44 Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is the most common of the endocrine disorders. It is a chronic condition, characterised by hyperglycaemia and due to impaired insulin secretion with or without insulin resistance. Diabetes mellitus may be classified according to aetiology, by far the most common types being type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Box 44.1). More than 2.6 million people in the UK have diabetes, and by the year 2025, this number is estimated to rise to 4 million.

Box 44.1 Aetiological classification of diabetes mellitus

Type 1 (β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency)

Type 2 diabetes is more common above the age of 40, with a peak age of onset in developed countries between 60 and 70 years, although it is being increasingly seen in younger people and even children. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes varies widely in different populations, being six times more common in those of South Asian origin compared with those of Northern European origin. It is caused by a relative insulin deficiency and insulin resistance. Symptoms are generally slower in onset and less marked than those of type 1. Type 2 diabetes may be an incidental finding, particularly when patients present with complications associated with the disease, for example, heart disease. Type 2 disease often progresses to the extent whereby extrinsic insulin is required to maintain blood glucose levels. The differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes are highlighted in Table 44.1. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish clinically between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The important thing to be aware of is that it is predominantly the degree of metabolic abnormality that is the key determinant of the form of treatment.

Table 44.1 Differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes

| Type 1 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes |

|---|---|

| β-cell destruction | No β-cell destruction |

| Islet cell antibodies present | No islet cell antibodies present |

| Strong genetic link | Very strong genetic link |

| Age of onset usually below 30 | Age of onset usually above 40 |

| Faster onset of symptoms | Slower onset of symptoms |

| Insulin must be administered | Diet control and oral hypoglycaemic agents often sufficient control |

| Patients usually not overweight | Patients usually overweight |

| Extreme hyperglycaemia causes diabetic ketoacidosis | Extreme hyperglycaemia causes hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state |

Pathophysiology

Type 2 diabetes is also associated with the metabolic syndrome (or syndrome X), although the real relevance of this ‘syndrome’ continues to be debated in the literature (Khan et al., 2005). The metabolic syndrome is a group of risk factors commonly found in those with type 2 diabetes, including insulin resistance, glucose intolerance (type 2 diabetes or IGT), hyperinsulinaemia, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, central obesity, atherosclerosis and increased levels of procoagulant factors, for example, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and fibrinogen.

Diagnosis

In June 2000, the UK formally adopted the World Health Organization criteria for diagnosing diabetes mellitus that was initially published in 1999. It has since been updated and the diagnostic criteria have been reiterated (World Health Organization, 2006).

Diabetic emergencies

Hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia can occur both with insulin treatment and in those taking some oral agents, especially the longer-acting sulphonylureas, for example, chlorpropamide and glibenclamide. Definitions of hypoglycaemia vary, and in particular, there is no WHO definition. However, symptoms caused by the release of counter-regulatory hormones predominantly adrenaline (epinephrine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and glucagon tend to occur when the venous serum glucose drops below 3.0 mmol/L in healthy individuals. These symptoms described in Box 44.2 are a normal physiological response to hypoglycaemia and should alert the person to consume carbohydrates. Individuals may not respond appropriately to hypoglycaemia of this degree for several reasons, termed hypoglycaemia unawareness. First, the relevance of the symptoms has not been explained to them. This is an educational failing. It is imperative, therefore, that people with diabetes who are prescribed medication which is known to cause hypoglycaemia should be educated about the autonomic symptoms so that they may take action to avoid further decline of serum glucose. Second, the symptoms simply may not occur because of autonomic neuropathy. One of the commonest complications of diabetes is neuropathy, and when this includes the autonomic nervous system, there are no reliable symptoms to warn the individual that they are hypoglycaemic. A similar situation may occur as a consequence of drugs which suppress autonomic symptoms, such as β-blockers. Third, the patient may have recurrent hypoglycaemia. In those individuals who suffer frequent hypoglycaemic episodes, the autonomic symptoms may cease to occur. There is some evidence that the symptoms can be regained if, for a period of a few weeks, the serum glucose level can be maintained out of the hypoglycaemic range. Finally, the individual may be hypoglycaemia unaware because of alcohol intoxication.

Causes of hypoglycaemia

The most common causes of hypoglycaemia are either a decrease in carbohydrate consumption, excess carbohydrate utilisation from unexpected exercise or increase in circulating insulin (Table 44.2).

| Cause | Comment |

|---|---|

| Missed meals or delays in eating | Reduced carbohydrate intake, therefore reduction in glucose levels |

| Not eating the usual amount of carbohydrates | Reduced carbohydrate intake, therefore reduction in glucose levels |

| Increased doses of insulin | Increased uptake of glucose into cells and increased storage of glucose as glycogen |

| Increased doses of oral insulin secretagogues | Increased levels of insulin therefore increased uptake of glucose into cells and increased storage of glucose as glycogen |

| Introduction of other blood glucose-lowering agents to oral insulin secretagogues | Enhanced hypoglycaemic effects |

| Increase in exercise | Increased uptake of glucose into cells |

| Excessive alcohol consumption | Impaired gluconeogenesis |

| Liver disease | Impaired gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis |

Long-term diabetic complications

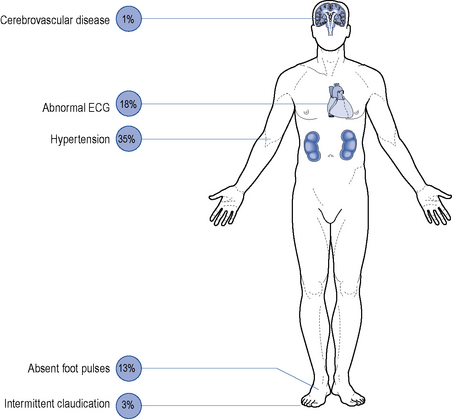

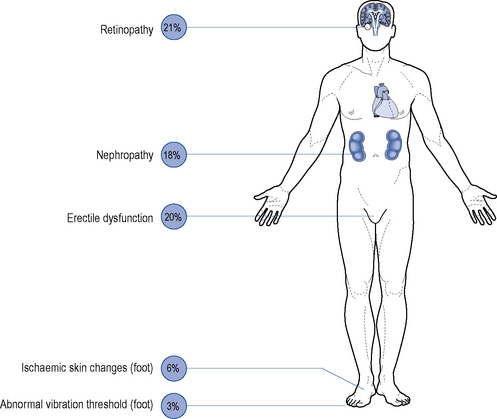

Although all long-term complications may occur in each type of diabetes, the spectrum of incidence is different. Many patients with type 2 diabetes have had their disease a long time before the diagnosis, by which time many have developed diabetic complications (Figs. 44.1 and 44.2). However, diabetic complications can be limited and sometimes prevented altogether if good management occurs from an early stage. Hyperglycaemia and hypertension are the two major modifiable risk factors that influence the development of diabetic complications.

Macrovascular disease

Microvascular disease

Microvascular complications include retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy.

Peripheral neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy is the progressive loss of peripheral nerve fibres resulting in nerve dysfunction. Diabetic neuropathies can lead to a wide variety of sensory, motor and autonomic symptoms. The most common is the symmetrical distal sensory type, which is particularly evident in the feet and may slowly progress to a complete loss of feeling. It is most prevalent in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes but may be found with any type of diabetes, at any age beyond childhood. Painful diabetic neuropathy is another manifestation of sensory neuropathy; it can be extremely disabling and may cause considerable morbidity. Guidance on the treatment of painful neuropathy is available (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010). Diabetic proximal motor neuropathy is rapid in onset and involves weakness and wasting, principally of the thigh muscles. Muscle pain is common and may require opiate analgesia. Distal motor neuropathy can lead to symptoms of impaired fine co-ordination of the hands and/or foot slapping.

Treatment

Diet

Dietary control is the mainstay of treatment for type 2 diabetes and plays an integral part in the management of type 1. Dietary recommendations have undergone extensive review in recent years and considerable changes have been made. Generally speaking, healthy eating advice for people with diabetes is the same as for the general population. Some of the general dietary advice that patients should be given is shown in Box 44.3.

Box 44.3 General dietary advice for people with diabetes

Obesity management in type 2 diabetes

Obesity management is a very important issue in type 2 diabetes owing to the insulin resistance which occurs as a consequence of excess adipose tissue. Whilst any loss of weight in those who are overweight or obese is of benefit in diabetes in that it is associated with an improvement in dyslipidaemia, hypertension and glycaemic control, bariatric surgery can lead to profound improvements. Recent studies have shown that laparoscopic banding can induce remission of type 2 diabetes in 48% of individuals and Roux-en-y bypass procedures can induce remission in 84%. More importantly, bariatric surgery is associated with a 92% relative risk reduction in diabetes-specific mortality and consequently should be offered to those with diabetes who have a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006). For those with a BMI of 28 kg/m2 or greater, it is recommended that the pancreatic and gastric lipase inhibitor, orlistat, be considered as the modest weight reduction which can be achieved with this agent yields benefits in diabetes control.

Insulin therapy in type 1 diabetes

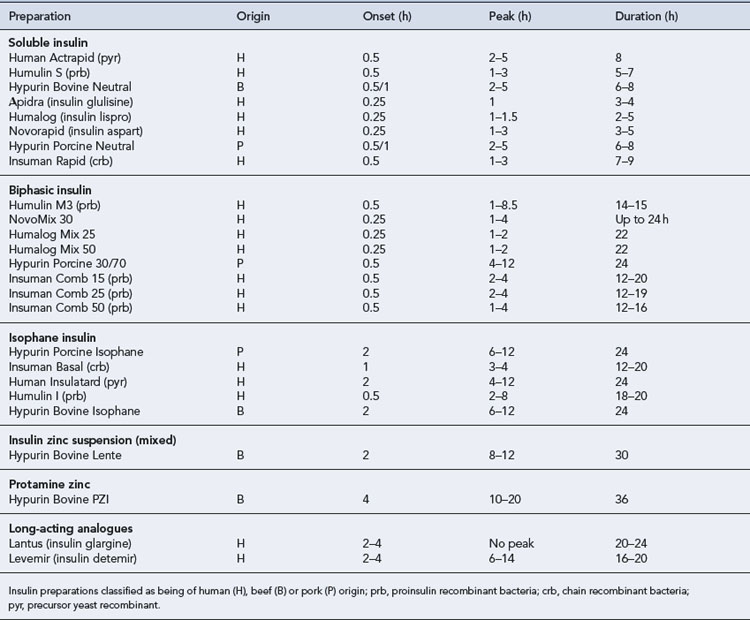

All patients with type 1 diabetes require treatment with insulin in order to survive. Exogenous insulin is used to mimic the normal physiological pattern of insulin secretion as closely as possible for each individual patient. However, a balance is required between tight glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia risk. If the risk of hypoglycaemia is high, then it may be necessary to aim for less tight glycaemic control. There is a wide variety of insulin preparations available which differ in species of origin, onset of action, time to peak effect and duration of action (Table 44.3).

Insulin regimens

Mealtime plus basal regimens

The best control for type 1 diabetes may be attained using a mealtime plus basal regimen, also referred to as a basal-bolus regimen. This mimics normal physiological insulin release more closely than other regimens. A mealtime plus basal regimen requires mealtime injections of insulin with a fast-acting preparation, preferably with an analogue, plus one or two injections of a basal (intermediate- or long-acting) insulin. This may require up to five injections a day. As a general rule, with this regimen, the soluble insulin injections given before each meal usually comprise 40–60% of the total daily dosage. Some individuals may benefit from exogenous insulin delivery via a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion administered via a pump worn on their person. The pump can be programmed to give a different basal rate of infusion at different times of day, and boluses are then provided by the pump at mealtimes. There are specific indications for pump therapy (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008).

These regimens offer the most flexibility of dosing and eating habits, and often better blood glucose control. A number of patients have been taught to count mealtime carbohydrates and calculate their own insulin dose on the basis of the preprandial blood glucose concentration, which allows greater scope for ‘normal eating’. An example is the DAFNE (dose adjusted for normal eating) programme (DAFNE Study Group, 2002), in which patients are required to attend structured, group education on five consecutive days.

Management of type 2 diabetes

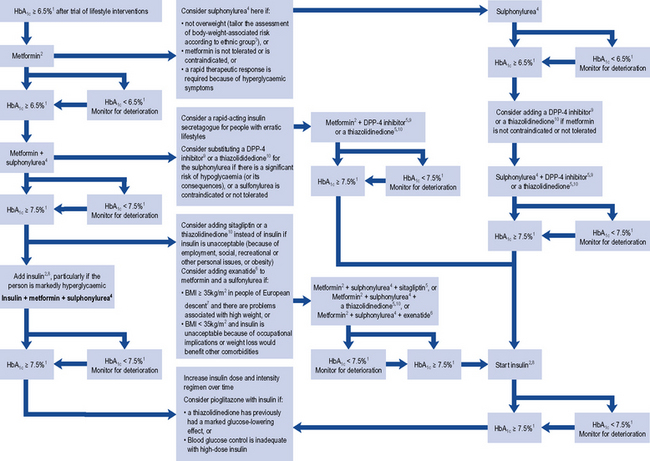

The factors used to select a particular treatment include the patient’s clinical characteristics, such as their degree of hyperglycaemia, weight and renal function (Fig. 44.3). In acutely ill people with significant hyperglycaemia, insulin therapy may well be required, albeit transiently because acute illness leads to an increase in stress hormones, all of which are anti-insulin.

Fig. 44.3 Algorithm for the treatment of glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. (1) or individually agreed target, (2) with active dose titration (3) see the NICE clinical guideline on obesity (www.nice.org.uk/CG43), (4) offer once-daily sulphonylurea if adherence is a problem, (5) only continue DPP-4 inhibitor or thiazolidinedione if reduction in HbA1c of at least 0.5 percentage points in 6 months, (6) only continue exenatide if reduction in HbA1c of at least 1 percentage point and weight loss of at least 3% of initial body weight in 6 months, (7) with adjustment for other ethnic groups, (8) continue with metformin and sulfylurea (and acarbose if used), but only continue other drugs that are licensed for use with insulin. Review the use of sulphonylurea if hypoglycaemia occurs, (9) DPP-4 inhibitor refers to saxagliptin, sitagliptin or vidagliptin, (10) thiazolidinedione refers to ploglitazone.

Sulphonylureas

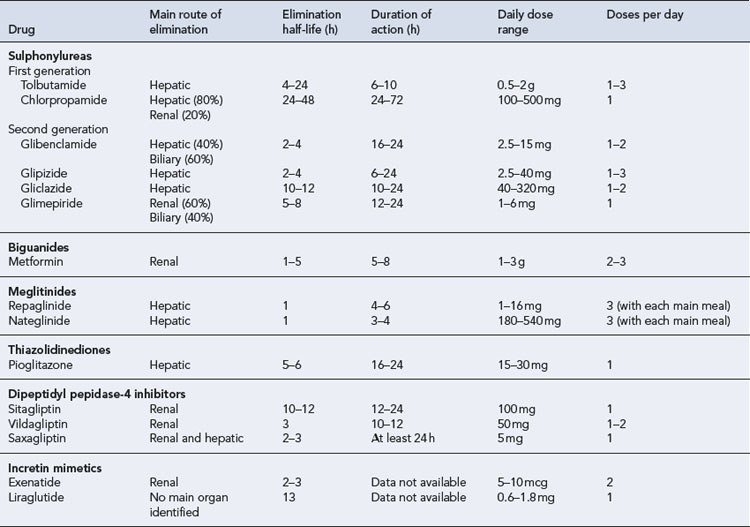

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic parameters of oral hypoglycaemic agents are shown in Table 44.4. Chlorpropamide is the slowest and longest acting agent, but it is now very rarely used. Although glibenclamide has been shown to have a short elimination half-life, it has a prolonged biological effect, which may be explained by slower distribution and the existence of a deep compartment, possibly the islet cells. All sulphonylureas are metabolised by the liver to some degree and some may have active metabolites.

Adverse effects

The frequency of adverse effects from sulphonylureas is low. They are usually mild and reversible on drug withdrawal (Table 44.5). The most common adverse effect is hypoglycaemia, which may be profound and long lasting. Hypoglycaemia due to sulphonylureas is often misdiagnosed, particularly in the elderly. The major risk factors for the development of hypoglycaemia include use of a long-acting agent, increasing age, renal or hepatic dysfunction and inadequate carbohydrate intake. The major side effect is, however, weight gain.

| Adverse effect | Comments |

|---|---|

| Gastro-intestinal | Affects approximately 2% |

| Most commonly nausea and vomiting | |

| Dose related | |

| Advise patient to take with or after food | |

| Dermatological | Affects 1–3% |

| Usually occur within the first 2–6 weeks | |

| Most commonly: generalised photosensitivity, pruritus, maculopapular rash | |

| May require discontinuation of drug | |

| Cross-sensitivity between sulphonylureas is common | |

| Rare cases of severe allergic reactions, for example, erythema multiforme Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

| Haematological | Rare cases of fatal agranulocytosis or pancytopenia |

| Other haematological effects usually reversible on discontinuing drug | |

| Some reports of reversible haemolytic anaemia | |

| Hepatic | Mild, reversible elevation of liver function tests |

| Cholestatic jaundice | |

| Usually a hypersensitivity reaction associated with fever, rash and eosinophilia | |

| Cardiovascular | Possible excess of cardiovascular mortality in patients treated with tolbutamide (not proven) |

| Hypothyroidism | Association not proven |

| May be rare cases | |

| Alcohol flush | Rarely seen with sulphonylureas other than chlorpropamide |

| Change to another agent | |

| Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) | Chlorpropamide and, to a lesser extent, tolbutamide enhance the effect of ADH on the kidney |

| Results in hyponatraemia | |

| Risk factors are increasing age, congestive cardiac failure and diuretic therapy | |

| Hypoglycaemia | The most common adverse effect and may be severe and prolonged |

| Highest incidence with chlorpropamide and glibenclamide | |

| All sulphonylureas and meglitinides have been implicated | |

| Risk factors include increasing age, impaired renal or hepatic function, reduced food intake, weight loss | |

| Decrease dose, change to a shorter-acting agent or discontinue sulphonylurea therapy |

Meglitinides

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic properties of the meglitinides confer a rapid onset and a short duration of action. The individual parameters are shown in Table 44.4. The meglitinides are extensively metabolised in the liver, repaglinide by oxidative biotransformation and direct conjugation with glucuronic acid. The cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 have been shown in vitro to be involved its metabolism. Nateglinide is metabolised predominantly by cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2C9 and to a lesser extent by CYP3A4. Repaglinide has no active metabolites, but nateglinide has partially active metabolites, one-third to one-sixth the potency of the parent compound. The meglitinides should be taken immediately before main meals, although the time can vary up to 30 min before a meal. The pharmacokinetic profile of meglitinides offers some advantages in patients with poor renal function or irregular eating habits.

Thiazolidinediones

Research into the action of the thiazolidinediones, also known as glitazones, has led to greater understanding of the development of type 2 diabetes. Only one glitazone, pioglitazone, is currently available following the removal of rosiglitazone from the UK market in 2010. Pioglitazone has been shown to have a significant benefit on macrovascular morbidity and mortality, demonstrating the benefit of a glucose-lowering agent on macrovascular disease (Dormandy et al., 2005).

Pharmacokinetics

Pioglitazone is metabolised extensively in the liver to both active and inactive metabolites (see Table 44.4).

Role of thiazolidinediones

Glitazones should be used as third-line therapy after life style modification and the use of metformin or a sulphonylurea as monotherapy. However, if glycaemic control remains poor, pioglitazone can be used either with metformin if treatment with a sulphonylurea is unsuitable, with a sulphonylurea if treatment with metformin is unsuitable, or with metformin and a sulphonylurea if insulin is unsuitable (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009). Treatment should only be continued if, after 6 months of treatment, the HbA1c has reduced by 0.5% of its starting value.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

Pharmacokinetics

DPP-4 inhibitors are predominantly renally excreted. However, there is also a degree of hepatic metabolism involved in the elimination process, which varies with each drug. Sitagliptin is mainly excreted as unchanged drug in the urine, with a small metabolic contribution from the liver via the cytochrome P450 system. The kidney is thought to be mainly responsible for metabolic hydrolysis of vildagliptin to an inactive compound. Although saxagliptin is mainly eliminated renally, some hepatic biotransformation does occur via the cytochrome P450 system (CYP3A4/5), which results in a metabolite with half the potency of the parent compound. The pharmacokinetic parameters of the DPP-4 inhibitors are detailed in Table 44.4.

Incretin mimetics

Pharmacokinetics

Incretin mimetics have a longer duration of action than endogenous GLP-1. Exenatide is eliminated primarily by renal clearance. However, the specific organ responsible for liraglutide elimination has not been identified. Table 44.4 details additional pharmacokinetic parameters of the incretin mimetics.

Insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes

The younger age of onset of type 2 diabetes and tighter glycaemic targets mean that the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes progress to insulin therapy, since recent evidence confirms that long-term glycaemic improvement reduces the risk of both microvascular (Holman et al., 2008) and macrovascular (Turnbull et al., 2009) complications.

It is currently common practice to introduce insulin to an oral medication schedule, although if hypoglycaemia becomes a problem, then the oral medications may be reduced or stopped. A number of different insulin regimens for use in patients with type 2 diabetes are available, the most common of which include once-daily basal insulin, twice-daily biphasic (pre-mixed) insulin, or prandial insulin, using a rapid/short-acting insulin with meals. Until recently, there have not been any trial data to determine which insulin regimen is most effective in controlling blood glucose levels and minimising hypoglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, recent work suggests that patients who have basal insulin or prandial insulin added to their oral therapy have better HbA1c control than those who receive biphasic insulin. In addition, the basal insulin regimen is associated with fewer hypoglycaemic episodes and less weight gain than the other two regimens (Holman et al., 2009). Basal insulin should be titrated to achieve normal fasting glucose levels, and the patient may be taught this self-titration protocol (Davies et al., 2005).

Treating hypertension

The co-existence of hypertension and diabetes dramatically increases the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Most important is the increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Tight control of blood pressure may be a more effective method of preventing complications in patients with type 2 diabetes than tight glycaemic control. It is recommended that, for patients with type 2 diabetes, the target blood pressure should be <140/80 mmHg, or for those with pre-existing kidney, eye or cerebrovascular damage the target should be reduced to <130/80 (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009). First-line blood-pressure-lowering therapy should be a once-daily, generically prescribed angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. Exceptions to this are people of African-Caribbean descent, in whom first-line therapy should be an ACE inhibitor plus either a diuretic or a generic calcium-channel blocker.

Treating obesity

Orlistat is licensed for use with a ‘mildly hypocalorific diet’ to treat obese people (BMI >30 kg/m2) or overweight patients with a BMI >28 kg/m2 and associated risk factors. It should be discontinued after 12 weeks if a 5% weight reduction since the start of treatment has not been achieved. Orlistat increases the amount of faecal fat excretion but is associated with a number of gastro-intestinal side effects such as oily leakage from the rectum, flatulence, faecal urgency and incontinence. A greater reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes has been observed in patients treated with both orlistat and lifestyle modification (Torgerson et al., 2004).

Patient care

Patient education

Patient involvement is paramount for the successful care of diabetes. This is highlighted in the national service standards for diabetes (Department of Health, 2002) which state that all patients, and carers, where appropriate, will be encouraged to develop a partnership with their clinicians to enable them to manage their diabetes and maintain a healthy lifestyle, often through shared care plans. Structured education for patients with type 2 diabetes is important and should be offered to every patient and/or their carer around the time of diagnosis. It is considered to be an integral part of diabetes care (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009).

Education will depend upon the individual patient and the availability of local resources. Individual tuition is preferable in the early stages after diagnosis and is usually delivered by a diabetes specialist nurse. The educational aspect of care is a gradual and ongoing process. At a later stage, group education can be effective and many patients appreciate and find support in meeting others who have the same disease. Many such programmes are multidisciplinary and involve doctors, nurses, dieticians, pharmacists and chiropodists. It is essential to involve the patient’s family and carers in the educational process. Patients can also obtain support and information from specialist organisations such as Diabetes UK (available at www.diabetes.org.uk/home.htm).

Patients require education and information about many subjects, ranging from general lifestyle advice through to knowledge about the medicines they are prescribed (Box 44.4).

Annual review

People with diabetes should attend their hospital clinic or primary care practice (if this service is offered locally) for an annual review to screen for diabetic complications. Monitoring and optimising glycaemic control are also undertaken although this should be done on a more regular basis, as should review of patients with known complications. The annual review is increasingly taking place in primary care, with referral to secondary care if required. The typical assessments undertaken at an annual review are described in Box 44.5.

Glycaemic management targets

Targets for pre-meal blood glucose of between 4 and 7 mmol/L and post-meal values of <10 mmol/L may be set for most patients, provided there is no significant hypoglycaemia risk. An optimal HbA1c target of 6.5% for most of those with type 2 diabetes has been suggested (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009). However, it is recommended that targets should be individualised and that for some a higher target would be more appropriate especially if there is a risk of hypoglycaemia at the lower target. For those with type 1 diabetes, the recommended target is less than 7.5% (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004).

The diabetes treatment goals in older people may be different and more conservative than in younger adults. For example, some elderly patients may have poor vision and limited manual dexterity, which may or may not be linked to a degree of cognitive impairment. Others may have multiple pathology and take a number of other medications. Therefore, the goals of therapy need to be both individual and realistic. In some people, they will involve only the optimisation of body weight, control of symptoms and avoidance of hypoglycaemia which has an increased risk of severe brain damage and may occur without the usual warning signs in the elderly. In others, reasonably tight control may be appropriate. There is, therefore, a difficult balance between the use of aggressive treatment with its associated risk of hypoglycaemia and the benefits of reducing complications to maintain an acceptable quality of life. Box 44.6 sets out some of the common therapeutic problems in diabetes.

Monitoring glycaemic control

Home monitoring

Type 2 diabetes

Questions

Answers

Answers

Answers

Questions

Answers

DAFNE Study Group. Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J.. 2002;325:746-749.

Davies M., Storms F., Shutler S., et al. Improvement of glycaemic control in subjects with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1282-1288.

Department of Health. National Service Framework for Diabetes: Standards. London: Department of Health, 2002.

Dormandy J.A., Charbonnel B., Eckland D.J.A., et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279-1289.

Holman R., Paul S., Bethel M., et al. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2008;359:1577-1589.

Holman R., Farmer A., Davies M., et al. Three-year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2009;361:1736-1747.

Joint British Societies Inpatient Care Group. The Management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Adults. NHS Diabetes; 2010. Available at: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/

Khan R., Buse J., Ferrannini E., et al. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diab. Care. 2005;28:2289-2304.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Type 1 Diabetes: Diagnosis and Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Children, Young People and Adults, Clinical Guideline 15.. London: NICE. 2004. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG015NICEguideline.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obesity: Guidance on the Prevention, Identification, Assessment and Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and Children, Clinical Guideline 43.. London: NICE. 2006. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG43NICEGuideline.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion for the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus, Technology Appraisal 57.. London: NICE. 2008. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12014/41300/41300.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Type 2 Diabetes: The Management of Type 2 Diabetes, Clinical Guideline 87.. London: NICE. 2009. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG87/NICEGuidance/pdf/English

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Neuropathic Pain: The Pharmacological Management of Neuropathic Pain in Adults in Non-Specialist Settings, Clinical Guideline 96.. London: NICE. 2010. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12948/47949/47949.pdf

Torgerson J.S., Hauptman J., Boldrin M.N., et al. XENical in the Prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects (XENDOS) Study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155-161.

Turnbull F., Abraira C., Anderson R., et al. Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2288-2298.

World Health Organization. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. 2006. Available at: www.who.int/diabetes/publications/en

Aldhahi W., Hamdy O. Adipokines, inflammation, and the endothelium in diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep.. 2003;3:293-298.

Diabetes UK in partnership with NHS diabetes. Putting Feet First. 2009. Available at: http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Documents/Reports/Putting_Feet_First_010709.pdf

Fowler D., Rayman G. Safe and Effective Use of Insulin in Hospitalised Patients. 2010. Available at: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/

Gerstein H.C., Miller M.E., Byington R.P., et al. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Study Group, Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2008;358:2545-2559.

Joint British Societies Inpatient Care Group. The Hospital Management of Hypoglycaemia in Adults with Diabetes. NHS Diabetes; 2010. Available at: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/

Joint British Societies Inpatient Care Group. The Management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Adults. NHS Diabetes; 2010. Available at: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/

Lipsky B.A., Berendt A.R., Gunner Deery H., et al. Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guidelines – diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2004;39:885-910.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Liraglutide for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. London: NICE; 2010. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13248/51259/51259.pdf

Patel A., MacMahon S., Chalmers J., et al. Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) Collaborative Group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2008;358:2560-2572.

Royal Pharmaceutical Society and National Pharmacy Association. Integrating Community Pharmacy into the Care of People with Diabetes – A Practical Resource. Royal Pharmaceutical Society and National Pharmacy Association; 2010. Available at: http://www.npa.co.uk/Documents/Docstore/NPA-Publications/Integrating_community_pharmacy_into_the_care_of_people_with_diabetes.pdf