CHAPTER 152 Demyelinating Disease

There is thus no better example of the need for caution in the preoperative diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) lesions than with demyelinating disease.1 The diagnosis of grade II infiltrating glioma (astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, or mixed glioma) in a patient with an enhancing lesion is almost by definition contradictory because these low-grade tumors are nonenhancing. In the event of such discordance, the pathologist can re-review the slides, and the neuroradiologist might revisit the images. “Could this be demyelinating disease?” Ideally, any clinical suspicions about demyelinating disease are relayed to the pathologist at the time that the specimens are delivered, but the pathologist needs to consider demyelinating disease without prompting because there are often few, if any such clinical suspicions in biopsied lesions, particularly when solitary.

The chance that such lesions will be subjected to biopsy can be minimized by an interdisciplinary approach that mandates full consideration of non-neoplastic diseases before the diagnosis of a tumor is accepted.2 This should be done even in the face of an ominous contrast-enhancing mass, for which tumor is the neurosurgeon’s visceral impression.

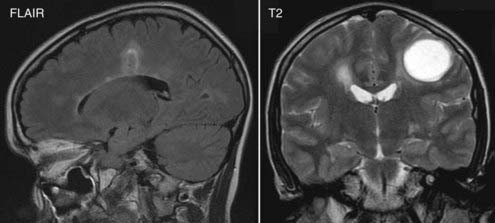

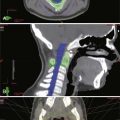

Neuroradiologically, demyelinating disease has both quantitative and qualitative features that aid in identification. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has revolutionized the diagnosis; several MRI features are believed to be suggestive. Classic demyelinating plaques are typically T2 hyperintense and located within the periventricular white matter of the corona radiata and centrum semiovale (Fig. 152-1). In addition, the lesions are usually ovoid with their main axis perpendicular to the corpus callosum and parallel to the course of the intramedullary cerebral veins. These so-called Dawson’s fingers result from the fact that such plaques are predominantly perivenular (see Fig. 152-1). Coronal MRI is especially helpful in identification. In addition, extension of the lesion into the corpus callosum is also best seen on coronal imaging. Demyelinating plaques are generally small but may be confluent. Large solitary lesions may be confused with malignant tumors. Multiple examples raise the possibility of metastases, multicentric glioma, and primary CNS lymphoma, although metastases affect gray matter, and the age and clinical state make primary CNS lymphoma most unlikely except for patients with immunosuppression. Lesions involving the optic radiation or optic nerves are also highly suspect.

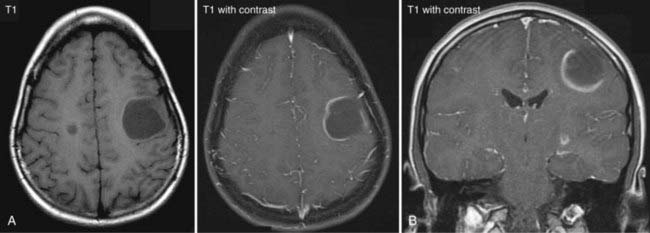

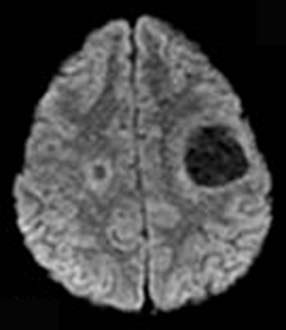

More than the site of the lesion or lesions, valuable as they are, it is the pattern of contrast enhancement that is the key index feature that helps differentiate tumefactive demyelination from malignant gliomas or abscesses. Acute areas of demyelination may reveal strong peripheral enhancement after the intravenous injection of contrast medium (Fig. 152-2A and B) that may be mistaken for that of a malignant glioma or intracerebral infection. Unlike malignant gliomas, however, the peripheral enhancing rim is often incomplete or “open” (open ring) (see Fig. 152-2A and B).3–5 The gap faces toward the brain surface with subcortical plaques and toward the ventricle with subependymal lesions. The area of enhancement may also resemble a crescent and involve only white matter. Coronal images are especially useful in detecting the opening for lesions in the latter site. Gliomas and abscesses typically show a closed ring of enhancement. Abscesses frequently have a closed, thin, and smooth ring of enhancement, whereas a thick, irregular closed ring is seen with necrotic malignant neoplasms. Another helpful feature is the degree of perilesional edema. Areas of demyelination generally have little or no perilesional vasogenic edema, whereas abscesses and high-grade gliomas typically have extensive vasogenic edema. There are occasional edema-generating demyelinating lesions, however. With the ongoing development of more functional MRI techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging, perfusion-weighted imaging, MR spectroscopy, and the latest developments in MRI such as pH-weighted MRI, more reliable differentiation may be possible (Fig. 152-3).

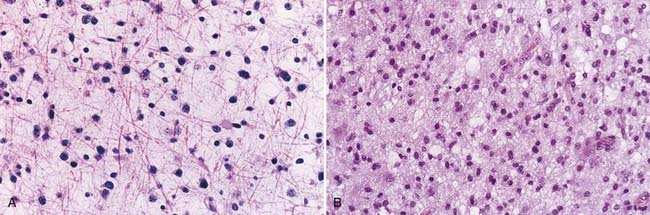

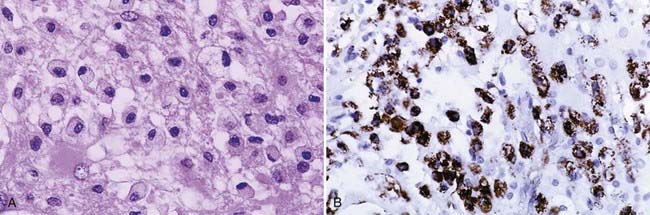

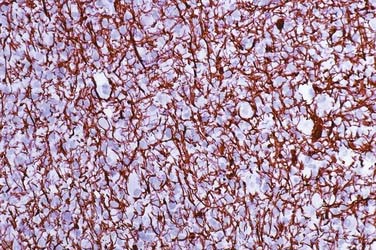

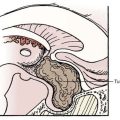

Histologically, demyelinating plaques are notoriously similar to infiltrating astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (Fig. 152-4A and B), and the diagnosis is often by no means trivial or intuitive even if the possibility is entertained and frequently almost impossible if it is not.6 A diagnosis of glioma, usually a clinical diagnosis in biopsied cases, is almost inevitable in the latter scenario. Nevertheless, there are distinctive features, of course not all present in a given patient, that are recognized with greater or lesser ease depending on the size, condition, and representativeness of the specimen. Such features include (1) a sharp border; (2) perivascular lymphocytes; (3) macrophage infiltrate (Fig. 152-5A and B), which is especially well seen in intraoperative smear preparations; (4) preserved axons, which may be seen in smears and frozen section but are usually visualized with the aid of special stains of permanent sections (Fig. 152-6); and (5) multinucleated reactive astrocytes (“Creutzfeldt cells”), which although nonspecific, are helpful in at least raising the possibility of the disease. As with neuroimaging, awareness of the possibility is the key.

Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Tumors of the central nervous system. In: AFIP Tumor Atlas. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2007.

Burger PC, Scheithauer BW, Lee RR, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to avoid the overtreatment of patients with central nervous systems lesions. Cancer. 1997;80:2040-2046.

Maarouf M, Kuchta J, Miletic H, et al. Acute demyelination: diagnostic difficulties and the need for brain biopsy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:961-969. discussion 969

Masdeu JC, Moreira J, Trasi S, et al. The open ring. A new imaging sign in demyelinating disease. J Neuroimaging. 1996;6:104-107.

Masdeu JC, Quinto C, Olivera C, et al. Open-ring imaging sign: highly specific for atypical brain demyelination. Neurology. 2000;54:1427-1433.

Smirniotopoulos JG, Murphy FM, Rushing EJ, et al. Patterns of contrast enhancement in the brain and meninges. Radiographics. 2007;27:525-551.

1 Maarouf M, Kuchta J, Miletic H, et al. Acute demyelination: diagnostic difficulties and the need for brain biopsy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:961-969. discussion 969

2 Burger PC, Scheithauer BW, Lee RR, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to avoid the overtreatment of patients with central nervous systems lesions. Cancer. 1997;80:2040-2046.

3 Masdeu JC, Moreira J, Trasi S, et al. The open ring. A new imaging sign in demyelinating disease. J Neuroimaging. 1996;6:104-107.

4 Masdeu JC, Quinto C, Olivera C, et al. Open-ring imaging sign: highly specific for atypical brain demyelination. Neurology. 2000;54:1427-1433.

5 Smirniotopoulos JG, Murphy FM, Rushing EJ, et al. Patterns of contrast enhancement in the brain and meninges. Radiographics. 2007;27:525-551.

6 Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Tumors of the central nervous system. In: AFIP Tumor Atlas. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2007.