Chapter 106 Delivery of Health Care to Adolescents

The Society for Adolescent Medicine identified 10 program and policy characteristics to ensure comprehensive and high-quality care to adolescents. Health insurance coverage that is affordable, continuous, and not subject to exclusion for preexisting conditions should be available for all adolescents and young adults who have no access to private insurance. Comprehensive, coordinated benefits should meet the developmental needs of adolescents, particularly for reproductive, mental health, dental, and substance abuse services. Safety net providers and programs, such as school-based health centers, community health centers, family planning services, and clinics that treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in adolescents and young adults, need to have assured funding for viability and sustainability. Quality of care data should be collected and analyzed by age so that the performance measures for age-appropriate health care needs of adolescents are monitored. Affordability is important for access to preventive services. Family involvement should be encouraged, but confidentiality and adolescent consent are critically important. Health plans and providers should be adequately compensated to support the range and intensity of services required to address the developmental and health service needs of adolescents. Health care providers, trained and experienced, to care for adolescents should be available in all communities. The creation and dissemination of provider education about adolescent preventive health guidelines have been demonstrated to improve the content of recommended care (Table 106-1). The ease of recognition or expectation that an adolescent’s needs can be addressed in a setting relates to the visibility and flexibility of sites and services. Staff at sites should be approachable, linguistically capable, and culturally competent. Health services should be coordinated to respond to goals for adolescent health at the local, state, and national levels. The coordination should address service financing and delivery in a manner that reduces disparities in care.

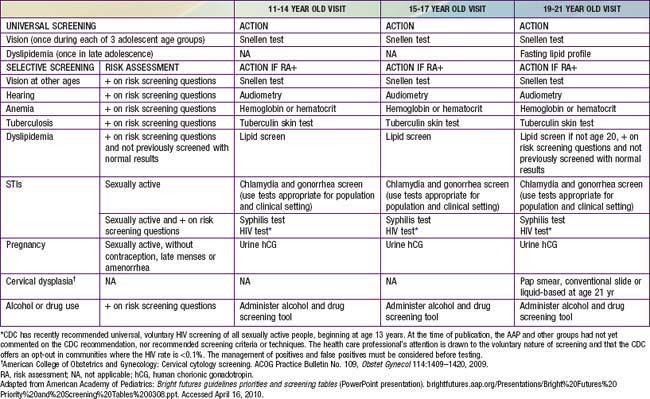

Table 106-1 BRIGHT FUTURES/AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PREVENTIVE HEALTH CARE FOR 11-21 YEAR OLDS

| PERIODICITY AND INDICATIONS | |

|---|---|

| HISTORY | Annual |

| MEASUREMENTS | |

| Body mass index | Annual |

| Blood pressure | Annual |

| SENSORY SCREENING | |

| Vision | At 11, 15, and 18 year visits or if risk assessment positive |

| Hearing | If risk assessment positive |

| DEVELOPMENTAL/BEHAVIORAL ASSESSMENT | |

| Developmental surveillance | Annual |

| Psychosocial/behavioral assessment | Annual |

| Alcohol and drug use assessment | If risk assessment positive |

| PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | Annual |

| PROCEDURES | |

| Immunization* | Annual |

| Hematocrit or hemoglobin | If risk assessment positive |

| Tuberculin test | If risk assessment positive |

| Dyslipidemia screening | If risk assessment positive |

| STI screening | If sexually active |

| Cervical dysplasia screening† | Annual beginning at age 21 yr |

| ORAL HEALTH | Annual refer to dental home or administer oral health risk assessment |

| ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE | Annual‡ |

* Schedules as per the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, published annually in the January issue of Pediatrics.

† American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Cervical cytology screening. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 109, Obstet Gynecol 114:1409–1420, 2009.

‡ Refer to specific guidance by age as listed in Bright Futures Guidelines.

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics and Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule. In Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors: Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2008, American Academy of Pediatrics. brightfutures.aap.org/pdfs/Guidelines_PDF/20-Appendices_PeriodicitySchedule.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2010.

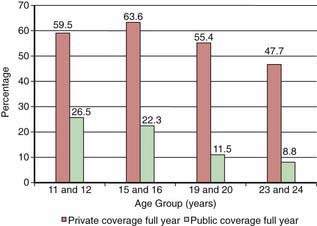

Adolescents have the lowest annual rate of visits to office-based physicians compared with all other age groups. Adolescents 10-19 yr of age are less likely to have had a recent health care visit than children <10 yr of age. In 2005, 83% of adolescents had one or more contacts with a health care professional compared with 91% of children <10 yr of age. Uninsured adolescents are the least likely to receive care. In 2005, the proportion of adolescents without health insurance who had not visited a health care provider in the past year was more than 3 times as high as insured adolescents. Older teens and young adults are more likely to be uninsured (Fig. 106-1). In 2006, while 86% of 11-12 yr olds were covered by either public or private health insurance, only 67% of 19-20 yr olds and 56.5% of 23-24 yrs olds had were covered by health care insurance. Even for insured adolescents and young adults, health care expenses present a barrier to care. In 2004, 80% of adolescents 10-21 yr of age incurred out-of-pocket expenses for health care; on average, this was $1,514 annually. Adolescents with health insurance were considerably more likely to have incurred out-of-pocket expenses and the average annual out-of-pocket amount spent was higher for insured compared to uninsured adolescents.

Figure 106-1 Full-year private and public health insurance coverage by age, 2006.

(Data from Public Policy Analysis and Education Center for Middle Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adults Health. National Health Interview Survey, 2006. Adapted from Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, et al: Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States, J Adolesc Health 45:8-24, 2009.)

The complexity and interaction of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial developmental processes during adolescence require sensitivity and skill on the part of the health professional (Chapter 104). Health education and promotion as well as disease prevention should be the focus of every visit. In 2008, the American Academy of Pediatrics in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, published the 3rd edition of Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, that offers providers a strategy for delivery of adolescent preventive health services with screening and counseling recommendations for early, middle, and late adolescence (Table 106-2). Bright Futures is rooted in the philosophy of preventive care and reflects the concept of caring for children in a “medical home.” These guidelines emphasize effective partnerships with parents and the community to support the adolescent’s health and development.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) currently recommends 3 routine adolescent vaccines, tetanus–diphtheria–acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap), the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4) and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, for universal administration beginning at the 11-12 yr old visit or as soon as possible (Chapter 165). ACIP recommends a second varicella vaccine, annual influenza vaccination, and hepatitis A vaccination in states or communities where routine hepatitis A vaccination has been implemented and for travelers, men who have sex with men, injection drug users, and those with chronic liver disease or clotting factor disorders.

The time spent on various elements of the screening will vary with the issues that surface during the assessment. For gay and lesbian youth (Chapter 104.3), emotional and psychologic issues related to their experiences, from fear of disclosure to the trauma of homophobia, may direct the clinician to spend more time assessing emotional and psychologic supports in the young person’s environment. For youths with chronic illnesses or special needs, the assessment of at-risk behaviors should not be omitted or de-emphasized by assuming they do not experience the “normal” adolescent vulnerabilities.

106.1 Legal Issues

Some minor consent laws are based on services a minor is seeking, such as emergency care, sexual health care, substance abuse, or mental health care (Table 106-3). All 50 states and the District of Columbia explicitly allow minors to consent for their own health services for STIs. About 25% of states require that minors be a certain age (generally 12-14 yr) before they are allowed to consent for their own care for STIs. No state requires parental consent for STI care or requires that providers notify parents that an adolescent minor child has received STI services, except in limited or unusual circumstances.

Table 106-3 TYPES OF MINOR CONSENT STATUTES OR RULES OF COMMON LAW THAT ALLOW FOR THE MEDICAL TREATMENT OF A MINOR PATIENT WITHOUT PARENTAL CONSENT

| LEGAL EXCEPTIONS TO INFORMED CONSENT REQUIREMENT | MEDICAL CARE SETTING |

|---|---|

| The “emergency” exception | Minor seeks emergency medical care. |

| The “emancipated minor” exception |

From Table 1 in Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Consent for emergency medical services for children and adolescents, Pediatrics 111:703–706, 2003.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Policy Statement. Consent for emergency medical services for children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;111:703-706.

Ford C, English A, Sigmond G. Confidential healthcare for adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:1-8.

Fox HB, Limb SJ. State policies affecting the assurance of confidential care for adolescents. Washington, DC: Incenter Strategies, April 2008, www.incenterstrategies.org/jan07/factsheet5.pdf.

The Alan Guttmacher Institute. Minors’ access to STI services. State policies in brief. Guttmacher Institute. June 1, 2010. www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_MASS.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2010

Weiss C. Protecting minors’ health information under the federal medical privacy regulations. American Civil Liberties Union; 2003.

106.2 Screening Procedures

Interviewing the Adolescent

Barriers to an effective interview occur when the interviewer is distracted by other events or individuals in the office, when there are extreme time limitations obvious to either party, or when there is expressible discomfort with either the patient or the interviewer. The need for an interpreter when a patient is hearing impaired or if the patient and interviewer are not language compatible provides a challenge but not necessarily a barrier under most circumstances (Chapter 4). Observations during the interview can be useful to the overall assessment of the patient’s maturity, presence or absence of depression, and the parent-adolescent relationship. Given the key role of a successful interview in the screening process, adequate training and experience should be sought by clinicians wishing to give comprehensive care to adolescent patients.

Psychosocial Assessment

A few questions should be asked to detect the adolescent who is having difficulty with peer relationships (“Do you have a best friend with whom you can share even the most personal secret?”), self-image (“Is there anything you would like to change about yourself?”), depression (“What do you see yourself doing 5 yr from now?”), school (“How are your grades this year compared with last year?”), personal decisions (“Are you feeling pressured to engage in any behavior for which you do not feel you are ready?”), and an eating disorder (“Do you ever feel that food controls you rather than vice versa?”). Bright Futures materials provide questions and patient encounter forms to structure the assessments that are available at their website (brightfutures.aap.org/index.html). The HEADS/SF/FIRST mnemonic, basic or expanded, can be useful in guiding the interview if encounter forms are not available (Table 106-4). Based on the assessments, appropriate counseling or referrals are recommended for more thorough probing or for in-depth interviewing.

Home. Space, privacy, frequent geographic moves, neighborhood.

Education/School. Frequent school changes, repetition of a grade/in each subject, teachers’ reports, vocational goals, after-school educational clubs (language, speech, math, etc.), learning disabilities.

Abuse. Physical, sexual, emotional, verbal abuse; parental discipline.

Drugs. Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, inhalants, “club drugs,” “rave” parties, others. Drug of choice, age at initiation, frequency, mode of intake, rituals, alone or with peers, quit methods, and number of attempts.

Safety. Seat belts, helmets, sports safety measures, hazardous activities, driving while intoxicated.

Sexuality/Sexual Identity. Reproductive health (use of contraceptives, presence of sexually transmitted infections, feelings, pregnancy)

Family and Friends. Family: Family constellation, genogram, single/married/separated/divorced/blended family, family occupations and shifts; history of addiction in 1st- and 2nd-degree relatives, parental attitude toward alcohol and drugs, parental rules; chronically ill physically or mentally challenged parent. Friends: peer cliques and configuration (“preppies,” “jocks,” “nerds,” “computer geeks,” cheerleaders), gang or cult affiliation.

Image. Height and weight perceptions, body musculature and physique, appearance (including dress, jewelry, tattoos, body piercing as fashion trends or other statement).

Recreation. Sleep, exercise, organized or unstructured sports, recreational activities (television, video games, computer games, Internet and chat rooms, church or community youth group activities [e.g., Boy/Girl Scouts; Big Brother/Sister groups, campus groups]). How many hours per day, days per week involved?

Spirituality and Connectedness. Use HOPE* or FICA† acronym; adherence, rituals, occult practices, community service or involvement.

Threats and Violence. Self-harm or harm to others, running away, cruelty to animals, guns, fights, arrests, stealing, fire setting, fights in school.

* HOPE: hope or security for the future; organized religion; personal spirituality and practices; effects on medical care and end of life issues.

† FICA: faith beliefs; importance and influence of faith; community support.

From Dias PJ: Adolescent substance abuse. Assessment in the office, Pediatr Clin North Am 49:269–300, 2002.

Physical Examination

Audiometry

Highly amplified music of the kind enjoyed by many adolescents may result in hearing loss (Chapter 629). A hearing screening is recommended by the Bright Futures guidelines for adolescents who are exposed to loud noises regularly, have had recurring ear infections, or report problems.

Blood Pressure Determination

Criteria for a diagnosis of hypertension are based on age-specific norms that increase with pubertal maturation (Chapter 439). An individual whose blood pressure exceeds the 95th percentile for his or her age is suspect for having hypertension, regardless of the absolute reading. Those adolescents with blood pressure between the 90th and 95th percentiles should receive appropriate counseling relative to weight and have a follow-up examination in 6 mo. Those with blood pressure above the 90th percentile should have their blood pressure measured on three separate occasions to determine the stability of the elevation before moving forward with an intervention strategy. The technique is important; false-positive results may be obtained if the cuff covers less than two thirds of the upper arm. The patient should be seated, and an average should be taken of the 2nd and 3rd consecutive readings, using the change rather than the disappearance as the diastolic pressure. Most adolescents with elevations of blood pressure have labile hypertension. If the blood pressure is below 2 standard deviations for age, anorexia nervosa and Addison disease should be considered.

Scrotum Examination

The peak incidence of germ cell tumors of the testes is in late adolescence and early adulthood. Palpation of the testes may have an immediate yield and should serve as a model for instruction of self-examination. Because varicoceles often appear during puberty, the examination also provides an opportunity to explain and reassure the patient about this entity (Chapter 539).

Laboratory Testing

The increased incidence of iron-deficiency anemia after menarche mandates the performance of a hematocrit annually in young women with moderate to heavy menses. The reference standard for this test changes with progression of puberty, as estrogen suppresses erythropoietin (Chapter 440). Populations with nutritional risk should also have the hematocrit monitored. Androgens have the opposite effect, causing the hematocrit to rise during male puberty; Sexual Maturity Rating 1 males (Chapter 104) have an average hematocrit of 39%, whereas those who have completed puberty (Sexual Maturity Rating 5; Chapter 104) have an average value of 43%. Tuberculosis testing on an annual basis is important in adolescents with risk factors, such as an adolescent with HIV, living in the household with someone with HIV, the incarcerated adolescent, or those with other risk factors, because puberty has been shown to activate this disease in those not previously treated. Hepatitis C virus screening should be offered to adolescents who report risk factors, such as injection drug use, received blood products or organ donation before 1992, long-term hemodialysis, or high prevalence setting (i.e., correctional facilities or STI clinics).

Sexually active adolescents should undergo screening for STIs regardless of symptoms (Chapter 114). There are clear indications for chlamydia and gonorrhea screening of females 25 yr old and younger, but less sufficient evidence to support routine screening in young men. Screening young men is a clinical option and with newer noninvasive testing. HIV screening should be discussed with those who are sexually active, especially men who have sex with men, and injection drug users. Syphilis screening is recommended for pregnant adolescents and those at increased risk of infection. For sexually active females, the guidelines for Pap smears for cervical cancer screening suggest that annual screening can be delayed safely up to 3 yr after the onset of sexual activity or age 21 yr, whichever is earlier; HPV DNA testing should not be used routinely for females 29 yr and younger since the results would not influence management.

ACOG Committee on Gynecological Practice. ACOG committee opinion No. 431: routine pelvic examination and cervical cytology screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1190-1193.

Duncan PM, Duncan ED, Swanson J. Bright futures: the screening table recommendations. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37:152-158.

Myers E, Huh WK, Wright JD, et al. The current and future role of screening in the era of HPV vaccination. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:S31-S39.

Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee, American College of Physicians. Screening for HIV in health care settings: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians and HIV Medicine Association. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:125-131.

Williams SB, O’Connor EA, Eder M, et al. Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e716-e735.

106.3 Health Enhancement

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Achieving quality health services for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1263-1270.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence and Committee on Child Health Financing. Underinsurance of adolescents: recommendations for improved coverage of preventive, reproductive, and behavioral health care services. Pediatrics. 2009;123:191-196.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family. The future of pediatrics: mental health competencies for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124:410-421.

Broder KR, Cohn AC, Schwartz B, et al. Adolescent immunizations and other clinical preventive services: a needle and a hook? Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 1):S25-S34.

English A, Ford CA. The HIPAA privacy rule and adolescents: legal questions and clinical challenges. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:80-86.

Fishbein DB, Broder KR, Markowitz L, et al. New, and some not-so-new, vaccines for adolescents and diseases they prevent. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S5-S14.

Ford CA, English A, Davenport AF, et al. Increasing adolescent vaccination: barriers and strategies in the context of policy, legal, and financial issues. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:568-574.

Ford CA, English A, Sigman G. Confidential healthcare for adolescents: a position paper for the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:1-8.

Hagan JFJr, Shaw JS, Duncan P, editors. Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

Kreipe RE. Introduction to interviewing: the art of communication with adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2008;10:1-17.

Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, et al. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:8-24.

Society for Adolescent Medicine. Access to health care for adolescents and young adults: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:342-344.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2008. Recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (AHRQ Publication No. 08-05122) (website) www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm Accessed April 16, 2010

106.4 Transitioning to Adult Care

Given such potentially daunting obstacles, several models have been developed, although largely untested, that describe key elements to the transition process (Table 106-5). Most authors suggest an early start sometime during mid-adolescence although this timeframe should be flexible depending on the developmental stage of the patient. One person, usually the primary care provider, should take the lead for working with the patient and family on drawing up the transition plan. Optimally the plan should be written down and revised periodically with input from all key parties. One of the key aspects of the transition process is skills training for the adolescent in communication, self-advocacy, and self-care. Also important is support for transition to the adult world beyond health care that includes attention to the educational, psychosocial, and vocational needs of the patient. Crucial for effective communication with the adult service is a comprehensive and portable medical summary of the patient’s condition and treatment. Last, as mentioned earlier, it is crucial to ensure continuity of care by ensuring uninterrupted insurance coverage. The ultimate goal is to help these young people maximize their potential as their transition to adulthood.

Table 106-5 KEY ELEMENTS OF TRANSITIONAL CARE

Adapted from McDonagh JE, Viner RM: Lost in transition? Between paediatric and adult services, BMJ 332:435–436, 2006.

Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:403-409.

Knauth A, Verstappen A, Reiss J, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care of the young adult with complex heart disease. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:619-629.

McDonagh JE, Viner RM. Lost in transition? Between paediatric and adult services. BMJ. 2006;332:435-436.

Rosen D, Blum RW, Britto M, et al. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions. Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:309-311.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines needed by teens and college students. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/schedules/teen-schedule.htm. Accessed April 16, 2010

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

Morreale MC, Kapphahn CJ, Elster AB, et al. Access to health care for adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:342-344.

Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, et al. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:8-24.

MacKay AP, Duran C. Adolescent health in the United States, 2007. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2007. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/adolescent2007.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2010