Chapter 4 Delirium

Delirium is by far the most common behavioral disorder in a medical-surgical setting. In general hospitals, the prevalence ranges from 11% to 33% on admission. The incidence ranges between 6% and 56% of hospitalized patients, 15% to 53% postoperatively in elderly patients, and 80% or more of intensive care unit (ICU) patients (Fong, Tulebaev, and Inouye, 2009; Michaud et al., 2007). The consequences of delirium are serious: They include prolonged hospitalizations, increased mortality, high rates of discharges to other institutions, severe impact on caregivers and spouses, and between $38 billion and $152 billion annually in direct healthcare costs in the United States (Breitbart, Gibson, and Tremblay, 2002; Fong, Tulebaev, and Inouye, 2009; Inouye et al., 1999).

Physicians have known about this disorder since antiquity. Hippocrates referred to it as phrenitis, the origin of our word frenzy. In the 1st century ad, Celsus introduced the term delirium, from the Latin for “out of furrow,” meaning derailment of the mind, and Galen observed that delirium was often due to physical diseases that affected the mind “sympathetically.” In the 19th century, Gowers recognized that these patients could be either lethargic or hyperactive. Bonhoeffer, in his classification of organic behavioral disorders, established that delirium is associated with clouding of consciousness. Finally, Engel and Romano (1959) described alpha slowing with delta and theta intrusions on electroencephalograms (EEGs) and correlated these changes with clinical severity. They noted that treating the medical cause resulted in reversal of both the clinical and EEG changes of delirium.

Despite this long history, physicians, nurses, and other clinicians often fail to diagnose delirium (Cole, 2004; Inouye et al., 2001), and up to two-thirds of delirium cases go unidentified (Inouye, 2004). Healthcare providers often miss this syndrome more from lack of recognition than misdiagnosis. The elderly in particular may have a “quieter,” more subtle presentation of delirium that may evade detection. Adding to the confusion about delirium are the many terms used to describe this disorder: acute confusional state, acute organic syndrome, acute brain failure, acute brain syndrome, acute cerebral insufficiency, exogenous psychosis, metabolic encephalopathy, organic psychosis, ICU psychosis, toxic encephalopathy, toxic psychosis, and others.

Clinical Characteristics

The essential elements of delirium are summarized in Boxes 4.1 and 4.2. Among the proposed American Psychiatric Association’s criteria (DSM-V Proposed Revision, 2013) for this disorder is a disturbance that develops over a short period of time; tends to fluctuate; and impairs awareness, attention, and other areas of cognition. In general, awareness, attention, and cognition fluctuate over the course of a day. Furthermore, delirious patients have disorganized thinking and an altered level of consciousness, perceptual disturbances, disturbance of the sleep/wake cycle, increased or decreased psychomotor activity, disorientation, and memory impairment. Other cognitive, behavioral, and emotional disturbances may also occur as part of the spectrum of delirium. Delirium can be summarized into the 10 clinical characteristics that follow.

Box 4.1 Clinical Characteristics of Delirium

Box 4.2

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition, Proposed Revision, Criteria for Delirium due to a General Medical Condition

A. Disturbance in level of awareness and reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention

B. A change in cognition (such as deficits in orientation, executive ability, language, visuoperception, learning, and memory):

C. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is caused by the direct physiological consequences of a general medical condition

D. The disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to a few days) and tends to fluctuate in severity during the course of a day

Modified from American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth ed., proposed revision. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.

Cognitive and Related Abnormalities

Other Cognitive Deficits

Writing disturbance may be the most sensitive language abnormality in delirium. The most salient characteristics are abnormalities in the mechanics of writing: The formation of letters and words is indistinct, and words and sentences sprawl in different directions (Fig. 4.1). There is a reluctance to write, and there are motor impairments (e.g., tremors, micrographia) and spatial disorders (e.g., misalignment, leaving insufficient space for the writing sample). Sometimes the writing shows perseverations of loops or aspects of the writing. Spelling and syntax are also disturbed, with spelling errors particularly involving consonants, small grammatical words (prepositions and conjunctions), and the last letters of words. Writing is easily disrupted in these disorders, possibly because it depends on multiple components and is the least used language function.

Pathophysiology

Several brain areas involved in attention are particularly disturbed in delirium. Dysfunction of the anterior cingulate cortex is involved in disturbances of the management of attention (Reischies et al., 2005). Other areas include the bilateral or right prefrontal cortex in attentional maintenance and executive control, the temporoparietal junction region in disengaging and shifting attention, the thalamus in engaging attention, and the upper brainstem structures in moving the focus of attention. The thalamic nuclei are uniquely positioned to screen incoming sensory information, and small lesions in the thalamus may cause delirium. In addition, there is evidence that the right hemisphere is dominant for attention. Cortical blood flow studies suggest that right hemisphere cortical areas and their limbic connections are the “attentional gate” for sensory input through feedback to the reticular nucleus of the thalamus.

Another explanation for delirium is alterations in neurotransmitters, particularly a cholinergic-dopaminergic imbalance. There is extensive evidence for a cholinergic deficit in delirium (Inouye, 2006). Anticholinergic agents can induce the clinical and EEG changes of delirium, which are reversible with the administration of cholinergic medications such as physostigmine. The beneficial effects of donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine—acetylcholinesterase-inhibitor medications used for Alzheimer disease—may be partly due to an activating or attention-enhancing role. Moreover, cholinergic neurons project from the pons and the basal forebrain to the cortex and make cortical neurons more responsive to other inputs. A decrease in acetylcholine results in decreased perfusion in the frontal cortex. Hypoglycemia, hypoxia, and other metabolic changes may differentially affect acetylcholine-mediated functions. Other neurotransmitters may be involved in delirium, including dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, γ-aminobutyric acid, glutamine, opiates, and histamine. Dopamine has an inhibitory effect on the release of acetylcholine, hence the delirium-producing effects of l-dopa and other antiparkinsonism medications (Trzepacz and van der Mast, 2002). Opiates may induce the effects by increasing dopamine and glutamate activity. Recently, polymorphisms in genes coding for a dopamine transporter and two dopamine receptors have been associated with the development of delirium (van Munster et al., 2010).

Inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins, interferon, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), may contribute to delirium by altering blood-brain barrier permeability and further affecting neurotransmission (Cole, 2004; Fong et al., 2009; Inouye, 2006). The combination of inflammatory mediators and dysregulation of the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary axis may lead to exacerbation or prolongation of delirium (Maclullich et al., 2008). Finally, secretion of melatonin, a hormone integral to circadian rhythm and the sleep/wake cycle, may be abnormal in delirious patients compared to those without delirium (van Munster, de Rooij, and Korevaar, 2009).

Diagnosis

Predisposing and Precipitating Factors

The greater the number of predisposing factors, the fewer or milder are the precipitating factors needed to result in delirium (Anderson, 2005) (Box 4.3). Four factors independently predispose to delirium: vision impairments (<20/70 binocular), severity of illness, cognitive impairment, and dehydration (high ratio of blood urea to creatinine) (Inouye, 2006). Among these, cognitive impairment or dementia is worth emphasizing. Elderly patients with dementia are five times more likely to develop delirium than those without dementia (Elie et al., 1998). Patients with dementia may develop delirium after minor medication changes or other relatively insignificant precipitating factors (Inouye, 2006). Moreover, premorbid impairment in executive functions may be independently associated with greater risk of developing delirium (Rudolph et al., 2006). Other important predisposing factors for delirium are advanced age, especially older than 80 years, and the presence of chronic medical illnesses (Johnson, 2001). Many of these elderly patients predisposed to delirium have cerebral atrophy or white matter and basal ganglia ischemic changes on neuroimaging. Additional predisposing factors are the degree of physical impairment, hip and other bone fractures, serum sodium changes, infections and fevers, and the use of multiple drugs, particularly those with narcotic, anticholinergic, or psychoactive properties. The predisposing factors for delirium are additive, each new factor increasing the risk considerably. Moreover, frail elderly patients often have multiple predisposing factors, the most common being functional dependency, multiple medical comorbidities, depression, and polypharmacy (Laurila et al., 2008).

Box 4.3 Predisposing and Precipitating Factors for Delirium

Elderly, especially 80 years or older

Dementia, cognitive impairment, or other brain disorder

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances and dehydration

Other metabolic disturbance, especially elevated BUN level or hepatic insufficiency

Number and severity of medical illnesses including cancer

Infections, especially urinary tract, pulmonary, and AIDS

Malnutrition, low serum albumin level

Cardiorespiratory failure or hypoxemia

Prior stroke or other nondementia brain disorder

Polypharmacy and use of analgesics, psychoactive drugs, or anticholinergics

Drug abuse, alcohol or sedative dependency

Sensory impairment, especially visual

Sensory overstimulation and “ICU psychosis”

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; ICU, intensive care unit.

In most cases, the cause of delirium is multifactorial, resulting from the interaction between patient-specific predisposing factors and multiple precipitating factors (Inouye and Charpentier, 1996; Laurila et al., 2008). Five specific factors that can independently precipitate delirium are use of physical restraints, malnutrition or weight loss (albumin levels less than 30 g/L), use of indwelling bladder catheters, adding more than three medications within a 24-hour period, and an iatrogenic medical complication (Inouye and Charpentier, 1996). Other precipitating factors for incident delirium after hospitalization include electrolyte disturbances (hyponatremia, hypercalcemia, etc.), major organ system disease, occult respiratory failure, occult infection, pain, specific medications such as sedative-hypnotics or histamine-2 blockers, sleep disturbances, and alterations in the environment. Novel situations and unfamiliar surroundings contribute to sensory overstimulation in the elderly, and sensory overload may be a factor in producing “ICU psychosis.” Ultimately, delirium occurs in patients from a synergistic interaction of predisposing factors with precipitating factors.

In addition to the risk factors already discussed, heritability of delirium is a new area of investigation. The presence of genes such as apolipoprotein E (APOE), dopamine receptor genes DRD2 and DRD3, and the dopamine transporter gene, SLC6A3, are possible pathophysiological vulnerabilities for delirium (van Munster et al., 2009; van Munster et al., 2010). Despite conflicting data, there is evidence for an association between APOE ε4 carriers and a longer duration of delirium (van Munster et al., 2009). Polymorphisms in SLC6A3 and DRD2 have occurred in association with delirium from alcohol and in elderly delirious patients with hip fractures (van Munster et al., 2009; van Munster et al., 2010).

Diagnostic Scales and Criteria

The usual mental status scales and tests may not help in differentiating delirium from dementia and other cognitive disturbances. Specific criteria and scales are available for the diagnosis of delirium. Foremost among these are the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V, Proposed Revision, 2013) criteria for delirium (see Box 4.2). The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a widely used instrument for screening for and diagnosing delirium (Ely et al., 2001) (Box 4.4). The Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98), a revision of the earlier Delirium Rating Scale (DRS), is a 16-item scale with 13 severity items and three diagnostic items that reliably distinguish delirium from dementia, depression, and schizophrenia (Trzepacz et al., 2001). Both the CAM and the DRS-R-98 are best used in combination with a cognitive test (Adamis et al., 2010). The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) is a 10-item scale designed to quantify the severity of delirium in medically ill patients (Breitbart et al., 1997). While it may also be useful as a diagnostic tool, it is best used after the initial delirium diagnosis is made (Adamis et al., 2010). The Delirium Symptom Interview is also a valuable instrument but may not distinguish delirium from dementia. The Neelon and Champagne (NEECHAM) Confusion Scale (Neelon et al., 1996) is an easily administered screening tool widely used in the nursing community. It combines behavioral and physiological signs of delirium, but it has been suggested that the NEECHAM measures acute confusion rather than delirium (Adamis et al., 2010). The diagnosis of delirium is facilitated by the use of the CAM, DRS-R-98, MDAS, the Delirium Symptom Interview, the Delirium Index (McCusker et al., 2004), or the NEECHAM, along with the history from collateral sources such as family and nursing notes, a mental status examination focusing on attention, and specific tests such as a writing sample.

Box 4.4

Confusion Assessment Method

1. Acute onset and fluctuating course (mental status changes from hours to days)

2. Difficulty in focusing (easily distracted, unable to follow interview)

3. Disorganized thinking (rambling, irrelevant conversation)

4. Altered level of consciousness (from hyperalert to decreased arousal)

A positive confusion assessment method (CAM) test for delirium requires items 1 and 2 plus either item 3 or item 4 (Inouye, 2006; supplementary material).

Laboratory Tests

Despite false-positive and false-negative rates on single tracings (Inouye, 2006), EEG changes virtually always accompany delirium when several EEGs are obtained over time (see Chapter 32A). Disorganization of the usual cerebral rhythms and generalized slowing are the most common changes, as illustrated in Romano and Engel’s classic paper (1944). The mean EEG frequency or degree of slowing correlates with the degree of delirium. Both hypoactive and hyperactive subtypes of delirium have similar EEG slowing; however, predominant low-voltage fast activity is also present on withdrawal from sedative drugs or alcohol. Additional EEG patterns from intracranial causes of delirium include focal slowing, asymmetric delta activity, and paroxysmal discharges (spikes, sharp waves, and spike-wave complexes). Periodic complexes such as triphasic waves and periodic lateralizing epileptiform discharges may help in the differential diagnosis (see Chapter 32A). EEGs are of value in deciding whether confusional behavior may be due to an intracranial cause, in making the diagnosis of delirium in patients with unclear behavior, in evaluating demented patients who might have a superimposed delirium, in differentiating delirium from schizophrenia and other primary psychiatric states, and in following the course of delirium over time.

Since most cases of delirium are due to medical conditions, lumbar puncture and neuroimaging are needed in only a minority of delirious patients (Inouye, 2006). The need for a lumbar puncture, however, deserves special comment. This valuable test, which is often neglected in the evaluation of delirious patients, should be performed as part of the workup when the cause is uncertain. The lumbar puncture should be preceded by a computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain, especially if there are focal neurological findings or suspicions of increased ICP, a space-occupying lesion, or head trauma. The yield of functional imaging is variable, showing global increased metabolism in patients with delirium tremens and global decreased metabolism or focal frontal hypoactivity in many other delirious patients.

Differential Diagnosis

Common Causes of Delirium

The following discussion is a selective commentary that illustrates some basic principles and helps organize the approach to working through the large differential diagnosis. Almost any sufficiently severe medical or surgical illness can cause delirium, and the best advice is to follow all available diagnostic leads (Table 4.1). (For further discussion of individual entities, the reader should refer to corresponding chapters in this book.) The confusion-inducing effects of these disturbances are additive, and there may be more than one causal factor, the individual contribution of which cannot be elucidated. Nearly half of elderly patients with delirium have more than one cause of their disorder, and clinicians should not stop looking for causes when a single one is found. Of the causes for delirium, the most common among the elderly are metabolic disturbances, infection, stroke, and drugs, particularly anticholinergic and narcotic medications. The most common causes among the young are drug abuse and alcohol withdrawal.

| Metabolic disorders | Cardiac encephalopathy, hepatic encephalopathy, uremia, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, hyponatremia, hypo-/hypercalcemia, hypo-/hypermagnesemia, other electrolyte disturbances, acidosis, hyperosmolar coma, endocrinopathies (thyroid, parathyroid, pituitary), porphyria, vitamin deficiencies (thiamine, vitamin B12, nicotinic acid, folic acid), toxic and industrial exposures (carbon monoxide, organic solvent, lead, manganese, mercury, carbon disulfide, heavy metals) |

| Drug related | Withdrawal syndromes (alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, other), amphetamines, cocaine, coffee, phencyclidine, hallucinogens, inhalants, meperidine and other narcotics, antiparkinsonism drugs, sedative-hypnotics, corticosteroids, anticholinergic and antihistaminic drugs, cardiovascular agents (beta-blockers, clonidine, digoxin), psychotropics (phenothiazines, clozapine, lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, trazodone), 5-fluorouracil and cytotoxic antineoplastics, anticonvulsants (phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproate), cimetidine, disulfiram, ergot alkaloids, salicylates, methyldopa, and selected antiinfectious agents (acyclovir, amphotericin B, cephalexin, chloroquine, isoniazid, rifampin) |

| Infections | Meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, neurosyphilis, Lyme neuroborreliosis, cerebritis, systemic infections with septicemia |

| Neurological | Strokes, epilepsy, head injury, hypertensive encephalopathy, brain tumors, migraine, other neurovascular disorders |

| Perioperative | Specific surgeries (cardiac, orthopedic, ophthalmological), anesthetic and drug effects, hypoxia and anemia, hyperventilation, fluid and electrolyte disturbances, hypotension, embolism, infection or sepsis, pain, fragmented sleep, sensory deprivation or overload |

| Miscellaneous | Cerebral vasculitides, paraneoplastic and limbic encephalitis, hyperviscosity syndromes, trauma, cardiovascular, dehydration, sensory deprivation |

Metabolic Disturbances

Metabolic disturbances are the most common causes of delirium (see Chapter 49, Chapter 55, Chapter 56, Chapter 57, Chapter 58 ). Fortunately, the examination and routine laboratory tests screen for most acquired metabolic disturbances that might be encountered. Because of the potential for life-threatening or permanent damage, some of these conditions—particularly hypoxia and hypoglycemia—must be considered immediately. Also consider dehydration, fluid and electrolyte disorders, and disturbances of calcium and magnesium. The rapidity of change in an electrolyte level may be as important a factor as its absolute value for the development of delirium. For example, some people tolerate chronic sodium levels of 115 mEq/L or less, but a rapid fall to this level can precipitate delirium, seizures, or even central pontine myelinolysis, particularly if the correction of hyponatremia is too rapid. Hypoxia from low cardiac output, respiratory insufficiency, or other causes is another common source of delirium. A cardiac encephalopathy may ensue from heart failure, increased venous pressure transmitted to the dural venous sinuses and veins, and increased ICP (Caplan, 2006). Also consider other major organ failures such as liver and kidney failure, including the possibility of unusual causes such as undetected portocaval shunting or acute pancreatitis with the release of lipases. Delirium due to endocrine dysfunction often has prominent affective symptoms such as hyperthyroidism and Cushing syndrome. Delirium occasionally results from toxins including industrial agents, pollutants, and heavy metals such as arsenic, bismuth, gold, lead, mercury, thallium, and zinc. Other considerations are inborn errors of metabolism such as acute intermittent porphyria. Finally, it is particularly important to consider thiamine deficiency. In alcoholics and others at risk, thiamine must be given immediately to avoid precipitating Wernicke encephalopathy with the administration of glucose.

Drugs

Drug intoxication and drug withdrawal are among the most common causes of delirium. Approximately 50% of patients over the age of 65 take five or more chronic medications daily, and medications contribute to delirium in up to 39% of these patients (Inouye and Charpentier, 1996). Drug effects are additive, and drugs that are especially likely to cause delirium are those with anticholinergic properties, including many over-the-counter cold preparations, antihistamines, antidepressants, and neuroleptics. Patients with anticholinergic intoxication present “hot as a hare, blind as a bat, dry as a bone, red as a beet, and mad as a hatter,” reflecting fever, dilated pupils, dry mouth, flushing, and delirium. Other important groups of drugs associated with delirium, especially in the elderly, are sedative-hypnotics such as long-acting benzodiazepines, narcotic analgesics and meperidine, and histamine-2 receptor blockers. Antiparkinsonism drugs result in confusion with prominent hallucinations and delusions in patients with Parkinson disease who are particularly susceptible. Corticosteroid psychosis may develop in patients taking the equivalent of 40 mg/day or more of prednisone. The behavioral effects of corticosteroids often begin with euphoria and hypomania and proceed to a hyperactive delirium. Any drug administered intrathecally, such as metrizamide, is prone to induce confusional behavior. Drug withdrawal syndromes can be caused by many agents including barbiturates and other minor tranquilizers, sedative-hypnotics, amphetamines, cocaine or “crack,” and alcohol. Delirium tremens begins 72 to 96 hours after alcohol withdrawal, with profound agitation, tremulousness, diaphoresis, tachycardia, fever, and frightening visual hallucinations.

Infections

Infections and fevers often produce delirium. The main offenders are urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and septicemia. In a sporadic encephalitis or meningoencephalitis, important causal considerations are herpes simplex virus, Lyme disease, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (see Chapter 53A). Patients with AIDS may be delirious because of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) itself or because of an opportunistic infection. Immunocompromised patients are at greater risk of infection, and any suspicion of infection should prompt culture of urine, sputum, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid.

Strokes

Delirium can be the nonspecific consequence of any acute stroke, but most postinfarct confusion usually resolves in 24 to 48 hours (see Chapter 51B). Sustained delirium can result from specific strokes, including right middle cerebral artery infarcts affecting prefrontal and posterior parietal areas, and posterior cerebral artery infarcts resulting in either bilateral or left-sided occipitotemporal lesions (fusiform gyrus). The latter lesions can lead to agitation, visual field changes, and even Anton syndrome (see Chapter 14). Delirium may also follow occlusion of the anterior cerebral artery or rupture of an anterior communicating artery aneurysm with involvement of the anterior cingulate gyrus and septal region. Thalamic or posterior parietal cortex strokes may present with severe delirium, even with small lesions.

Postoperative Causes

The cause of delirium in postoperative patients is often multifactorial (Robinson et al., 2009; Winawer, 2001). Predisposing factors to postoperative delirium include age older than 70 years, preexisting CNS disorders such as dementia and Parkinson disease, severe underlying medical conditions, a history of alcohol abuse, impaired functional status, and hypoalbuminemia. Precipitating factors include residual anesthetic and drug effects (especially after premedication with anticholinergic drugs), postoperative hypoxia, perioperative hypotension, electrolyte imbalances, infections, psychological stress, and multiple awakenings with fragmented sleep. There is no clear correlation of delirium with specific anesthetic route. Postoperative delirium may start at any time but often becomes evident about the third day and abates by the seventh, although it may last considerably longer.

A number of surgeries are associated with a high rate of postoperative delirium. Between 30% and 40% of patients experience delirium after open heart or coronary artery bypass surgery. Patients older than 60 years are at special risk for postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Additional factors are decreased postoperative cardiac output and length of time on cardiopulmonary bypass machine, with its added risk for microemboli. In addition to an already high rate of delirium following fractures (up to 35.6% after hip fracture), orthopedic surgeries, particularly femoral neck fractures and bilateral knee replacements, further increase the frequency of delirium by about 18%. Emergency hip fracture repair is associated with a higher risk of delirium than elective hip surgery (Bruce et al., 2007). Elective noncardiac thoracic surgery is also associated with a 9% to 14% frequency of delirium in the elderly. Cataract surgery is associated with a 7% frequency of delirium, possibly because of sensory deprivation. Patients who have undergone prostate surgery may develop delirium associated with water intoxication as a result of absorption of irrigation water from the bladder.

Other Neurological Causes

Other CNS disturbances predispose to delirium. In general, patients with dementia, Lewy body disease, Parkinson disease, and atrophy or subcortical ischemic changes on neuroimaging are particularly susceptible. Electroconvulsive therapy often produces a delirium of one week or more. Head trauma can result in delirium as a consequence of brain concussion, brain contusion, intracranial hematoma, or subarachnoid hemorrhage (see Chapters 51B and 51C). Moreover, subdural hematomas can occur in the elderly with little or no history of head injury. Rapidly growing tumors in the supratentorial region are especially likely to cause delirium with increased ICP. Paraneoplastic processes produce limbic encephalitis and multifocal leukoencephalitis. Delirium can result from acute demyelinating diseases and other diffuse multifocal lesions, and from communicating or noncommunicating hydrocephalus. Some patients with transient global amnesia have initial delirium before the pathognomonic and prominent anterograde amnesia. Transient global amnesia patients also have limited retrograde amnesia for the preceding hours and improve within 24 hours. In Wernicke encephalopathy, delirium accompanies oculomotor paresis, nystagmus, ataxia, and frequently residual amnesia (Korsakoff psychosis).

Miscellaneous Causes

Various other disturbances can produce delirium. Bone fractures are associated with delirium in the elderly, and about 50% of those admitted with a hip fracture have delirium. Time from admission to operation in these patients is an additional risk factor for development of preoperative delirium (Juliebo et al., 2009). In orthopedic cases, the possibility of fat emboli requires evaluation of urine, sputum, or cerebrospinal fluid for fat. ICU psychosis is associated with sleep deprivation, immobilization, unfamiliarity, fear, frightening sensory overstimulation or sensory deprivation, isolation, transfer from another hospital ward, mechanical ventilation, psychoactive medications, and use of drains, tubes, and catheters (Van Rompaey et al., 2009). Delirium results from blood dyscrasias including anemia, thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Finally, physical factors such as heatstroke, electrocution, and hypothermia may be causal.

Special Problems in Differential Diagnosis

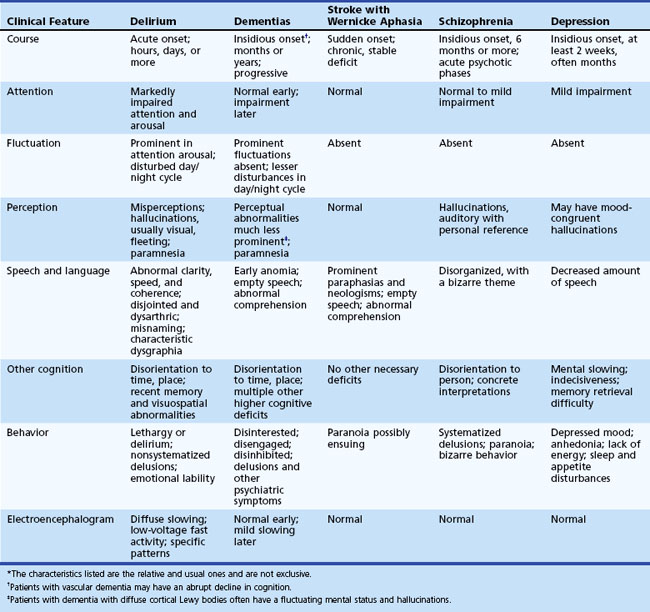

Delirium must be distinguished from dementia, Wernicke aphasia, and psychiatric conditions (see Chapters 6, 8, 9, and 12A). The main differentiating features of dementia are the longer time course and the absence of prominent fluctuating attentional and perceptual deficits. Chronic confusional states lasting 6 months or more are a form of dementia. Patients with delirium that becomes chronic tend to settle into a lethargic state without the prominent fluctuations throughout the day, and they have fewer perceptual problems and less disruption of the day/night cycle. In addition, delirium and dementia often overlap because demented patients have increased susceptibility for developing a superimposed delirium. Demented patients who suddenly get worse should always be evaluated for delirium. Moreover, distinguishing delirium from certain forms of dementia such as vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies may be particularly difficult. Patients with vascular dementia may have an acute onset or sharp decline in cognition similar to delirium. Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies have fluctuations in attention and alertness and visual hallucinations that can look identical to delirium. Most of these patients, however, have parkinsonism, repeated falls, or other supportive features. Nevertheless, the differential diagnosis of delirium and dementia with Lewy bodies may not be possible until after a diagnostic workup is completed.

Psychiatric conditions that may be mistaken for delirium include schizophrenia, depression, mania, attention deficit disorder, autism, dissociative states, and Ganser syndrome, which is characterized by ludicrous or approximate responses (see Chapter 8). In general, patients with psychiatric conditions lack the fluctuating attentional and related deficits associated with delirium. Schizophrenic patients may have a very disturbed verbal output, but their speech often has an underlying bizarre theme. Schizophrenic hallucinations are more often consistent persecutory voices rather than fleeting visual images, and their delusions are more systematized and have personal reference. Conversely, delirious hallucinations are usually visual, and the delusions are more transitory and fragmented. Mood disorders may also be mistaken for delirium, particularly if there is an acute agitated depression or a predominantly irritable mania. A general rule is that psychiatric behaviors such as psychosis or mania may be due to delirium, especially if they occur in someone who is 40 years or older without a prior psychiatric history. They should be regarded as delirium until proven otherwise.

Table 4.2 outlines the special problems that must be considered in the differential diagnosis of delirium.

Prevention and Management

As many as 30% to 40% of cases of delirium may be prevented with provision of high-quality care (Inouye, 2006). Misdiagnosis of delirium results in inadequate management in up to 80% of patients (Michaud et al., 2007), and about half of elderly patients affected by delirium actually develop symptoms after admission to the hospital. Early identification of patients with predisposing risk factors is important, especially in a frail geriatric population (Laurila et al., 2008). In addition, early intervention by geriatricians and admission to geriatric-focused inpatient hospital wards have been shown to reduce delirium rates (Bo et al., 2009; Marcantonio et al., 2001). Multifactorial intervention programs can reduce the duration of delirium, length of hospital stay, and mortality (Bergmann et al., 2005; Inouye et al., 1999; Lundstrom et al., 2005). These programs focus on managing risk factors such as cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual and hearing impairment, and dehydration, particularly in intermediate-risk patients (Inouye et al., 1999). They also focus on educational programs for physicians and nurses in the detection and management of delirium. Nurses in particular spend more time with patients than physicians do, and they may be in a better position to recognize delirium.

In general, it is best to avoid the use of drugs in confused patients, because they further cloud the picture and may worsen delirium. All the patient’s medications should be reviewed, and any unnecessary drugs should be discontinued. When medication is needed, the goal is to make the patient manageable, not to decrease loud or annoying behavior or to sedate them (Inouye, 2006). These patients should receive the lowest possible dose and should not get drugs such as phenobarbital or long-acting benzodiazepines. In particular, use of benzodiazepines can have a paradoxical effect in the elderly, causing agitation and confusion. Medication may be necessary if the patient’s behavior is potentially dangerous, interferes with medical care, or causes the patient profound distress. Clinicians most often use haloperidol (starting at 0.25 mg daily) for these symptoms. Haloperidol may be repeated every 30 minutes, PO or IM, up to a maximum of 5 mg/day. After the first 24 hours, 50% of the loading dose may be given in divided doses over the next 24 hours, then the dose should be tapered off over the next few days (Inouye, 2004). The atypical antipsychotics—risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole—may be used at low doses (Attard, Ranjith, and Taylor, 2008). Safety and efficacy of the atypical and typical antipsychotics are similar (Fong, Tulebaev, and Inouye, 2009). Results in favor of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for delirium management have not been borne out in controlled trials, though in some cases, such as in patients with Lewy body dementia, they can be helpful (Attard, Ranjith, and Taylor, 2008; Tabet and Howard, 2009). Other medications such as valproate, ondansetron, or melatonin may be effective and safe in selected cases. Finally, there is no evidence for the preventive use of haloperidol or related medications prior to the development of delirium, though it may reduce severity and duration postoperatively, as well as duration of hospital stay (Kalisvaart et al., 2005). Evidence for preventive use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors after surgery is also not supportive, though this conclusion is based only on small pilot studies (Attard, Ranjith, and Taylor, 2008; Tabet and Howard, 2009).

Prognosis

The prognosis for recovery from delirium is variable. If the causative factor is rapidly corrected, recovery can be complete, with an average duration of delirium of about 8 days (2 days to 2 weeks). Delirium present at discharge is associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of death or nursing home placement (McAvay et al., 2006), and delirium persisting after hospital discharge is associated with a 2.9-fold risk of death within the following year. This risk appears to be reversible with the resolution of delirium (Kiely et al., 2009). The link between delirium and subsequent long-term cognitive impairment is also firmly established (MacLullich et al., 2009).

In the elderly, delirium may not be a transient disorder. For them, the duration of delirium is often longer than that of their underlying medical problem. Moreover, after hospital discharge, older patients who are delirious may not recover back to baseline (Fong, Tulebaev, and Inouye, 2009; MacLullich et al., 2009; McCusker et al., 2002). In one study, 14.8% still met criteria for delirium 12 months after discharge (Rockwood et al., 1999). A partial delirium with some but not all criteria for delirium may persist in many elderly patients.

Delirium is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in older hospitalized patients; particularly in the presence of baseline cognitive impairment or dementia, it is associated with an increased mortality rate and may accelerate cognitive decline (Adamis et al., 2006; MacLullich et al., 2009; McCusker et al., 2002). Delirium in the elderly predicts sustained poor cognitive and functional status and increased likelihood of nursing home placement after a medical admission. Hypoactive delirious patients appear to be at particular risk because of complications from aspiration and inadequate oral nutrition as well as falls and pressure sores. In general, however, clinicians can greatly improve prognosis with increased awareness of delirium, more rapid diagnosis of the causative factor(s), and better overall management.

Adamis D., Sharma N., Whelan P.J., et al. Delirium scales: a review of current evidence, J. Aging Ment Health. 2010:1-13.

Adamis D., Treloar A., Martin F.C., et al. Recovery and outcome of delirium in elderly medical inpatients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;43(2):289-298.

Anderson D. Preventing delirium in older people. Br Med Bull. 2005;73-74:25-34.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Edition). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Attard A., Ranjith G., Taylor D. Delirium and its treatment. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(8):631-644.

Bergmann M.A., Murphy K.M., Kiely D.K., et al. A model for management of delirious postacute care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1817-1825.

Bo M., Martini B., Ruatta C., et al. Geriatric ward hospitalization reduced incidence delirium among older medical inpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(9):760-768.

Breitbart W., Gibson C., Tremblay A. The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):183-194.

Breitbart W., Rosenfeld B., Roth A., et al. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128-137.

Bruce A.J., Ritchie C.W., Blizard R., et al. The incidence of delirium associated with orthopedic surgery: a meta-analytic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(2):197-214.

Caplan L.R. Cardiac encephalopathy and congestive heart failure: a hypothesis about the relationship. Neurology. 2006;66(1):99-101.

Cole M.G. Delirium in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):7-21.

Elie M., Cole M.G., Primeau F.J., Bellavance F. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):204-212.

Ely E.W., Inouye S.K., Bernard G.R., et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703-2710.

Engel G.L., Romano J. Delirium, a syndrome of cerebral insufficiency. J Chronic Dis. 1959;9(3):260-277.

Fong T.G., Tulebaev S.R., Inouye S.K. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

Inouye S.K. A practical program for preventing delirium in hospitalized elderly patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(11):890-896.

Inouye S.K. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

Inouye S.K., Bogardus S.T.Jr., Charpentier P.A., et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

Inouye S.K., Charpentier P.A. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275(11):852-857.

Inouye S.K., Foreman M.D., Mion L.C., et al. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467-2473.

Johnson M.H. Assessing confused patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(Suppl 1):i7-12.

Juliebo V., Bjoro K., Krogseth M., et al. Risk factors for preoperative and postoperative delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1354-1361.

Kalisvaart K.J., de Jonghe J.F., Bogaards M.J., et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1658-1666.

Kiely D.K., Marcantonio E.R., Inouye S.K., et al. Persistent delirium predicts greater mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):55-61.

Laurila J.V., Laakkonen M.L., Tilvis R.S., et al. Predisposing and precipitating factor for delirium in a frail geriatric population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):249-254.

Lundstrom M., Edlund A., Karlsson S., et al. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):622-628.

MacLullich A.M., Beaglehole A., Hall R.J., et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive impairment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(1):30-42.

Maclullich A.M., Ferguson K.J., Miller T., et al. Unravelling the pathophysiology of delirium: a focus on the role of aberrant stress responses. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):229-238.

Marcantonio E.R., Flacker J.M., Wright R.J., et al. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522.

McAvay G.J., Van Ness P.H., Bogardus S.T., et al. Older adults discharged from the hospital with delirium: 1-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(8):1245-1250.

McCusker J., Cole M., Abrahamowicz M., et al. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):457-463.

McCusker J., Cole M.G., Dendukuri N., et al. The delirium index, a measure of the severity of delirium: new findings on reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1744-1749.

Michaud L., Bula C., Berney A., et al. Delirium: guidelines for general hospitals. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):371-383.

Neelon V.J., Champagne M.T., Carlson J.R., et al. The NEECHAM Confusion Scale: construction, validation, and clinical testing. Nurs Res. 1996;45(6):324-330.

Reischies F.M., Neuhaus A.H., Hansen M.L., et al. Electrophysiological and neuropsychological analysis of a delirious state: the role of the anterior cingulate gyrus. Psychiatry Res. 2005;138(2):171-181.

Robinson T.N., Raeburn C.D., Tran Z.V., et al. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):173-178.

Rockwood K., Cosway S., Carver D., et al. The risk of dementia and death after delirium. Age Ageing. 1999;28(6):551-556.

Rudolph J.L., Jones R.N., Grande L.J., et al. Impaired executive function is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):937-941.

Tabet N., Howard R. Pharmacological treatment for the prevention of delirium: review of current evidence. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(10):1037-1044.

Trzepacz P.T., Mittal D., Torres R., et al. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229-242.

Trzepacz P.T., van der Mast R. The neurophysiology of delirium, In. Lindesay J., Rockwood K., Macdonald A.. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications. 2002:51-90.

van Munster B.C., de Rooij S.E., Korevaar J.C. The role of genetics in delirium in the elderly patient. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(3):187-195.

van Munster B.C., Yazdanpanah M., Tanck M.W., et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the DRD2, DRD3, and SLC6A3 gene in elderly patients with delirium. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(1):38-45.

Van Rompaey B., Elseviers M.M., Schuurmans M.J., et al. Risk factors for delirium in intensive care patients: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2009;13(3):R77.

Winawer N. Postoperative delirium. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1229-1239.