdisciplinary consensus-based German guidelines: surgical treatment and radiotherapy of melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:61-67.

17. Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:270-283.

18. Snow SN, Gordon EM, Larson PO, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a report on 29 patients treated by Mohs micrographic surgery with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Cancer. 2004;101:28-38.

19. Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

20. Zampetti A, Feliciani C, Massi G, Tulli A. Updated review of the pathogenesis and management of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010;14:51-61.

21. Tai P, Yu E, Assouline A, et al. Management of Merkel cell carcinoma with emphasis on small primary tumors—a case series and review of the current literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:105-110.

22. Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-636.