Chapter 304 Dental Caries

Etiology

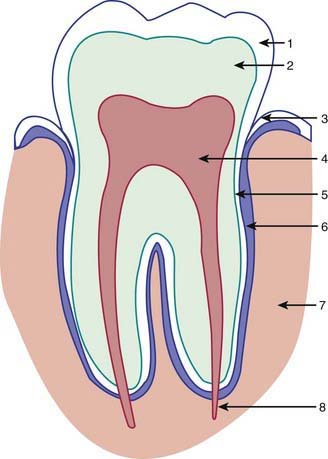

The development of dental caries depends on interrelationships among the tooth surface, dietary carbohydrates, and specific oral bacteria. Organic acids produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary carbohydrates reduce the pH of dental plaque adjacent to the tooth to a point where demineralization occurs. The initial demineralization appears as an opaque white spot lesion on the enamel, and with progressive loss of tooth mineral, cavitation of the tooth occurs (Fig. 304-1).

Clinical Manifestations

Dental caries of the primary dentition usually begins in the pits and fissures. Small lesions may be difficult to diagnose by visual inspection, but larger lesions are evident as darkened or cavitated lesions on the tooth surfaces (Fig. 304-2). Rampant dental caries in infants and toddlers, referred to as early childhood caries (ECC), is the result of a child colonized early with cariogenic bacteria and the frequent ingestion of sugar, either in the bottle or in solid foods. The carious process in this situation is initiated earlier and consequently can affect the maxillary incisors first and then progress to the molars as they erupt.

Complications

Left untreated, dental caries usually destroy most of the tooth and invade the dental pulp (Fig. 304-3), leading to an inflammation of the pulp (pulpitis) and significant pain. Pulpitis can progress to pulp necrosis, with bacterial invasion of the alveolar bone causing a dental abscess (Fig. 304-4). Infection of a primary tooth can disrupt normal development of the successor permanent tooth. In some cases this process leads to sepsis and infection of the facial space.

Prevention

Fluoride

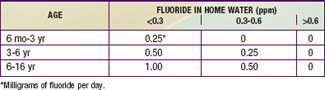

The most effective preventive measure against dental caries is communal water supplies optimized to 1 ppm fluoride. Children who reside in areas with fluoride-deficient water supplies and are at risk for caries benefit from dietary fluoride supplements (Table 304-1). If the patient uses a private water supply, it is necessary to get the water tested for fluoride levels before prescribing fluoride supplements. To avoid potential overdoses, no fluoride prescription should be written for more than a total of 120 mg of fluoride. However, because of confusion regarding fluoride supplements among practitioners and parents, association of supplements with fluorosis, and lack of parent compliance with the daily administration, supplements may no longer be the first-line approach for preventing caries in preschool children.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Pediatric Dentistry and Oral Health. Preventive oral health intervention for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1387-1394.

Ammari JB, Baqain ZH, Ashley PF. Effects of programs for prevention of early childhood caries. A systematic review. Med Princ Pract. 2007;16:437-442.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Populations receiving optimally fluoridated public drinking water—United States, 1992–2006. MMWR. 2008;57:737-740.

Cheng KK, Chalmers I, Sheldon TA. Adding fluoride to water supplies. BMJ. 2007;335:699-702.

Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2007;11:248.

The Lancet. Oral health: prevention is key. Lancet. 2009;373:1.

Milgrom P, Ly KA, Tut OK, et al. Xylitol pediatric topical oral syrup to prevent dental caries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:601-606.

Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369:51-58.

Twetman S. Prevention of early childhood caries (ECC)—review of literature published 1998–2007. Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:12-18.

Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, June B. Fluoride varnish efficacy in preventing early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2006;85:172-176.