162 Diabetes and Hyperglycemia

• Type 1 diabetes mellitus is defined as an absolute deficiency of insulin and type 2 as a relative insulin deficiency. These terms replace older definitions.

• The primary treatment modality for hyperglycemic emergencies is hydration with normal saline. In patients with diabetes, insulin therapy must follow evaluation of electrolyte levels.

• The majority of ketones in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis consist of β-hydroxybutyrate, but standard laboratory tests evaluate for acetoacetate. Hence, the standard “ketone” studies may not reflect this disease process.

• Intravenous bolus insulin has no role in any hyperglycemic condition or emergency, including diabetic ketoacidosis.

• Subcutaneous insulin is the preferred route for the treatment of hyperglycemia. A continuous intravenous insulin infusion may be warranted in patients with severe emergency conditions such as diabetic ketoacidosis; however, subcutaneous insulin has been suggested to be as efficacious for mild to moderate disease.

• Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis have a significant potassium deficit and require supplementation.

• Intravenous administration of dextrose-containing fluid should be initiated in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis when their glucose level is at or below 250 mg/dL to minimize the risk for hypoglycemia.

Diabetes Mellitis

Epidemiology

More than 23 million individuals in the United States have diabetes mellitus, and this number continues to increase at an accelerated rate, partially because of the worsening obesity epidemic in this country. In almost 6 million of these individuals, however, the diabetes is undiagnosed. In addition to the cost of life and morbidity associated with this disease, the financial expense is enormous. In 2007 the estimated direct and indirect cost of treating diabetes mellitus in the United States was $116 billion and $58 billion, respectively.1

Structure and Function

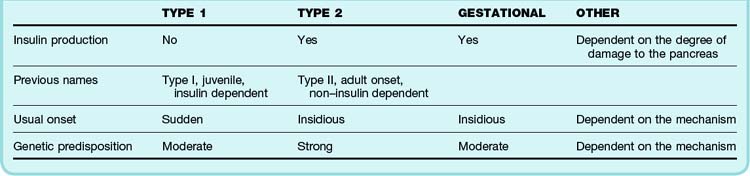

A newer classification system of diabetes mellitus reflects the pathophysiology of the disease and long-term treatment options. The new system identifies four types of diabetes mellitus: type 1, type 2, gestational diabetes, and “other” (Table 162.1).

The fourth category—“other”—is a catchall that contains all other causes of diabetes mellitus, including genetic anomalies causing malfunctioning insulin protein, insulin receptors, and beta cells in general, as well as other immune-mediated causes. Any significant insult to the exocrine pancreas—be it trauma, chronic pancreatitis, or cystic fibrosis—may result in this type of diabetes. Many common drug-induced causes of diabetes mellitus fall into this category (Box 162.1), as well as endocrinopathies such as hyperthyroidism, Cushing syndrome, and pheochromocytoma. Infectious causes include congenital rubella and cytomegalovirus. Less common causes include genetic disorders that may be associated with diabetes mellitus, including Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, Huntington chorea, and porphyria.

Diagnostic Testing

All patients with a history of diabetes mellitus should have an early point-of-care glucose assay performed when seen in the ED.2 At a minimum, diabetic patients with systemic complaints or complaints common to hyperglycemia require glucose testing at the time of first assessment. It is important to note that if serial tests are to be performed, there is a small but significant difference between capillary and venous blood glucose levels.3 Additionally, any patient with altered mental status or new neurologic concerns should also have glucose levels tested because patients with hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia may exhibit these changes.

The purpose of laboratory testing in a hyperglycemic patient is to differentiate simple hyperglycemia from DKA and less commonly from HHS. It is important to note that no reliable historical or physical examination findings are sensitive or specific enough to confirm or exclude these acute and serious complications of diabetes in hyperglycemic patients.4 A bicarbonate level below 15 mmol/L with an elevated anion gap (varies depending on the laboratory, but the upper limit is generally approximately 16 mEq/L) strongly suggests DKA. A more complete laboratory evaluation for hyper-glycemia includes venous pH, β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), and possibly serum osmolality. Additional laboratory tests may be necessary as dictated by the clinical picture. It has recently been suggested that acetoacetate (ACA), the standard ketone assayed for by serum and urine “ketone” assays, is neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of DKA.5,6

Hyperglycemia

Diagnosis and Diagnostic Testing

Complete a thorough evaluation for possible sources of infection in all diabetic patients.7 Chest radiography is indicated to search for pneumonia in patients with historical and physical examination findings suggesting pneumonia, patients in whom a thorough history and physical examination cannot be obtained, clinically ill patients, and patients at the extremes of age.

Infarction-related causes of hyperglycemia include acute coronary syndrome (acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina), pulmonary embolism, and cerebrovascular accident. It is important to note that acute coronary syndrome is very likely to be manifested in an atypical manner in diabetic patients (e.g., new-onset congestive heart failure without any history of chest pain or dyspnea without chest pain).8 Any hyperglycemic patient with these findings should undergo a complete ED evaluation for acute coronary syndrome. A computed tomography scan of the brain or chest may be required if cerebrovascular accident or pulmonary embolism is a concern.

Treatment

IV bolus administration of insulin has no role in the treatment of hyperglycemia. Administration of insulin via a continuous drip is not indicated, except in very special circumstances in which exceedingly tight glucose control is required (e.g., during a progressing cerebral vascular accident) for the treatment of simple hyperglycemia. In fact, very tight glucose control in an ill patient has been suggested to have no effect on patient outcome other than significantly increased rates of hypoglycemia.9 The dose of insulin depends on the degree of hyperglycemia after hydration and the patient’s previous exposure to insulin therapy. Patients with known diabetes treated with insulin therapy may be given their usual dose after hydration. Patients new to insulin may be given low-dose subcutaneous insulin with the goal of decreasing glucose to acceptable levels at a rate of 100 mg/dL/hr.

A guideline for subcutaneous regular insulin dosing is presented in Table 162.2. This guideline is appropriate for hyperglycemic patients who have little to no previous experience with subcutaneous insulin. Those managed with insulin regimens may do better with one approximating their typical dosage. In addition, this guideline assumes that the patient has first been rehydrated and remains hyperglycemic.

| GLUCOSE LEVEL | DOSAGE |

|---|---|

| >250 mg/dL | 2 units |

| >300 mg/dL | 4 units |

| >350 mg/dL | 6 units |

| >400 mg/dL | 8 units |

| >450 mg/dL | 10 units |

| >500 mg/dL | 12 units |

* See text for a discussion of modifications of this guideline. Patients treated with regular insulin regimens should be given their usual dosage if appropriate for their condition.

New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes

Box 162.2 summarizes the clinical and diagnostic findings in patients with new-onset diabetes. In the past these patients were admitted to the hospital without question and a new drug or insulin regimen started. This practice has changed in the last decade because it is now recognized that medications can be started in the outpatient setting without exposing these patients to the inherent risks associated with hospitalization.

Box 162.2

Diagnosis of New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is diagnosed in patients with symptoms of uncontrolled diabetes, including polyuria, polydipsia, and weight loss, and a random glucose level higher than 200 mg/dL.

Diabetes mellitus is also diagnosed in patients with a fasting plasma glucose level higher than 125 mg/dL.

Fasting glucose levels higher than 110 mg/dL suggest impaired glucose metabolism; these patients should be discharged and scheduled for follow-up with a primary care provider.

Fasting glucose levels higher than 95 mg/dL in pregnant patients are consistent with the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus.

Data from American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004;27:S5–10; and Metzger BE, Coustan DR. Summary and recommendations of the Fourth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. The Organizing Committee. Diabetes Care 1998;21(Suppl 2):B161–7.

Treatment and Disposition

The initial medication for patients with new-onset diabetes is most often a low-dose sulfonylurea. A good choice of sulfonylurea is glyburide (1.25 to 2.5 mg orally once a day) or glipizide (2.5 to 5 mg orally once a day). These doses may not allow strict glucose control but are appropriate early therapy and pose little risk for hypoglycemia. When starting these medications, patients should be instructed to take them with an early meal or breakfast and to eat regular meals throughout the day. Metformin (850 mg orally once a day) is an appropriate choice for initiating diabetes therapy when a nonsulfonylurea drug is preferred. This drug, when used alone in initial therapy, poses a very low risk for hypoglycemia and may be a good choice for obese patients.10

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

The signs and symptoms of patients with DKA seen in the ED can be incredibly variable. For this reason it is important to remember that although there is a classic manifestation of DKA, there are no typical findings. The emergency physician should not be lulled into a false sense of security by a hyperglycemic patient who “looks good.” DKA should be considered a spectrum of disease, and patients can progress from “looking good” to “being ill” very quickly. Thus any patient in the ED with hyperglycemia requires a laboratory evaluation.4

Epidemiology

The approximate incidence of DKA is 5 to 8 cases per 1000 diabetics per year. Mortality has remained approximately 4% to 5% for the last decade in patients in whom DKA is diagnosed and treatment begun early in the disease course. Some estimates of mortality in patients in whom diagnosis and treatment are delayed run as high as 14%.11 Other estimates suggest that in as many as 20% of patients DKA is misdiagnosed; these patients therefore have a significantly increased risk for death.

Clinical Presentation

The causes of DKA are many, and they are similar to those of hyperglycemia (Box 162.3). The onset may be due to any significant stressor (classically an infection or infarction) or may be due to a deficiency of insulin, usually because the insulin dosage is insufficient, oral therapy is ineffective, or the patient is not compliant with therapy. It is important to note that diabetic patients may have acute conditions—for example, patients with diabetes and pneumonia—and may therefore need increased insulin administration temporarily or DKA will develop; in these cases the cause of the ketoacidosis is both infection and inadequate insulin administration.

Differential Diagnosis, Diagnostic Testing, and Testing Pitfalls

The differential diagnosis of DKA is summarized in Box 162.4. In any patient who may have DKA, the laboratory evaluation shown in Box 162.5 should be performed. No single standard laboratory diagnosis has been established for DKA; however, any diagnosis should include the factors noted in Box 162.6. It should be stressed that the diagnosis of DKA is based mainly on clinical findings; although laboratory evaluation is important, common complicating factors often make laboratory diagnosis difficult. Each of the components of the laboratory diagnosis is fraught with limitations and qualifications.

Box 162.5 Recommended Laboratory Evaluation for Hyperglycemia

Basic chemistry panel (Na+, K+, Cl−, serum bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose)

Ketones (serum β-hydroxybutyrate preferred)

If diabetic ketoacidosis is suspected or confirmed, add magnesium, phosphate, ECG

If the initial glucose level is higher than 600 mg/dL or a hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state is suspected, add plasma osmolality

As clinically indicated, cardiac enzymes, serial ECG, lipase, ventilation-perfusion scan, CTPA, CT of the head

CT, computed tomography; CTPA, computed tomographic pulmonary angiography; ECG, electrocardiography.

Box 162.6 Classic Diagnostic Test Findings in Patients with Diabetic Ketoacidosis*

* The diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis will ideally be made with the above findings; however, it is important to note that the clinical scenario dictates the relative importance of each finding, as discussed in the text.

† β-Hydroxybutyrate is the preferred ketone, but most laboratories substitute blood acetoacetate.

Hyperglycemia is commonly considered the cornerstone of the work-up; however, DKA in the presence of “euglycemia” is not an uncommon finding. In fact, approximately 30% of patients with DKA have a glucose level lower than 300 mg/dL,12 and some studies suggest that the longer patients are in a state of DKA, the more likely they are to be euglycemic.13 The reasons for this are manyfold. Patients with DKA often have gastrointestinal disturbances that cause vomiting and therefore limited oral intake, with the result that liver glycogen stores will be depleted and gluconeogenesis, which may be inhibited during acidosis,14 will be the sole source of glucose production. It has also been suggested that patients with poorly controlled diabetes do not store glucose as liver glycogen as readily or efficiently as do nondiabetic individuals or patients whose disease is well controlled. Liver disease of any cause will also limit or prevent glycogen storage and gluconeogenesis.

Although the majority of patients have a low serum bicarbonate level and pH, as well as an elevated anion gap, approximately 10% will have at least one of these factors reported as normal.5 It should be noted that venous pH is perfectly acceptable and there is no reason to obtain an arterial sample.15

The final component of the diagnosis is the presence of ketones. As discussed previously, the majority of ketones are in the form of BHB, but the standard laboratory urine and serum examinations assay for ACA. Recent work has suggested that ACA is neither sensitive nor specific for DKA, whereas BHB appears to be very sensitive and specific for this disease.5,6,16 Additionally, ACA levels may not be high enough to be detected, especially in the dilute urine of a patient experiencing hyperglycemic osmotic diuresis. However, as the patient is rehydrated and treatment begins, serum BHB is converted to ACA. Thus, in a not-uncommon scenario, a hyperglycemic patient is initially negative for urine ketones but after rehydration and treatment begins to “suddenly spill” them and is falsely labeled as worsening and beginning to be in DKA when in fact the patient already was in DKA but the diagnosis was missed because the urine examination tested for the “wrong” ketone.

Treatment

A treatment plan for DKA is outlined in Box 162.7. Early treatment is similar to that for hyperglycemia. Patients usually exhibit moderate to severe dehydration and should receive NS. The average patient without a history of congestive heart failure or renal failure often requires 5 to 8 L of fluid over the course of the hospitalization. Potassium levels must be checked and hypokalemia corrected concurrent with the administration of insulin because patients may have significant (often hundreds of milliequivalents) total body potassium depletion. Insulin will drive extracellular potassium into cells and, because of the total body depletion, may cause an exaggerated serum hypokalemia that may lead to cardiac arrhythmia.

Box 162.7 Treatment Plan for Patients with Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Electrolytes

Insulin

Intravenous bolus insulin has no role in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis.

After the patient is hemodynamically stable, start a regular insulin drip at 0.05 to 0.1 U/kg/hr. Early evidence suggests that mild to moderate diabetic ketoacidosis may be treated with insulin subcutaneously.17

When the patient’s anion gap has resolved to less than 15 mEq/L, administer a long-acting insulin (e.g., glargine) subcutaneously at the patient’s usual dose or as below:

Other electrolytes such as magnesium and phosphorus are less crucial and may be administered as usual. Correction of even moderate hypophosphatemia has not been shown to be beneficial in these patients. It is therefore recommended that only severe hypophosphatemia (<1 mmol/L) or moderate hypophosphatemia with clinical findings such as respiratory muscle weakness or cardiomyopathy be corrected.18 If necessary, potassium chloride may be replaced with potassium phosphate for this purpose. Hypomagnesemia may be corrected with IV magnesium sulfate.

Bicarbonate therapy rarely has a place in the treatment of patients with DKA. Although administration of bicarbonate to a patient with metabolic acidosis may seem logical, it is rarely helpful and may cause multiple, significant complications.19,20 Because bicarbonate cannot cross the blood-brain barrier but carbon dioxide can, administration of bicarbonate may allow increased carbon dioxide to enter cerebrospinal fluid and cause a paradoxic cerebrospinal fluid acidosis. Additionally, bicarbonate administration may worsen the hypokalemia by driving potassium into cells. Studies have clearly shown administration of bicarbonate to a patient with DKA and a pH of at least 6.8 to be of no benefit.19 No studies specifically support the administration of bicarbonate for any pH in patients with DKA. If bicarbonate administration has any role, it may be only in a patient with shock and impending or present cardiovascular collapse secondary to marked acidosis and dehydration.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Pitfalls in the Treatment of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Administration of insulin before correcting potassium deficiencies. This can lead to clinically significant hypokalemia and cardiac arrhythmias.

Not repeating serum chemistry panels every 2 hours and beside glucose testing every hour to adjust the administration of fluids, insulin, and electrolytes. This should be continued for at least 2 hours after discontinuing the insulin drip.

Administration of insulin should begin only after the initial hydration and electrolyte correction. IV bolus insulin has no role in treatment. Administration of IV bolus insulin leads to a supraphysiologic serum insulin level that can cause a significant drop in plasma potassium levels and cardiac arrhythmias.21 It may also cause hypoglycemia and cerebral and pulmonary edema, and it has been theorized to lead to changes in gene-regulated protein synthesis that may exert its effects for weeks.22,23 Additionally, because IV regular insulin has a plasma half-life of less than 5 minutes, a continuous, low-dose infusion reaches a steady-state level quickly.24

The standard insulin protocol has been to start a drip of regular insulin at 0.1 U/kg. More recently it has been suggested that lower doses may work as well with less risk for hypokalemia, and some authors have even suggested the use of subcutaneous insulin.25

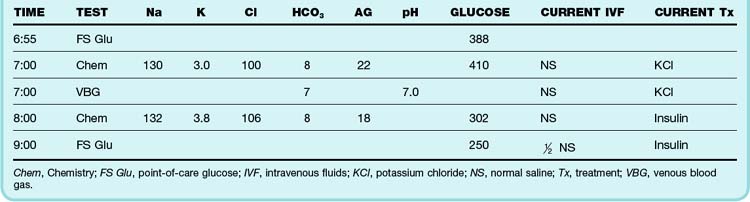

Patients treated by insulin drip are at risk for hypoglycemia and hypokalemia, as mentioned previously, and therefore require regular electrolyte and glucose assays. The author recommends alternating a bedside glucose assay with a basic chemistry panel every hour and charting a flow sheet as shown in Table 162.3. Potassium can then be supplemented as necessary. The patient’s fluid should be changed to D5  NS (5% dextrose solution in

NS (5% dextrose solution in  NS) when the glucose level reaches 250 mg/dL. When the anion gap has resolved to 15 mEq/L or less, the patient should be given subcutaneous insulin at the usual dose or at a dose similar to those detailed in Box 162.7. Two hours later, the insulin drip can be discontinued; this approach allows subcutaneous insulin administration and the insulin drip to overlap by 2 hours.

NS) when the glucose level reaches 250 mg/dL. When the anion gap has resolved to 15 mEq/L or less, the patient should be given subcutaneous insulin at the usual dose or at a dose similar to those detailed in Box 162.7. Two hours later, the insulin drip can be discontinued; this approach allows subcutaneous insulin administration and the insulin drip to overlap by 2 hours.

Cerebral edema has long been the most feared complication of pediatric DKA. It occurs in approximately 1% of all cases but carries a mortality rate quoted to be as high as 50%. It has long been held that the treatment regimen, especially rapid rehydration, has been responsible for this complication. However, no data support this belief, and the current literature strongly suggests that there is no casual relationship between cerebral edema in pediatric patients with DKA and their treatment regimen17; instead, it is more likely that the degree of illness better correlates with the likelihood of this deadly complication. Treatment is similar to that for other causes of cerebral edema while the standard management of DKA continues.

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State

HHS is a comparatively uncommon but nonetheless serious complication of diabetes mellitus, with a mortality rate as high as 50%.11 It has had many other names in the past, including hyperosmolar nonketotic coma, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar coma, and hyperosmolar nonacidotic diabetes mellitus. The term hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state is more appropriate because not all patients with HHS are nonketotic and certainly not all are in coma or have altered mental status.26

Pathophysiology

Like DKA, HHS is initiated by a relative lack of insulin; however, the insulin deficiency is usually significantly less profound than that of DKA. Very low levels of insulin (or a low ratio of insulin to counterregulatory hormones) are necessary to prevent ketoacidosis; as insulin levels increase, further gluconeogenesis and glycogen metabolism are sequentially switched off. Because just small amounts of insulin are needed to prevent ketosis, only limited amounts of ketones are produced during HHS. The patient becomes successively more dehydrated secondary to the glucose-driven osmotic diuresis. The dehydration may eventually lead to impaired renal function and an inability to excrete the continually produced glucose, thereby resulting in severe hyperglycemia.27

Clinical Presentation

Despite many similarities between DKA and HHS, they differ in some very important ways (Table 162.4). As discussed earlier in regard to DKA, patients with HHS may often have atypical findings. The diagnosis of HHS is associated with glucose levels higher than 600 mg/dL, but the average glucose level is approximately 900 mg/dL, and it is not uncommon for the glucose level to be well in excess of 1000 mg/dL.

Table 162.4 Comparison of Classic Laboratory Findings in Patients with Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State

| FINDING | DKA | HHS |

|---|---|---|

| Osmolarity (mOsm/L) | Normal (280-300) | >320 with AMS |

| >350 with normal MS | ||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | Usually 250-600 | >600 |

| Insulin | Absent to low | Low to normal |

| Ketones (BHB) | Present | Absent |

| pH | <7.35 | Mildly low to normal |

| HCO3 | <15 | Mildly low to normal |

| Onset | Variable | Usually slow onset over days to weeks |

AMS, Altered mental status; BHB, β-hydroxybutyrate; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; HHS, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state; MS, mental status.

Diagnostic Testing and Testing Pitfalls

Diagnostic criteria for HHS are summarized in Box 162.8. As with DKA, it needs to be stressed that the diagnosis is based mainly on clinical findings; although laboratory evaluation is important, common complicating factors often make laboratory diagnosis difficult.

Box 162.8 Diagnostic Testing Criteria for Patients with Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State

Absence of ketosis is required to differentiate pure HHS from pure DKA. However, many patients lie in a spectrum between these two entities and may form a small amount of BHB. Additionally, because most laboratories actually assay for ACA, as discussed earlier, mild ketoacidosis is common secondary to anorexia and vomiting. Another classic finding of HHS is a “normal pH.” However, it is not uncommon to have a mild acidotic hyperosmolar state secondary to lactic acidosis caused by lack of perfusion to peripheral tissues from the severe dehydration. In fact, approximately one half of patients with HHS are believed to have a mild anion gap metabolic acidosis.28 In addition, the pH may temporarily decrease further during the initial fluid resuscitation as the peripherally produced lactic acid is returned to the liver for processing.

Treatment

A treatment plan for HHS is summarized in Box 162.9. As with simple hyperglycemia and DKA, the primary treatment is fluid resuscitation with NS. The average fluid deficit is 9 L.29 Resuscitation includes administration of boluses of 1 to 2 L of NS initially, followed by administration of NS until there is improvement in vital signs that suggests improved hemodynamics, as indicated by the onset of urine output and an improved clinical hydration state. Fluids then can be changed to  NS.

NS.

Box 162.9 Treatment Plan for Patients with Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State

Insulin

Intravenous bolus insulin has no role in the treatment of patients with hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), nor does insulin of any kind have a role during the early resuscitation phase of treatment.

After early fluid and electrolyte administration and when the patient is hemodynamically stable, start a regular insulin drip at 0.05 to 0.1 U/kg/hr. Note that some authorities suggest significantly lower doses, starting around 2 U/hr, in an average-sized adult and adjusting the rate based on the decrease in glucose levels.

Do not allow glucose levels to decrease at a rate greater than 100 mg/dL/hr.

Electrolytes

• Potassium replacement (oral administration is preferred, but the intravenous route can be used if the patient cannot tolerate oral replacement) should be started as follows:

• Magnesium replacement—unless the patient is in renal failure and not able to produce urine, early administration of magnesium is mandatory:

• Patients being treated for HHS are at risk for refeeding syndrome and should receive thiamine supplementation.

• When the patient has clinically improved with a glucose level lower than 300 mg/dL, intravenous insulin may be switched to subcutaneous insulin in a manner similar to that for diabetic ketoacidosis (see Box 162.7).

1. Patients should have approximately 50% of their fluid deficit met in the first 12 hours of treatment.

2. Glucose levels should fall no faster than 100 mg/dL/hr after the initial resuscitation is completed.

Phosphate and magnesium supplementation may be more essential in the management of HHS than in the treatment of DKA. Because HHS characteristically develops over a period of days to weeks, total body stores of these electrolytes are more likely to have been significantly affected by the osmotic diuresis. Although compelling studies are lacking, it is probably of greater urgency to supplement these electrolytes early in the course of treatment.30,31

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Pitfalls in the Treatment of Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State

Hypernatremia may be caused by failure to change normal saline to  normal saline after the resuscitation phase of treatment has concluded.

normal saline after the resuscitation phase of treatment has concluded.

Early administration of insulin may lead to:

Failure to replete electrolytes during fluid administration may lead to cellular and cerebral edema and cardiovascular instability.

Seizures occurring in a patient in a hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state should not be treated with phenytoin (Dilantin) because this drug is known to decrease endogenous insulin secretion.

1 National Diabetes Fact Sheet. 2007. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publication.

2 Degroote NE, Pieper B. Blood glucose monitoring at triage. J Emerg Nurs. 1993;19:131–133.

3 Boyd R, Leigh B, Stuart P. Capillary versus venous bedside blood glucose estimations. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:177–179.

4 Menjivar E, Graber MN, Watts S. Physician and nurse clinical impression does not rule out diabetic ketoacidosis. Las Vegas, Nev: American Academy of Emergency Medicine Scientific Assembly; 2010. February 15-17

5 Graber MN, Watts S. The utility of serum and urine acetoacetate in the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis. Sonoma, Calif: 13th Annual Western Regional SAEM Meeting; 2010. March 19-20

6 Torres J, Rampal D, Graber MN. Ketones in the diagnosis of DKA: beta-hydroxybutyrate is superior to acetoacetate. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:582.

7 Joshi N, Caputo GM, Weitekamp MR, et al. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1906–1912.

8 Singer DE, Moulton AW, Nathan DM. Diabetic myocardial infarction: interaction of diabetes with other preinfarction risk factors. Diabetes. 1989;38:350–357.

9 Brunkhorst FM, Engel CE, Bloos F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N. Engl J Med. 2008;358:125–139.

10 Lee A, Morley JE. Metformin decreases food consumption and induces weight loss in subjects with obesity with type II non–insulin-dependent diabetes. Obes Res. 1998;6:47–53.

11 . Acute metabolic complications in diabetes. National Diabetes Data Group. Fishbein H, Palumbo PJ. Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 1995:283–291.

12 Munro JF, Campbell IW, McCuish AC, et al. Euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis. BMJ. 1973;2:578–580.

13 Burge MR, Hardy KJ, Schade DS. Short term fasting is a mechanism for the development of euglycemic ketoacidosis during periods of insulin deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1192–1198.

14 Iles RA, Cohen RD, Rist AH, et al. Mechanism of inhibition by acidosis of gluconeogenesis from lactate in rat liver. Biochem J. 1977;164:185–191.

15 Kreshak A, Chen EH. Arterial blood gas analysis: are its values needed for the management of diabetic ketoacidosis? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:550–551.

16 Arora S, Long T, Henderson SO. Comparing beta-hydroxybutyrate testing to urine dip for identifying diabetic ketoacidosis at triage. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;45(4):S93–S94.

17 Umpierrez GE, Latif K, Stoever J, et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous insulin lispro versus continuous intravenous regular insulin for the treatment of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Am J Med. 2004;117:291–296.

18 Wilson HK, Keuer SP, Lea AS, et al. Phosphate therapy in diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:517–520.

19 Morris LR, Murphy MB, Kitabchi AE. Bicarbonate therapy in severe diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:836–840.

20 Green SM, Rothrock SG, Ho JD, et al. Failure of adjunctive bicarbonate to improve outcome in severe pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:41–48.

21 Fisher JN, Shahshahani MN, Kitabchi AE. Diabetic ketoacidosis: low-dose insulin therapy by various routes. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:238–241.

22 Schade DS, Eaton RP. Dose response to insulin in man: differential effects on glucose and ketone body regulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977;44:1038–1053.

23 Carroll MF, Schade DS. Ten pivotal questions about diabetic ketoacidosis. Answers that clarify new concepts in treatment. Postgrad Med. 2001;10:89–92. 95

24 Brown TB. Cerebral oedema in childhood diabetic ketoacidosis: is treatment a factor. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:141–144.

25 Fort P, Waters SM, Lifshitz F. Low-dose insulin infusion in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis: bolus versus no bolus. J Pediatr. 1980;96:36–40.

26 Carroll P, Matz R. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus in adults: experience in treating diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar nonketotic coma with low-dose insulin and a uniform treatment regimen. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:579–585.

27 Brodsky WA, Rapaport S, West CD. The mechanism of glycosuric diuresis in diabetic man. J Clin Invest. 1950;29:1021–1032.

28 Matz R. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1468–1476.

29 Siperstein M. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar coma. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1992;21:415–432.

30 Solomon SM, Kirby DF. The refeeding syndrome: a review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1990;14:90–97.

31 Matz R. Magnesium: deficiencies and therapeutic uses. Hosp Pract (Off Ed). 1993;28:79–82. 85–7, 91–2

NS after the patient’s clinical hydration status begins to improve (usually after 2 to 3 L).

NS after the patient’s clinical hydration status begins to improve (usually after 2 to 3 L). NS to D5

NS to D5  NS when the patient’s glucose level reaches 250 mg/dL.

NS when the patient’s glucose level reaches 250 mg/dL.

NS when approximately half the fluid deficit is replaced during the first 12 hours of treatment

NS when approximately half the fluid deficit is replaced during the first 12 hours of treatment