CHAPTER 11 DELIRIUM

Delirium may be caused by specific brain injury (e.g., herpes simplex encephalitis), but more often, delirium is a nonspecific response of the brain to challenges from systemic illness or medications. Delirium can occur in otherwise normal brains with extreme physiological challenge (e.g., intensive care admission), but in diseased brains (e.g., Alzheimer’s dementia), even apparently trivial challenges, such as a urinary tract infection or constipation, may trigger delirium. Delirium may be caused by just one factor (e.g., recreational drug use) but commonly appears to result from a combination of harmful factors.

DEFINITION

Many terms have been used to describe the delirious state, including acute organic brain syndrome, acute confusional state, toxic psychosis, intensive care unit (ICU) syndrome, and postoperative psychosis. This variation reflects the difficulty in describing the syndrome or syndromes that are now most commonly called delirium. The most common definition used in delirium research is that of the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (Fig. 11-1).1

Figure 11-1 Rights were not granted to include this figure in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for delirium. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

The key features of delirium are acute change in cognitive status, fluctuation in consciousness, deficits in attention, and perceptual disturbances.1 Nonarbitrary definitions of these features, especially consciousness and attention, are lacking, and this limits the ability to define delirium precisely.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prevalence and Incidence

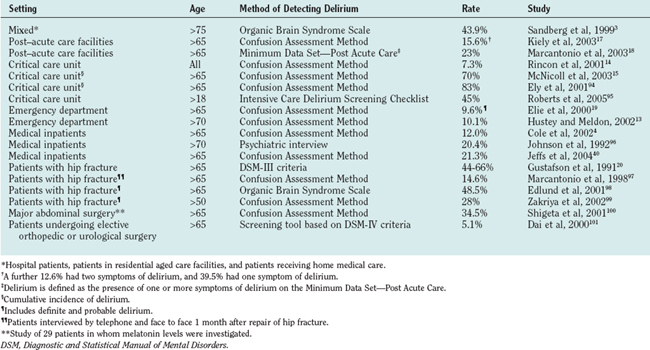

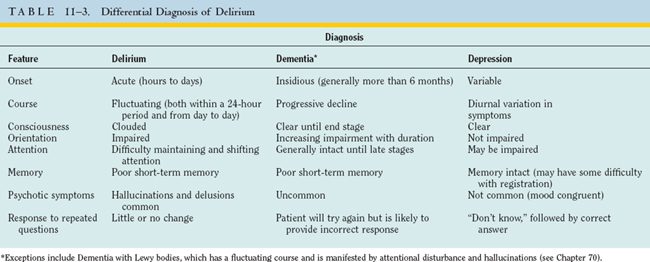

Delirium is common (Table 11-1). The prevalence of delirium in hospitalized older patients is 14% to 60%; the rates are higher in surgical patients (particularly those with hip fracture or requiring emergency surgery).2–6 Approximately 1 per 10 elderly patients presenting to hospital are delirious, and a further 10% to 40% develop delirium while hospitalized.7 Delirium occurs in up to 45% of hospitalized patients with preexisting cognitive impairment.8 Delirium is even more common in patients nearing the end of life, occurring in up to four fifths of such patients.9,10 Delirium occurs in 10% of patients presenting to emergency departments and is almost universal in intensive care units.11–16 Of patients admitted to post–acute care facilities, 16% have a diagnosis of delirium, and a further 23% to 53% have symptoms of delirium at the time of admission.17,18

Despite the high incidence and prevalence of delirium, it remains underrecognized by clinicians—up to 90% of cases in inpatients are missed.13,19–26 Furthermore, patients are discharged home from the emergency department without delirium being recognized, and this has been linked to increased mortality.12,13,23

Clinical Syndromes

Delirium is not a homogenous disorder; rather, it is a complex clinical syndrome with diverse etiologies and presentations. Delirium tremens is the classic picture of delirium with which most clinicians are familiar. Agitation; being out of touch with reality, with visual, tactile, and auditory hallucinations; obvious fear; and suspicion and mistrust of others typify the hyperactive form of delirium. The hypoactive form of delirium is recognized from apathy in patients with marked cognitive impairment. Hypoactive delirium is easily missed, inasmuch as there are no behavioral disturbances that bring attention to the patients and the patients seldom volunteer that they are experiencing psychotic thoughts or bizarre sensations.

About 25% of cases of delirium are of the hyperactive form, another 25% are of the hypoactive form, and the remainder of patients with delirium have both hyperactive and hypoactive features.3,27,28 The cause of delirium cannot be reliably diagnosed from the subtype observed, although drug withdrawal states more commonly manifest with the hyperactive form and metabolic encephalopathies with the hypoactive form.28,29 Infection may manifest with either form of delirium.30,31

Patients who have some of the key features of delirium but do not fully satisfy the DSM-IV criteria experience adverse events similar to those who do meet the criteria. This “subsyndromal delirium” has been associated with poor outcomes, and there is probably a relationship between the number of features present and the risk of adverse outcomes.32,33

Course

Delirium often lasts for a few days or a week, but some patients experience prolonged delirium. One study showed that only approximately one fifth of patients have complete resolution of delirium at 6 months.34 Symptoms of memory impairment, inattention, and disorientation may still be present 12 months after an episode of delirium.35 Prolonged delirium leads to diagnostic difficulty, especially when the precipitating event has apparently resolved, and it may be difficult to distinguish delirium from dementia. Dementia with Lewy bodies, with its characteristic attentional fluctuations causes particular difficulty (see Chapter 71). Nearly one in five patients has a new diagnosis of dementia in the year after an episode of delirium.36 The existence of prolonged delirium also makes it difficult to predict recovery of individual patients and complicates decisions about rehabilitation potential and long-term care.

Sequelae

Physical

Delirium is associated with major morbidity and mortality. Patients suffering from delirium have an initial mortality rate of up to 26%.37 Twelve months after an episode of delirium, patients are twice as likely to have died than are similar patients who have not had delirium.36,38 Mortality rates as high as 75% three years after an episode of delirium have been reported.39

Complications attributable to delirium include malnutrition, dehydration, pneumonia, pressure sores, and falls. Patients with delirium suffer greater functional decline in hospital, and are more likely to require rehabilitation or long-term residential care.34,40–43 Patients with hyperactive delirium are more likely to fall while hospitalized.30 Patients with hypoactive delirium are generally sicker, remain hospitalized longer, and are more likely to develop pressure sores.30

Social and Economic

Delirium often imposes a heavy burden on the families of those affected as they come to terms with a serious condition that substantially alters the behavior of their family member and that has an uncertain prognosis. It also creates an economic burden for health care systems as a result of increased duration of hospitalization and increased postdischarge costs.44–46

RISK FACTORS

Baseline Vulnerability

Factors that increase vulnerability to delirium include preexisting cognitive impairment, comorbid illness, and sensory deficits (Table 11-2).11,45,47,48

TABLE 11-2 Baseline Vulnerability and Precipitating Factors for Delirium

| Risk Factor* | Adjusted Relative Risk |

|---|---|

| Cognitive impairment/dementia11,45,47,48 | 2.1-5.3 |

| Number of major diagnostic categories45 | 1.7 |

| Depression11,45 | 1.9-3.2 |

| Alcoholism11,45 | 3.3-5.7 |

| Severe medical illness11,58 | 3.5-5.9 |

| Male gender11 | 1.9 |

| Abnormal sodium11,47 | 2.2-6.2 |

| Hearing impairment11 | 1.9 |

| Visual impairment11,48 | 1.7-3.5 |

| Diminished ADL11 | 2.5 |

| Fever or hypothermia47 | 5.0 |

| Psychoactive drug use47 | 3.9 |

| Azotemia/dehydration47 | 2.0-2.9 |

| Use of physical restraints52 | 4.4 |

| Malnutrition52 | 4.0 |

| More than three medications added in 24 hours52 | 2.9 |

| Use of indwelling urinary catheter52 | 2.4 |

| Any iatrogenic event52 | 1.9 |

ADL, activities of daily living.

* References cited as superscripts.

A delirium risk prediction model based on the presence or absence of cognitive impairment, severe illness, visual impairment, and dehydration at the time of admission to hospital shows that when one or two risk factors are present, the rate of incident delirium is 16% to 23%, whereas when three or four risk factors are present, the rate of delirium is 32% to 83%.48 The magnitude of the noxious event or events necessary to produce a delirious episode is inversely proportional to the degree of baseline vulnerability. In vulnerable people, delirium acts as a sensitive, but not specific, indicator of illness.

Precipitating Factors

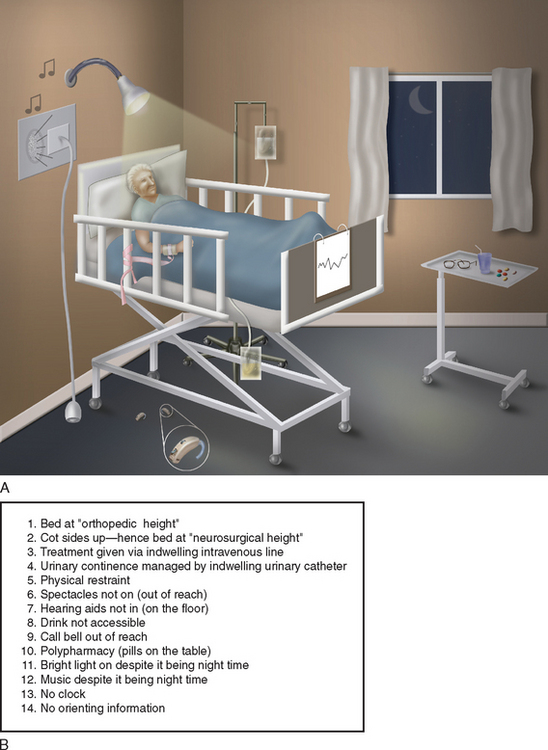

The study of precipitating factors is plagued by confounding variables. The confounding variables (in this case, putative risk factors for delirium, such as prescription of new medications or insertion of a urinary catheter) are related to both the study factor (sickness that necessitates hospitalization and in turn may necessitate the new medications or catheterization) and the outcome factor (delirium that may be caused by the sickness, the interventions, or both). Confounding cannot be adjusted for statistically. Because it would be unethical to subject healthy people to medications, procedures, or hospitalization to test these as independent risk factors for delirium, the evidence regarding precipitating factors comes from descriptive studies. Nonetheless, the weight of evidence shows that many events may precipitate delirium. Delirium is a syndrome with multifactorial etiologies; therefore, in any one patient, it is usual for a number of factors to contribute to delirium.49–51 Five independent risk factors associated with the hospitalization process that appear to increase the risk of developing delirium are (1) the addition of more than three medications in any 24-hour period, (2) the use of physical restraints, (3) the presence of malnutrition, (4) the insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter, and (5) any iatrogenic adverse event.52 The risk of delirium rises proportionately with the number of risk factors. Of importance is that these precipitating factors are potentially avoidable. Patients with three or more precipitating factors have an 8% per day risk of developing delirium.52 Other environmental factors, such as frequent room changes, absence of a clock, or absence of reading glasses, are associated with increased “severity” of delirium.53 Figure 11-2A depicts a hospital environment likely to produce delirium, whereas Figure 11-2C depicts a hospital environment likely to decrease the risk of delirium.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

It is not surprising, in view of the myriad of etiologies and manifestations of delirium, that there is no one satisfactory unifying pathophysiological explanation. In addition, the neural mechanisms by which delirium is produced are poorly understood. To date, proposed pathophysiological mechanisms remain excessively simplistic or, when detailed, cannot explain adequately the various manifestations of delirium. It is not clear whether delirium is the final common pathway for a broad range of insults or whether the different causes of delirium have different pathophysiological processes that are clinically indistinguishable. Delirium is believed to occur as a result of perturbation to systems that have little reserve, and this fits well with the clinical risk prediction tools.

A number of neurotransmitter systems have been implicated in the pathophysiology of delirium. Abnormalities of the cholinergic system are the best studied. The notion that a central cholinergic deficiency leads to delirium is supported clinically by the observation that anticholinergic medications are potent causes of delirium.54,55 Investigators measuring serum anticholinergic activity have reported increased levels associated with the presence of delirium, with levels falling after resolution of delirium.56 Physostigmine, a reversible anticholinesterase inhibitor, has been used to treat anticholinergic delirium with some success.57 Cholinesterase inhibitors have been proposed as a means of treating delirium, with some case reports of success, but, conversely, tacrine has been reported to cause delirium.58,59 Excess dopamine has been implicated in the pathogenesis of delirium, and dopamine antagonists are used to treat delirium.60,61 Both serotonin excess and deficiency have been implicated; serotonin excess appears more likely to be associated with medication-related delirium.55 There is no conclusive evidence to relate either dopamine or γ-amino butyric acid to medical or surgical delirium, but perturbation of its activity has been linked with hepatic encephalopathy and benzodiazepine intoxication or withdrawal states.62,63 Hypercortisolism, such as that occurring in Cushing’s syndrome, is known to have effects on cognition, as well as on mood and sleep, but no decisive link with delirium has been established.55 Animal models such as stressed rats show changes in steroid sensitive hypothalamic neurones that can be prevented by adrenalectomy.64

CLINICAL FEATURES

Cognitive Examination

Fluctuating impairment of sustained directed attention is a key feature of delirium and may become apparent when patients have difficulty attending to questions in the medical interview or are easily distracted during conversation. Attention may be formally assessed by such items such as the Digit Span Memory Test or Trail Making Test.65 Restlessness or picking at the bedclothes may indicate underlying psychotic features. Patients should be questioned with regard to worrying thoughts or unusual sensory experiences in order to elicit the presence of hallucinations or delusions.

Incorporating a screening test for cognition, such as the Mini Mental State Examination, in the initial assessment of hospitalized older patients could substantially improve the detection of delirium.66,67 Poor test performance would prompt clinicians to seek other evidence of delirium.

Neurological Examination

Patients with small infarcts that result in Wernicke’s aphasia without other focal signs sometimes receive misdiagnoses of delirium. The lack of disturbance of sustained directed attention helps rule out delirium, and the characteristic language disturbance helps make a positive diagnosis of Wernicke’s syndrome (see Chapter 3).

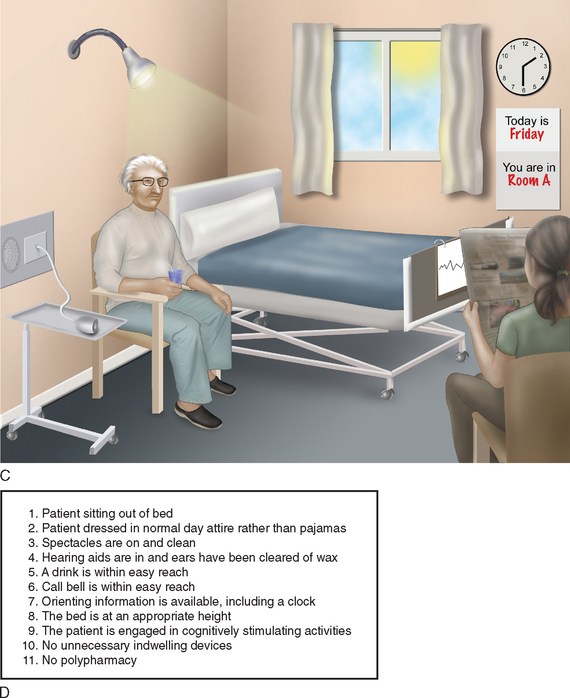

Differentiation of delirium from depression can be particularly challenging; depressive features such as apathy and complaints of depressed mood are common in delirium. Up to one half of the patients referred for psychiatric consultation for depressive symptoms in hospital actually have delirium.68–70 The differentiation of the disorders is especially important because many antidepressants have anticholinergic properties that have a marked potential to aggravate delirium. Conversely, when depression is misdiagnosed as chronic delirium, the opportunity for antidepressant therapy is lost. Table 11-3 outlines useful features for the differentiation of delirium from other common conditions.

Diagnostic Instruments

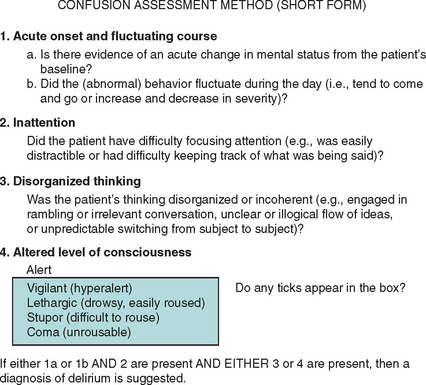

There is no single diagnostic test for the presence of delirium; the reference standard instrument is a formal psychiatric assessment. The Confusion Assessment Method (Fig. 11-3) is relatively short, and nonmedical staff can be trained to administer it.71 However, this test is not valid when administered by nurses involved in the routine care of patients unless they also perform the Mini Mental State Examination.72

MANAGEMENT

Aims of Management

The best available evidence suggests that prevention of delirium is more effective than its treatment.37,73,74 Useful principles for the treatment of established delirium focus on investigation of possible causes, prevention of complications, and the management of behavioral disturbance.

Prevention

Addressing the known risk factors for delirium can prevent the occurrence of delirium while the patient is hospitalized.75 One multidisciplinary intervention reduced the rate of incident delirium by one third in medical patients at intermediate to high risk.75 This program aimed to ameliorate the delirium risk factors of cognitive impairment, dehydration, immobility, sensory impairment, and sleep disturbance.76 Education programs or clinical guidelines for hospital staff that were aimed at the prevention of delirium have yielded mixed results.77,78 Perioperative interventions that have reduced delirium incidence include the provision of continuous supplementary low-flow oxygen, the use of analgesic protocols, and a geriatric consultation service to elderly patients with hip fracture.33,79,80

Investigating the Cause of Delirium

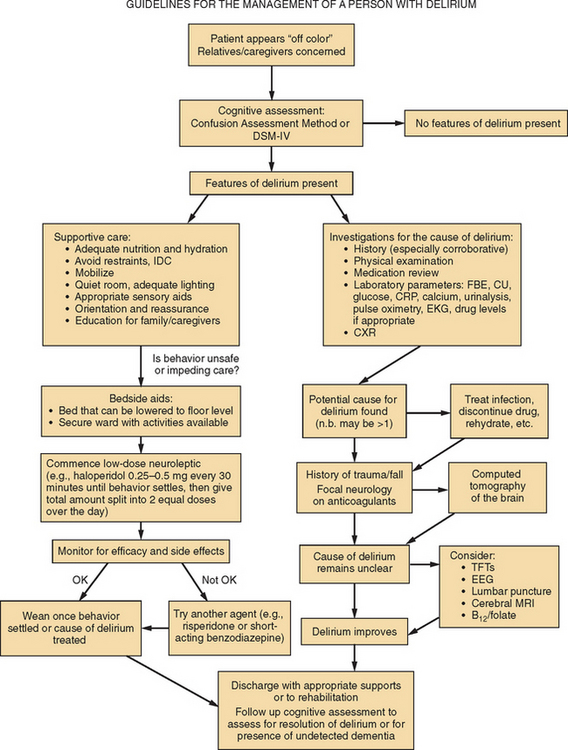

Investigation is directed toward the likely cause. In children, the emphasis is on the search for infection. In young adults, investigations focus on drug intoxication/withdrawal and central nervous system infections, including the human immunodeficiency virus, and rare encephalopathies (arteritis, disseminated neoplasm). In older people, the causes of delirium are the causes of acute illness in older people; medication side effects, metabolic derangement, and occult infections are the most common. Investigations are directed at these and at ruling out less common etiological factors (Table 11-4). Medications are responsible for 22% to 39% of cases, and thus a medication review, including over-the-counter drugs, often identifies a potential cause (Table 11-5).6 In addition to obvious candidates (e.g., sedatives or hypnotics, anticonvulsants, and antidepressants), many common medications (e.g., frusemide, digoxin, and prednisolone) have significant anticholinergic activity and may contribute to the development of delirium.56 In up to 62% of cases, more than one etiological factor is involved.49–51 Figure 11-4 provides a suggested algorithm for the investigation of the cause of delirium.

TABLE 11-5 Drugs Commonly Implicated in Delirium

No clear cause can be found in some cases.6 The search for potential causes for delirium is complicated by the frequently atypical disease manifestations in elderly patients, in addition to the obvious practical difficulties of documenting histories from confused patients.

The investigation of delirium must be considered in view of the patients’ own constellation of illnesses, and any algorithm can act only as a guide. Neuroimaging such as computed tomography of the brain commonly reveals underlying pathology but is often unhelpful in elucidating the etiology of delirium. Only rarely is delirium the result of a primary neurological event.6,81 Focal neurological signs or a history of head trauma would prompt urgent cerebral computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The electroencephalogram characteristically shows generalized background slowing and only rarely helps establish the cause of delirium. However, the excessive frontal beta activity of benzodiazepine or barbiturate intoxication can be a helpful diagnostic pointer. The electroencephalogram can rule out nonconvulsive status epilepticus, which can at times be indistinguishable from hypoactive delirium, and it may also assist in the differentiation of delirium from functional psychoses (the end stage of Wernicke’s encephalopathy).82

Treatment

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is more common than usually realized, and 1% to 5% of postmortem specimens show evidence of Korsakoff’s pathology in two Australian coronial series.83 Most patients present with only a delirium, rather than with the classic triad of memory loss, ocular signs, and confabulation. For this reason, all patients presenting with delirium for which another cause is not immediately apparent should receive thiamine.

Nonpharmacological Measures

With the exception of physical restraints, which worsen delirium and cause serious injuries and deaths, the use of nonpharmacological measures in the treatment of established delirium is not associated with harm and hence should be used exhaustively as the mainstay of management.52,53,72,84–89 Nonpharmacological management focuses on providing prompts to assist orientation, an environment conducive to appropriate rest, and activities to maintain cognitive stimulation and physical activity. Providing verbal and visual reminders of the date, time, place, and the daily schedule helps. When appropriate, clean spectacles and functioning hearing aids help this orienting process. Nursing provided by a small number of nurses (primary nursing) is less disorienting than team nursing. For agitated patients, a person who sits with the patient can improve safety. Equipment that immobilizes patients, such as indwelling urinary and intravenous catheters, should be avoided. Patients should ambulate at least three times daily; participation in self-care tasks helps achieve this.

Sensitive involvement of patients in normal daily activities helps them maintain mobility and adequate nutrition and minimizes constipation and urine retention. It is preferable to care for delirious patients in single rooms, where noise and distractions can be kept to a minimum, and a few objects brought from home can provide a sense of familiarity.38 Some institutions have designed rooms specifically to manage delirious patients, but these have yet to be prospectively evaluated.90

Pharmacological Measures

There is a paucity of research into the pharmacological management of delirium, and there is no evidence to suggest that the use of antipsychotic or other medications alters the natural history of delirium or improves outcome.91 Mainly, there is no evidence of benefit, but there is also evidence of little or no benefit. Antipsychotic drugs are often employed, but they can have unwanted side effects. The aim of treatment must be to relieve suffering or to ensure the safety of patients. Chemical restraint should be avoided, because oversedation leads to falls, pneumonia, and pressure sores. Agitation in delirium may be caused by fear from misperceptions, hallucinations, or delusions. Antipsychotic agents may relieve some of the symptoms. Some patients without obvious agitation experience marked delusional thoughts that might lead them to refuse food, fluids, or medications.

The aim of pharmacotherapy for patients with nonspecific delirium is to treat the symptoms. The aim is not to sedate patients, not to make them less mobile, or not to make them less disruptive to nursing staff or family members, but to decrease inner turmoil. Most evidence regarding pharmacotherapy in delirium comes from case reports or small, uncontrolled series.91 Haloperidol at a low dosage (e.g., starting at 0.5 to 1 mg) can be effective in controlling psychotic symptoms and is probably superior to benzodiazepines.60 Care must be taken to avoid oversedation, and patients must be monitored for adverse effects such as postural hypotension, extrapyramidal side effects, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. If a psychoactive agent fails, it seems prudent to discontinue it rather than continuing it and adding to it. If it is still believed to be required, another agent could be commenced in place of the first.

Delirium tremens is a different situation and is best treated with benzodiazepines.92 See Chapter 117 for a withdrawal management protocol.

Figure 11-4 provides a guide to the management of patients with delirium.

Ethical Issues and Decision-Making Capacity

Many patients with delirium lose the capacity to make health-related or other decisions during the delirium. Some may never regain this capacity, whereas for others, this incapacity is temporary and may fluctuate from hour to hour and day to day. Therefore, this capacity must be assessed whenever decisions are to be made. Adequate assessments are seldom performed, and the use of surrogate decision makers is suboptimal.27 A formal capacity assessment process may help provide valid assessments.93

CONCLUSION

Darzins P, Molloy D, Strang D. Who can decide? The six step capacity assessment process. Adelaide, Australia: Memory Australia Press, 2000;144.

Inouye SK. Delirium: A Barometer for Quality of Hospital Care. Hosp Pract (Minneap). 2001;36(2):15-16. 18.

Lindesay J, Rockwood K, Macdonald A. Delirium in Old Age. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002;238.

Rockwood K, Bhat R. Should We Think Before We Treat Delirium? Intern Med J. 2004;34:76-78.

Weber JB, Coverdale JH, Kunik ME. Delirium: Current Trends in Prevention and Treatment. Intern Med J. 2004;34:115-121.

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

2 Rockwood K. Acute confusion in elderly medical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:150-154.

3 Sandberg O, Gustafson Y, Brannstrom B, et al. Clinical profile of delirium in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1300-1306.

4 Cole MG, McCusker J, Dendukuri N, et al. Symptoms of delirium among elderly medical inpatients with or without dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14:167-175.

5 Fick D, Foreman M. Consequences of not recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia in hospitalized elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26:30-40.

6 Inouye SK. The dilemma of delirium: clinical and research controversies regarding diagnosis and evaluation of delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients. Am J Med. 1994;97:278-288.

7 Roche V. Southwestern Internal Medicine Conference. Etiology and management of delirium. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:20-30.

8 Rockwood K. The occurrence and duration of symptoms in elderly patients with delirium. J Gerontol. 1993;48:M162-M166.

9 Caraceni A, Nanni O, Maltoni M, et al. Impact of delirium on the short term prognosis of advanced cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. Cancer. 2000;89:1145-1149.

10 Casarett DJ, Inouye SK. Diagnosis and management of delirium near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:32-40.

11 Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:204-212.

12 Naughton BJ, Moran MB, Kadah H, et al. Delirium and other cognitive impairment in older adults in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:751-755.

13 Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:248-253.

14 Rincon HG, Granados M, Unutzer J, et al. Prevalence, detection and treatment of anxiety, depression, and delirium in the adult critical care unit. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:391-396.

15 McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, et al. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:591-598.

16 Bergeron N, Skrobik Y, Dubois MJ. Delirium in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2002;6:181-182.

17 Kiely DK, Bergmann MA, Murphy KM, et al. Delirium among newly admitted postacute facility patients: prevalence, symptoms, and severity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M441-M445.

18 Marcantonio ER, Simon SE, Bergmann MA, et al. Delirium symptoms in postacute care: prevalent, persistent, and associated with poor functional recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:4-9.

19 Elie M, Rousseau F, Cole M, et al. Prevalence and detection of delirium in elderly emergency department patients. CMAJ. 2000;163:977-981.

20 Gustafson Y, Brannstrom B, Norberg A, et al. Underdiagnosis and poor documentation of acute confusional states in elderly hip fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:760-765.

21 Inouye SK. The recognition of delirium. Hosp Pract (Off Ed). 1991;26(4A):61-62.

22 Johnson J. Identifying and recognizing delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:353-358.

23 Kakuma R, du Fort GG, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:443-450.

24 Cameron DJ, Thomas RI, Mulvihill M, et al. Delirium: a test of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual III criteria on medical inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:1007-1010.

25 Milisen K, Foreman MD, Wouters B, et al. Documentation of delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28:23-29.

26 Rockwood K, Cosway S, Stolee P, et al. Increasing the recognition of delirium in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:252-256.

27 Auerswald KB, Charpentier PA, Inouye SK. The informed consent process in older patients who developed delirium: a clinical epidemiologic study. Am J Med. 1997;103:410-418.

28 Meagher DJ, O’Hanlon D, O’Mahony E, et al. Relationship between symptoms and motoric subtype of delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:51-56.

29 Camus V, Gonthier R, Dubos G, et al. Etiologic and outcome profiles in hypoactive and hyperactive subtypes of delirium. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2000;13:38-42.

30 O’Keeffe ST, Lavan JN. Clinical significance of delirium subtypes in older people. Age Ageing. 1999;28:115-119.

31 Ross CA, Peyser CE, Shapiro I, et al. Delirium: phenomenologic and etiologic subtypes. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3:135-147.

32 Cole MG. Delirium: effectiveness of systematic interventions. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:406-411.

33 Marcantonio E, Ta T, Duthie E, et al. Delirium severity and psychomotor types: their relationship with outcomes after hip fracture repair. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:850-857.

34 Levkoff SE, Evans DA, Liptzin B, et al. Delirium. The occurrence and persistence of symptoms among elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:334-340.

35 McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, et al. The course of delirium in older medical inpatients: a prospective study. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:696-704.

36 Rockwood K, Cosway S, Carver D, et al. The risk of dementia and death after delirium. Age Ageing. 1999;28:551-556.

37 Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Elie LM. Delirium: prevention, treatment, and outcome studies. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1998;11:126-137.

38 Meagher DJ. Delirium: optimising management. BMJ. 2001;322:144-149.

39 Curyto KJ, Johnson J, TenHave T, et al. Survival of hospitalized elderly patients with delirium: a prospective study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:141-147.

40 Jeffs K, Lim W, Berlowitz D, et al: Delirium in a culturally diverse medical inpatient population. Poster 4 presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting—Australian Society for Geriatric Medicine, Fremantle, Western Australia, April 2004.

41 Francis J. Outcomes of delirium: can systems of care make a difference? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:247-248.

42 Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, et al. Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three-site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:234-242.

43 O’Keeffe S, Lavan J. The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospital patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:174-178.

44 McCusker J, Cole MG, Dendukuri N, et al. Does delirium increase hospital stay? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1539-1546.

45 Pompei P, Foreman M, Rudberg MA, et al. Delirium in hospitalized older persons: outcomes and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:809-815.

46 Stevens LE, de Moore GM, Simpson JM. Delirium in hospital: does it increase length of stay? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32:805-808.

47 Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor WN. A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1990;263:1097-1101.

48 Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, et al. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:474-481.

49 Brauer C, Morrison RS, Silberzweig SB, et al. The cause of delirium in patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1856-1860.

50 Rudberg MA, Pompei P, Foreman MD, et al. The natural history of delirium in older hospitalized patients: a syndrome of heterogeneity. Age Ageing. 1997;26:169-174.

51 Webster R, Holroyd S. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in delirium. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:519-522.

52 Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275:852-857.

53 McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Environmental risk factors for delirium in hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1327-1334.

54 Clary G, Ranga Krishnan K. Delirium: diagnosis, neuropathogenesis, and treatment. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7:310-323.

55 Flacker JM, Lipsitz LA. Neural mechanisms of delirium: current hypotheses and evolving concepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B239-B246.

56 Tune L, Carr S, Cooper T, et al. Association of anticholinergic activity of prescribed medications with postoperative delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;5:208-210.

57 Granacher RP, Baldessarini RJ, Messner E. Physostigmine treatment of delirium induced by anticholinergics. Am Fam Physician. 1976;13:99-103.

58 Trzepacz PT, Ho V, Mallavarapu H. Cholinergic delirium and neurotoxicity associated with tacrine for Alzheimer’s dementia. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:299-301.

59 Fischer P. Successful treatment of nonanticholinergic delirium with a cholinesterase inhibitor. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:118.

60 Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:231-237.

61 Platt MM, Breitbart W, Smith M, et al. Efficacy of neuroleptics for hypoactive delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:66-67.

62 Basile AS, Jones EA, Skolnick P. The pathogenesis and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: evidence for the involvement of benzodiazepine receptor ligands. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:27-71.

63 Jones EA, Skolnick P, Gammal SH, et al. NIH conference. The gamma-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA) receptor complex and hepatic encephalopathy. Some recent advances. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:532-546.

64 Olsson T. Activity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:345-349.

65 Hodges J. Cognitive Assessment for Clinicians. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999.

66 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

67 Rockwood K, Bhat R. Should we think before we treat delirium? Intern Med J. 2004;34:76-78.

68 Armstrong SC, Cozza KL, Watanabe KS. The misdiagnosis of delirium. Psychosomatics. 1997;38:433-439.

69 Farrell KR, Ganzini L. Misdiagnosing delirium as depression in medically ill elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2459-2464.

70 Nicholas LM, Lindsey BA. Delirium presenting with symptoms of depression. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:471-479.

71 Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Int Med. 1990;113:941-948.

72 Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, et al. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2467-2473.

73 Britton A, Russell R. Multidisciplinary team interventions for delirium in patients with chronic cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2004. CD000395.

74 Cole MG, Primeau F, McCusker J. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent delirium in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. CMAJ. 1996;155:1263-1268.

75 Inouye SK, Bogardus STJr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669-676.

76 Inouye SK, Bogardus STJr, Baker DI, et al. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697-1706.

77 Young LJ, George J. Do guidelines improve the process and outcomes of care in delirium? Age Ageing. 2003;32:525-528.

78 Tabet N, Hudson S, Sweeney V, et al. An educational intervention can prevent delirium on acute medical wards. Age Ageing. 2005;34:152-156.

79 Seibert CP. Recognition, management, and prevention of neuropsychological dysfunction after operation. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1986;24:39-58.

80 Gustafson Y, Brannstrom B, Berggren D, et al. A geriatricanesthesiologic program to reduce acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:655-662.

81 Flacker JM, Marcantonio ER. Delirium in the elderly. Optimal management. Drugs Aging. 1998;13:119-130.

82 Ebersole J, Pedley T. Current Practice of Clinical Electroencephalography, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

83 Harper C, Sheedy D, Lara A, et al. Prevalence of WernickeKorsakoff syndrome in Australia: has thiamine fortification made a difference? Med J Austr. 1998;168:542-545.

84 Cole MG, McCusker J, Bellavance F, et al. Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of delirium in older medical inpatients: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2002;167(7):753-759.

85 Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bailey RF, et al. Systematic intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 1994;151:965-970.

86 Weber JB, Coverdale JH, Kunik ME. Delirium: current trends in prevention and treatment. Intern Med J. 2004;34:115-121.

87 Webster JR, Chew R, Mailliard L, et al. Improving clinical and cost outcomes in delirium: use of practice guidelines and a delirium care team. Ann Long Term Care. 1999;7:128-134.

88 Lundstrom M, Edlund A, Karlsson S, et al. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:622-628.

89 Naughton BJ, Saltzman S, Ramadan F, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce prevalence of delirium and shorten hospital length of stay. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:18-23.

90 Flaherty JH, Tariq SH, Raghavan S, et al. A model for managing delirious older inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1031-1035.

91 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5, Suppl):1-20.

92 Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1405-1412.

93 Darzins P, Molloy D, Strang D. Who can decide? The six step capacity assessment process. Adelaide, Australia: Memory Australia Press, 2000.

94 Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286:2703-2710.

95 Roberts B, Rickard C, Rajbhandari D, et al. Multicentre study of delirium in ICU patients using a simple screening tool. Aust Crit Care. 2005;18:6-14.

96 Johnson JC, Kerse NM, Gottlieb G, et al. Prospective versus retrospective methods of identifying patients with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:316-319.

97 Marcantonio ER, Michaels M, Resnick NM. Diagnosing delirium by telephone. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:621-623.

98 Edlund A, Lundstrom M, Brannstrom B, et al. Delirium before and after operation for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1335-1340.

99 Zakriya KJ, Christmas C, Wenz JFSr, et al. Preoperative factors associated with postoperative change in confusion assessment method score in hip fracture patients. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1628-1632.

100 Shigeta H, Yasui A, Nimura Y, et al. Postoperative delirium and melatonin levels in elderly patients. Am J Surg. 2001;182:449-454.

101 Dai YT, Lou MF, Yip PK, et al. Risk factors and incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly Chinese patients. Gerontology. 2000;46:28-35.