122 Dermatologic Morphology

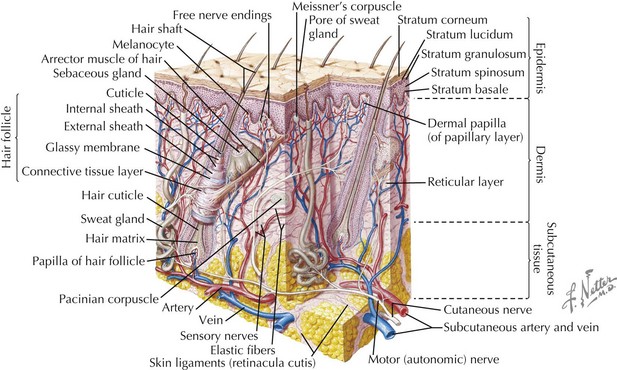

Basic Structure Of The Skin

The skin has three basic layers: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 122-1). Throughout these layers are additional structures and appendages that contribute to the skin’s functionality.

Approach To Dermatologic Morphology And Disease

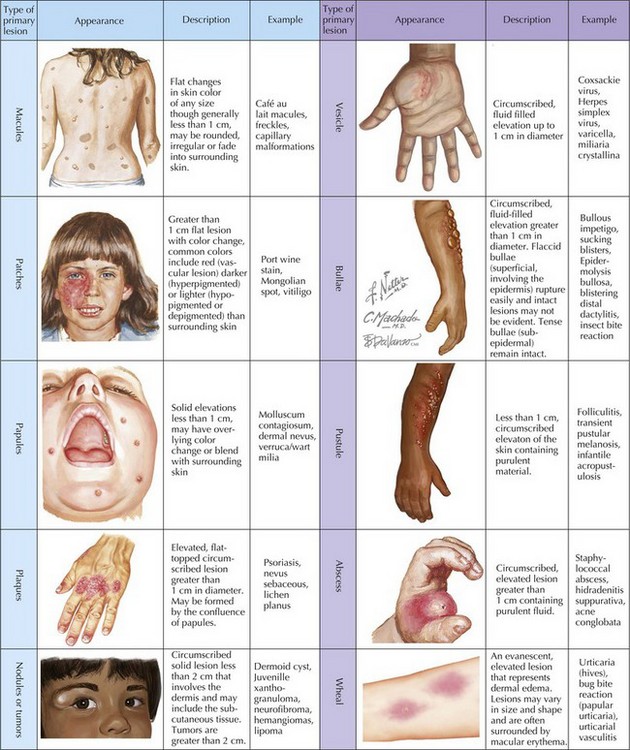

Primary Lesions

Primary lesions (Figure 122-2) are characterized by their diameter and depth. A macule is a flat lesion that can be seen by changes in skin color but cannot be felt. The border may be well circumscribed or may gradually blend into the surrounding skin. It may be of any size, but the term is generally used to describe lesions smaller than 1 cm. Flat lesions larger than 1 cm are termed patches. Similar to macules, papules are small (<1 cm) lesions but are palpable with the greatest mass above the surface of surrounding skin. Larger elevated skin lesions are termed plaques. Plaques may be formed by a confluence of papules or can be the primary lesion. Palpable, solitary lesions whose mass is primarily below the surface, in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, are termed either nodules (0.5-2 cm) or tumors. Tumors may be benign or malignant.

Secondary Lesions

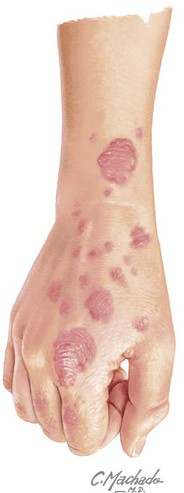

Primary lesions may undergo changes caused by evolution, irritation, infection, or application of treatments. Although it is important to recognize the secondary lesions, these changes often have less diagnostic utility than the primary lesion. Scales are layers of the stratum corneum that have desquamated but still remain attached to the skin surface. Crusts are thick accumulations of cellular debris, blood, pus, or serum. Erosions are superficial (involving only the epidermis) losses of tissue, resulting in depression of the surface. They generally heal without scar formation. In contrast, deeper tissue loss that extends into the dermis and even subcutaneous tissue is called an ulcer. Ulcers often heal with scarring. Ulceration or erosions that are linear and result from scratching are termed excoriations. Fissures form at sites of chronic inflammation. They are sharply demarcated, linear disruptions in the epidermis with extension into the dermis. Lichenification is a marked thickening of the epidermis that results in exaggeration of skin markings (Figure 122-3). Lichenification is a result of chronic irritation caused by inflammation, rubbing, or scratching.

Color of Lesions

Another important characteristic of lesions is how they compare with the patient’s normal skin color. Lesions that are darker than the surrounding skin may be hyperpigmented. Inflammation can lead to hyperpigmentation. Other examples of hyperpigmentation include nevi, transient pustular melanosis of the newborn, and café-au-lait spots (see Chapters 124 and 126). Increased dermal pigmentation often results in a bluish discoloration of lesions, such as seen in dermal melanocytosis (colloquially termed Mongolian spots). Lesions may also be hypopigmented, such as postinflammatory hypopigmentation, tinea versicolor, or ash leaf spots of tuberous sclerosis. Depigmented lesions have lost all pigment and can be differentiated from hypopigmented lesions by Wood’s lamp examination. An example of depigmented disorders is vitiligo. Whereas lesions that are pink to red may be inflammatory in origin, more intense red to purple lesions are often vascular.

Configuration of Lesions

Specific description of the shape of lesions provides further information. To label a lesion round gives little specific information, but describing it as annular (Figure 122-4) specifies a ring-shaped lesion with a raised or erythematous border and central clearing. Common examples of annular lesions include tinea infections, erythema migrans, and granuloma annulare. Discoid lesions are also round but tend to be more solid in nature. Other round lesions include nummular (Figure 122-5), targetoid (containing-concentric rings), and guttate (droplike) lesions; the latter is commonly used to describe a form of psoriasis in children that occurs after acute streptococcal infection. Umbilicated lesions have a central depression; common examples include molluscum contagiosum and varicella.

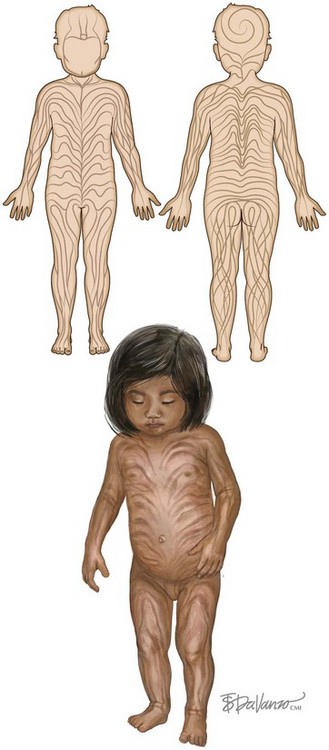

Distribution of Lesions

Many cutaneous lesions have predilections for specific areas. Although these are discussed in more detail with specific disease processes, some generalizations about lesion distribution may be helpful in initial diagnosis. Linear eruptions may follow a dermatomal pattern, thus affecting the skin supplied by a single spinal nerve. Linear lesions may also follow lines of Blaschko, lines of embryologic development of the skin (Figure 122-6). These cutaneous lesions represent a form of genetic mosaicism; examples include epidermal nevi, lichen striatus, and some congenital disorders. Lesions that arise only in sun-exposed areas may represent a disorder of photosensitization or one precipitated by sun exposure.