CHAPTER 170 Diagnosis and Management of Painful Neuromas

Pathophysiology

The amazing capacity of a peripheral nerve to regenerate after injury enables functional recovery in many cases. Unfortunately, this regenerative capability, when it goes awry, can produce a painful scar at the site of injury. Neuromas can affect any nerve: large, small, or microscopic. The key process that contributes to neuroma formation is the regrowth of injured axons into impenetrable scar. A traumatic neuroma is a dense, minimally vascular fibrous mass containing many small nerve fibers connected to a nerve.1 The fibrous connective tissue that makes up the outer layer of the neuroma is continuous with the perineurium of the involved nerve.2 The injured nerve fibers in a traumatic neuroma cause pain by multiple mechanisms. Spontaneous firing of nociceptors sends impulses centrally, leading to neuropathic pain.3 Additionally, nerve fibers in close proximity to each other may stimulate impulse transmission even in the absence of a synapse between them.4 Further stimulation may occur through the abnormal release of chemical pain mediators.5

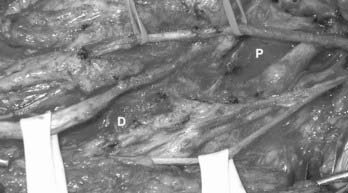

Neuromas may form along nerves after injury, although it is a mystery exactly why they become painful in some cases and not in others. Typically, the traumatic event lacerates the nerve either partially or completely, although essentially any type of injury, such as compression, gunshot wound, or traction, can result in neuroma formation. When the nerve is completely severed (neurotmesis),6 the ends often retract apart. The proximal end sometimes forms a bulbous neuroma, whereas the distal end withers into scar (Fig. 170-1). Because the cut ends are physically separate, the probability of meaningful recovery of axons across the injured segment is vanishingly low.7 Sharp and blunt lacerating injuries often cause this type of neuroma.

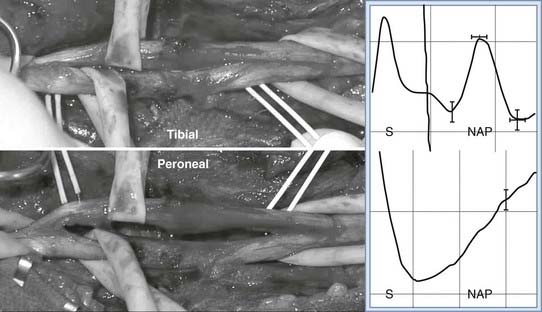

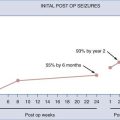

When the axons are severed but the epineurium remains intact (axonotmesis),6 this yields a neuroma-in-continuity. Compression, gunshot wound, and stretch injuries generally cause this type of neuroma. A fusiform neuroma may form along the injured segment (Fig. 170-2). Because the cut ends are together, meaningful recovery of axons across the injured segment often occurs (regenerating neuroma-in-continuity).8 The presence of scar, however, prevents recovery in some cases (nonconducting neuroma-in-continuity). These forms are distinguished most reliably by using intraoperative nerve action potential recordings. Recovering nerve action potentials are seen with a conducting neuroma-in-continuity, but not with a nonconducting neuroma-in-continuity (Fig. 170-3).

Clinical Presentation

Traumatic neuromas are firm, slow-growing, and sometimes palpable nodules that can be associated with pain and paresthesias in the affected area. The hallmark finding for a painful neuroma is an exquisitely sensitive, focal area along the course of a previously injured nerve. Pain is evoked by palpation of the region and may remain local or radiate along the course of the peripheral nerve sensory distribution (Tinel’s sign).4 Patients can also have tenderness and hypersensitivity to normal tactile stimuli in the surrounding regions.2 When the injured nerve is nonfunctional, there is often loss of sensation in the distribution of that nerve.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a neuroma can be made clinically: pain in the region of a scar, altered sensation in the distribution of the affected nerve, and Tinel’s sign. Confirmatory testing may include injection of local anesthetic into the vicinity of the neuroma9 or more proximally along the course of the affected nerve.10 The presence of temporary pain relief helps make the diagnosis of a painful neuroma and additionally may help to identify the exact nerve involved. This may be helpful if multiple candidate nerves are in the vicinity, such as in the inguinal region. Some practitioners use control injections of saline or local anesthetics of differing durations, one long acting and one short acting, in an effort to increase reliability of this diagnostic modality. Such a strategy may help reduce unwanted placebo effects, which can complicate the treatment of any pain disorder.

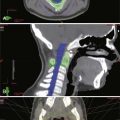

Imaging may be used to identify larger neuromas. Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance neurography may delineate the neuroma clearly in some cases.11 Ultrasonography has been additionally used routinely to image Morton’s neuromas, affecting the plantar digital nerves that form near the metatarsal heads after repetitive compression trauma.12

Perhaps the most reliable way to identify a neuroma is with surgical exploration in the awake patient. Following external neurolysis of the neuroma, when palpation of the neuroma reproduces the patient’s exact pain, little diagnostic uncertainty remains. This strategy is essentially identical, in theory, to the conscious pain mapping procedures used by gynecologists during laparoscopic procedures to identify pelvic pain generators.13

Treatment

When a painful neuroma is diagnosed, a comprehensive, pain management–oriented approach may be helpful. Initial efforts may involve over-the-counter pain medications and protecting the painful area from additional trauma. Anticonvulsant14 and antidepressant15 medications may provide relief for neuropathic pain. Opiates16 may also reduce pain levels. Complementary and alternative therapies such as acupuncture may be useful.17

When these noninvasive efforts are insufficient, a more aggressive strategy may be required. Steroid injections, sometimes coupled with a local anesthetic, may provide temporary and, in some cases, durable pain relief.18 Ablative techniques such as radiofrequency ablation, pulsed radiofrequency ablation, or chemical neurectomy19 may destroy the associated nerve or neuroma, providing the necessary pain relief. There is a paucity of high-quality clinical data supporting the use of these techniques, however.

Open surgery is another option in the treatment of painful neuromas. A major problem in neuroma excision is the recurrence of the neuroma, and prevention of growth of a secondary neuroma is a key part of surgical treatment. In the past, treatment of neuromas involved neuroma excision followed by capping the nerve with many substances, including silicone and surplus epineurium, to prevent new neuroma formation.20 Additionally, chemical treatment of the cut proximal end of the nerve has been used.21 One study reported that oblique transection of peripheral nerves, as opposed to perpendicular transection, greatly reduces the rate of classic neuroma development.22 Additionally, this method of oblique transection was thought to significantly reduce neuropathic pain compared with that following the traditional form of nerve transection.

A different surgical strategy emphasizes placement of the cut end of nerve into an appropriate environment and does not attempt to physically restrain axonal outgrowth.23 Using a primate model of a neuroma, transection of the radial sensory nerve at the wrist, followed by turning the sensory nerves proximally and implanting them into a forearm muscle, effectively prevented classic neuroma formation. Specifically, the sensory nerve showed no signs of regeneration when implanted into the muscle.24 Meyer and colleagues25 produced superficial radial nerve neuromas in a group of baboons and found that neuromas produce spontaneous activity of pain fibers and are sensitive to mechanical stimulation. Thus, muscle reimplantation may also reduce pain caused by mechanohypersensitivity by decreasing the mechanical stimulation encountered by the neuroma.24 In a study by Burchiel and colleagues26 of 18 patients with distal sensory neuromas, reimplantation of nerve endings showed a success rate of 44% and an average drop in visual analog scale–registered pain of 32%. Dellon and Mackinnon27 found that 80% of patients had excellent pain relief after neuroma resection and reimplantation into muscle. They suggested that the nerve must be directed into muscle without tension in a distal-to-proximal direction to accommodate the minimal amount of nerve regeneration that will inevitably occur and should be implanted in muscles with minimal excursion to keep the implanted nerve in place. Additionally, if the nerve is implanted near the deep surface of the muscle, regeneration into the overlying skin is prevented, thus reducing mechanical stimulation of the nerve.28

For superficial neuromas along named peripheral nerves, an attempt is made in the mildly sedated patient to subject the nerve to an external neurolysis and definitively identify the nerve. Palpation of the suspected neuroma should reproduce the patient’s pain (Fig. 170-4). Once located, the nerve is sectioned proximal to the neuroma, and the neuroma is removed. When the nerve arises from muscle proximally, such as the plantar digital nerves, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, or the abdominal nerves such as the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal, sectioning the nerve under tension allows it to retract into the muscle. Once in muscle, the likelihood of neuroma recurrence is reduced. If the nerve does not arise from nearby muscle, the nerve may be transposed to a nearby muscle, implanted through a small incision in the muscle belly, and sutured into place (Fig. 170-5).

The practicing neurosurgeon may encounter cases in which neuroma excision surgery is inappropriate. For example, patients who have already undergone one or more failed neuroma excision surgeries, in our experience, do not experience pain relief with additional neurectomy surgery. We can only speculate as to the reason at this point, but centralization of the pain generators and psychological factors may play a role. Postamputation neuromas of large, mixed nerves such as the sciatic nerve may be especially problematic for the surgeon. Wound healing in these regions may be fraught with difficulties. In most cases, unless there is a clear-cut structural abnormality in a stump, such as a sharp end of bone cutting into the nerve, local excision surgery should probably be avoided.29

When surgical excision of neuromas is thought to be inappropriate and patients have failed less invasive measures, interventional pain management techniques may be used. Specifically, neurostimulation can be quite helpful, depending on the distribution of pain.30 Neuroma pain in the extremities can generally be treated with spinal cord stimulation. Spinal nerve root stimulation, which targets pain-relieving stimulation paresthesias into the distribution of single or multiple nerve roots, may provide relief to patients with pain in the hands, feet, inguinal regions, pelvic regions, and intercostal distributions.31 These areas are often unreachable with spinal cord stimulation. Small regions of neuroma pain, inaccessible to spinal nerve root or spinal cord stimulation, may be targeted effectively with subcutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation32 in which the electrodes are placed under the skin at the site of pain (Fig. 170-6).

Almeida ODJr, Val-Gallas JM. Conscious pain mapping. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4:587-590.

Battista AF, Cravioto HM, Budzilovich GN. Painful neuroma: changes produced in peripheral nerve after fascicle ligation. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:589-600.

Boutin RD, Pathria MN, Resnick D. Disorders in the stumps of amputee patients: MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:497-501.

Braverman DL, Ericken JJ, Shah RV, Franklin DJ. Interventions in chronic pain management. 3. New frontiers in pain management: complementary techniques. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(supp1):S45-S49.

Burchiel KJ, Johans TJ, Ochoa J. The surgical treatment of painful traumatic neuromas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:714-719.

Defalque RJ. Painful trigger points in surgical scars. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:518-520.

Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Treatment of the painful neuroma by neuroma resection and muscle implantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:427-436.

Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Pestronk A. Implantation of sensory nerve into muscle: preliminary clinical and experimental observation on neuroma formation. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;12:30-40.

Foltan R, Klima K, Spackova J, Sedy J. Mechanism of traumatic neuroma development. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:572-576.

Haque R, Winfree CJ. Spinal nerve root stimulation. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21:1-7.

Hassouna H, Singh D, Taylor H, Johnson S. Ultrasound guided steroid injection in the treatment of interdigital neuralgia. Acta Orthopaed Belg. 2007;73:224-229.

Kline DG. Timing for exploration of nerve lesions and evaluation of the neuroma-in-continuity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:42-49.

Lee MJ, Kim S, Huh YM, et al. Morton neuroma: evaluated with ultrasonography and MR imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:148-155.

Mackinnon SE. Evaluation and treatment of the painful neuroma. Tech Hand Upper Extrem Surg. 1997;1:195-212.

Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Results of treatment of recurrent dorsoradial wrist neuromas. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;19:54-61.

Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Algorithm for management of painful neuroma. Contemp Orthop. 1986;13:15-27.

Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL, Hudson AR, Hunter DA. Alteration of neuroma by manipulation of neural microenvironment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:345-352.

Marcol W, Kotulska K, Larysz-Brysz M, et al. Prevention of painful neuromas by oblique transection of peripheral nerves. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:285-289.

Meyer RA, Srinivasan R, Campbell JN, et al. Neural activity originating from a neuroma in the baboon. Brain Res. 1985;325:255-260.

Mozena JD, Clifford JT. Efficacy of chemical neurolysis for the treatment of interdigital nerve compression of the foot: a retrospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2007;97:203-206.

Przewlocki R, Przewlocka B. Opioids in neuropathic pain. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3013-3025.

Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005454.

Scadding JW. Development of ongoing activity, mechanosensitivity, and adrenaline sensitivity in severed peripheral nerve axons. Exp Neurol. 1981;73:345-364.

Seddon HJ. Three types of nerve injury. Brain. 1943;66:236-288.

Seltzer Z, Devor M. Ephaptic transmission in chronically damaged peripheral nerves. Neurology. 1974;29:1061-1064.

Stewart JD. Pathologic processes producing focal peripheral neuropathies. In: Stewart JD, editor. Focal Peripheral Neuropathies. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:11-35.

Stinson LW, Roderer GT, Cross NE, Davis BE. Peripheral subcutaneous electrostimulation for control of intractable post-operative inguinal pain: a case report series. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:99-104.

Stuart RM, Winfree CJ. Neurostimulation techniques for painful peripheral nerve disorders. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2009;20:111-120.

Swanson AB, Boeve NR, Lumsden RM. The prevention and treatment of amputation neuromata by silicone capping. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2:70-78.

Wall PD, Gutnick M. Properties of afferent nerve impulses originating from a neuroma. Nature. 1974;248:740-742.

Wellons JC, Gorecki JP, Friedman AH. Stump, phantom, and avulsion pain. In: Burchiel KJ, editor. Surgical Management of Pain. New York: Thieme; 2002:422-442.

Wiffen P, Collins S, McQuay H, et al. Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD001133.

1 Scadding JW. Development of ongoing activity, mechanosensitivity, and adrenaline sensitivity in severed peripheral nerve axons. Exp Neurol. 1981;73:345-364.

2 Foltan R, Klima K, Spackova J, Sedy J. Mechanism of traumatic neuroma development. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:572-576.

3 Wall PD, Gutnick M. Properties of afferent nerve impulses originating from a neuroma. Nature. 1974;248:740-742.

4 Seltzer Z, Devor M. Ephaptic transmission in chronically damaged peripheral nerves. Neurology. 1974;29:1061-1064.

5 Mackinnon SE. Evaluation and treatment of the painful neuroma. Tech Hand Upper Extrem Surg. 1997;1:195-212.

6 Seddon HJ. Three types of nerve injury. Brain. 1943;66:236-288.

7 Stewart JD. Pathologic processes producing focal peripheral neuropathies. In: Stewart JD, editor. Focal Peripheral Neuropathies. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:11-35.

8 Kline DG. Timing for exploration of nerve lesions and evaluation of the neuroma-in-continuity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:42-49.

9 Defalque RJ. Painful trigger points in surgical scars. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:518-520.

10 Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Results of treatment of recurrent dorsoradial wrist neuromas. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;19:54-61.

11 Boutin RD, Pathria MN, Resnick D. Disorders in the stumps of amputee patients: MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:497-501.

12 Lee MJ, Kim S, Huh YM, et al. Morton neuroma: evaluated with ultrasonography and MR imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:148-155.

13 Almeida ODJr, Val-Gallas JM. Conscious pain mapping. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4:587-590.

14 Wiffen P, Collins S, McQuay H, et al. Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD001133.

15 Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005454.

16 Przewlocki R, Przewlocka B. Opioids in neuropathic pain. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3013-3025.

17 Braverman DL, Ericken JJ, Shah RV, Franklin DJ. Interventions in chronic pain management. 3. New frontiers in pain management: complementary techniques. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(supp1):S45-S49.

18 Hassouna H, Singh D, Taylor H, Johnson S. Ultrasound guided steroid injection in the treatment of interdigital neuralgia. Acta Orthopaed Belg. 2007;73:224-229.

19 Mozena JD, Clifford JT. Efficacy of chemical neurolysis for the treatment of interdigital nerve compression of the foot: a retrospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2007;97:203-206.

20 Swanson AB, Boeve NR, Lumsden RM. The prevention and treatment of amputation neuromata by silicone capping. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2:70-78.

21 Battista AF, Cravioto HM, Budzilovich GN. Painful neuroma: changes produced in peripheral nerve after fascicle ligation. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:589-600.

22 Marcol W, Kotulska K, Larysz-Brysz, et al. Prevention of painful neuromas by oblique transection of peripheral nerves. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:285-289.

23 Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL, Hudson AR, Hunter DA. Alteration of neuroma by manipulation of neural microenvironment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:345-352.

24 Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Algorithm for management of painful neuroma. Contemp Orthop. 1986;13:15-27.

25 Meyer RA, Srinivasan R, Campbell JN, et al. Neural activity originating from a neuroma in the baboon. Brain Res. 1985;325:255-260.

26 Burchiel KJ, Johans TJ, Ochoa J. The surgical treatment of painful traumatic neuromas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:714-719.

27 Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Pestronk A. Implantation of sensory nerve into muscle: preliminary clinical and experimental observation on neuroma formation. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;12:30-40.

28 Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Treatment of the painful neuroma by neuroma resection and muscle implantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:427-436.

29 Wellons JC, Gorecki JP, Friedman AH. Stump, phantom, and avulsion pain. In: Burchiel KJ, editor. Surgical Management of Pain. New York: Thieme; 2002:422-442.

30 Stuart RM, Winfree CJ. Neurostimulation techniques for painful peripheral nerve disorders. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2009;20:111-120.

31 Haque R, Winfree CJ. Spinal nerve root stimulation. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21:1-7.

32 Stinson LW, Roderer GT, Cross NE, Davis BE. Peripheral subcutaneous electrostimulation for control of intractable post-operative inguinal pain: a case report series. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:99-104.