Chapter 50 Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State

3 What is the pathogenesis of DKA?

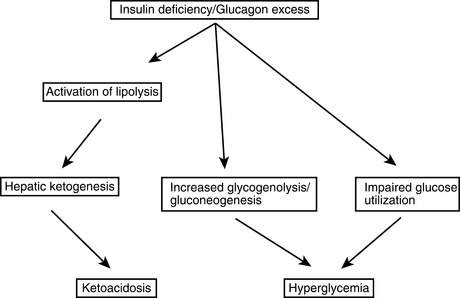

DKA starts withabsolute insulin deficiencybecause of a broken or clogged insulin pump, missed injections, or progression of an unknown illness to overt insulin deficiency or withrelative insulin deficiencyfrom a rise in tissue insulin requirements from infection, trauma, or other stresses. Glucose production from the liver increases, and glucose clearance into peripheral tissues is impaired, causing the blood glucose level to rise. Stress-related increases in counterregulatory hormones exacerbate these effects. As the renal glucose threshold is passed, an osmotic diuresis occurs causing urinary losses of water and electrolytes. The ensuing dehydration further increases the level of catecholamines. Also, because glucagon and insulin levels are normally inversely related, the insulin deficiency causes hyperglucagonemia. The increased catecholamines and glucagon and the insulin deficiency promote excess release of fatty acids from the adipose tissue that further impairs insulin-mediated glucose uptake into peripheral tissues. The capacity of the liver for β-oxidation of the fatty acids is exceeded, resulting in ketone production. This ketonemia and the resulting acidosis often cause nausea and vomiting; the patient’s polydipsia therefore stops, worsening the dehydration. The patient is now in DKA with this whole process occurring over a 12- to 48-hour period. This sequence of events is depicted inFigure 50-1.

9 How does the hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) differ from DKA?

Occurs most often in the elderly and those with known type 2 diabetes

Occurs most often in the elderly and those with known type 2 diabetes

Very high blood glucose levels of 600 mg/dL or greater

Very high blood glucose levels of 600 mg/dL or greater

Markedly elevated serum osmolarity of 320 mOsm/kg or greater

Markedly elevated serum osmolarity of 320 mOsm/kg or greater

Frequent occurrence of altered mental state or coma

Frequent occurrence of altered mental state or coma

More serious hypotension and overt dehydration including substantially larger electrolyte losses than DKA

More serious hypotension and overt dehydration including substantially larger electrolyte losses than DKA

High mortality rate that averages 15% versus less than 2% in uncomplicated DKA

High mortality rate that averages 15% versus less than 2% in uncomplicated DKA

19 How is hyperosmolarity calculated in HHS?

Mortality also rises substantially with levels above 350 mOsm/L.

29 What are the goals of therapy in HHS?

33 What complications can occur in DKA and HHS?

Key Points Goals of therapy for hyperglycemic crises

1. Restore hemodynamic stability, and replete whole-body electrolyte stores with fluid replacement.

2. Recover blood glucose control with insulin therapy.

3. Identify and start therapy for any precipitating illness.

4. Prevent hypophosphatemia and hypoglycemia.

5. Closely monitor for the complications that can occur during therapy.

1 Arora S., Henderson S.O., Long T., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care testing for diabetic ketoacidosis at emergency-department triage: β-hydroxybutyrate versus the urine dipstick. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:852–854.

2 Canarie M.F., Bogue C.W., Banasiak K.J., et al. Decompensated hyperglycemic hyperosmolarity without significant ketoacidosis in the adolescent and young adult population. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20:1115–1124.

3 Ennis E.D., Kreisberg R.A. Diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome. In: D LeRoith, SL Taylor, JM Olesfsky. Diabetes Mellitus: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:627–642.

4 Kitabchi A.E., Murphy M.B., Spencer J., et al. Is a priming dose of insulin necessary in a low-dose insulin protocol for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis? Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2081–2085.

5 Kitabchi A.E., Nyenwe A.E. Hyperglycemic crisis in diabetes mellitus: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35:225–251.

6 Kitabchi A.E., Umpierrez G.E., Fisher J.N., et al. Thirty years of personal experience in hyperglycemic crisis: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1541–1552.

7 Kitabchi A.E., Umpierrez G.E., Murphy M.B., et al. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2739–2748.

8 Krane E.J., Rockoff M.A., Wallman J.K., et al. Subclinical brain swelling in children during treatment of diabetes ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1147–1151.

9 Morris L.R., Murphy M.B., Kitabchi A.E., et al. Bicarbonate therapy in severe diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:836–840.

10 Nugent B.W. Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:629–648.

11 Orlowski J.P., Cramer C.L., Fiallos M.R. Diabetic ketoacidosis in the pediatric ICU. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:577–587.

12 Parker J.A., Conway D.L. Diabetic ketoacidosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:533–543.

13 Rosenbloom A.L. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: an emerging pediatric problem. J Pediatr. 2010;156:180–184.

14 Savage M.W., Dhatariya K.K., Kilvert A., et al. Joint British Diabetes Societies guideline for the management of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:508–511.

15 Umpierrez G. Narrative review: ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:350–357.

16 Usher-Smith J.A., Thompson M.J., Sharp S.J., et al. Factors associated with the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of diabetes in children and young adults: a systematic review. BMJ. 2011;343:d4092.

17 Westphal S.A. The occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis in non-insulin-dependent diabetes and newly diagnosed diabetic adults. Am J Med. 1996;101:19–24.

18 Wilson J.F. In the clinic. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:ITC1–ITC16.

19 Wolfsdorf J., Craig M.E., Daneman D., et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10 Suppl 12:118–133.

20 Wyckoff J., Abrahamson M.J. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. In: CR Kahn, GC Weir, GL King, et al. Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:887–899.