Chapter 14 Developmental-Behavioral Screening and Surveillance

Of children with measurable delays or disabilities, the most common (and least well-identified) condition is speech-language impairment (17.5% at 30-36 mo) (Chapter 32), Other common conditions are social-emotional disorders (9.5-14.2%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (7.8%) (Chapter 30), learning disabilities (6.5%), intellectual disabilities (1.2%) (Chapter 33), and autism spectrum disorders (0.6-1.1%) (Chapter 28). Less common conditions include cerebral palsy (physical impairments) (0.23%) (Chapter 591.1), hearing impairment (0.12%), vision impairment (0.8%) (Chapter 613), and other forms of health or physical impairments (e.g., Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, traumatic brain injury). Early detection of emerging deficits among very young children typically requires clinicians to screen with tools proven to be accurate.

Early Detection in Primary Care

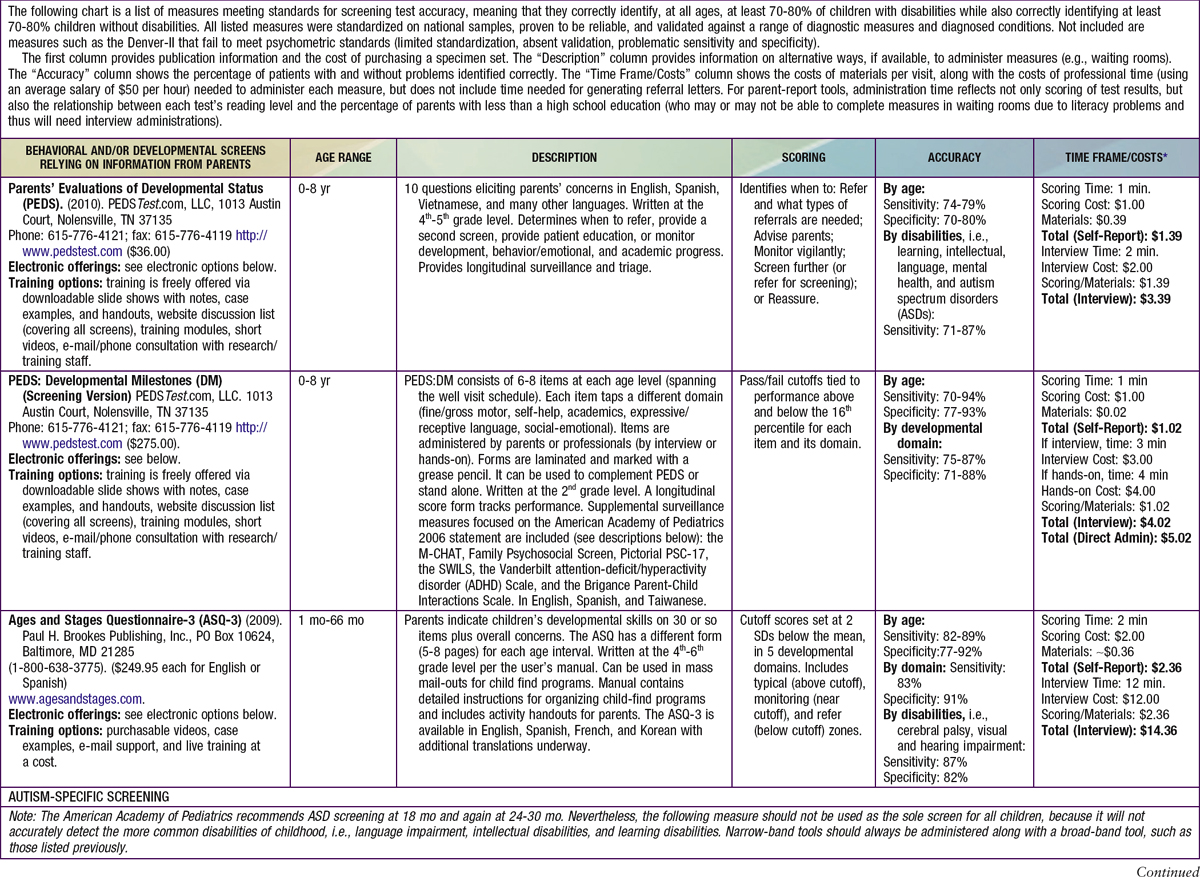

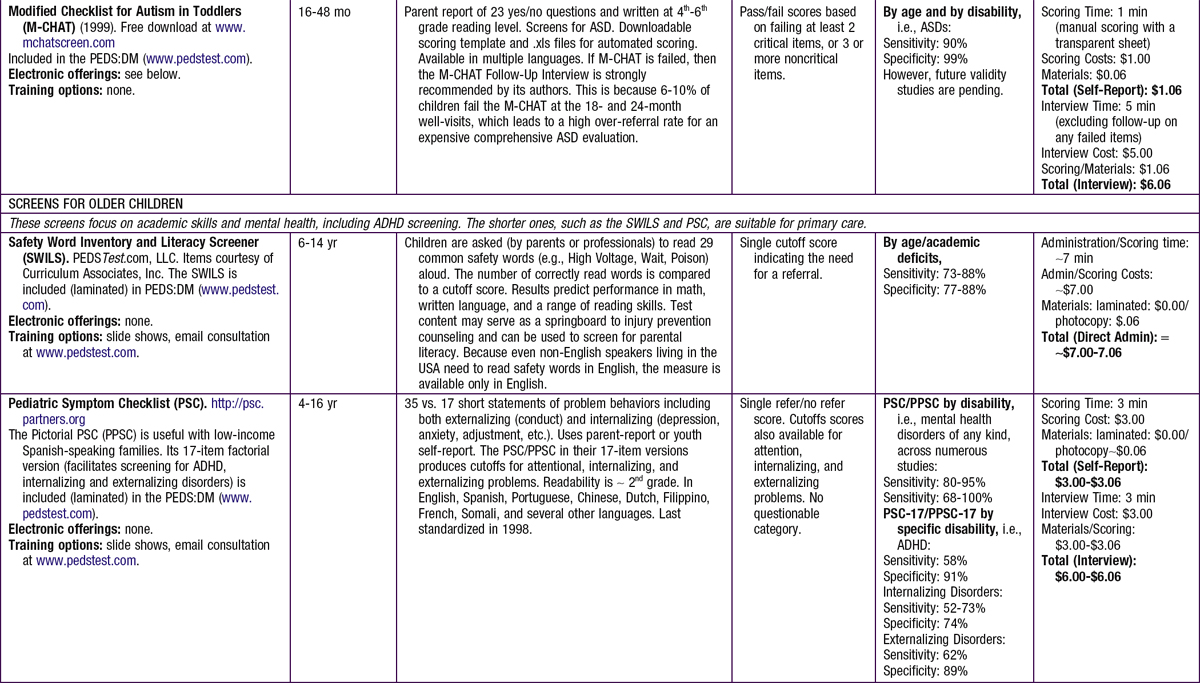

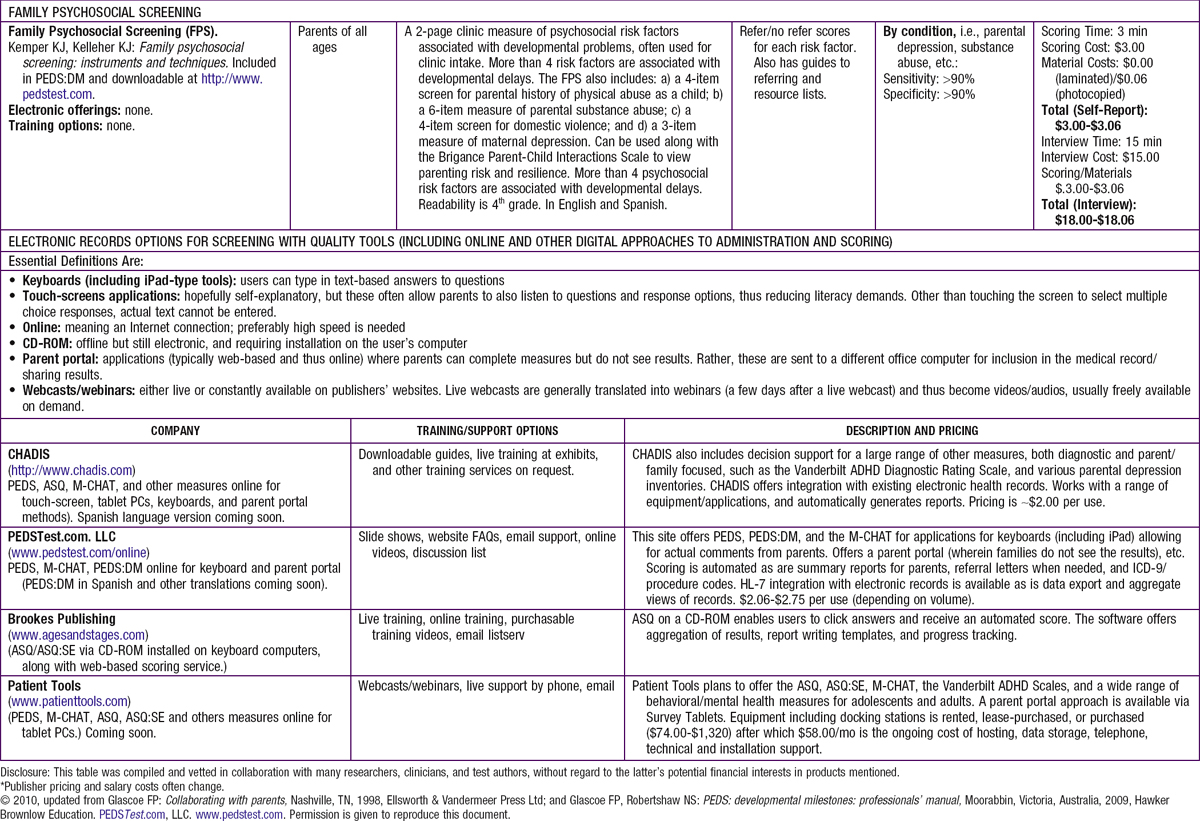

Screening and surveillance must use quality measures to ensure accurate detection. Fortunately, many tools serve both functions. Table 14-1 shows a range of screens useful for early detection of developmental and behavioral problems including autism spectrum disorders. Because well visits are brief and have enormous agendas (physical exams, immunizations, anticipatory guidance, safety and injury prevention counseling, and developmental promotion), tools relying on information from parents are ideal because they can be completed in advance of appointments, online, or in waiting or exam rooms.

Table 14-2 provides a step-by-step process of evidence-based screening and surveillance. The sequence is based on the American Academy of Pediatrics 2006 policy statement (with enhancements added to the referral and follow-up process).

Table 14-2 COMBINING SCREENING AND SURVEILLANCE: A PRACTICE ALGORITHM

1. ENSURE A MEDICAL HOME.

Timely, equitable access to care logically correlates to well child care compliance rates and therefore, developmental delay identification rates. Children with developmental and behavioral problems or special health care needs use health care services at >2× the rate of other patients. Visits are often complex due to the need to make referrals, locate information from prior visits and services, make follow-up appointments, and coordi nate with other providers. The AAP’s medical home model (www.medicalhomeinfo.org) is an essential guide to organizing practices to ensure continuity and coordination of care and to best meet the needs of children with disabilities and their families.

2. REVIEW MEDICAL CHART FOR HEALTH RISK FACTORS.

Consider potentially harmful exposures including radiation or medications, infectious illnesses, fever, addictive substances, trauma, and results of neonatal screens, including phenylketonuria, congenital hypothyroidism, and numerous other metabolic conditions. The perinatal history includes birthweight, gestational age, Apgar scores, and any medical complications (Chapter 88.1). Postnatal medical factors that are sometimes overlooked include failure to thrive, abnormal growth curves for head circumference, neurological (e.g., seizure) disorders, endocrine disorders, amblyopia or other significant forms of visual impairment, chronic respiratory or allergic illness, conductive or sensorineural hearing impairment, congenital heart disease, iron deficiency anemia, head trauma, and sleep disorders (particularly obstructive sleep apnea [Chapter 17]). In most states, children are automatically eligible for early intervention if their conditions have a well-established association with developmental delay (e.g., Down syndrome, birthweight <1500 g).

3. IDENTIFY AND MONITOR PSYCHOSOCIAL RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS.

Risk factors include parents with less than a high school education, parental mental health or substance abuse problems, 4 or more children in the home, single parent, poverty, frequent household moves, limited social support, parental history of abuse as a child, ethnic minority, and problematic parenting style. The latter is often observable during encounters (e.g., parents who don’t talk much to their children, tend to bark orders at them, talk to their children only when they are crying, etc.). Four or more risk factors tend to plunge developmental status into the below average range and suggest the need for enrichment or remedial programs such as Head Start/Early Head Start regardless of screening results. All children with a history of abuse or neglect should be referred automatically for early intervention. An initial visit standardized intake measure, such as the Family Psychosocial Screen (see Table 14-1), followed by readministration of its 2-item parental depression screen and any other of its imbedded measures (e.g., substance abuse, housing and food instability) in the 2nd year of life. When a concerning psychosocial screen occurs, the next step is to provide an appropriate community referral (e.g., mental health provider, domestic violence shelter, parenting or postpartum depression support group) and to contact (via a phone call or a courtesy copy note) the parent’s primary care provider. If parental suicidal/homicidal ideation or psychosis is identified, consider that a medical emergency. Not only does psychosocial screening allow for higher quality surveillance, it’s an early opportunity to ameliorate or prevent a future delay.

Protective (also called resilience) factors focus almost exclusively on positive parenting styles. These behaviors are often observable (e.g., when parents actively and age-appropriately teach children new things, label objects of interest, share books, and converse with their child [including back-and-forth sound play in infancy, playing peek-a-boo, etc.]). Identifying other positive parenting behaviors usually requires questioning (e.g., whether parents talk with children at meals and perceive their child as soothable and interested in conversing). PEDS:DM (described in Table 14-1) includes a validated parent-child interactions questionnaire. Trigger questions from the Bright Futures initiative are also helpful (http://www.brightfutures.org).

4. ELICIT AND ADDRESS PARENTS’ CONCERNS.

Informal questions to parents are rarely effective at eliciting developmental-behavioral concerns. In addition, informal questions do not render the decision support providers need in order to recognize what type of intervention is needed. It is best to use a standardized, validated tool such as PEDS that not only offers questions proven to enhance parent-professional communication, but also an evidence-based algorithm for helping professionals determine when to refer, advise, monitor more carefully, screen further, or reassure. PEDS also functions as both a screening and surveillance measure.

5. ADMINISTER AND SCORE DEVELOPMENTAL-BEHAVIORAL SCREENING TEST(S) FOCUSED ON MILESTONES.

Because surveillance requires monitoring milestones, and because the AAP recommends formal screening at specific visits, both screening and surveillance can be accomplished simultaneously via measures such as PEDS:DM or Ages and Stages Questionnaire (see Table 14-1). These measures offer longitudinal progress tracking and evidence-based cutoff scores. Such screens are needed at 9, 18, 24-30 months and at annual well visits thereafter. An autism-specific screen should be added at 18 months and again at 24 months (e.g., M-CHAT [Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers]). Use of previsit, parent-completed tools is particularly efficient. When a parent-report screen is completed and scored before the visit, clinicians are better able to collaborate with families during encounters, determine the optimal content for developmental promotion, refine the physical exam (and any subsequent subspecialty referrals), and incorporate information about psychosocial risk and resilience factors into quality decision-making about needed intervention services. Administration options may include online parent portals, paper/pencil in waiting rooms, and interview at weigh-in or by nursing staff.

6. IF INDICATED, ADMINISTER (OR REFER FOR) ADDITIONAL MENTAL HEALTH SCREENS.

Whenever a child performs poorly on broad-band screens or when parents’ concerns about behavior or social-emotional concerns persist, the AAP recommends use of focused measures of mental health (meaning social-emotional and behavioral issues). The overlap between developmental and mental health problems is considerable; about 1 in 3 children with developmental problems also have emotional difficulties. PEDS and the PEDS:DM provide brief indicators, but more in-depth measures such as the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social-Emotional are helpful. See www.aap.org/mentalhealth for more information and additional tool options. When time is limited, parents can be given measures to take home in preparation for a follow-up appointment. Alternatively, referrals for mental health screening can be made to services funded by the IDEA including early intervention and public schools special education (see Resources for Screening, Nonmedical Referral, and Developmental Promotion). Such programs are prepared to administer mental health screens and other detailed assessments without charge to families.

7. PROVIDE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION AND CLINICAL OBSERVATION.

Points of particular importance include growth parameters and head shape and circumference, facial and other body dysmorphology, eye findings (e.g., cataracts in various inborn errors of metabolism), vascular markings, and signs of neurocutaneous disorders (café-au-lait spots in neurofibromatosis, hypopigmented macules in tuberous sclerosis). Vision and hearing screening should occur per the AAP’s guidelines. Examine closely for findings consistent with abuse/neglect (e.g., geometrically shaped bruises). A neurological exam (Chapter 584), along with careful observation of the child’s behavior and the parent-child interaction, is a key part to any developmental evaluation. Does the parent interact appropriately with the child or does something “not feel right” during your exam? Does the child behave age-appropriately around the parent? Is there a concern about the child being over or under attached to the parent? (See Step 3.)

8. WHEN INDICATED, PLAN AND REFER FOR ADDITIONAL MEDICAL TESTS.

Vision and hearing screening are needed, not only routinely but additionally when developmental-behavioral screening tests indicate probable problems. Many IDEA services cannot begin testing unless these are documented in referral letters. With young children, referrals to audiologists may be needed (depending on office equipment and child compliance). Iron deficiency and lead poisoning are common contributors to developmental delays and are easily detected through screening. Electroencephalograms and neuroimaging are not routinely indicated but might be used if there is clinical suspicion of a seizure disorder, hydrocephalus, micro- or macrocephaly, encephalopathy, neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, brain tumor, or other neurological problem (not including autism). Extreme handedness at an early age and persistence of fisting after 4 months is another indicator of potential neuron migration disorders requiring imaging. Uncommonly, surveillance may indicate a need for additional metabolic screens, such as serum electrolytes and glucose, venous blood gas, serum ammonia, urine glycosaminoglycans, endocrine screens (e.g., TSH, free T4), genetic testing (chromosomal analysis, DNA for fragile X, etc.), or screens for an infectious disease (e.g., HIV antibody testing [Chapter 268], TORCH infection testing [Chapter 103]). Due to the need to discern which tests are needed, referral to a developmental-behavioral or neurodevelopmental pediatrician is wise.

9. EXPLAIN SCREENING RESULTS TO PARENTS.

The primary medical provider should present the screening results to parents in person. Results should be explained in a positive manner (e.g., “There is much we can do to help.”) with emphasis on available community services and how these optimize a child’s (and family’s) outcome. Providers’ first-hand experience with community services is essential for understanding what intervention programs do and for adequately describing them to families. It is advisable to use euphemistic terms for diagnosis, because the specific condition may not be known (e.g., “developmental delay,” “behind other children,” “seems to be having difficulties with….”), and because determining a final diagnosis is not needed for enrollment in intervention. Asking the parents if they know any families with children who have developmental differences may be helpful in understanding any strong reaction to the information being presented. Offers to re-explain findings to other family members may be needed.

10. MAKE REFERRALS FOR NONMEDICAL INTERVENTIONS AND FOLLOWING UP.

Making appointments for families, wherever possible, increases the likelihood of follow through. Referrals should always start with IDEA programs (www.nectac.org). Services are free to parents, provided under federal and state law within 30-40 school days from the time of referral, and generally provide high quality therapies, evaluations, remediation programs or high quality preschool for those with psychosocial risk factors (or when further evaluation reveals the screening results were false-positive). Referral forms or letters, which target the areas of concern, help IDEA programs to better assess and track children. To expedite assessments and eligibility placements, parental signatures should be obtained to release information back and forth between the medical provider and the IDEA program. Some children will be automatically eligible for services based on a condition highly likely to result in a developmental delay (e.g., Down syndrome, birth weight <1500 g). Referral forms or letters should include suggestions for the types of evaluations needed (e.g., speech-language therapy, occupational and physical therapy, social-emotional assessment, intelligence testing, academics) and documentation of hearing and vision status, because IDEA programs require this information before providing evaluations. If referrals seem needed for autism-specific evaluations or mental health services, refer for these separately but do not defer referrals to IDEA services in the interim. Many specialized evaluations and interventions have lengthy waiting lists (e.g., 9-12 months). Children need prompt services through IDEA while they wait.

11. REVIEW REPORTS AND OTHER FEEDBACK FROM REFERRAL SOURCES AND FOLLOW UP WITH FAMILIES.

Surveillance does not end after a referral. Not all families follow through with clinicians’ recommendations for services. Some parents wish to try at-home interventions. Other parents get “cold feet” and may be deterred by differing opinions from relatives and spouses (e.g., “His father was just like that”; “It is a phase. She’ll grow out of it.”). A follow-up appointment in 3-4 months is helpful for encouraging families, and, if needed, at least advising parents to visit the programs recommended. Reassessing parents’ concerns is also helpful because when parents have multiple concerns, they are more likely to seek intervention programs. Note that ambiguous concerns such as “I think he’s doing better” still convey substantial risk.

When families have followed through with recommendations, clinicians should carefully review (and, when indicated, take action on) reports from the IDEA programs and other subspecialists. These reports may include recommendations for specific services (e.g., speech-language, occupational or physical therapy), and some states require physician authorization. IDEA programs should ideally give feedback to clinicians about whether the child followed up on the referral (hence the value of a two-way consent form). Was the child lost to follow-up, screened out, placed on a monitoring list, or made eligible for services? When children have not qualified for services, providers should make referrals to Head Start, quality daycare/preschool or parent training (and establish a vigilant plan for rescreening because, if delays persist, children may qualify for IDEA programs in the future). Clinicians should also establish communication preferences with intervention programs (e.g., by email, fax, or telephone [including available hours]) and the preferences for the kind of information to be sent (e.g., evaluation reports, individual education plans, etc.).

12. PROVIDE DEVELOPMENTAL-BEHAVIORAL PROMOTION.

When screening and surveillance methods do not identify a need for nonmedical interventions, the need to address “the normal problems of normal children” remains. All parents need advice about typical problems (e.g., toilet training, temper tantrums). All parents need to be encouraged to promote their child’s language and preacademic/academic development. This is most easily accomplished with written patient education materials, by encouraging parents to visit websites with quality information, participating in Reach and Read, or by parent training classes, group well visits, or social work services. A well-organized system for filing and retrieving parent-focused materials is essential (see Table 15-2). Follow up with families, in 6-8 weeks to assess the effectiveness of promotion activities, especially in-office advice about behavior and social skills. If less than successful, encourage parents to engage in more intensive services (e.g., parenting classes, family therapy). Information and referral resources are listed under Resources for Screening, Nonmedical Referral, and Developmental Promotion.

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; PEDS:DM, Parents’ Evaluations of Developmental Status: Developmental Milestones.

Resources for Screening, Nonmedical Referral, and Developmental Promotion

American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-420.

American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health. Enhancing pediatric mental health care: strategies for preparing a primary care practice. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 3):S87-S108.

Bailey DB, Hebbeler K, Scarborough A, et al. First experiences with early intervention: a national perspective. Pediatrics. 2004;114:887-896.

Bailey DB, Skinner D, Warren SF. Newborn screening for developmental disabilities: reframing presumptive benefit. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:1889-1893.

Blair M, Hall D. From health surveillance to health promotion: the changing focus in preventive children’s services. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:730-735.

Glascoe FP. Are over-referrals on developmental screening tests really a problem? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:54-59.

Glascoe FP. Toward a model for an evidenced-based approach to developmental/behavioral surveillance, promotion and patient education. Ambul Child Health. 1999;5:197-208.

Glascoe FP, Leew S. Parenting behaviors, perceptions and psychosocial risk: impact on child development. Pediatrics. 2010;125:313-319.

Glascoe FP, Oberklaid F, Dworkin PH, et al. Brief approaches to educating parents and patients in primary care. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E10.

Hix-Small H, Marks K, Squires J, et al. Impact of implementing developmental screening at 12 and 24 months in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2007;120:381-389.

Magar NA, Dabova-Missova S, Gjerdingen DK. Effectiveness of targeted anticipatory guidance during well-child visits: a pilot trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:450-458.

Johnson CP, Myers SC, Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-1215.

Marks K, Hix-Small H, Clark K, et al. Lowering developmental screening thresholds and raising quality improvement for preterm children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1516-1523.

Newacheck PW, Strickland B, Shonkoff JP, et al. An epidemiologic profile of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:117-123.

Pinto-Martin JA, Dunkle M, Earls M, et al. Developmental stages of developmental screening: steps to implementation of a successful program. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1928-1932.

Prelock PA, Hutchins T, Glascoe FP. Speech-language impairment: how to identify the most common and least diagnosed disability of childhood. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:136.

Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Ou S-R, et al. A 19-year follow-up of low-income families: effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:730-739.

Rosenberg SA, Zhang D, Robinson CC. Services for young children: prevalence of developmental delays and participation in early intervention. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1503-e1509.

Schonwald A, Huntington N, Chan E, et al. Routine developmental screening implemented in urban primary care settings: more evidence of feasibility and effectiveness. Pediatrics. 2009;123:660-668.

Sices L. How do primary care physicians manage children with possible developmental delays? Pediatrics. 2004;113:274-282.

Sices L, Drotar D, Keilman A, et al. Communication about child development during well-child visits: impact of Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status Screener with or without an informational video. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1091-e1099.

Wang L, Leslie DL. Health care expenditures for children with autism spectrum disorders on Medicaid. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psych. 2010;49:1165-1171.

Zuckerman B. Promoting early literacy in pediatric practice: twenty years of Reach Out and Read. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1660-1665.