5 Deformities and congenital disorders

Deformities may be congenital or acquired, and they may reflect an underlying abnormality of bone, joint, or soft tissue.

CONGENITAL DEFORMITIES

Congenital deformities or malformations, by definition, are attributable to faulty development and are present at birth, though they may not be recognised until later. They vary from severe malformations that are incompatible with life and may be found in still-born infants, to minor abnormalities of structure that have no practical significance. Incidence varies in different countries and among different races: in Britain probably 2 or 3% of infants are born with some significant developmental abnormality, but only about half of these affect the musculo-skeletal system. Some of the better-known anomalies are summarised in Table 5.1 (p. 53).

Table 5.1 Some of the better-known congenital deformities or anomalies of orthopaedic interest, with their salient clinical features. (When a fuller description appears elsewhere in this book the relevant page number is given. Conditions not thus designated are either so rare or of such little importance to the student that further description is unnecessary.)

| Name of deformity or anomaly | Clinical or pathological features |

|---|---|

| Generalised | |

| Osteogenesis imperfecta (fragilitas ossium) (p. 62) | Fragile soft bones, easily broken or deformed. Often blue sclerotics. Joint laxity. Otosclerosis |

| Diaphysial aclasis (multiple exostoses) (p. 63) | Cartilage-capped bony outgrowths from metaphyses. Deficient remodelling. Stunted growth |

| Dyschondroplasia (multiple chondromatosis; Ollier’s disease) (p. 65) | Masses of cartilage in metaphyses of long bones. Impaired growth. Deformity. Often unilateral |

| Achondroplasia (chondro-dystrophy) (p. 61) | Short-limb dwarfing from defective growth of long bones. Trident hand. Large head |

| Osteopetrosis (Albers–Schönberg disease; ‘marble bones’) | Hard dense bones, but with increased liability to fracture. Anaemia from obliteration of medulla |

| Gargoylism (Hurler’s syndrome) | Dwarfing. Kyphosis from deformed vertebrae. Corneal opacity. Large liver and spleen. Mental deficiency |

| Cranio-cleido dysostosis (p. 71) | Impaired ossification of skull. Deficient clavicles. Often deficient symphysis pubis |

| Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (amyoplasia congenita) | Stiff deformed limb joints from defective development of muscles, usually secondary to nerve cell deficiency though a type due to primary dysplasia of muscle is also recognised. Hips often dislocated. Club feet |

| Pseudohypertrophic muscular dystrophy | Genetic transmission to boys through female carriers. Progressive muscle weakness evident at age 3–6 years. Raised urinary creatine phosphokinase: carriers may thus be identified. The defect may be diagnosed in early pregnancy, when abortion may be advised |

| Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (p. 71) | Ectopic ossification, often beginning in trunk but extending to limbs. Short great toe |

| Familial hypophosphataemia (p. 76) | Rachitic bone changes corrected only by massive doses of vitamin D. Hypophosphataemia not responsive to vitamin D |

| Cystinosis (renal tubular rickets) (p. 78) | Rachitic rarefied bones with consequent deformity. Hypophosphataemia. Glycosuria; amino-aciduria |

| Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) (p. 70) | Café au lait areas or spots. Cutaneous fibromata. Neurofibromata on cranial or peripheral nerves. Often scoliosis. Occasionally, overgrowth of bone |

| Haemophilia (p. 145) | Prolonged blood clotting time from deficiency of Factor VIII. Bleeding into joints or soft tissue |

| Gaucher’s disease (p. 72) | Deposition of kerasin in reticulum cells, causing cyst-like appearance in bones, and large liver and spleen |

| Down’s syndrome (mongolism) | Mental and physical impairment from trisomy of chromosome 21, giving 47 instead of 46 chromosomes |

| Trunk and spine | |

| Congenital short neck (Klippel–Feil syndrome) (p. 188) | Short stiff neck with low hair-line. Fused or deformed cervical vertebrae |

| Congenital high scapula (Sprengel’s shoulder) (p. 189) | Scapula tethered high up, usually only on one side. Scapular movement impaired |

| Cervical rib (p. 202) | Often symptomless. Vascular symptoms (partial ischaemia) or nerve symptoms (paraesthesiae, lower trunk paresis) |

| Hemivertebra (congenital scoliosis) (pp. 213, 218) | Defective development of vertebra (and often of adjacent structures) on one side. Scoliosis |

| Spina bifida (spinal dysraphism) (p. 171) | Spina bifida occulta, meningocele or myelocele. Often leg deformities from paralysis or muscle imbalance. Often incontinence. Often associated hydrocephalus. Diagnosable in early pregnancy from excess of alpha-fetoprotein in urine and amniotic fluid |

| Limbs | |

| Congenital arterio-venous fistula | Hypertrophy and lengthening of limb. Bruit |

| Congenital amputation | Part or whole of one or more limbs absent |

| Phocomelia | Aplasia of proximal part of limb, the distal part being present (‘seal-limb’). Diagnosable in pregnancy by ultrasonography |

| Constriction rings | Limb or digit constricted as if by a tight string. May be associated with syndactyly |

| Absence of radius (radial club hand) | Hand deviated laterally from lack of normal support by radius. Thumb often absent |

| Absence of thumb | Thumb alone may be absent, but other deformities may co-exist |

| Absence of proximal arm muscles | Trapezius, deltoid, sternomastoid, or pectoralis major absent |

| Radio-ulnar synostosis | Forearm bones fused at proximal ends, preventing rotation |

| Madelung’s deformity (dyschondrosteosis) (p. 303) | Head of ulna dislocated dorsally from lower end of radius. Radius bowed |

| Syndactyly | Webbing of two or more digits |

| Polydactyly | More than five digits |

| Ectrodactyly | Lobster-claw appearance of hand, with pincer grip |

| Congenital dislocation of hip (p. 343) | Neonatal: diagnostic click obtainable. Later infancy: shortening; limited abduction. Radiographs diagnostic |

| Congenital coxa vara (p. 376) | Defective ossification of femoral neck, with reduced neck–shaft angle |

| Congenital short femur | Proximal end of femur deficient or rudimentary. Thigh short |

| Congenital tibial pseudarthrosis | Resembles ununited fracture in tibial shaft. Aetiology unknown, may be neurofibromatosis |

| Absence of fibula | Leg under-developed on outer side. Foot small and everted; lateral two or three digital rays may be absent |

| Congenital club foot (p. 434) | Foot inverted and plantarflexed (equino-varus), or everted and dorsiflexed (calcaneo-valgus) |

| Congenital curled toe (p. 458) | Lateral angulation of one or more toes. Toe may lie over or under adjacent toe |

CONGENITAL PSEUDARTHROSIS

Practical significance

Many of the recognised congenital abnormalities of the musculo-skeletal system have little practical importance, either because they are very rare or because there is little that can be done for them: these will not all be considered further in this book. There are others, however, that present major problems to the orthopaedic surgeon and may demand energetic treatment. These include developmental or congenital dislocation of the hip (p. 343), congenital club foot (p. 434), spina bifida (p. 171), congenital scoliosis (p. 218), osteogenesis imperfecta (p. 62), and cervical rib (p. 202).

Inborn predisposition to disease in adults

It is well recognised that, quite apart from the overt congenital anomalies discussed above, there exists in some patients a genetically determined predisposition to abnormalities developing in later life. Examples of orthopaedic conditions to which a susceptibility may exist include certain types of osteo-arthritis (especially of the hips), ankylosing spondylitis, gouty arthritis, rheumatic fever, idiopathic scoliosis, osteochondritis dissecans, and Dupuytren’s contracture.

ACQUIRED DEFORMITIES

DEFORMITY ARISING AT A JOINT

Causes

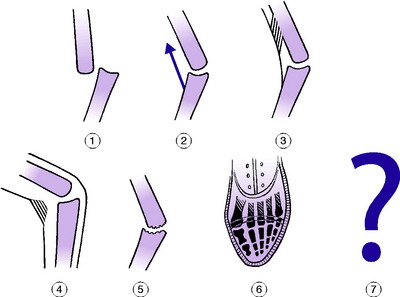

The causes of deformity arising at a joint may be summarised under the following headings (Fig. 5.1):

Dislocation or subluxation

This is usually caused by injury, but it may occur as a congenital deformity, or it may follow disease of the joint (pathological dislocation).

Muscle imbalance

Unbalanced action of muscles upon a joint may hold it continuously in a particular arc of its range. In time, secondary contractures occur in the dominant muscles or in the soft tissues, preventing the joint from returning to the neutral position (Fig. 5.1 (2)). The two fundamental causes of muscle imbalance are:

Thus equinus deformity at the ankle may follow paralysis of the dorsiflexor muscles (for instance, from damage to the lateral popliteal nerve) because the action of the plantarflexors and of gravity is unopposed. Or a similar deformity may be caused by spasticity of the calf muscles, which overpower their antagonists. This occurs commonly in cerebral palsy (p. 168).

Tethering or contracture of muscles or tendons

If something happens to muscles or tendons that prevents their normal to-and-fro gliding, or their elongation and retraction, the joint may be held in a position of deformity. Thus a muscle or tendon may be tethered to the surrounding tissues in consequence of local infection or injury (Fig. 5.1 (3)). An example is the anchoring of a flexor tendon of a finger within its fibrous sheath as a result of suppurative tenosynovitis, with consequent flexion deformity at the interphalangeal joints. Or a muscle may lose its elasticity and contractile power from impairment of its blood supply. An important example is Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture of the forearm flexor muscles (p. 299) from occlusion of the brachial artery or from increased intra-compartmental pressure, with consequent flexion deformity of the wrist and fingers.

Contracture of soft tissues

Apart from any disturbance of the muscles, contracture of other soft tissues alone can account for joint deformity. An example is the common condition of Dupuytren’s contracture (p. 321), in which the thickened and contracted palmar aponeurosis pulls the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of one or more fingers into flexion. Similarly, a flexion deformity of the knee or elbow, or indeed of any joint, may occur from contracture of the scarred skin after burns of the flexor surface of the limb (Fig. 5.1 (4)).

Arthritis

The various types of arthritis will be discussed in a later chapter. Any type of arthritis may lead to joint deformity. In some cases the joint is firmly fixed in a deformed position by bony or fibrous ankylosis. In other instances the joint retains some movement but is prevented from reaching the neutral position. Thus flexion and adduction deformity is common in osteoarthritis of the hip, flexion deformity is common in arthritis of the knee, and the deformity of ulnar deviation of the fingers (Fig. 16.11A, p. 305) is a well-known feature of rheumatoid arthritis of the metacarpo-phalangeal joints.

Posture

The habitual adoption of a deformed position of a joint often leads in time to permanent deformity. A common example is the lateral deviation of the great toe at the metatarso-phalangeal joint – hallux valgus – so common in women who cramp their feet into narrow pointed shoes (Fig. 5.1 (6)). Another postural deformity that is still seen occasionally – though it should never be allowed to occur – is fixed flexion of the knees in a patient confined to bed for a long time with the knees bent over a pillow.

Unknown causes

In some cases deformity occurs at a joint for no apparent reason. Thus many children develop knock-knee deformity between the ages of 3 and 5 years without demonstrable cause. It is usually unimportant because it tends to correct itself spontaneously. Another common and more serious example is the inversion deformity of the foot known as talipes equino-varus or congenital club foot. A more sinister deformity that is equally ill explained is the idiopathic scoliosis of adolescents (p. 215).

DEFORMITY ARISING IN A BONE

Deformity exists in a bone when it is out of its normal anatomical alignment.

Fracture

This is by far the most common cause. Unless a fracture is reduced so that the fragments are perfectly aligned, deformity will result. Examples are the genu valgum (knock knee) that is often the consequence of compression fractures of the lateral condyle of the tibia, the cubitus valgus that may follow displaced fractures of the lateral condyle of the humerus, and the common ‘dinner-fork’ deformity of an unreduced fracture of the lower end of the radius.

Congenital tibial pseudarthrosis may mimic an ununited fracture, but is often present at birth and may be linked to neurofibromatosis (seep. 70).

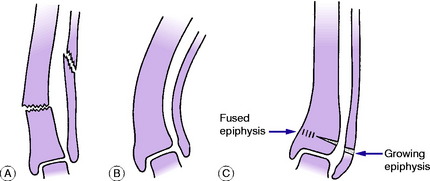

Uneven growth of bone

In children any disturbance of the growing epiphysial cartilage (growth plate) may lead to uneven growth and consequent deformity. The usual effect of interference with a growing epiphysial cartilage is that its growth is retarded; occasionally it is accelerated. Deformity will follow only if the growing cartilage is affected more in one part than another, or if the interference with growth affects only one bone of a pair, as in the forearm or leg (Fig. 5.2C). The most frequent causes of retarded epiphysial growth are: