12.1 Dermatology

Introduction

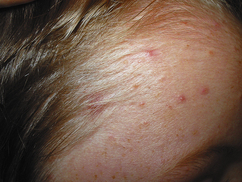

For children who present to the ED with the primary symptom in another organ, the physician has an opportunity to observe cutaneous signs of disease, which may be relevant or may be coincidental to the child’s presentation, for example, a 5-year-old boy (Fig. 12.1.1) who presents with gastroenteritis. You notice the mild comedonal rash on his forehead and recognise that this is unusual at this age. Examination shows that he is tall for his age and has inappropriate penile (but not testicular) growth. His hyperadrenergic state can be investigated and treated years before it might otherwise have been recognised.

Erythroderma and skin failure

Management

Vesiculobullous rashes

Varicella (chickenpox)

Management

Management

Herpes simplex infection (HSV)

Management

Management consists of the following;

Recurrent cutaneous herpes simplex can occur weeks or months after the primary episode. Recurrences usually get milder and less common with time but exacerbations can occur throughout childhood and later life (Fig. 12.1.2). Recurrences can lead to significant time off school. Antiviral prophylaxis may reduce the frequency and severity of recurrences, and should be used if recurrences are frequent or debilitating.

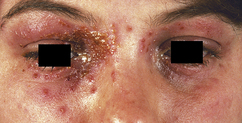

Eczema herpeticum

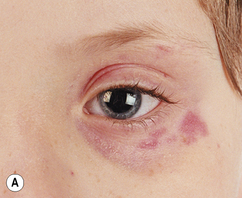

Herpes simplex infection in children with eczema is quite common. It occurs in children with any severity of eczema including children with mild eczema under excellent control. Many cases are misdiagnosed either as an exacerbation of the eczema or as bacterial infection (Fig. 12.1.3). Grouped vesicles may be prominent, but more often vesicles are rudimentary or absent and the infection may present as a group of shallow 2–4 mm monomorphic erosions on an inflamed base. In more severe cases, evolution is rapid and large crops of vesicles can arise daily. Ulcers may coalesce into larger erosions with scalloped edges. The infected area may not be painful or itchy.

Fig. 12.1.3 Eczema herpeticum. Typical monomorphic vesicles can be seen away from the central weeping area.

Management

Impetigo (school sores)

This is caused by Staphylococcus aureus or group A Streptococcus or both.

Bullous impetigo is due to Staphylococcus aureus and presents as flaccid blisters on normal skin. Lesions are rounded and well demarcated and may be single, grouped or widespread. Their onset and spread may be rapid or occur over days. New blisters appear and existing blisters rupture to give shallow moist erosions that can be many centimetres in size. There is often loose epithelium and/or brown crusting peripherally and some degree of central healing (Fig. 12.1.4). In more chronic cases, lesions may appear annular.

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis may occur in the ensuing 2 months. Contrary to long-held beliefs, it now seems likely that chronic streptococcal impetigo may also be a precursor of rheumatic heart disease in communities where medical conditions are poor and skin hygiene is suboptimal.1

Management

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Management

Erythema multiforme

This is a specific hypersensitivity syndrome that occurs at any age, often preceded by facial herpes simplex virus infection. It is over-diagnosed in emergency departments. Most children diagnosed with erythema multiforme actually have urticaria, often with large lesions with annular or polycyclic borders. In erythema multiforme, the primary lesions are red papules, usually symmetrical and involving the forearms, palms, feet, face, neck and trunk. They can be found anywhere. There may be few or many lesions. At least some of the papules will form classical target lesions – these have an inner zone of epidermal injury (purpura, necrosis or vesicle), an outer zone of erythema and sometimes a middle zone of pale oedema (Fig. 12.1.5). These papules and target lesions are not migratory. The involvement of mucous membranes is common but unlike Stevens–Johnson syndrome, is limited to isolated patches. Most cases are caused by herpes simplex virus, including most of the cases that occur without prior symptoms. Drugs are an uncommon cause. Erythema multiforme does not evolve into Stevens–Johnson syndrome. They are different conditions.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis

Management

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Recurrence some years after successful treatment has been reported.

Management

Sunburn and photosensitivity

Management

Primary photosensitivity disorders

Porphyrias and other inherited disorders with photosensitivity

Photosensitivity and bullous reactions to drugs

Isolated blisters

For a child who presents with a single blister or a few blisters as an isolated finding, consider:

Chronic erosions or ulcers

Neonatal vesicles

Non-infective causes of neonatal vesicles include:

Pustular rashes

Acne

Acne mainly affects the forehead and face but can involve other sebaceous gland areas (neck, shoulders and upper trunk). Early lesions include blackheads, whiteheads and papules. In more severe cases there may be pustules or inflammatory cysts that can lead to permanent scarring. Acne is common in adolescence. It is treatable and no person with acne should be told it is an inevitable part of adolescence. Several topical and oral acne therapies are available and should be used to treat the disease. Under-treated acne is a major medical cause of significant morbidity in adolescents and has a recognised mortality as a factor in teenage suicide. It can also lead to permanent scarring in 10% of untreated cases (Fig. 12.1.6). Significant acne in an adolescent attending the ED for another reason should not be ignored. The adolescent should be offered information, initial treatment and referral for ongoing management.

Management

Early onset acne

If comedones or acneiform papules are noted before puberty (see Fig. 12.1.1), you should consider the possibility of pathological androgen secretion (see below). Look for increased growth, genital development and advanced radiological bone age.

Atypical acneiform rashes

Pustular psoriasis

Psoriasis can present with pustules on an erythematous background. The pustules are sterile. The affected area may be limited to fingers, palms and soles, or local areas of skin, often with an annular arrangement of pustules. Alternatively, there may be erythroderma, high fever, malaise and arthralgias with widespread pustules coalescing into sheets of pus. Local pustular psoriasis can be treated topically (see psoriasis, p. 295). Generalised pustular psoriasis requires admission to hospital, rest, skin emollients and/or wet dressings, monitoring of fluid balance, electrolytes, renal and cardiac function and oral therapy (see erythroderma p. 281 and psoriasis p. 295).

Neonatal pustules

Papular (raised) rashes

Scabies

Not all itchy parasitic rashes are scabies. Many species of parasite can cause small itchy papules on the skin, in some cases hundreds of lesions. Bird mites, fleas, body lice, mosquitoes, sand flies, horse flies, bed bugs, ticks, chiggers, midges and harvest mites can all masquerade as scabies. Parasites can be collected from the skin on transparent adhesive tape. The CSIRO Australian National Insect Collection provides an identification service on http://www.csiro.au/services/InsectID.html.

Management

Papular acrodermatitis of childhood

Papular acrodermatitis of childhood is characterised by the acute onset of monomorphic, red or skin-coloured papules mainly on the limbs, buttocks and face, with striking sparing of the trunk (Fig. 12.1.7). In any given patient, the papules tend to all look the same, typically firm and dome shaped, measuring 2–4 mm in diameter. However, in different patients, the papules can vary from tiny, skin-coloured papules to larger urticarial plaques. Lesions may coalesce into patches on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees. Lesions may be papulovesicular (particularly on the limbs) or purpuric (particularly on the face). Hundreds of lesions may appear over several days. It is usually asymptomatic but may be itchy. Complete resolution occurs in 4–8 weeks.

Papular urticaria

Management

Molluscum

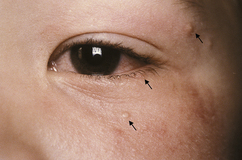

Molluscum may occur on the eyelid margin or adjacent area. This can cause a persistent unilateral conjunctivitis. The molluscum may be isolated and subtle and go unnoticed for months during which the child may receive multiple courses of antibiotic treatment for conjunctivitis (Fig. 12.1.8).

Management

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Red scaly rashes

Redness and scale indicate a combination of vasodilatation and epidermal involvement. Atopic eczema is the commonest cause of red scaly rashes in children (see p. 297). Other red scaly eruptions include seborrhoeic dermatitis (infants), psoriasis, tinea corporis, pityriasis rosea and pityriasis versicolor. If itch is present, consider any of the causes of eczematous rashes (p. 297).

Psoriasis

Minor nail pitting is often seen in childhood psoriasis.

Management

Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis (often called ringworm) is a common skin disorder, especially among children, but it may occur in people of all ages. It is caused by mould-like fungi (dermatophytes). Tinea infections can be transmitted by direct contact with affected individuals or by contact with contaminated items such as combs, clothing, shower, or pool surfaces. They can also be transmitted by contact with pets that carry the fungus (cats are common carriers). The typical lesion is a slow-growing erythematous ring with a clear or scaly centre. Scale is usually most prominent on the outside of the annular ring. However, tinea corporis can present in a wide variety of ways. It can be pustular or vesicular, particularly on the soles (Fig. 12.1.9), or it can spread to many sites within days. Between the toes, it presents as an itchy, white, scaly and macerated rash. Previous treatment with steroid ointments often leads to partial improvement in symptoms but causes spreading of the rash, the development of papules and the masking of diagnostic features. Tinea should be considered in any red, scaly rash where the diagnosis is unclear, particularly if there is a gradually spreading eruption with inflammatory edges.

Fig. 12.1.9 Inflammatory bullous fungal infection. (A) The foot with (B) secondary id reaction involving the hands.

Management

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

The term ‘seborrhoeic dermatitis’ has been used to describe a number of different clinical entities. It is most widely used for a particular dermatitis that occurs in areas of skin that have a high density of sebaceous glands, namely the scalp, the central ‘T-zone’ of the face, and the upper chest and back (not the anogenital area, see p. 316). It is due to a reaction to a Pityrosporum yeast, which is part of the normal flora at these sites.

Management

Eczematous rashes

Atopic eczema – general management principles

Atopic eczema – admission to hospital

Atopic eczema – use of topical steroid preparations

Always ask parents if they are treating their children with herbal creams. Any herbal cream that gives dramatic clearing should be assumed to contain corticosteroid products until proven otherwise. A British study in 2003 looked at a number of herbal creams given to children for eczema.3 Over 80% of those tested had illegal potent or very potent corticosteroid additives. Similar results have been found in previous studies.

Atopic eczema – facial

Some infants will present with facial lesions. There may or may not be eczema elsewhere. Facial eczema may be secondarily infected with Staphylococcus aureus, resulting in weeping and crusting (Fig. 12.1.10). Saliva is often a significant exacerbating factor. Herpes simplex virus infection needs to be considered (look for the typical monomorphic erosions, see p. 284). Treat with ointment moisturiser several times daily and, if indicated, oral cefalexin 30 mg kg−1 (max 500 mg) three times daily for 1 week. If appropriate follow up can be assured, use methyl-prednisolone 0.1% ointment for a few days to gain rapid control of the skin. Arrange follow up within a week to avoid problems from prolonged steroid use. Avoidance of irritating factors such as using napkin wipes on the face and general management measures are required to prevent relapse.

Atopic eczema with systemic associations

Eczematous skin lesions can also be associated with:

Allergic contact dermatitis – ‘black henna’ reactions

Treat with ointment moisturiser and potent topical corticosteroid or oral prednisolone if warranted.