28 Dental Emergencies

• Adults have 32 permanent teeth. Children have 20 primary teeth.

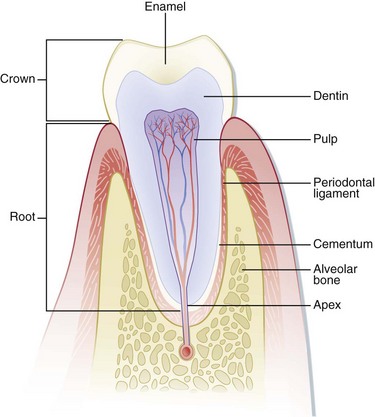

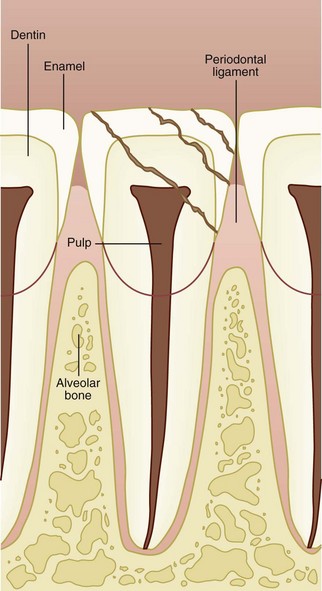

• A tooth consists of (1) the enamel, which is the outermost, hard protective layer; (2) the underlying elastic and porous dentin, which cushions the tooth during mastication and carries nutrients from the pulp to the enamel; (3) the pulp, which contains the neurovascular supply of the tooth; and (4) the cementum and the periodontal ligament, which anchor the tooth into alveolar bone.

• Use of bupivacaine in the form of a dental nerve block is an effective means of providing relief from severe odontalgia. A dental block should also be performed before manipulation of any significantly traumatized tooth.

• Radiographs are not usually necessary for most dental complaints, but they can be useful when one must search for a tooth fragment, an avulsed or intruded tooth, or a mandibular fracture.

• Any exposed dentin or pulp of an acutely fractured tooth should be covered. The covering aids in pain control and may prevent the need for a root canal.

• Subluxated or luxated teeth should be splinted if significantly loosened to prevent aspiration and maximize potential viability.

• Avulsed teeth should be placed in a storage medium immediately by emergency medical services or emergency department personnel to maximize potential viability.

Epidemiology

The incidence of dental complaints in emergency departments (EDs) appears to be rising, which may reflect the increasing use of EDs as primary care facilities.1 Injuries involving the younger population are most often secondary to falls or accidents, whereas those in older age groups are most often secondary to motor vehicle accidents, falls, or assaults.2 Traumatic dental injuries usually involve the permanent anterior dentition, but adult dentoalveolar injuries are frequently associated with fractures of the mandible and face. Patients who have fractures of both the mandibular condyle and body are more likely to have related tooth injury than are patients with either isolated body or condylar fractures.2

Structure and Function

The Stomatognathic System

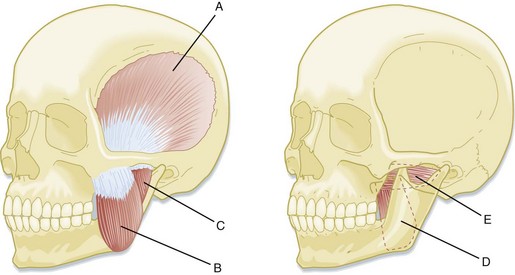

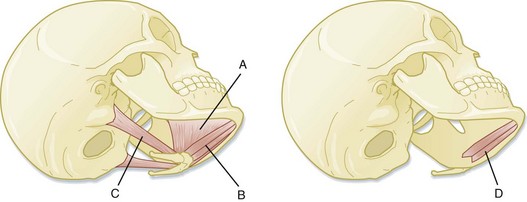

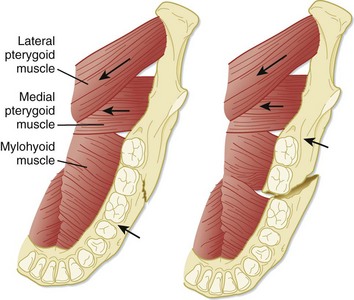

The muscles of mastication are responsible for opening and closing the mouth and are those most frequently associated with temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). The clinician should be knowledgeable about the position of the muscles to perform an examination properly and to recognize the origin of certain painful conditions. The muscles that close the mouth are those most often associated with TMDs; these muscles are the masseter, the temporalis, and the medial pterygoid (Fig. 28.1).3 Contraction of this group of muscles bilaterally serves to move the condyle superiorly and posteriorly, which causes the mouth to close. The muscles that open the mouth are the anterior digastric, posterior digastric, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and infrahyoid muscles (Fig. 28.2). The lateral pterygoid muscles are responsible for anterior translation and lateral movement of the mandible (Fig. 28.3). Unilateral contraction causes lateral movement away from the side of the muscle contraction, whereas bilateral contraction causes protrusion of the mandible.

Fig. 28.1 Muscles responsible for closing and excursive mandibular movements.

(From King R, Montgomery M, Redding S, editors. Oral-facial emergencies—diagnosis and management. Portland, OR: JBK Publishing; 1994.)

Fig. 28.2 Muscles responsible for mandibular opening.

(From King R, Montgomery M, Redding S, editors. Oral-facial emergencies—diagnosis and management. Portland, OR: JBK Publishing; 1994.)

Fig. 28.3 Axial view of the floor of the mandible.

(From Eisele D, McQuone S, editors. Emergencies of the head and neck. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000.)

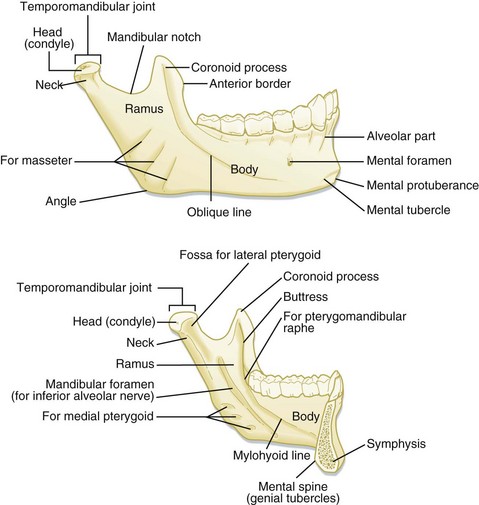

Each side of the mandible consists of the horizontal body and ascending ramus, which are connected by the angle. The bodies of the mandible are connected by the symphysis in the midline. The ascending ramus gives rise to two processes superiorly, the condylar process and the coronoid process (Fig. 28.4). The mandibular condyle, along with the mandibular fossa and the articular eminence of the temporal bone, make up the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The TMJ provides both hinge and gliding actions. Between the mandibular condyle and the articular eminence lies the meniscus, a fibrous collagen disk. A ligamentous joint capsule surrounds the TMJ and serves to limit condylar movement. TMJ pain may be caused by a number of conditions, both traumatic and nontraumatic.

Teeth

Names

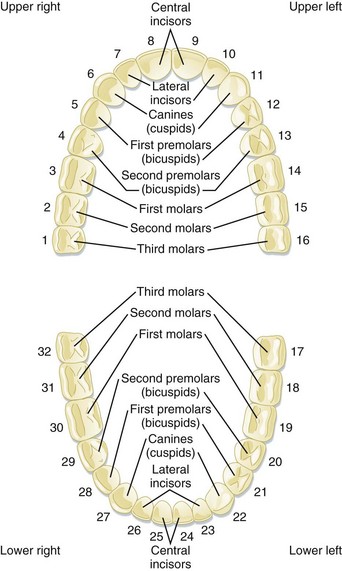

The adult dentition normally consists of 32 teeth, of which 8 are incisors, 4 are canines, 8 are premolars, and 12 are molars. From the midline to the back of the mouth on each side are a central incisor, a lateral incisor, a canine (eye tooth), two premolars, and three molars, the last of which is the troublesome wisdom tooth (Fig. 28.5).

Identification of Teeth

The primary teeth, or “baby teeth,” are also best described by determining which tooth is involved, not by its official classification. A full complement of primary teeth consists of 20 teeth: 8 incisors, 4 canines, and 8 molars. The earliest primary teeth to erupt are the central incisors, usually at 4 to 8 months. Children usually have a full complement of teeth by the time that they are 3 years old (Table 28.1).

| TOOTH DESIGNATION | NAME OF TOOTH | APPEARANCE IN THE MOUTH |

|---|---|---|

| Baby (Primary) Teeth | ||

| A | Central incisor | 4-14 mo |

| B | Lateral incisor | 8-18 mo |

| C | Canine tooth | 14-24 mo |

| D | First molar | 10-20 mo |

| E | Second molar | 20-36 mo |

| Adult (Permanent) Teeth | ||

| 1 | Central incisor | 5-9 yr |

| 2 | Lateral incisor | 6-10 yr |

| 3 | Canine tooth |  yr yr |

| 4 | First premolar (bicuspid) | 9-14 yr |

| 5 | Second premolar (bicuspid) | 10-15 yr |

| 6 | First molar (6-yr molar) | 5-9 yr |

| 7 | Second molar (12-yr molar) | 10-15 yr |

| 8 | Third molar (wisdom tooth) | 17-25 yr |

Anatomy

A tooth consists of the central pulp, the dentin, and the enamel (Fig. 28.6). The pulp contains the neurovascular supply of the tooth, which delivers nutrients to the dentin, a microporous system of microtubules. The dentin makes up the majority of the tooth and cushions it during mastication. The white, visible portion of a tooth, the enamel, is the hardest part of the body. A tooth may also be described in terms of its coronal portion (crown) or its root. The crown is covered in enamel, and the root is anchored in alveolar bone by the periodontal ligament and cementum.

The following terminology is used to describe the different anatomic surfaces of the tooth:

Facial: The part of the tooth that faces the opening of the mouth. This surface is visible when someone smiles. This is a general term applicable to all the teeth.

Labial: The facial surface of the incisors and canines.

Buccal: The facial surface of the premolars and molars.

Oral: The part of the tooth that faces the tongue or palate. This is a general term applicable to all the teeth.

Lingual: Toward the tongue; the oral surface of the mandibular teeth.

Palatal: Toward the palate; the oral surface of the maxillary teeth.

Approximal/interproximal: The contacting surfaces between two adjacent teeth.

Mesial: The interproximal surface facing anteriorly or closest to the midline.

Distal: The interproximal surface facing posteriorly or away from the midline.

Occlusal: Biting or chewing surface of the premolars and molars.

Incisal: Biting or chewing surface of the incisors and canines.

Apical: Toward the tip of the root of the tooth.

Coronal: Toward the crown or the biting surface of the tooth.

The Periodontium

The periodontium is the attachment apparatus. It consists of the gingival and periodontal subunits, which maintain the integrity of the entire dentoalveolar unit. The gingival subunit consists of gingival tissue and junctional epithelium. The periodontal subunit consists of the periodontal ligament, the alveolar bone, and the cementum of the root of the tooth (see Fig. 28.6). The gingival sulcus is the space between the attached gingiva and the tooth. The mucobuccal fold is that area of mucosa where the attached gingiva gives rise to the looser buccal mucosa. The mucobuccal fold is the area penetrated when most dental nerve blocks are performed.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

1. When did the incident occur? This is important in the evaluation of avulsed permanent teeth because the decision to reimplant a tooth is based largely on the duration of the avulsion.

2. Were any teeth found at the scene?

3. Did the patient have any symptoms suggestive of tooth aspiration, such as coughing or choking at the scene?

4. Has the patient been using alcohol or any other sedatives or recreational drugs that may have made aspiration more likely?

5. Does the patient have amnesia, which may suggest loss of consciousness?

6. Does the patient complain of pain? Do the teeth feel as though they are touching normally? Is the pain associated with occlusion? Mandibular fractures typically worsen with jaw movement, and patients complain that their bite is off. Pain from TMJ injuries is often referred to the ear. Fractured teeth frequently hurt more with the inspiration of air or contact with cold substances. Luxated or subluxated teeth hurt during mastication or chewing.

7. Did the patient take any over-the-counter analgesics or apply any substances to decrease the pain? Over-the-counter topical anesthetics can cause sterile abscesses when applied directly to the pulp.3

8. Is the tooth a permanent or a primary tooth? Avulsed primary teeth are managed differently from avulsed permanent teeth.

9. Does the patient have a history of bleeding disorders or allergies?

Additional historical information must be obtained if the complaint does not involve trauma:

1. Has the patient had any recent dental work? Dry sockets, for example, occur several days after a tooth has been extracted.

2. Does the patient have a history of poor dentition or multiple caries?

3. Is the patient having difficulty opening the mouth, which suggests a TMJ problem?

4. Has the patient had any difficulty swallowing? Has a change in voice or any shortness of breath occurred? Has any swelling developed? These symptoms suggest a possible deep space infection or hematoma.

5. Is the patient immunocompromised? Deep space infections spread rapidly to the mediastinum and cavernous sinus in an immunocompromised patient.

6. Does the patient have a coagulopathy secondary to aspirin, warfarin, or other anticoagulants or symptoms or a history suggestive of a bleeding disorder?

7. Was the time course of the problem insidious or rapid? Has the patient had symptoms of infection, such as fever, chills, or vomiting?

8. Does the patient have a history of rheumatic fever or valvular disease, such as mitral valve prolapse?4 Does the patient have artificial joints, valves, or shunts? These may predispose to endocarditis or infection of the implant or shunt if dental infection is present.

Differential Diagnosis

Nontraumatic dental emergencies usually result from poor oral hygiene, recent dental instrumentation, or infection. Uncomplicated tooth pain (odontalgia) is often pulpitis, and further diagnostic testing is not necessary in the ED. The other consideration is periodontal or pulpal infection or abscess. Nonodontogenic sources may cause referred pain to the dentition. Referred pain from the sinuses or the TMJ must also be considered, especially for pain that cannot be localized (Table 28.2). A patient who has recently undergone dental instrumentation or extraction may be seen in the ED with dry socket, hematoma, or hemorrhage.

| Odontogenic pain |

Adapted from Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JE, editors. Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

Interventions and Procedures

Physical Examination

During palpation of the anterior portion of the neck, particular attention should be paid to the area along and beneath the length of the mandibular body. The oral cavity should be examined for any bleeding, swelling, tenderness, fractures, abrasions, or lacerations, and each tooth should be percussed and accounted for. A tongue blade should be used to assess the entire mucobuccal fold region. The EP should palpate the cheek and the floor of the mouth with the thumb of a gloved hand inside the patient’s oral cavity. Each tooth should be percussed with a tongue blade for sensitivity and palpated with gloved fingers for mobility. Blood in the gingival crevice (the area where the gingiva meets the enamel) suggests a traumatized tooth or a fractured jaw (see Fig. 28.13, B). The teeth should meet symmetrically and evenly during biting, and the patient should be able to exert firm pressure on a tongue blade when biting with the molars. An inability to crack a tongue blade bilaterally when it is twisted between the molars (the tongue blade test) suggests a mandibular fracture (Fig. 28.7).

Control Of Hemorrhage

1. Apply direct pressure. Any excessive clot should be removed and the area anesthetized with local infiltration of lidocaine or bupivacaine with epinephrine. The epinephrine provides vasoconstriction, and the anesthetic enables the patient to bite harder. Anesthetic without epinephrine should generally be avoided because the amide anesthetics are vasodilators and may increase the bleeding. Next, insert dental roll gauze or a dental tampon into the space that was left by the extracted tooth. Dental roll gauze fits nicely into the extraction space and thus helps increase direct pressure. Use a folded-up 2- × 2-inch gauze pad if dental rolls are unavailable. Cover the dental roll gauze with 2- × 2-inch gauze pads and have the patient bite firmly on it for 10 to 15 minutes. It also helps to soak the dental rolls in epinephrine or phenylephrine.

2. If the bleeding persists, insert a hemostatic agent (Celox, HemCon, Surgicel, Gelfoam) into the socket. Both of the chitin-derived dressings (Celox, HemCon) have been shown to decrease bleeding better than direct pressure does, as well as to control bleeding in patients taking anticoagulants. If Gelfoam or Surgicel is used, the surrounding cusp of gingiva may require closure with a fast-absorbing suture to ensure that the dressing remains seated. Instruct the patient to bite down on gauze placed over the dressing. If HemCon or Celox is used or if not enough gingival tissue is available for closure, simply place the coagulating agent into the socket and have the patient bite down into gauze placed over the bleeding socket.

3. Topical thrombin, which can usually be obtained from the operating room, is also very effective in stopping oozing blood, but it is very expensive. Simply spraying topical thrombin onto the site and then having the patient bite into gauze generally work well.

4. Low-temperature cautery is also very effective, although it can be destructive to tissue if not used carefully. Battery-operated thermal cautery units, which are often used for nail trephination, are available in many EDs. Anesthetize the gingiva before using the cautery.

5. If the preceding measures are not effective in controlling bleeding, call a specialist. It is also reasonable to consider the use of fresh frozen plasma or platelets if a coagulopathy is determined to be present.

Management of Pain

The use of bupivacaine in dental block anesthesia affords the patient the luxury of 8 to 12 hours of relative comfort until follow-up with a dentist is possible. Likewise, the use of narcotics is minimized because the patient’s pain has been relieved. Topical anesthesia in the form of 20% benzocaine or 5% lidocaine is also a valuable aid because both agents decrease the pain of intraoral injection. It behooves the EP to be able to use them properly.5

Diagnostic Testing

A panoramic facial radiograph (Panorex) and a Towne view are probably the most useful and cost-effective radiographs for evaluating mandibular trauma in the ED.6 A panoramic radiograph of the mandible shows the mandible in its entirety and demonstrates fractures in all regions, including the symphysis.6 Occasionally, however, such a radiograph can miss overriding anterior fractures; if these fractures are probably present, computed tomography (CT) is indicated. The Towne view allows better visualization of the condyles than a panoramic radiograph does. A coronal CT scan is more definitive and is often used for preoperative evaluation, but it is seldom necessary for the diagnosis of isolated mandibular trauma. CT should be performed if multiple facial fractures are suspected or if the initial radiographic findings for the mandible are equivocal and clinical suspicion is high.6,7 If the patient is immobilized, mandibular films or CT scanning may be obtained. Mandibular films may miss the symphysis, and if the clinician is concerned about a symphyseal fracture, either occlusal films or a CT scan should be obtained.

Dental abscesses or infections are best treated by antibiotics, incision and drainage, or both. Although panoramic radiographic views can visualize sizable periapical abscesses, their routine use in the ED is not warranted because their results would not change the treatment and disposition of the patient.3 Bite-wing radiographs, obtained in the dentist office, are the standard for diagnosing small periapical abscesses and caries. Deep space infections of the head and neck are often difficult to localize by physical examination, and CT scanning has become the modality of choice to delineate collections of abscess or cellulitis of the face and neck.8

Treatment and Disposition

Trauma

Fractured Teeth

1. Identify all fracture fragments and mobile teeth, and note whether a mandibular fracture is open or closed. Radiographs should be taken if fragments have intruded into the mucosa or alveolar bone. Perform chest radiography if there is any concern about aspiration of a tooth or tooth fragment.

2. The dentition is much more easily manipulated if the patient is not in significant discomfort. Tooth infiltration and dental block anesthesia should be part of the EP’s armamentarium. Narcotic and nonnarcotic alternatives, though helpful after treatment is completed, do not usually offer the patient enough comfort to allow the performance of most dental manipulations.

ED management of fractured teeth depends on the extent of fracture with regard to the pulp, the extent of development of the apex of the tooth, and the age of the patient.9 Many classification systems are used for describing injured dentition, such as the Ellis system; however, most dentists and maxillofacial surgeons do not use this nomenclature. The most easily understood method of classification is based on a description of the injury.10

Crown Fractures

Uncomplicated crown fractures through the enamel only are not usually sensitive to forced air, temperature, or percussion and generally pose no real threat to the dental pulp. ED treatment is not necessary but may consist of smoothing the sharp edges with an emery board if they are significantly bothersome to the patient. The patient should be reassured that the dentist can restore the tooth with bonding composites and resins. Follow-up is important because pulp necrosis and color change can occur, though rarely (0% to 3% of cases) (Figs. 28.8 and 28.9).11

Uncomplicated fractures that extend through the enamel and dentin are at higher risk for pulp necrosis and need more aggressive treatment (Fig. 28.10; also see Fig. 28.8). The risk for pulp necrosis in these patients is 1% to 7% but increases as time until treatment extends beyond 24 hours.12 Affected patients usually have sensitivity to forced air, percussion, and extremes of temperature. Physical findings are notable for the yellowish tint of the dentin in contrast to the white hue of the enamel. Fractures that are close to the pulp reveal a slight pink coloration. Dentin is porous, which allows oral flora to pass into the pulp chamber and thereby possibly facilitates inflammation and infection. This process occurs predominantly after 24 hours but may do so earlier if the fracture is closer to the pulp. Patients younger than 12 years have a higher pulp-to-dentin ratio than adults do and are therefore at higher risk for pulp contamination. Dentin fracture in a younger patient should be treated more aggressively, and the patient should be seen by a dentist within 24 hours.12

The two primary reasons to treat dental fractures in the ED are (1) to cover the exposed dentin and prevent inflammation and infection and (2) to provide relief of pain. If a tooth is properly covered in the ED, a dentist can later rebuild it with modern composites. A tooth nerve block should be performed before covering the tooth. Dressings that may be considered for covering tooth fractures include calcium hydroxide paste, zinc oxide paste, zinc oxide eugenol, glass ionomer composites, and cyanoacrylates.13–15 Some emergency medicine texts support the use of glass ionomer cements in the ED; however, this issue is controversial in the dental community. The ease of use, affordability, and inherent properties of calcium hydroxide paste make it an attractive option in the ED. It is watertight, dries on contact with saliva, is durable, and is pH compatible (Fig. 28.11). Composites that are applied with a bonding light are beyond the scope of most emergency medicine practice. Bone wax is sometimes used but is not recommended because it is slightly porous and cannot be used as a base in rebuilding the tooth. Skin adhesives have been used in fracture repair, but they last only a short time inside the mouth and cannot be used as a base in tooth restorations. Their use will probably become more commonplace if their durability improves and clinical studies corroborate their usefulness.

Complicated fractures of the crown involving the pulp are true dental emergencies (Fig. 28.12; see Fig. 28.8). They lead to pulp necrosis at least 10% to 30% of the time, even with rapid, appropriate dental treatment.11 Such fractures are distinguished by the pink-red tinge of the pulp. They are usually severely painful, but lack of sensitivity occasionally occurs secondary to disruption of the neurovascular supply of the tooth. Immediate management involves referral to a dentist, endodontist, or oral surgeon. These fractures generally require pulpectomy (complete pulp removal) or, in the case of primary teeth, pulpotomy (partial pulp removal) as definitive treatment.12,16,17 The longer the pulp is exposed, the greater the chance for abscess development or pulp necrosis. If a dentist cannot see the patient immediately, the EP should relieve the pain with a supraperiosteal injection and cover the pulp with one of the dressings described previously. If bleeding is brisk, it can usually be controlled by having the patient bite onto a gauze pad soaked with epinephrine or phenylephrine. Alternatively, injecting a small amount of lidocaine with epinephrine into the pulp will stop the bleeding and poses no threat to the tooth because the pulp needs to be removed regardless.

If the exposure was prolonged, many authorities and dentists would advocate antibiotic prophylaxis with penicillin or clindamycin, although the effectiveness of this approach has never been proved.18 With regard to antibiotic prophylaxis for dental fractures, it is important to remember the following assumptions: it is uncertain when many patients will be able to secure follow-up, and delayed fracture care and poor gingival health raise the risk for pulp necrosis and, potentially, the development of an abscess. Therefore, although it has not been proved that antibiotics are useful in patients with dentin or pulp fractures, such treatment should be considered if the patient has the previously mentioned risk factors or if the consulting dental professional has requested them.

Luxation and Subluxation

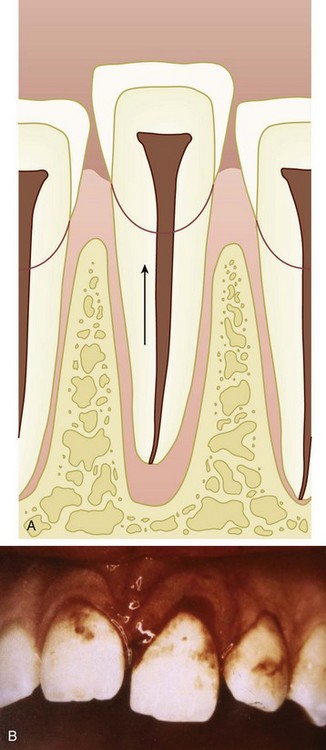

Extrusive luxation: The tooth is displaced in a direction toward the crown (Fig. 28.13).

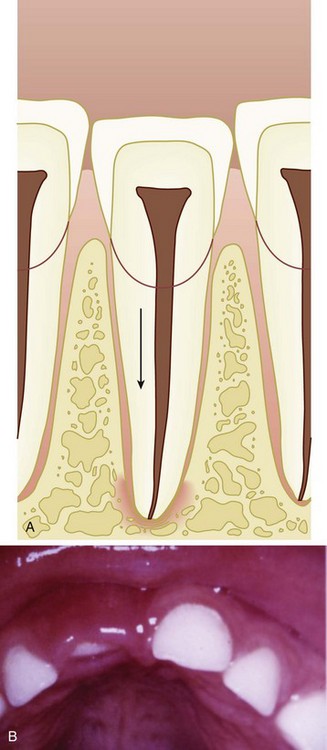

Intrusive luxation: The tooth is forced apically toward the root of the tooth; it may be associated with crushing or fracture of the apex of the tooth (Fig. 28.14).

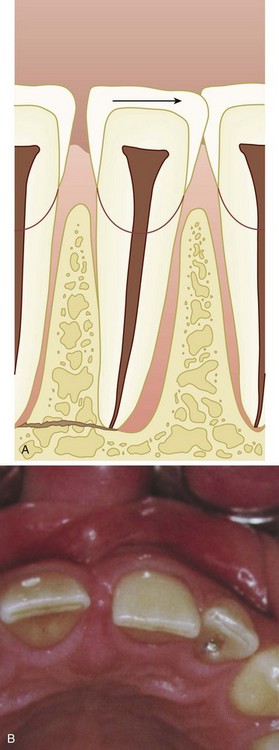

Lateral luxation: The tooth is displaced facially, mesially, lingually, or distally (Fig. 28.15).

Complete luxation: The tooth is completely avulsed out of its socket (Fig. 28.16).

Coe-Pak, a commercially available form of periodontal paste, is a very sticky dressing that becomes firm after application (Fig. 28.17). Periodontal paste is also very useful as a primary treatment of gingival and palatal lacerations, with the caveat that the paste must be removed by a dental professional. Self-cure composite is another reasonable splinting option in the ED. Self-cure composite does not require etching acids or bonding lights and is easy to use (Fig. 28.18). The disadvantage of self-cure composite is that it is rigid and inflexible and tends to pop off with slight movement of the teeth before the patient sees a dentist. Both splinting techniques are easily removed by a dentist or oral surgeon during formal restoration.

Intrusion and Avulsion

Time since avulsion is the most important determinant in the decision whether to reimplant an avulsed tooth. Generally, the longer the tooth is out of its socket, the higher the incidence of periodontal ligament necrosis and subsequent reimplantation failure.18 Periodontal ligament cells usually die within 1 to 2 hours if not placed in an appropriate transport medium.19,20 Many studies have been conducted on the various storage media used to keep the cells of the periodontal ligament viable. Milk, Hank’s balanced salt solution, EMT Toothsaver, Save a Tooth (commercial formulations of Hank’s solution), saliva, water, and Gatorade have all been studied. Cell culture formulations have been developed that cause periodontal ligament cells to not only remain viable but also proliferate; however, they are not practical for ED use. To date, warmed milk and warmed Hank’s solution (generic or commercial formulation) are best for prehospital and ED use.20 They each preserve the periodontal ligament for at least 4 to 8 hours, although reimplantation should take place as rapidly as reasonably possible.

The tooth should be placed in some sort of storage medium immediately after avulsion if possible because even 5 to 10 minutes of exposure to air will begin to cause desiccation and death of periodontal ligament cells. Saline is less optimal than the media mentioned earlier but should be used before water or saliva if it is the only option.21 The tooth should be reimplanted into the socket at the scene by paramedics, but if they are unable to do so, the tooth should be reimplanted as soon as possible in the ED. Preparation of the socket, including suctioning and irrigation, can take place while the tooth is soaking in the storage medium. The patient’s tetanus status should be updated as necessary and the patient discharged home on a soft diet. Many dental professionals recommend antibiotics effective against mouth flora (penicillin or clindamycin) to decrease inflammatory resorption of the root after fractures or avulsions.12,14,17 This, however, has never been proved to be necessary or beneficial. Treatment with antibiotics should be tailored to the individual patient after discussion with the consultant who will see the patient later.

Alveolar Bone Fractures

Treatment consists of rigid splinting of the affected segment, which should be performed urgently by an oral surgeon or dentist. It should ideally be done within 24 hours, but the urgency depends on the extent, mobility, and displacement of the affected segment. The role of the EP is to diagnose the injury, identify any avulsed or fractured teeth, and preserve as much of the alveolar bone and surrounding mucosa as possible. Alveolar bone that is lost, débrided, or missing is difficult for the specialist to repair properly.14 Patients with alveolar ridge fractures, if nonmobile with good hemostasis, may be discharged with next-day follow-up, but most will require admission or transfer for repair.

Alveolar Osteitis (Dry Socket)

Dry socket pain is severe and frequently requires intervention other than oral pain medication. Alveolar osteitis is associated with severe postextraction pain that occurs when alveolar bone becomes exposed and inflamed. It typically occurs when a clot that is present after a tooth extraction becomes dislodged or prematurely dissolves, most commonly 2 to 4 days after a tooth extraction. The cause of disruption of the clot is not completely agreed on but is thought to be secondary to locally increased fibrinolytic activity.22 The examination is unremarkable with the exception of the missing clot, which is not always obvious to the untrained eye. Smoking, drinking from a straw, periodontal disease, hormone replacement therapy, and being a female are all risk factors predisposing a patient to dry socket.22 This complication occurs after 2% to 5% of all extractions, although the rate increases if the extraction was especially traumatic or involves an impacted mandibular third molar.3,11,22

Antibiotics can be given to patients with alveolar osteitis, but this is not a common practice, and dry socket heals completely once the socket has been covered. Antibiotics should be prescribed only after consultation with the patient’s dentist or oral surgeon.11

Dental Infections

In the ED differentiation between periapical abscesses and pulpitis is very difficult, and dental bite-wing radiographs are seldom available. Therefore, some physicians begin antibiotic therapy in patients who have not undergone recent dental instrumentation but complain of tooth pain and exhibit tenderness with percussion. Routine administration of antibiotics for tooth pain that is caused by pulpitis, instrumentation, or a localized abscess is not recommended by the dental societies, and a study in the emergency medicine literature suggests that the use of antibiotics for undifferentiated dental pain is not necessary.23,24 Antibiotics have been recommended for odontogenic infections that have spread outside the immediate periapical area or have associated systemic signs, such as fever, swelling, and trismus. Supraperiosteal infiltration (tooth nerve block) should be performed in most cases, not only to provide immediate and long-acting relief but also because it reduces the need for narcotic analgesics even after the anesthetic has worn off.

Deep Space Infections of the Head and Neck

Deep space infections can rapidly become severe and life-threatening. The submandibular space connects to the sublingual space, and bilateral involvement of the sublingual spaces can result in a condition known as Ludwig angina, an airway-compromising deep space infection that may require airway intervention (Fig. 28.19).

Management of complicated odontogenic head and neck infections focuses primarily on airway management, surgical drainage, and antibiotics. CT has become the imaging modality of choice for deep space infections of the head and neck and should be used to localize and delineate collections of abscess or cellulitis that cannot be precisely determined by physical examination.8 Airway intervention should be performed early if there is any question of compromise. The EP should administer antibiotics intravenously and obtain surgical consultation early in evaluation and treatment of the patient.

The bacteria usually isolated from deep space infections of the head and neck typically consist of mixed Staphylococcus and Streptococcus or mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora. Almost half the isolates from odontogenic infections are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics.25 Drugs of choice include penicillin G plus metronidazole or extended-spectrum penicillins such as ampicillin-sulbactam, ticarcillin-clavulanate, and piperacillin-tazobactam. These combination antibiotics are effective against β-lactamase–producing bacteria, as well as common oral anaerobes such as Bacteroides fragilis. Clindamycin is an effective choice for penicillin-allergic patients, but it should be combined with a cephalosporin such as cefotetan or cefoxitin for resistant organisms. It is prudent to remember that antibiotics are adjunctive therapy only and not a substitute for surgical therapy.

1 Waldrop R, Ho B, Reed S. Increasing frequency of dental patients in the urban ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:687–689.

2 Bringhurst C, Herr RD, Aldous JA. Oral trauma in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:486–490.

3 King R, Montgomery M, Redding S. Oral-facial emergencies—diagnosis and management. Portland, OR: JBK Publishing; 1994.

4 Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA. 1997;277:1794–1801.

5 Jastak T, Yagiela J, Donaldson D. Local anesthesia of the oral cavity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995.

6 Druelinger L, Guenther M, Marchand EG. Radiographic evaluation of the facial complex. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:393–410.

7 Markowitz BL, Sinow JD, Kawamoto Jr, HK., et al. Prospective comparison of axial computed tomography and standard and panoramic radiographs in the diagnosis of mandibular fractures. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:163–169.

8 Lazor JB, Cunningham MJ, Eavey RD, et al. Comparison of computed tomography and surgical findings in deep neck infections. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:746–750.

9 Rauschenberger CR, Hovland EJ. Clinical management of crown fractures. Dent Clin North Am. 1995;39:25–51.

10 Ellis SG. Incomplete tooth fracture: proposal for a new definition. Br Dent J. 2001;190:424–428.

11 Dale RA. Dentoalveolar trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:521–538.

12 McTigue D. Diagnosis and management of dental injuries in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2000;47:1067–1084.

13 Rauschenberger CR, Hovland EJ. Clinical management of crown fractures. Dent Clin North Am. 1995;39:25–51.

14 Blatz M. Comprehensive treatment of traumatic fracture and luxation injuries in anterior permanent dentition. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13:273–279.

15 Bakland LK, Milledge T, Nation W. Treatment of crown fractures. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1996;24:45–50.

16 Turkistani J, Hanno A. Recent trends in the management of dentoalveolar traumatic injuries to primary and young permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2011;27:46–51.

17 Andreasen JO, Lauridsen D, Andreasen FM. Contradictions in the treatment of traumatic dental injuries and ways to proceed in dental trauma research. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:16–22.

18 Barrett EJ, Kenny DJ. Avulsed permanent teeth: a review of the literature and treatment guidelines. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13:6153–6318.

19 Marino TG, West LA, Liewehr F, et al. Determination of periodontal ligament cell viability in long shelf-life milk. J Endod. 2000;26:699–702.

20 Souza DDL, Lückmeyer DD, Felippe WT, et al. Effect of temperature and storage media on human periodontal ligament fibroblast viability. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:271–275.

21 Olson BD, Mailhot JM, Anderson RW, et al. Comparison of various transport media on human periodontal ligament cell viability. J Endod. 1997;23:676–679.

22 Noroozi AR, Philbert R. Modern concepts in understanding and management of the “dry socket” syndrome: comprehensive review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:30–35.

23 Ashman S. Oral cavity and dental emergencies. In: Eisele D, McQuone D. Emergencies of the head and neck. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000.

24 Runyon MS, Brennan MT, Batts JJ, et al. Efficacy of penicillin for dental pain without overt infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1268–1271.

25 Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Elipoulos GM, et al. Sanford guide to antimicrobial therapy. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy; 2005.