17 Diabetes and other metabolic disorders

Introduction

The study of metabolism (Box 17.1) began as long ago as the fifteenth century bc, with the first description of diabetes in the Ebers Papyrus. Metabolic diseases comprise a variety of disorders encompassing a number of medical specialties. They contribute significantly to mortality and morbidity, predominantly from cardiovascular disease. Diabetes and metabolic disorders have become more prevalent in both developed and developing countries, leading to a significant burden of chronic disease and complications related to those diseases. This increased prevalence is related to excessive calorific intake coupled with reduced physical activity. Whereas in the past metabolic diseases such as diabetes were deemed diseases of the rich, in developed countries they are now frequently diseases of lower social class, as access to healthier foods may be expensive and difficult.

The major metabolic disorders considered in this chapter are:

Diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a classification of diabetes mellitus based on its pathogenesis (Table 17.1). The two predominant classes of diabetes are type 1 and type 2, and clinical differences between the two are listed in Table 17.2. Type 1 is characterized by absolute insulin deficiency due to autoimmune-mediated pancreatic islet cell destruction. In contrast, type 2 diabetes is associated with a variable degree of tissue insulin resistance, leading – at least in the early stages – to high plasma insulin levels, then subsequently to relative insulin deficiency as pancreatic islet cell function fails to overcome this resistance. The diagnostic criteria for disorders of glucose metabolism based on the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test are shown in Table 17.3. Note that glycosuria itself (glucose in the urine) is not a reliable diagnostic test for diabetes mellitus.

Table 17.1 The World Health Organization classification of diabetes mellitus

| Type | Common subtypes/pathogenesis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Destruction of pancreatic islet cells leading to insulin deficiency | Insulin |

| Type 2 | Ranges from predominantly insulin resistance with relative insulin deficiency (often associated with obesity) to predominantly insulin deficiency | Diet/oral hypoglycaemic agents/insulin |

| Other types | ||

| Genetic defects of β-cell function | Diabetes associated with glucokinase, hepatic nuclear factor (HNF) 1α, HNF1β, HNF4α, Neurod1 and insulin promotor factor mutations (all previously grouped under maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)) Mitochondrial diabetes |

Tablets or insulin depending upon genetic defect |

| Genetic defects of insulin action | Insulin-resistance syndromes (type A insulin resistance, leprechaunism, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome lipoatrophic diabetes) | Insulin-sensitizing agents and insulin |

| Diseases of the exocrine pancreas | Fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes, pancreatitis, trauma/pancreatectomy, neoplasia, cystic fibrosis, haemochromatosis, others | Frequently insulin required |

| Endocrinopathies | Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, phaeochromocytoma, glucagonoma, hyperthyroidism, somatostatinoma, others | Treatment of underlying cause |

| Drug or chemical induced | Glucocorticoids, α-adrenergic agonists, β-adrenergic agonists, thiazides, interferon-α therapy | Avoid |

| Uncommon forms of immune-mediated diabetes | Insulin autoimmune syndrome (antibodies to insulin), anti-insulin receptor antibodies, ‘stiff man’ syndrome | Variable |

| Other genetic syndromes associated with diabetes | Down’s, Friedreich’s ataxia, Huntington’s chorea, Klinefelter’s, Lawrence-Moon-Biedl, myotonic dystrophy, porphyria, Prader-Willi, Turner’s, Wolfram’s | Variable |

| Gestational diabetes | Diet/insulin | |

Table 17.2 Clinical differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes

| Type 1 | Type 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Ketosis prone | Yes | Uncommon |

| Insulin requirement | Yes (absolute insulin deficiency) | Often later in disease (insulin resistance ± deficiency) |

| Onset of symptoms | Acute | Often insidious |

| Obese | Uncommon | Common |

| Age at onset (years) | Usually <30 | Usually >30 |

| Family history of diabetes | 10% | 30% |

| Concordance in monozygotic twins | 30-50% | 90-100% |

It has long been recognized that many people have a clustering of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Thus, the term metabolic syndrome has been coined, with various pseudonyms of syndrome X or insulin resistance syndrome. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of the metabolic syndrome are shown in Box 17.2. People with the syndrome are at high risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The condition is common among certain ethnic groups (African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Asian Indians, Australian Aboriginals), and features can be present for up to 10 years before hyperglycaemia is detected. Vigorous treatment can reduce mortality and morbidity from cardiovascular disease.

Box 17.2 The International Diabetes Federation definition of metabolic syndrome

For a person to be defined as having the metabolic syndrome they must have:

Plus any two of the following four factors:

Presenting symptoms of diabetes

Polyuria, polydipsia and nocturia

Other conditions can cause polyuria and polydipsia (Table 17.4). Diabetes insipidus (DI) is characterized by loss of renal concentrating capacity, owing to either loss of secretion of antidiuretic hormone (arginine vasopressin) from the posterior pituitary gland (cranial DI) or to poor renal tubular responsiveness to antidiuretic hormone (nephrogenic DI). This leads to loss of free water which, if uncorrected by increased water ingestion, can lead to severe dehydration and plasma hypertonicity. Electrolyte disturbance, such as hypercalcaemia or hypokalaemia, can impair antidiuretic hormone action and hence lead to polyuria and polydipsia. In addition, polyuria and nocturia are common symptoms of chronic renal failure.

| Osmotic diuresis | Diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, drugs |

| Polydipsia | Psychogenic |

| Lack of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) | Cranial diabetes insipidus due to: idiopathic, surgery, pituitary/hypothalamic tumour, familial, postpartum |

| Failure of response to ADH | Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus due to: primary, renal tubular disorders, hypokalaemia, hypercalcaemia, drugs |

Other important aspects of a diabetic history

Diet and lifestyle history

Regularity of meals – three meals a day is ideal.

Regularity of meals – three meals a day is ideal.

Content of fatty/greasy foods – particularly discourage saturated (animal) fats, as this type of fat is linked to heart disease.

Content of fatty/greasy foods – particularly discourage saturated (animal) fats, as this type of fat is linked to heart disease.

Content of fruit and vegetables – at least five portions a day are recommended.

Content of fruit and vegetables – at least five portions a day are recommended.

Content of sugar and sugary foods – avoid carbonated drinks, cakes, sweets and biscuits.

Content of sugar and sugary foods – avoid carbonated drinks, cakes, sweets and biscuits.

Content of salt – a high salt intake can lead to hypertension.

Content of salt – a high salt intake can lead to hypertension.

Alcohol intake – a maximum of two units of alcohol per day for a woman and three units per day for a man.

Alcohol intake – a maximum of two units of alcohol per day for a woman and three units per day for a man.

Symptoms of complications of diabetes

Chronic complications of diabetes mellitus can be usefully subdivided into large blood vessels (macrovascular), small blood vessels (microvascular) and others (Table 17.5).

| Macrovascular | Coronary heart disease Peripheral vascular disease Cerebrovascular disease |

|

| Microvascular | Retinopathy |

Symptoms of macrovascular disease

The features of ischaemic heart disease are described elsewhere (see Ch. 11). People with diabetes have fewer, less severe symptomatic chest pains, possibly due to autonomic neuropathy leading to reduced deep pain sensation – so-called silent ischaemia. Thus, the only symptom of ischaemic heart disease in a diabetic subject may be breathlessness.

Peripheral vascular disease presents with claudication (Ch. 11). In addition, in patients with diabetes, a combination of peripheral neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease can lead to foot ulceration, particularly at sites of pressure (Fig. 17.2).

Cerebrovascular disease in diabetic patients can present with any stroke syndrome (Ch. 14). Transient ischaemic attacks are common.

Symptoms of microvascular disease

Diabetic retinopathy is frequently asymptomatic until it causes significant visual loss, which may be acute in onset (e.g. owing to a sudden retinal haemorrhage) or insidious (e.g. owing to cataract or maculopathy). Diabetic nephropathy is similarly asymptomatic until renal dysfunction becomes so severe that uraemia ensues (see Ch. 18). Uraemic symptoms include fatigue, breathlessness and tachypnoea, pleuritic chest pain due to pericarditis and pruritus. Heavy proteinuria may lead to the development of a nephrotic syndrome.

Mononeuropathies, particularly affecting the median nerve of the hand (carpal tunnel syndrome; see Ch. 14) are common in patients with diabetes. This frequently presents with paraesthesiae and numbness in the median nerve distribution of the hand (lateral two-and-half digits) and is again worse at night. Similar symptoms may occur in the foot (tarsal tunnel syndrome). Cranial mononeuropathies are rare, but palsies of cranial nerves III, VI and VII are seen in patients with diabetes, leading to blurred or double vision due to ophthalmoplegia, or a lower motor neurone facial palsy (Ch. 14). The pupillomotor fibres are usually spared in diabetic third nerve palsy.

Examination of the diabetic patient

General assessment

In the non-acute setting, measurement of weight and height to ascertain the body mass index (BMI) is of great importance in the assessment of the diabetic patient (Box 17.3). It is desirable for all patients with diabetes to undergo a full medical assessment once a year – the so-called diabetic annual review (Box 17.4).

Skin, nails and hands

Dermatological manifestations of diabetes are common. Fungal nail infections, particularly of the feet, are common, as are dermatophyte infections of the skin of the feet (tinea pedis). Staphylococcal skin infections leading to pustules, abscesses or carbuncles can also be seen. Other skins lesions seen in diabetes include necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (Fig. 17.3). This is a rare complication of diabetes, predominantly seen in young women aged 15-40 years. This presents as a painless red macule, usually over the anterior shin, which then heals with scarring to form a yellowish/brown lesion. The condition can be unsightly, and little effective treatment is available. Vitiligo is seen in a small number of patients with type 1 diabetes, reflecting its autoimmune nature.

Diabetic dermopathy is characterized by brown macules on the lower legs that heal to form atrophic, shiny white scars. A further skin lesion seen in patients with diabetes is granuloma annulare, pale, shiny rings and nodules usually seen on the hands (Fig. 17.4). Bullosis diabeticorum is a rare manifestation, characterized by tense blistering, mainly on the feet. Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by a dark velvety appearance in the axillae or neck of people with insulin resistance (Fig. 17.5) and frequently accompanies type 2 diabetes, but may occur in people with insulin resistance in the absence of diabetes.

Diabetic patients treated with insulin should have their injection sites examined for signs of lipohypertrophy (a physiological response to insulin injected near fat cells) (Fig. 17.6) or lipoatrophy (an allergic response to non-human insulins – now rarely seen) (Fig. 17.7).

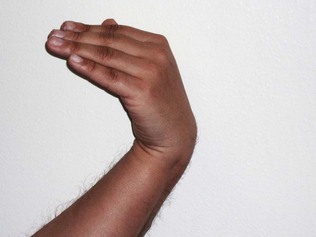

Diabetic cheiroarthropathy, or ‘stiff hand syndrome’ or ‘limited joint mobility’, is seen in some patients with longstanding diabetes. It is characterized by skin thickening and sclerosis of the tendon sheaths, leading to reduced joint mobility and the characteristic prayer sign (Fig. 17.8). Examination of the hands for signs of carpal tunnel syndrome (Ch. 14) is important if the patient has suggestive symptoms. Thus, the presence of Tinel’s sign (Fig. 17.9) and Phalen’s sign (Fig. 17.10) should be sought. Thenar eminence wasting may also be seen.

Eyes

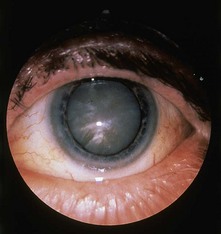

Examination of the eyes is mandatory in patients with diabetes. External examination may indicate signs of dyslipidaemia (corneal arcus and xanthelasmata; Fig. 17.11). A reduced pupillary response to light may indicate autonomic neuropathy. Visual acuity should be assessed yearly with a Snellen chart, and unexplained loss of acuity should be investigated. Funduscopy should be undertaken with pharmacological dilatation of the pupils in order to obtain an adequate view. Loss of the red reflex on funduscopy may indicate cataract formation, and the lens should be assessed for opacities (Fig. 17.12). The vitreous and retina should be examined carefully, starting from the optic disc and radiating into each quadrant of the eye. The macula is examined last, as this can be quite uncomfortable for the patient. The use of green light may aid the detection of microaneurysms. Ideally, all patients with diabetes should have annual fundal photography. A classification of diabetic retinopathy is shown in Box 17.5 (and see Figs 17.13–17.17).

Box 17.5 Characteristic features of diabetic retinopathy

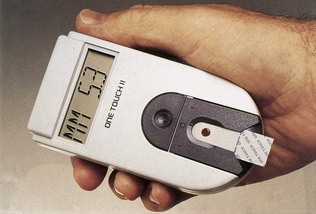

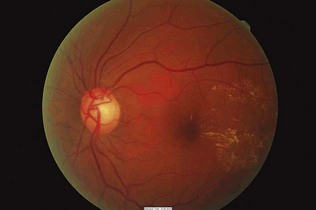

Figure 17.13 Background retinopathy (dot haemorrhages and microaneurysms) in the inferior nasal region.

(Courtesy of Dr Paul Dodson.)

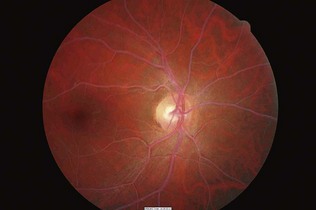

Figure 17.14 Preproliferative changes with multiple dot and blot haemorrhages and cotton wool spots.

(Courtesy of Dr Paul Dodson.)

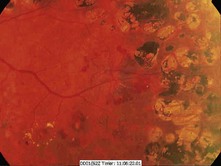

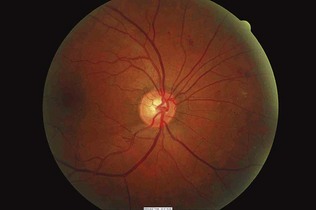

Figure 17.15 Retinal haemorrhage due to new vessel formation in severe proliferative retinopathy.

(Courtesy of Dr Paul Dodson.)

Feet

The feet of patients with diabetes should be examined at least once a year. Signs of deformity, callus (a sign of excessive pressure at this site), fungal infection especially between the toes, nail care and ulceration should be carefully assessed. Peripheral pulses and nail-fold refill should be assessed for signs of peripheral vascular disease. Nerve function should be assessed by testing vibration sense at the great toe, medial malleolus and knee, and testing fine touch on the toes, metatarsal heads, heels and dorsum of the feet with a 10-g monofilament (Semmes Weinstein monofilament) (Fig. 17.18). Loss of ankle jerks is also a sign of early diabetic peripheral sensory neuropathy.

Figure 17.18 Testing for neuropathy using a Semmes Weinstein monofilament giving standard 10 g of fine touch.

A complication of diabetic peripheral neuropathy is the neuropathic joint – Charcot neuroarthropathy (see Fig. 17.2). This usually affects the ankle and presents with a painless, swollen, hot red joint, sometimes with a history of minor local trauma. The natural history is of progressive deformity until the process settles, usually over a few months. Untreated, the joint develops severe deformity, which then puts the foot at high risk of ulceration, infection and amputation. Treatment is with immobilization in a plaster-cast boot, and intravenous bisphosphonates.

Investigation

Diagnosis of diabetes is based on a fasting plasma glucose or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), using the WHO criteria (see Table 17.3). Although clinically it is relatively simple to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, occasionally the diagnosis is not clear, especially in younger-onset type 2 diabetes without a family history. In these circumstances, the use of immunological tests such as anti-islet cell (ICA) or antiglutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody may be helpful. Positivity of either is a good indicator of autoimmune islet cell destruction (and hence probable type 1 diabetes), insulin deficiency and a subsequent requirement for insulin therapy.

Lipid disorders

The two circulating lipids, cholesterol and triglyceride, are transported within lipoproteins in the circulation. The apolipoproteins over the surface of these molecules enable their recognition by cells in organs such as the liver. The different types of lipoprotein are shown in Table 17.6.

| Lipoprotein | Apolipoprotein | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Chylomicrons | Apo B48 | Mainly triglyceride containing |

| Apo E | Manufactured by gut wall | |

| Apo C-II | Metabolized in liver/cells by lipoprotein lipase | |

| Very low density (VLDL) | Apo B100 | Main carrier of triglycerides in circulation |

| Apo E | Metabolized by lipoprotein lipase to IDL | |

| Intermediate density (IDL) | VLDL remnants which are removed by liver | |

| Low density (LDL) | Apo B100 | Main carrier of cholesterol in circulation 50% of circulating LDL is removed by liver each day Small dense LDL highly atherogenic Direct correlation of serum LDL levels with coronary heart disease (CHD) |

| High density (HDL) | Apo A1 | Transports 30% of total circulating cholesterol Inverse correlation of serum HDL levels with CHD |

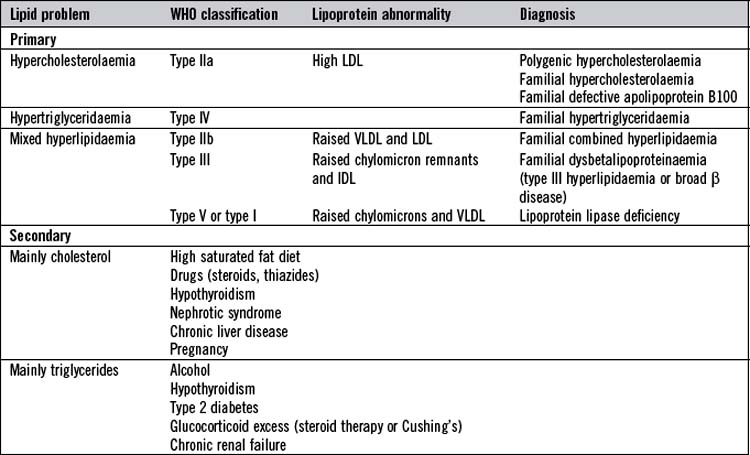

Lipid disorders are common and contribute significantly to the burden of cardiovascular disease. They can be conveniently divided into primary and secondary (Table 17.7). Primary lipid disorders are usually inherited, whereas secondary are acquired as a result of other medical disorders.

History

In the assessment of patients with lipid disorder, it is important to enquire about symptoms of ischaemic heart disease (chest pain history, admissions for ischaemic heart disease and any cardiological/cardiothoracic interventions), peripheral vascular disease (intermittent claudication) and cerebrovascular disease (transient ischaemic attacks, amaurosis fugax and strokes). Other cardiovascular risk factors should also be assessed. The smoking history is very important and a family history of premature vascular disease (under the age of 55 years) should be carefully sought. In familial hypercholesterolaemia, half of men and a fifth of women die before the age of 60 from coronary heart disease. Possible symptoms of secondary causes should also be assessed. Thus, symptoms of hypothyroidism (Ch. 16), diabetes (above), renal failure or nephrotic syndrome (Ch. 18) and liver disease (Ch. 12) should be sought. Alcohol intake and dietary history should also be assessed.

Diagnostic criteria for familial hypercholesterolaemia are shown in Box 17.6.

Box 17.6 The Simon Broome criteria for diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH)

Definite FH

Adult: total cholesterol >7.5 mmol/l or LDL cholesterol >4.9 mmol/l

Adult: total cholesterol >7.5 mmol/l or LDL cholesterol >4.9 mmol/l

Under 16 years: total cholesterol >6.7 mmol/l or LDL cholesterol >4.0 mmol/l

Under 16 years: total cholesterol >6.7 mmol/l or LDL cholesterol >4.0 mmol/l

Presence of tendon xanthomas in the patient or first- or second-degree relative

Presence of tendon xanthomas in the patient or first- or second-degree relative

DNA-based evidence of a mutation in the LDL receptor, apo B100 or PCSK9 genes

DNA-based evidence of a mutation in the LDL receptor, apo B100 or PCSK9 genes

Examination

The diagnostic hallmark of familial hypercholesterolaemia is tendon xanthomata. These are localized infiltrates of lipid-containing macrophages that resemble atherosclerotic plaques; they develop from the third decade onwards. The commonest sites are the Achilles tendon and the extensor tendons of the hands, particularly over the knuckles (Fig. 17.19). Other sites include the tibial tuberosities, at the site of insertion of the patellar tendon (subperiosteal xanthomata) or at the triceps tendon at the elbow.

Xanthelasmata are deposits of lipid in the skin of the eyelids, more commonly the upper rather than the lower (see Fig. 17.11). Although a dramatic sign, they are not present in the majority of patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia. More common is a corneal arcus, seen as a rim of lipid deposit around the iris (Fig. 17.11). This can be seen at any age, although it is more common in older people; only in the minority is this sign associated with hypercholesterolaemia.

The characteristic sign of hypertriglyceridaemia is eruptive xanthomata (Fig. 17.20). These are yellow nodules or papules that usually appear on the extensor surface of the elbows, knees, buttocks and back. Striate palmar xanthomas are yellowish discoloration of the skin creases, usually seen best in the hands, and are due to hypertriglyceridaemia. In severe forms of hypertriglyceridaemia, hepatosplenomegaly may be seen. Funduscopy in severe hypertriglyceridaemia may show lipaemia retinalis, characterized by optic pallor and the retinal vessels appearing white (Fig. 17.21).