Developmental problems and the child with special needs

Any child whose development is delayed or disordered needs assessment to determine the cause and management. Neurodevelopmental problems present at all ages, with an increasing number now recognised antenatally (Table 4.1). Many are identified in the neonatal period because of abnormal neurology or dysmorphic features. During infancy and early childhood, problems often present at an age when a specific area of development is most rapid and prominent, i.e. motor problems during the first 18 months of age, speech and language problems between 18 months and 3 years and social and communication disorders between 2 and 4 years. Abnormal development may be caused not only by neurodevelopmental problems (Table 4.2) but also by ill health or if the child’s physical or psychological needs are not met.

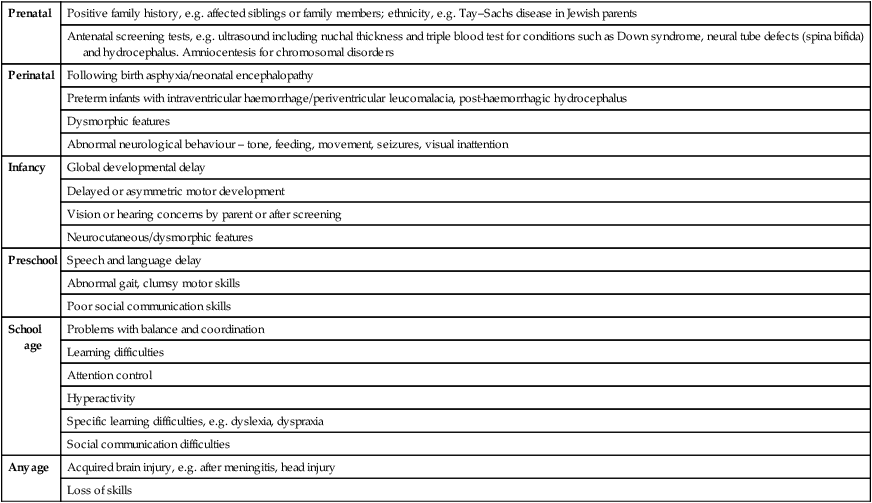

Table 4.1

Features that may suggest neurodevelopmental concerns by age

| Prenatal | Positive family history, e.g. affected siblings or family members; ethnicity, e.g. Tay–Sachs disease in Jewish parents |

| Antenatal screening tests, e.g. ultrasound including nuchal thickness and triple blood test for conditions such as Down syndrome, neural tube defects (spina bifida) and hydrocephalus. Amniocentesis for chromosomal disorders | |

| Perinatal | Following birth asphyxia/neonatal encephalopathy |

| Preterm infants with intraventricular haemorrhage/periventricular leucomalacia, post-haemorrhagic hydrocephalus | |

| Dysmorphic features | |

| Abnormal neurological behaviour – tone, feeding, movement, seizures, visual inattention | |

| Infancy | Global developmental delay |

| Delayed or asymmetric motor development | |

| Vision or hearing concerns by parent or after screening | |

| Neurocutaneous/dysmorphic features | |

| Preschool | Speech and language delay |

| Abnormal gait, clumsy motor skills | |

| Poor social communication skills | |

| School age | Problems with balance and coordination |

| Learning difficulties | |

| Attention control | |

| Hyperactivity | |

| Specific learning difficulties, e.g. dyslexia, dyspraxia | |

| Social communication difficulties | |

| Any age | Acquired brain injury, e.g. after meningitis, head injury |

| Loss of skills |

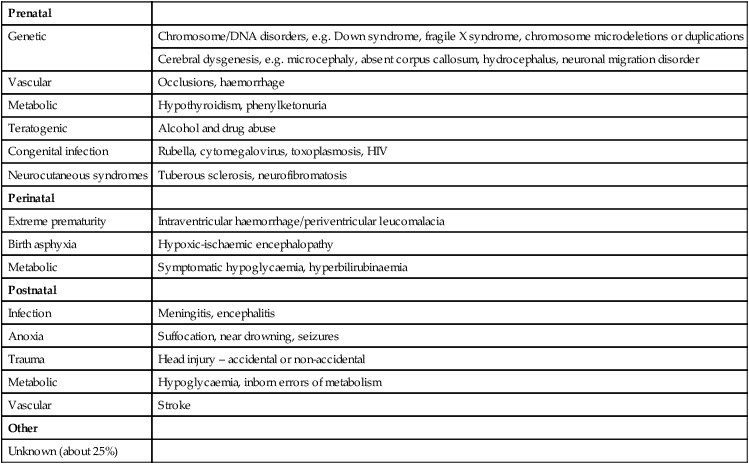

Table 4.2

Conditions which cause abnormal development and learning difficulty

| Prenatal | |

| Genetic | Chromosome/DNA disorders, e.g. Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, chromosome microdeletions or duplications |

| Cerebral dysgenesis, e.g. microcephaly, absent corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, neuronal migration disorder | |

| Vascular | Occlusions, haemorrhage |

| Metabolic | Hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria |

| Teratogenic | Alcohol and drug abuse |

| Congenital infection | Rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, HIV |

| Neurocutaneous syndromes | Tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis |

| Perinatal | |

| Extreme prematurity | Intraventricular haemorrhage/periventricular leucomalacia |

| Birth asphyxia | Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy |

| Metabolic | Symptomatic hypoglycaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia |

| Postnatal | |

| Infection | Meningitis, encephalitis |

| Anoxia | Suffocation, near drowning, seizures |

| Trauma | Head injury – accidental or non-accidental |

| Metabolic | Hypoglycaemia, inborn errors of metabolism |

| Vascular | Stroke |

| Other | |

| Unknown (about 25%) |

The site and severity of brain damage influences the clinical outcome, i.e. whether specific or global developmental delay, learning and/or physical disability.

When performing a clinical examination on a young child with a developmental problem:

• Ask the parent what their child can and cannot do. Start at a level below what a child is likely to be able to do to retain confidence of the parent and child.

• Observe the child from the first moment seen.

• Make it fun. Your examination should be perceived as a game by the child, although they may not always follow your rules.

• Toys to use are cubes, a ball, car, doll, pencil, paper, pegboard, miniature toys, picture book. Adapt their use to the child.

• Formulate a developmental picture in terms of gross motor; vision and fine motor; hearing, speech and language; and social, emotional and behaviour. As you become more confident you will screen all these skills simultaneously.

• At the end of developmental screening you should be able to describe what a child is able to do and what the child cannot do, if the abilities are within normal limits for age and, if not, which developmental fields are outside the normal range.

• Clinical signs to look for that may aid diagnosis or guide investigation are:

– patterns of growth: height, weight, head circumference with centile plotting

– dysmorphic features: face, limbs, body proportions, cardiac, genitalia

– skin: neurocutaneous stigmata, injuries, cleanliness

– central nervous system examination: abnormal posture/symmetry, wasting, power and tone, deep tendon reflexes, clonus, plantar responses, sensory examination, cranial nerves

– cardiovascular examination: abnormalities are associated with many dysmorphic syndromes

– visual function and ocular abnormalities

– hearing: by questioning parents about hearing and language development and checking if neonatal hearing screening was done

– patterns of mobility, dexterity, hand dominance, communication and social skills, general behaviour

Many examination findings can be predicted from observation of functional skills.

Abnormal development – key concepts

The terminology can be confusing, but:

• Delay – implies slow acquisition of all skills (global delay) or of one particular field or area of skill (specific delay), particularly in relation to developmental problems in the 0–5 years age group

• Learning difficulty – used in relation to children of school age and may be cognitive, physical, both or relate to specific functional skills

The following are agreed definitions:

• Impairment – loss or abnormality of physiological function or anatomical structure

• Disability – any restriction or lack of ability due to the impairment

• Disadvantage – this results from the disability, and limits or prevents fulfilment of a normal role. It is situationally specific; a child with a learning disability may for example be a good skier or enjoy swimming.

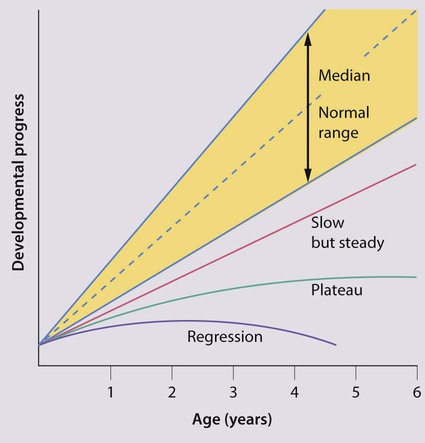

The pattern of abnormal development (global or specific) can be categorised as (Fig. 4.1):

The severity can be categorised as:

Other features of developmental delay are:

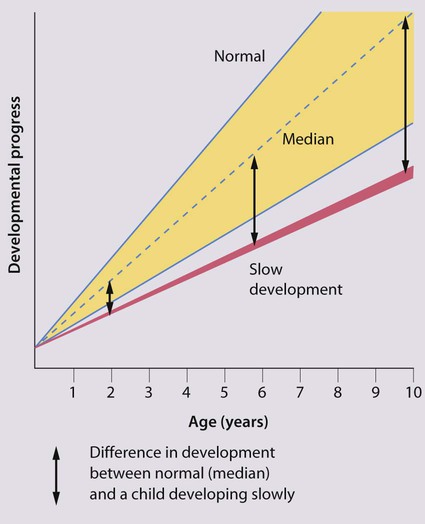

• The gap between normal and abnormal development becomes greater with increasing age and therefore becomes more apparent over time (Fig. 4.2).

• It may be the presentation of a wide variety of underlying conditions (Table 4.2).

• The site and severity of brain damage influences the clinical outcome, i.e. whether there will be specific or global developmental delay, learning and/or physical disability.

• It may be genetic, with important implications for the family.

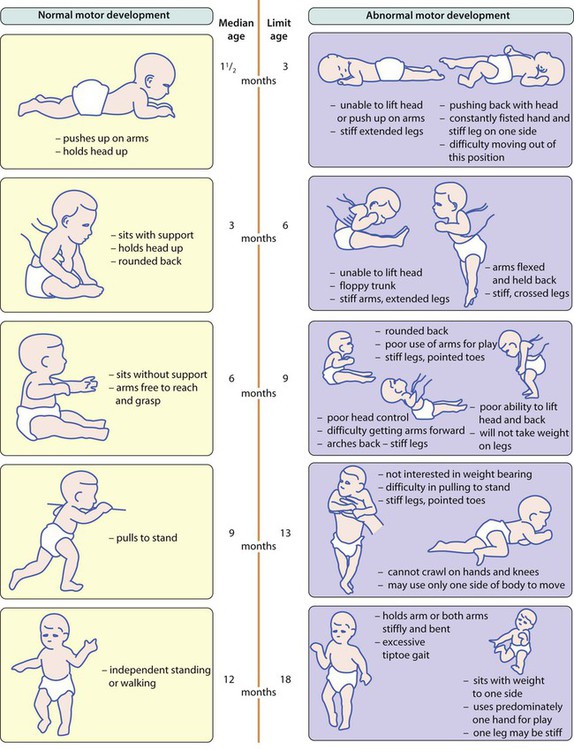

• There is a wide age band across which it can be normal to achieve a developmental skill. Limit ages denote beyond the normal range.

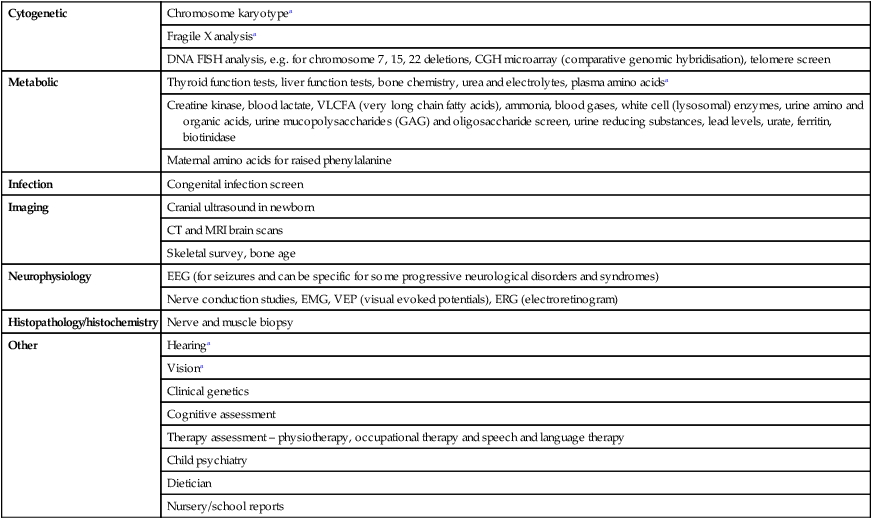

The choice of investigations to identify the cause is influenced by the child’s age, the history and clinical findings (Table 4.3). In some children, no cause can be identified even after extensive investigation.

Table 4.3

Investigations or assessment to consider for developmental delay

| Cytogenetic | Chromosome karyotypea |

| Fragile X analysisa | |

| DNA FISH analysis, e.g. for chromosome 7, 15, 22 deletions, CGH microarray (comparative genomic hybridisation), telomere screen | |

| Metabolic | Thyroid function tests, liver function tests, bone chemistry, urea and electrolytes, plasma amino acidsa |

| Creatine kinase, blood lactate, VLCFA (very long chain fatty acids), ammonia, blood gases, white cell (lysosomal) enzymes, urine amino and organic acids, urine mucopolysaccharides (GAG) and oligosaccharide screen, urine reducing substances, lead levels, urate, ferritin, biotinidase | |

| Maternal amino acids for raised phenylalanine | |

| Infection | Congenital infection screen |

| Imaging | Cranial ultrasound in newborn |

| CT and MRI brain scans | |

| Skeletal survey, bone age | |

| Neurophysiology | EEG (for seizures and can be specific for some progressive neurological disorders and syndromes) |

| Nerve conduction studies, EMG, VEP (visual evoked potentials), ERG (electroretinogram) | |

| Histopathology/histochemistry | Nerve and muscle biopsy |

| Other | Hearinga |

| Visiona | |

| Clinical genetics | |

| Cognitive assessment | |

| Therapy assessment – physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy | |

| Child psychiatry | |

| Dietician | |

| Nursery/school reports |

Developmental delay

Global developmental delay (also called early developmental impairment) implies delay in acquisition of all skill fields (gross motor, vision and fine motor, hearing and speech, and language and cognition, social/emotional and behaviour). It usually becomes apparent in the first 2 years of life. Global developmental delay is likely to be associated with cognitive difficulties, although these may only become apparent several years later. The presence of global developmental delay should always generate investigation into a possible cause such as those listed in Table 4.2. When children become older and the clinical picture is clearer, it is more appropriate to describe the individual difficulties such as learning disability, motor disorder and communication difficulty, rather than using the term global developmental delay.

Abnormal motor development

Causes of abnormal motor development include:

• central motor deficit e.g. cerebral palsy

• congenital myopathy/primary muscle disease

• spinal cord lesions, e.g. spina bifida

• global developmental delay, as in many syndromes or of unidentified cause.

Late walking (>18 months old) may be caused by any of the above but also needs to be differentiated from children who display the normal locomotor variants of bottom-shuffling or commando crawling (see Ch. 3), where walking occurs later than with crawlers.

Cerebral palsy (CP)

Clinical presentation

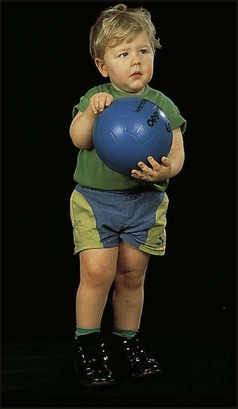

• Abnormal limb and/or trunk posture and tone in infancy with delayed motor milestones (Fig. 4.3); may be accompanied by slowing of head growth

• Feeding difficulties, with oromotor incoordination, slow feeding, gagging and vomiting

In CP, primitive reflexes, which facilitate the emergence of normal patterns of movement and which need to disappear for motor development to progress, may persist and become obligatory (see Ch. 3).

The diagnosis is made by clinical examination, with particular attention to assessment of posture and the pattern of tone in the limbs and trunk, hand function and gait. There are three main clinical subtypes: spastic (90%), dyskinetic (6%) and ataxic (4%). A mixed pattern may occur. Functional ability is described using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (Table 4.4).

Table 4.4

Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)

| Level I | Walks without limitations |

| Level II | Walks with limitations |

| Level III | Walks using a handheld mobility device |

| Level IV | Self-mobility with limitations; may use powered mobility |

| Level V | Transported in a manual wheelchair |

See http://www.canchild.ca/en/measures/gmfcs.asp for further details (accessed January 2011).

Spastic cerebral palsy

• Hemiplegia – unilateral involvement of the arm and leg (Fig. 4.4). The arm is usually affected more than the leg, with the face spared. Affected children often present at 4–12 months of age with fisting of the affected hand, a flexed arm, a pronated forearm, asymmetric reaching or hand function. Subsequently a tiptoe walk (toe–heel gait) on the affected side may become evident. Affected limbs may initially be flaccid and hypotonic, but increased tone soon emerges as the predominant sign. The past medical history may be normal, with an unremarkable birth history with no evidence of hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. In some, the condition is caused by neonatal stroke. Larger brain lesions (strokes) may cause a hemianopia (loss of half of visual field) of the same side as the affected limbs

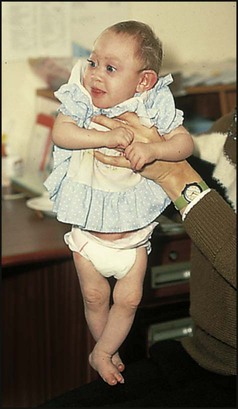

• Quadriplegia – all four limbs are affected, often severely. The trunk is involved with a tendency to opisothonus (extensor posturing), poor head control and low central tone (Fig. 4.5). This more severe cerebral palsy is often associated with seizures, microcephaly and moderate or severe intellectual impairment. There may have been a history of perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy.

• Diplegia – all four limbs, but the legs are affected to a much greater degree than the arms, so that hand function may appear to be relatively normal. Motor difficulties in the arms are most apparent with functional use of the hands. Walking is abnormal. Diplegia is one of the patterns associated with preterm birth due to periventricular brain damage.

Dyskinetic cerebral palsy

Abnormal speech and language development

Speech and language delay may be due to:

• difficulty in speech production from an anatomical deficit, e.g. cleft palate, or oromotor incoordination, e.g. cerebral palsy

• environmental deprivation/lack of opportunity for social interaction

Speech and language disorders include disorders of:

• language expression – inability or difficulty in producing speech whilst knowing what is needing to be said

• phonation and speech production such as stammering (dysfluency), dysarthria or verbal dyspraxia

• pragmatics (difference between sentence meaning and speaker’s meaning), construction of sentences, semantics, grammar

There are many tests of language development. These include:

Abnormal development of social/communication skills (autistic spectrum disorders)

Children who fail to acquire normal social and communication skills may have an autistic spectrum disorder. The prevalence of autistic spectrum disorder is 3–6/1000 live births. It is more common in boys. Presentation is usually between 2 and 4 years of age when language and social skills normally rapidly expand. The child presents with a triad of difficulties and associated co-morbidities (Box 4.1).

Specific learning difficulty

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) or dyspraxia

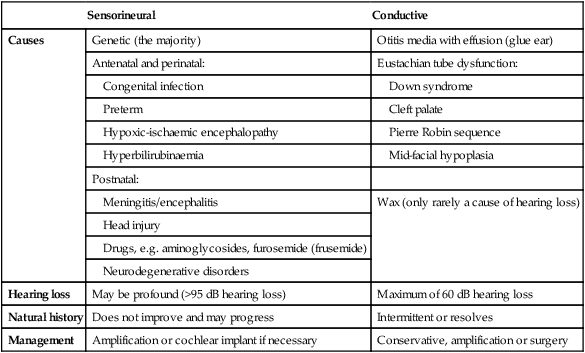

Hearing impairment

• sensorineural – caused by a lesion in the cochlea or auditory nerve and is usually present at birth

• conductive – from abnormalities of the ear canal or the middle ear, most often from otitis media with effusion.

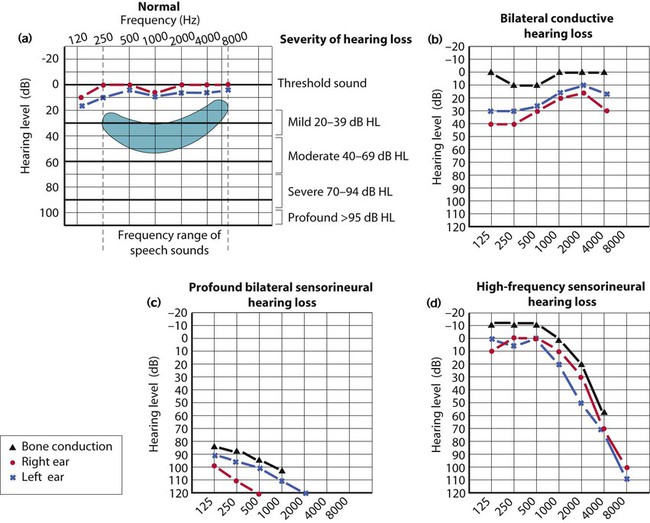

The causes, natural history and management of hearing loss are listed in Table 4.5. Hearing tests are described in Chapter 3. The typical audiogram in sensorineural and conductive hearing loss is shown in Figure 4.6.

Table 4.5

Causes and management of hearing loss

| Sensorineural | Conductive | |

| Causes | Genetic (the majority) | Otitis media with effusion (glue ear) |

| Antenatal and perinatal: | Eustachian tube dysfunction: | |

| Congenital infection | Down syndrome | |

| Preterm | Cleft palate | |

| Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy | Pierre Robin sequence | |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia | Mid-facial hypoplasia | |

| Postnatal: | ||

| Meningitis/encephalitis | Wax (only rarely a cause of hearing loss) | |

| Head injury | ||

| Drugs, e.g. aminoglycosides, furosemide (frusemide) | ||

| Neurodegenerative disorders | ||

| Hearing loss | May be profound (>95 dB hearing loss) | Maximum of 60 dB hearing loss |

| Natural history | Does not improve and may progress | Intermittent or resolves |

| Management | Amplification or cochlear implant if necessary | Conservative, amplification or surgery |

Sensorineural hearing loss

The child with severe bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment will need early amplification with hearing aids for optimal speech and language development. Hearing aid use requires close supervision, beginning in the home together with the parents and continuing into school. Children often resist wearing hearing aids because background noise can be amplified unpleasantly. Cochlear implants may be required where hearing aids give insufficient amplification (Fig. 4.7).

Abnormalities of vision

Normal visual development and tests of vision are described in Chapter 3.

Visual impairment may present in infancy with:

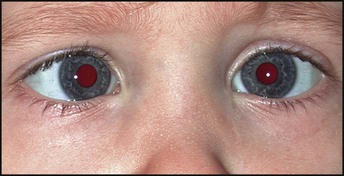

• loss of red reflex from a cataract

• a white reflex in the pupil, which may be due to retinoblastoma, cataract or retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

• not smiling responsively by 6 weeks post-term

Squint (strabismus)

Squints are commonly divided into:

• Concomitant (non-paralytic, common) – usually due to a refractive error in one or both eyes, which is often treated by correction with glasses but may require surgery. These squints are particularly common in children with neurodevelopmental delay. The squinting eye most often turns inwards (convergent), but there can be outward (divergent) or, rarely, vertical deviation.

• Paralytic (rare) – varies with gaze direction due to paralysis of the motor nerves. This can be sinister because of the possibility of an underlying space-occupying lesion such as a brain tumour.

Corneal light reflex test

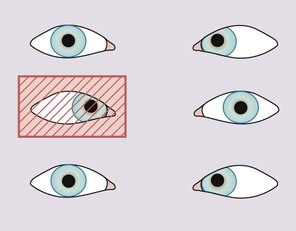

For the non-specialist, the light reflex test is used to detect squints (Fig. 4.8). It is easiest to use a pen-torch held at a distance to produce reflections on both corneas simultaneously. The light reflection should appear in the same position in the two pupils. If it does not, a squint is present. However, a minor squint may be difficult to detect.

Cover test

When a squint is present and the fixing eye is covered, the squinting eye moves to take up fixation (Fig. 4.9). The child’s interest can be attracted with a toy or light. The test should be performed with the object near (33 cm) and distant (at least 6 m), as certain squints are present only at one distance. Occlusion should be with a card or plastic occluder. These tests are difficult to perform and reliable results are best obtained by an orthoptist or ophthalmologist.

Severe visual impairment

This affects 1 in 1000 live births in the UK but is higher in developing countries. A family history of severe visual impairment, developmental delay or extreme prematurity places the infant at an increased risk. The main causes are listed in Box 4.2. In developed countries, about 50% of severe visual impairment is genetic; in developing countries acquired causes such as infection are more prevalent. When visual impairment is of cortical origin, resulting from cerebral damage, examination of the eye, including the pupillary responses, may be normal.

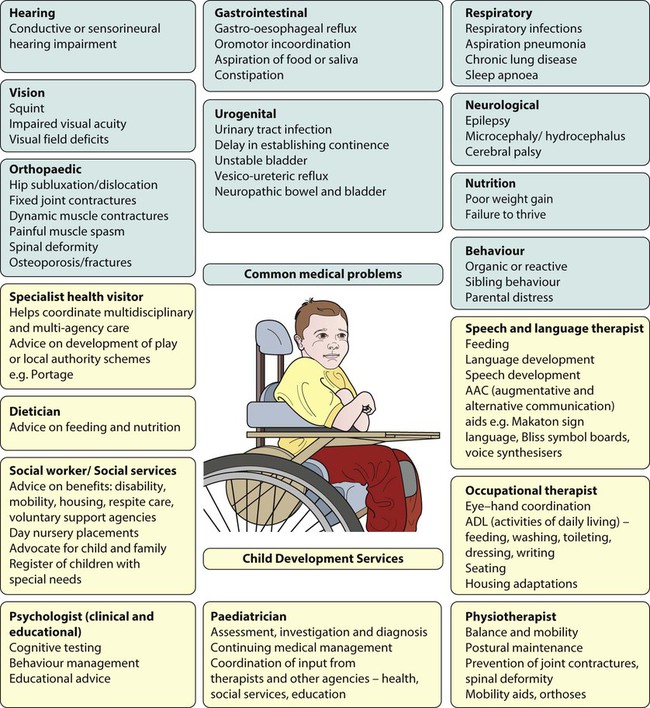

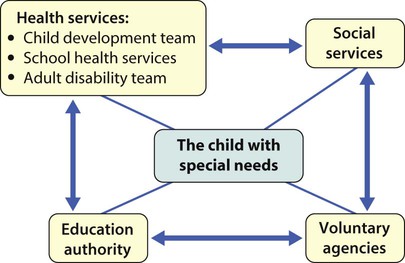

Multidisciplinary child development services

A child development service (CDS):

• is multidisciplinary with predominantly health professionals (paediatrician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, clinical psychologist, specialist health visitor, dietician) in the team but often also includes a social worker (Fig. 4.10)

• is multi-agency (Fig. 4.11) and may include health, social services, education, volunteers, voluntary agencies, parent support groups

• aims to provide a coordinated service with good inter-agency liaison to meet the functional needs of the child

• predominantly sees preschool children with moderate or severe difficulties but may have resources to support children with milder problems

• may provide multidisciplinary support and monitor children up to school-leaving age (16–19 years)

• maintains a register of children with disabilities and special needs (this may be held by Social Services, but there is an increasing trend to single multi-agency Special Needs registers)

• is community or hospital based but has emphasis on children’s needs within the community (home, nursery, school), regardless of its location

• often has a nominated key worker for a child, to facilitate parents getting access to information and services their child may need.

• assessment of functional skills

• a coordinated approach to care (multidisciplinary, multi-agency).

Functional skills kept under review include:

• speech, language and communication, including social/communication skills

• behaviour, social and emotional skills

Many children with special needs have medical problems (Fig. 4.10) which require investigation, treatment and review. Good inter-professional communication is vital for well-coordinated care. This is assisted by all professionals keeping entries in the child’s personal child health record up to date.

• Rehabilitation following acquired brain injury

• Surgery for cerebral palsy, scoliosis

• Spasticity management, including botulinum toxin injections to muscles

• Epilepsy unresponsive to two or more anticonvulsants or where there is severe cognitive and behavioural regression related to epilepsy

• Complex communication disorders, diagnosis and therapeutic intervention

• Mixed complex learning problems, often with neuropsychiatric co-morbid symptoms

• Provision of communication aids (Fig. 4.12).

• Sensory impairments, e.g. cochlear implants

• Services for severe visual and hearing impairment

• Specialised seating/wheelchairs and orthoses (Fig. 4.13).

• Management of movement disorders, e.g. continuous infusion of intrathecal baclofen and deep brain stimulation to basal ganglia.

The rights of disabled children

Irrespective of their disability, the aspirations and rights of children, as affirmed by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, need to be respected (see Ch. 1). Technological advances to improve mobility, communication and emotional expression are helping enable people with disability to better achieve their full potential, rather than being held back by their disability. However, this requires skilled assistance and adequate resources. Prominent public figures who function effectively despite disabilities help to make the public appreciate what can be achieved and serve as an inspiration to those with disabilities. The World Health Organization’s model of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) stresses the important outcomes of activity and participation. Any interventions for people with disability either on an individual level or in society as a whole should aim to improve these outcomes.