104 Delirium and Dementia

• Delirium is a medical emergency (not a psychiatric emergency) that can be superimposed on a chronic condition such as dementia.

• Because delirium is associated with high mortality, especially in the elderly, early recognition and treatment are essential.

• A systematic, detailed evaluation, including cognitive assessment, is critical to the diagnosis of delirium and differentiation of delirium from dementia.

• Hypoglycemia and hypoxia are easily identified and reversible causes of delirium.

• Infections and medication effects are common causes of delirium, and the management plan must focus on identifying and treating these processes.

Epidemiology

Altered mental status affects 5% to 10% of patients seen in the emergency department (ED) and in up to 30% of the older population.1 Delirium and dementia account for a significant proportion of the altered mental status. Hustey and Meldon reported that of 78 ED patients with changes in mental status, 62% had cognitive impairment without delirium and the remaining 38% had delirium.2 In a study at a single tertiary care center, it was found that emergency physicians (EPs) missed the diagnosis of delirium in up to 75% of patients older than 65 years; either the condition was misdiagnosed or the patients were discharged home.3 Some studies suggest a mortality rate as high as 9% in patients who are admitted to the hospital because of altered mental status. One study found that patients who were discharged home with unrecognized delirium had a mortality of 30.8% at 6 months.4 The challenge for the EP, who has not generally seen the patient previously, is recognizing delirium—an acute process—when it is superimposed on dementia—a chronic process. Therefore, a systematic approach to ED evaluation is necessary.

Alzheimer dementia is the most common form of dementia in adults (occurring in 50% to 60% of patients), followed by vascular dementia (15% to 25%), Lewy body dementia (5%), and Parkinson dementia (5%).5,6

Delirium

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of delirium is not known, but it is believed to arise from an imbalance of neurotransmitters at the cortical and subcortical levels. The principal neurotransmitters implicated in causing delirium include dopamine, an excitatory neurotransmitter, and acetylcholine and γ-aminobutyric acid, inhibiting neurotransmitters.7 Physiologic stressors such as infection, medications, and metabolic disturbances can alter the balance of the levels of neurotransmitters and lead to changes in cognition and attention. Inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and histamines are thought to be involved as well.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

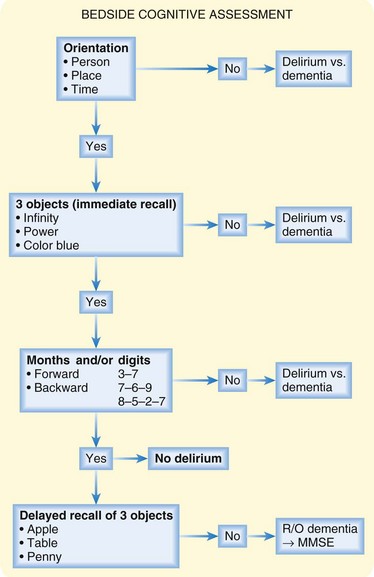

Delirium is a syndrome and not a specific disease; therefore, identifying the underlying cause requires a comprehensive approach that includes a medical and family history, physical examination, bedside cognitive assessment, and diagnostic testing. The confusion assessment method is a useful tool to screen for delirium in the medical setting.8 In an uncooperative or severely confused patient, information obtained from emergency medical service personnel and the patient’s family, personal items brought in with the patient, and a detailed physical examination with close attention to vital signs are important. Figure 104.1 provides a structured approach to assessing cognition at the bedside; patients who are oriented with immediate recall and the ability to sustain attention and recite months or digits in reverse but no delayed recall are unlikely to have delirium and should be suspected of having dementia.8 The EP should consider all possible reversible medical causes of delirium so that treatment can be initiated as soon as possible (Box 104.1).

Box 104.1 Causes of Delirium

Drug Toxicity

Many commonly prescribed medications can cause delirium as a result of improper dosing, change in metabolism, intentional overdose, and drug-drug interactions (Box 104.2).9 Family members or the patient’s personal physician may be able to provide valuable information about recent changes in medication dosages or the addition of new medications.

Cerebrovascular Disorders

Delirium is a common complication after an acute stroke and is reported in up to 48% of patients.10 Despite case reports of delirium being the primary manifestation of an acute stroke,11 it is more frequently reported as a sequela of the event. Delirium has been associated with left-sided infarcts and thalamic and caudate nucleus strokes. Delirium after stroke has been linked to longer hospital stay and increased mortality.

Endocrine Disorders

Patients with endocrine disorders such as hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, Cushing syndrome, and hyperparathyroidism may have altered mental status when seen initially in the ED.12 Delirium is more common with severe manifestations of these diseases, as in the case of thyroid storm and myxedema coma. Abnormalities in vital signs, such as tachycardia and fever in thyroid storm and bradycardia and hypotension in myxedema coma, may be the only initial clues to the diagnosis.

Chemical Exposure

Delirium may be the initial symptom in patients exposed to a chemical weapon or contaminated environment. History of the exposure is important, but the patient often displays confusion and no history is available. If chemical exposure is suspected, the patient must be brought to the proper decontamination area immediately. Universal precautions should be practiced, as well as use of a proper-level hazmat suit. The patient should be stabilized and evaluated for findings on examination and vital signs suggesting the cause of the contamination and thus the antidote (Box 104.3).

Central Nervous System Disease

Absence seizures, seen primarily in children 5 to 10 years of age, are characterized by acute-onset altered mental status without motor activity. The seizure episodes typically last for seconds and resolve without a postictal state. Complex partial seizures can also be accompanied by an acute change in mental status. Patients with nonconvulsive status epilepticus (absence or complex partial) may have a change in mental status that can vary in intensity and duration.13 Nonconvulsive status can occur in patients of all ages and without any previous history of a seizure disorder. Clinical findings vary from a minor change in mental status to full-blown psychotic or comatose states. The hallmark of nonconvulsive status epilepticus is a change in mental status that occurs in the absence of motor activity and is associated with characteristic electroencephalographic changes. Motor activity, when present, is subtle and in the form of mild twitching of the lips or the upper or lower extremities, but no clear tonic-clonic activity is present.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

If delirium is excluded after a thorough work-up of a patient with confusion, other causes of altered cognition should be considered. An elderly patient with newly recognized or worsening dementia may arrive at the ED with an acute decline in consciousness. Family members may recall changes in memory and function over a longer period, thus suggesting dementia rather than delirium (Table 104.1).

Table 104.1 Clinical Characteristics of Delirium versus Dementia

| CHARACTERISTIC | DELIRIUM | DEMENTIA |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Acute | Insidious |

| Course | Fluctuating | Progressive |

| Orientation | No | Yes |

| Attention | Impaired | Intact |

| Cognitive function | Impaired* | Impaired |

| Speech | Pressured or unintelligible | Normal |

* Some of the cognitive impairments reported in patients with delirium may actually be due to inattention.

First-time manifestations of psychiatric disorders or exacerbation of underlying psychiatric disease can often be confused with delirium as a result of their similar characteristics. Because patients with psychiatric illness can exhibit delirium, medical and reversible causes of the confusion must be excluded before transfer of care to a psychiatrist14 (see the Priority Actions box “Tests Useful in the Diagnosis of Delirium”).

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Tests Useful in the Diagnosis of Delirium

Endocrine Disorders

Treatment

Pharmacologic management of agitation is sometimes necessary when a patient with delirium is a danger to self or others or if the agitation is impeding medical evaluation and management. Current pharmacologic options include typical and atypical antipsychotic agents and benzodiazepines.15 Both droperidol and haloperidol are generally safe and effective and cause less respiratory depression than benzodiazepines do. However, the benzodiazepines, midazolam or lorazepam, may be preferable in particular clinical scenarios such as drug withdrawal or overdose. It is important to remember to reduce dosing in elderly patients because they have altered pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics. There is currently no good literature to support the use of atypical antipsychotics in the acute management of delirium.

Dementia

Pathophysiology

At the anatomic level, Alzheimer dementia is characterized by atrophy of both cortical and subcortical structures, which is seen most prominently in the hippocampus and temporal cortex. Histologic examination reveals an accumulation of extracellular amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that attract inflammatory mediators and impede delivery of neurotransmitters along the axons, respectively. Deficiencies in the neurotransmitters acetylcholine and norepinephrine are also thought to be responsible for the dementia in Alzheimer disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical characteristics of the types of dementia are presented in Table 104.2.16

Table 104.2 Clinical and Pathophysiologic Symptoms and Signs in Types of Dementia

| DISORDER | SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS | |

|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL | PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC | |

| Alzheimer disease | Gradual and continuing functional decline not explained by another cause of dementia | Amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, hippocampal and temporal atrophy |

| Vascular dementia | Sudden onset, focal neurologic findings, stepwise deterioration | Multiple infarcts |

| Lewy body dementia | Visual hallucinations, fluctuating cognition, mild parkinsonism seen less than 1 yr before dementia | Lewy bodies, Lewy neuritis |

| Parkinson dementia | Extrapyramidal signs, visual hallucinations, fluctuating cognition | Lewy bodies, Lewy neuritis |

| Frontotemporal dementia (Pick disease) | Personality changes, restlessness, disinhibition, impulsiveness, ataxia, parkinsonism | Pick bodies, frontal and temporal atrophy |

| Infectious dementia (Creutzfeldt-Jakob) | Visual disturbances, ataxia, myoclonus, progressive dementia | Prion protein accumulation, spongiform change of brain |

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Alzheimer disease is characterized by a gradual onset of dementia, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (Box 104.4), with continuous functional decline. The cognitive impairment seen in Alzheimer disease is not explained by other causes of dementia. Most patients in the ED with Alzheimer disease will already carry the diagnosis and probably have an associated complication such as infection or exacerbation of the dementia.

Box 104.4 DSM-IV Criteria for Dementia

1. Memory impairment (inability to learn new information or to recall previously learned information)

2. At least one of the following:

3. The deficits listed above significantly impair social or occupational functioning and are a significant decline from a previous level of functioning.

4. The deficits do not occur exclusively during the course of an episode of delirium.

5. The deficits are not better accounted for by another disorder.

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

Treatment

Cholinesterase inhibitors are often used in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer-type dementia; vitamin E has also been recommended to slow the progression of Alzheimer dementia.17 Cholinesterase inhibitors have been recommended to improve quality of life and cognitive function. However, despite the frequent use of these medications, the literature on the benefit of cholinesterase inhibitors remains controversial.18

American Academy of Neurology. Detection, diagnosis and management of dementia: AAN guideline summary. Available at http://www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/dementia_guideline.pdf, 2011. Downloaded January 2

American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients with altered mental status. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:251–281.

Han J, Wilson A, Ely EW. Delirium in the older emergency department patient: a quiet epidemic. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:611–631.

Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:193–200.

Koita J, Riggio S, Jagoda A. The mental status examination in emergency practice. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:439–451.

1 Han J, Wilson A, Ely EW. Delirium in the older emergency department patient: a quiet epidemic. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:611–631.

2 Hustey F, Meldon S. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:248–253.

3 Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:193–200.

4 Kakuma R, Galbaud du Fort G, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:443–450.

5 Dugu M, Neugroschl J, Sewell M, et al. Review of dementia. Mt Sinai J Med. 2003;70:45–53.

6 Tolosa E, Wenning G, Poewe W. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:75–86.

7 Pandharipande P, Jackson J, Ely W. Delirium: acute cognitive dysfunction in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:360–368.

8 Koita J, Riggio S, Jagoda A. The mental status examination in emergency practice. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:439–451.

9 Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens C. An approach to drug-induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:388–393.

10 McManus J, Pathansali R, Stewart R, et al. Delirium post stroke. Age Ageing. 2007;36:613–618.

11 Vatsavayi V, Malhotra S, Franco K. Agitated delirium with posterior cerebral artery infarction. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:263–266.

12 Casaletto J. A review of endocrine and metabolic causes of altered level of consciousness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:633–662.

13 Treiman D, Walker M. Treatment of seizure emergencies: convulsive and non-convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2006;68(Suppl. 1):S7–S82.

14 Reeves R, Pendarvis E, Kimble R. Unrecognized medical emergencies admitted to psychiatric units. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:390–393.

15 American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients with altered mental status. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:251–281.

16 Love S. Neuropathological investigation of dementia: a guide for neurologists. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:8–14.

17 American Academy of Neurology. Detection, diagnosis and management of dementia: AAN guideline summary. Available at http://www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/dementia_guideline.pdf Downloaded January 2, 2011

18 Kaduszkiewicz H, Zimmerman T, Beck-Bornholdt H, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for patients with Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review of randomized clinical trials. BMJ. 2005;331:321–323.

scan or CT angiography of the chest, D-dimer

scan or CT angiography of the chest, D-dimer , ventilation-perfusion.

, ventilation-perfusion.