Chapter 30 Degenerative Spine Disease

• Degeneration in the spine is a naturally occurring process that can be understood through the “three-joint complex,” which is composed of the intervertebral disk and the two dorsal articulating joints. Degeneration of any one joint leads to degeneration of the other two, initiating a cascade that leads to spinal degenerative disease.

• A detailed history and neurological examination can be used to isolate the level at which the underlying disease originate. Understanding the presenting symptoms can help to understand the degree of degeneration present and then start to formulate the most efficient treatment plan.

• Conservative treatment is a feasible first course of action to treat the clinical manifestations of first-onset degenerative spine disease. The most commonly accepted modalities range from anti-inflammatory therapy to exercises designed to increase muscle strength and relieve joint loading.

• Surgical intervention to treat symptoms that result from degenerative spine disease include diskectomy, laminectomy, and fusion procedures. Despite continuing controversy surrounding which procedure is most effective in providing long-term relief, the authors believe that the best course is to understand the underlying disease and select the least invasive procedure to target that pathological area.

• Fusion remains a heavily debated topic. Multiple studies have been performed to evaluate the benefits of fusion in the spine, none of which have provided definitive class I evidence to indicate a clear benefit. However, in addition to the class II and III evidence showing some benefit in selected patients, spine fusions may be indicated based on the need to create stability in an unstable region of the spine.

Back pain is the one of the most common reasons for primary care physician outpatient visits in the United States. A survey performed in 2002 reported that approximately 26% of Americans had low back pain and 14% had neck pain.1 In 2002, 890 million office visits were due to back pain. As may be expected from these statistics, the cost associated with the diagnosis and treatment of spine-related problems is astronomical. The Journal of the American Medical Association reported $86 billion in health expenditures in 2005 devoted to spine-related problems. This amount was an increase of 65% from 1997.2

Anatomy and Physiology of Spine Degeneration

Three-Joint Complex

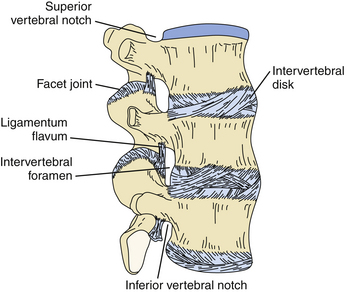

The Kirkaldy-Willis three-joint complex theory deconstructs the spine into three joints that are affected in the degenerative process. At each level of the spine there exists the “three-joint complex,” composed of the intervertebral disk and two dorsal zygapophyseal joints.3 Kirkaldy-Willis proposed that the three joints are linked, in that degeneration of one joint leads to degeneration of the other two joints, and ultimately results in the global manifestations of degenerative spine disease (Fig. 30.1).

Disk Degeneration

The intervertebral disk has three components: the nucleus pulposus, which is surrounded by the annulus fibrosis, and the cartilaginous end plates.4 The nucleus pulposus is a semigelatinous structure situated near the center of the disk complex. It is a remnant of the notochord and is composed mainly of mucopolysaccharides with salt and water. The surrounding annulus fibrosis is a multilayered circular structure that surrounds the nucleus pulposus. It is composed of fibrocartilaginous lamellae and is stiffer than the nucleus. It is usually thicker ventrally than dorsally.4

The process of disk degeneration is a part of the natural aging process. Repetitive loading results in forces that foster degeneration. As part of the normal aging process, the intervertebral disk becomes desiccated as collagen and proteoglycans are replaced with fibrous tissue. As axial pressure continues to be repetitively applied to the disk, the less compliant annulus fibrosis develops circumferential tears that are most frequently observed in the dorsolateral aspect of the annulus.5 These tears can enlarge and eventually develop into radial tears. These tears are areas through which the nucleus pulposus may herniate. Since the nucleus pulposus is situated relatively dorsal in the disk space, herniation typically occurs dorsally into the spinal canal. The presence of the posterior longitudinal ligament forces disk herniations laterally. The aforementioned anatomical and biomechanical factors often lead to the common classical dorsolateral disk herniation.

Dorsal Joint Degeneration

The dorsal aspect of the intervertebral joint is composed of articulating facets from the superior and inferior vertebral segments. The joints are diarthrodial joints with articular cartilage, a synovial membrane, and a capsule.6 Studies have shown that natural aging of the dorsal joints passes through a progression that includes synovial reaction, fibrillation of the articular cartilage, osteophyte formation, and ultimately, laxity of the joint capsule. This inevitably results in instability of the joint complex and can lead to subluxation of the joint. Osteophytic formation from the joint protruding into the spinal canal can also contribute to stenosis, particularly in the lateral recesses of the spinal canal.

Three Stages of Degenerative Spine Disease

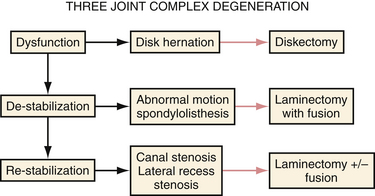

Using the three-joint complex as a basis for degenerative spine disease, Kirkaldy-Willis categorized the degeneration of the spine into three stages to rationalize the natural history of spine degeneration, as well as to provide an algorithm to tailor treatment for each stage (Fig. 30.2).

The Dysfunction Stage

The first stage is that of dysfunction. The clinical manifestations both clinically and physiologically are minor at this stage. This stage is characterized by synovial reaction in the dorsal joints and small tears in the intervertebral disks. Clinical symptoms present at this stage are typically minor or absent and are best treated conservatively.

Clinical Presentation

With cervical spine involvement, the patient often complains of a shooting pain that travels from the shoulder to the fingers. The exact location of the shooting pain can help to isolate the level of the disk herniation. Cervical disk herniations most often occur at the C5-C6 and C6-C7 levels.7 In the lumbar spine disk herniations most commonly occur at the L4-L5 interspace8 and manifest as shooting pain that often begins in the buttock region and passes down the legs, with or without extension into the feet. Once again, the distribution can help to localize the level of herniation. Thoracic disk hernations are much less common than cervical or lumbar disk herniations. In a study of 82 patients with thoracic disk herniations, 76% of the presenting complaints consisted of pain. Of the patient who presented with pain, 41% presented with localized back pain, thus relegating surgical management to the “precarious” category in most clinical cases.9

Further degeneration, resulting in further diffuse disk bulging into the spinal canal, combined with osteophyte formation from dorsal joint laxity and inflammation of the ligamentum flavum, can lead to circumferential spinal canal narrowing manifesting as neurogenic claudication. Neurogenic claudication manifests as pain that is exacerbated by walking or standing, and relieved with postural changes that allow increasing the diameter of the spinal canal or neural foramina. The affected patient often reports that pain is relieved when in the sitting position. Also, patients report that walking while leaning forward, often supporting their weight while pushing a shopping cart, allows for relief of back pain (“shopping cart sign”). An important distinction must be made between neurogenic claudication and vascular claudication. Vascular claudication is a result of vascular insufficiency and manifests as leg pain with motion that is relieved by rest. It is important to properly assess the vascular supply by inspecting distal pedal pulses in order to differentiate between the two entities. In addition, other clinical observations may be used to differentiate the two diagnoses. For example, pushing a shopping cart (i.e., “shopping cart sign”) does not relieve vascular claudication symptoms. Other manifestations of vascular disease should be sought as well, including loss of foot/toe hair, skin discoloration, and a clinical history of other disorders and risk factors associated with ischemic vascular disease.

Diagnostic Findings

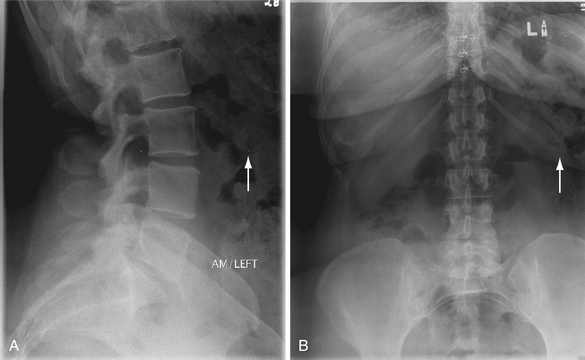

The initial evaluation of back and leg pain begins with static plain radiographs (Fig. 30.3). Static radiographs provide an evaluation of spinal alignment and the intervertebral disk spaces. An assessment of an affected intervertebral space serves to provide a rough estimation of the extent of disk degeneration, and therefore desiccation, that is present at a given level. Static radiographs consisting of flexion and extension views of the cervical or lumbar spine can reveal loss of normal alignment during motion. Such may be indicative of dorsal, or even ventral, joint instability.

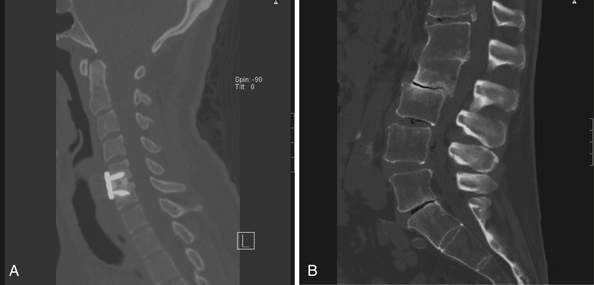

Computed tomography (CT) provides a very useful evaluation of the bony anatomy (Fig. 30.4). CT is effective in evaluating for bony osteophytes, presence of calcification, and dimensions of bony architecture that may be required for surgical planning. CT myelography is an effective alternative to assess the neural elements when magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is either contraindicated (due to medical implants) or would be less efficacious owing to artifact from previous instrumentation. CT myelography can detect central as well as foraminal stenosis.

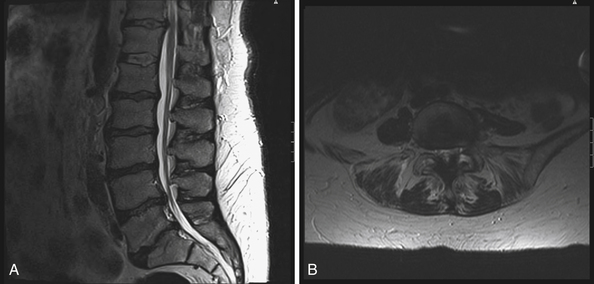

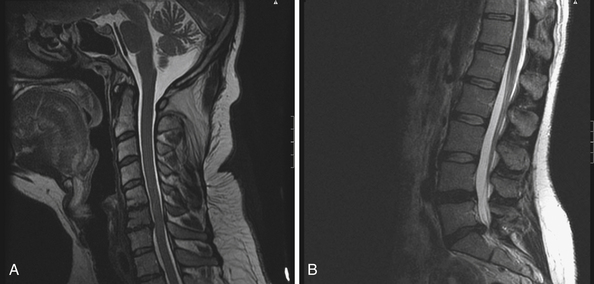

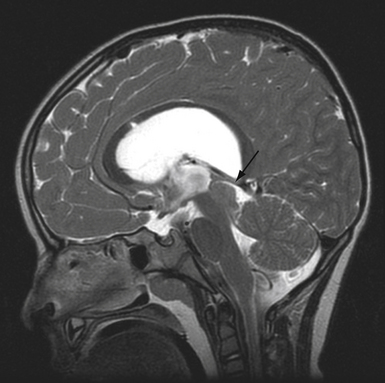

MRI is widely considered the gold standard for the imaging evaluation of spinal canal stenosis (Fig. 30.5). MRI can most effectively visualize the soft tissues surrounding the spinal canal, as well as the intervertebral disks, ligamentum flavum, and facet joints. In degenerative spine disease, the location of disk herniation can be evaluated. The origin of the spinal canal stenosis, whether from the intervertebral disks, hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament or of the ligamentum flavum, or facet hypertrophy, can be specifically localized by MRI.

Diskography is a more invasive diagnostic strategy. At times, when the clinical presentation does not match the findings on the aforementioned routine imaging techniques, or indeterminate findings on standard imaging modalities are present, some feel that diskography may be used to identify and characterize the disease. Diskography involves injecting contrast material into the intervertebral disks in question. The amount of contrast agent tolerated by a disk is an indication of degeneration. A normal cervical disk may tolerate 0.2 to 0.5 mL of fluid, whereas a degenerated disk can accept 0.5 to 1.5 mL of fluid.10 If the pain produced following contrast injection is concordant with the typical pain experienced by the patient, the injected level is considered by some to be the pathological segment. Disk pressure at which pain is elicited is also used to predict the pathological level, because damaged disks allegedly produce pain at lower pressures than normal disks.11 The effectiveness of diskography to predict positive surgical outcomes is controversial at best, with varying predictive reliability. One of the greatest criticisms of diskography is that the grading system employs a subjective criterion for pain, and therefore can be skewed, depending on the patient and the examiner. It is emphasized that diskography should be used with the understanding that it does not provide clinically proven diagnostic utility.

Treatment Options

Nonoperative Management

Conservative management plays a significant role in the management of degenerative spine disease. Studies of the natural course of spinal stenosis have shown that up to 47% of patients with symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis, including neurogenic claudication and radiculopathy, had improvement of symptoms without any intervention.12 Although the physiology of spontaneous improvement of symptoms of spinal stenosis is unclear, it has been postulated that progressive disk dehydration may lead to shrinking of the disk and a decrease in nerve root compression.13

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications have been shown to be effective in providing relief for acute back pain.14 Narcotic medication can be used to supplement those drugs when there is more severe pain, but the effectiveness of narcotics only serves to mask the degenerative process until it progresses or improves spontaneously. Furthermore, narcotic medications often contribute to the perpetuation of the cyclical process leading to the development of a chronic pain syndrome in patients who do not improve. Their use, therefore, should be very carefully considered.

Other medical treatments include muscle relaxants. Muscle relaxants have shown benefit for the treatment of acute neck and back pain.15 Systemic oral steroids have also been utilized for the treatment of radicular pain. Some think that the anti-inflammatory effects may reduce nerve root irritation, although several studies have not demonstrated a proven clinical effect.16–18

Facet joint injections remain a controversial mode of treatment for back pain. Injections are composed of a long-acting local anesthetic, combined with steroids. Studies have reported no evidence of clinical improvement of back pain,19 with only 33% of patients reporting greater than a 50% relief of pain.20 This approximates results that are consistent with the placebo effect. The key to the efficacy of facet injections may reside in the proper selection of patients with the so-called facet syndrome. Lippitt defined the manifestations of the facet syndrome as “pain in the hips and buttocks area, cramping thigh pain, and back stiffness that is worse in the morning, without lower extremity paresthesias.” One of the alleged key signs associated with the facet syndrome is the observation that the pain is exacerbated with lumbar spine extension.21 A factor that may confound the efficacy of facet joint injections is the likelihood that injected material may leak out of the facet joint. This leaking may result in direct nerve root block or diffusion of anesthetic material into the paraspinous soft tissues. Such “leakage” would obviously skew outcomes. Nevertheless, facet joint injection persists as a popular therapeutic and diagnostic modality.

One of the less understood therapies patients have often attempted prior to their presentation to a spine specialist is spinal manipulative therapy (SMT). SMT is primarily provided by chiropractors, but can also be administered by physical therapists and osteopathic physicians. Manipulation can be categorized into three main types of therapies: therapeutic massage, mobilization, and manipulative procedures. These manipulation techniques range from the application of pressure isolated to the paraspinal musculature to maneuvers that stress the spinal joints and ligaments. The therapeutic benefit of SMT stems from the hypothesis that neck or back pain is caused by either a limited range of motion or abnormal dorsal intervertebral joint motion. A natural joint motion consists of an active range of motion, followed by a passive range of motion that can be reached with external mobilization. A dysfunctional joint leads to pain because it is unable to reach the entire range of motion. SMT “resets” the joint by extending the joint beyond the passive range of motion, into the “paraphysiological range of motion.” This stresses the joint to its limit, just short of joint disruption. At this point, joint cavitation occurs, and the often encountered sounds of joint mobilization, which are likely the result of gas released into the joint space,22 occur. The effectiveness of spinal manipulation has been questioned, and definitive clinical studies that show significant long-term improvement are lacking. Clinical evidence indicates that there may be short-term relief for the management of low back pain, but there is no evidence of significance that demonstrates efficacy.23 One of the difficulties associated with assessing the effectiveness of SMT is related to the fact that there exists no universal treatment strategy—the types and numbers of treatments administered vary most dramatically across the board.

Operative Treatment

In the initial stage of spinal degeneration, disk desiccation leads to predominantly dorsolateral disk herniations causing radicular symptoms (Fig. 30.6). Single-level disk herniations can be treated nonoperatively or with cervical or lumbar diskectomy. The latter are relatively “simple” operations that are associated with a relatively high degree of short-term success. Long-term success is more variable.

Diskectomy

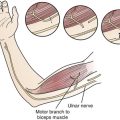

Diskectomy procedures can be typically categorized into ventral and dorsal approaches. In the cervical spine, the ventral approach is often utilized because of its ability to decompress broad-based disk herniations. The ventral approach is performed through a paramedian incision that requires little muscle splitting, which leads to a relatively low amount of postoperative pain and morbidity. The most commonly encountered postoperative complication is dysphagia secondary to retraction of the esophagus, which has been shown to occur in anywhere from 1% to 79% of cases following anterior cervical procedures, but dramatically improves in the majority of cases.24 The other main consideration of the ventral cervical approach, and possibly a contraindication to the approach, is damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve resulting in vocal cord paralysis. This paralysis has also been shown to improve with time in the majority of cases25 (Fig. 30.7).

The dorsal approach to the cervical spine has also been shown to be effective in eliminating unilateral nerve root compression. The technique is effective for eliminating posterolateral disk herniations either through foraminotomies with or without a diskectomy procedure. The dorsal approach eliminates the morbidity associated with the ventral approach, mainly dysphagia, and risk to the ventral neurovascular structures, but requires muscle splitting, which can add a variable amount of postoperative pain. Simple foraminotomies and diskectomies also do not require fusion, theoretically decreasing risk of adjacent segment degeneration. Minimally invasive techniques have been developed to reduce the amount of muscle dissection carried out and have shown to have up to a 97% success rate alleviating radiculopathy symptoms.26

Diskectomy procedures in the lumbar spine can also be categorized into anterior and posterior approaches, although unlike the cervical spine, the posterior approach is the more often utilized. Lumbar diskectomies involve a unilateral muscle dissection exposing the lamina of the given level to allow a hemilaminectomy, through which the herniated disk is removed. The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) was a prospective, randomized trial that evaluated lumbar diskectomies against nonoperative treatment.27 This trial concluded that patients undergoing lumbar diskectomies enjoyed reduction of pain, improvements in physical functioning, and a greater improvement in their disability index than patients undergoing conservative treatment. Given the presence of the cauda equina in the lumbar region as opposed to the spinal cord present in the cervical region, the posterior approach is more versatile in the sense that even more centralized disk herniations can be decompressed owing to the amount of manipulation that can be tolerated by the thecal sac.

Laminectomy

Laminectomies decompress the spine via the removal of the lamina and spinous process. Laminectomy can be applied equally in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, typically for multilevel reduction of spinal canal stenosis. In the cervical spine, multilevel laminectomy has been shown to be effective particularly for canal decompression resulting in cervical spondolytic myelopathy, as well as for other pathological disorders such as ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Although shown to be effective in improving signs of myelopathy, the development of postoperative kyphosis has been reported to be between 14% and 47%.28 This has led to the use of cervical laminectomy combined with fusion and laminoplasty. Although all three techniques have been shown to be effective in decompressing the spinal canal, laminectomy with fusion and laminoplasty have become more commonplace owing to their reduced incidence of postoperative kyphosis.

Laminoplasty involves detachment of the lamina on only one side by creating a trough, and thinning the lamina on the contralateral side to allow for “hinging” at the attached lamina site. This allows the detached lamina to be elevated and secured using small bone grafts to maintain the decompressed state. The preservation of the posterior elements has been shown to effectively decompress the spinal canal without the consequences of fusion such as loss of range of motion and adjacent segment degeneration. In one study, laminoplasty was shown to be associated with a 27% improvement in preventing the incidence of postoperative kyphosis.29

Fusion

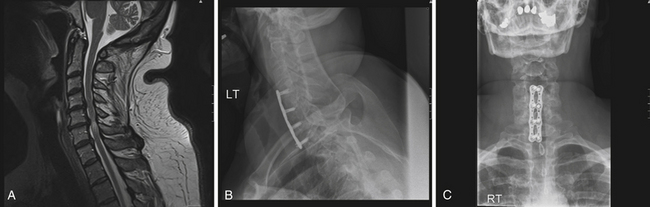

Fusion remains a heavily debated topic. Multiple studies have been performed to evaluate the benefits of fusion in the spine, none of which has provided definitive class I evidence to indicate a clear benefit. The consideration to perform a fusion is typically based on the need to create stability in an unstable region of the spine. In the cervical spine, fusion can be considered for ventral and dorsal approaches. A review of 13 class II and III studies comparing the outcome of anterior cervical diskectomies with and without fusion performed by Matz and associates, demonstrated that there was no clinically significant advantage of including fusion. Only two class III studies demonstrated that anterior cervical diskectomy alone had a short length of hospital stay and operative time.30 Fusion has become a commonplace procedure with cervical laminectomies owing to the incidence of postoperative kyphosis (Fig. 30.8). Although no class I or II evidence exists to support the use of cervical laminectomy with fusion, there is class III evidence to indicate that fusion reduces postoperative kyphosis.28,31,32

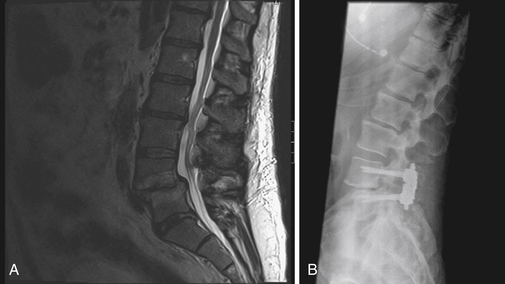

A great deal of controversy surrounds the indications for fusion in the lumbar spine. The indication for fusion is typically during the end of the second stage of the Kirkaldy-Willis process, which is the phase of maximal destabilization. Degeneration of the joint complexes and disk space leads to excessive movement of one vertebral body upon another, creating mechanical back pain. The pain created is partially axial pain caused by disk degeneration and abnormal joint motion but can also have a radicular component due to foraminal stenosis and nerve root entrapment during mobility. Lumbar fusion can be used to augment the transition to the second stage of spinal degeneration into the third stage, restabilization. Fusion typically involves a laminectomy to decompress the spinal canal and the lateral recess (Fig. 30.9). Autograft bone is used either in the dorsolateral spaces or the interspaces to facilitate bony fusion while the construct immobilizes the spinal segment. There are no clear data to support the presumption that fusion results in better outcomes compared to simple laminectomy alone. A multicenter trial is currently underway to compare fusion with laminectomy alone for grade I spondylolisthesis.33

Ghogawala Z. Spinal laminectomy vs. instrumented pedicle screw fusion. Available at http://www.spine-slip-study.org/2

Johnsson K.E., Rosen I., Uden A. The natural course of lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;279:82-86.

Ritchie J.H., Fahrni W.H. Age changes in lumbar intervertebral discs. Can J Surg. 1970;13(1):65-71.

Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis: four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine. 2010;35(14):1329-1338.

Yong-Hing K., Kirkaldy-Willis W.H. The pathophysiology of degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14(3):491-504.

Please go to expertconsult.com to view the complete list of references.

1. Deyo R.A., Mirza S.K., Martin B.I. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31(23):2724-2727.

2. Martin B.I., Deyo R.A., Mirza S.K., et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299:656-664.

3. Yong-Hing K., Kirkaldy-Willis W.H. The pathophysiology of degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14(3):491-504.

4. Coventry M.B. Anatomy of the intervertebral disk. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;67:9-15.

5. Ritchie J.H., Fahrni W.H. Age changes in lumbar intervertebral discs. Can J Surg. 1970;13(1):65-71.

6. Kirkaldy-Willis W.H., Wedge J.H., Yong-Hing K., Reilly J. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine. 1978;3(4):319-328.

7. Dubuisson A., Lenelle J., Stevenart A. Soft cervical disc herniation: a retrospective study of 100 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;125(1-4):115-119.

8. Kortelainen P., Puranen J., Koivisto E., Lahde S. Symptoms and signs of sciatica and their relation to the localization of the lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1985;10:88-92.

9. Stillerman C.B., Chen T.C., Couldwell W.T., et al. Experience in the surgical management of 82 symptomatic herniated thoracic discs and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;88(4):623-633.

10. Anderson M.W. Lumbar discography: an update. Semin Roentgenol. 2004;39(1):52-67.

11. Derby R., Howard M.W., Grant J.M., et al. The ability of pressure-controlled discography to predict surgical and nonsurgical outcomes. Spine. 1999;24(4):371-372.

12. Johnsson K.E., Rosen I., Uden A. The natural course of lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;279:82-86.

13. Henmi T., Sairyo K., Nakano S., et al. Natural history of extruded lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. J Med Invest. 2002;49(1-2):40-43.

14. Roelofs P.D., Deyo R.A., Koes B.W., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33(16):1766-1774.

15. McCarberg B.H. Acute back pain: benefits and risks of current treatments. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):179-190.

16. Finckh A., Zufferey P., Schurch M.A., et al. Short-term efficacy of intravenous pulse glucocorticoids in acute discogenic sciatica. A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2006;31:377-381.

17. Friedman B.W., Holden L., Esses D., et al. Parenteral corticosteroids for emergency department patients with non-radicular low back pain. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:365-370.

18. Haimovic I.C., Beresford H.R. Dexamethasone is not superior to placebo for treating lumbosacral radicular pain. Neurology. 1986;36:1593-1594.

19. Nelemans P.J., deBie R.A., deVet H.C., et al. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic benign low back pain. Spine. 2001;26(5):501-515.

20. Gorabach C., Schmid M.R., Elfering A., et al. Therapeutic efficacy of facet joint blocks. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(5):1228-1233.

21. Lippitt A.B. The facet joint and its role in spine pain. Management with facet joint infections. Spine. 1984;9(7):746-750.

22. Herzog W., Zhang Y.T., Conway P.J., et al. Cavitation sounds during spinal manipulative treatments. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16:523-526.

23. Swenson R., Haldeman S. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. J Am Aca Orthop Surg. 2003;11(4):228-237.

24. Riley L.H.3rd, Vaccaro A.R., Dettori J.R., et al. Postoperative dysphagia in anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2010;35(9 Suppl):S76-S85.

25. Fountas K.N., Kapsalaki E.Z., Nikolakakos L.G., et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine. 2007;32(21):2310-2317.

26. Gala V.C., O’Toole J.E., Voyadzis J.M., et al. Posterior minimally invasive approaches for the cervical spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(3):339-349.

27. Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis: four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine. 2010;35(14):1329-1338.

28. Ryken T.C., Heary R.F., Matz P.G., et al. Cervical laminectomy for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(2):142-149.

29. Matsunaga S., Sakou T., Nakanisi K. Analysis of the cervical spine alignment following laminoplasty and laminectomy. Spinal Cord. 1999;37(1):20-24.

30. Matz P.G., Ryken T.C., Groff M.W., et al. Techniques for anterior cervical decompression for radiculopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(2):183-197.

31. Matz P.G., Anderson P.A., Groff N.W., et al. Cervical laminoplasty for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. 2009;11(2):157-169.

32. Anderson P.A., Matz P.G., Groff M.W., et al. Laminectomy and fusion for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(2):15-156.

33. Ghogawala Z. Spinal laminectomy vs. instrumented pedicle screw fusion. Available at http://www.spine-slip-study.org/2