CHAPTER 20 Deep plane procedures in the neck

Introduction

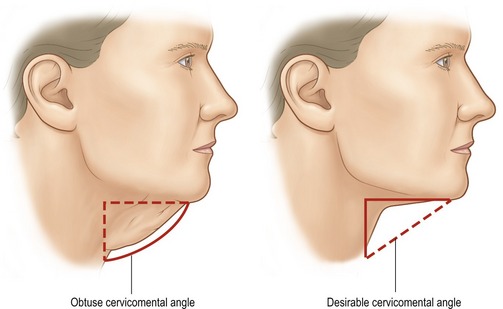

The cervicomental angle and the contours of the neck are very important determinants of facial aesthetics and are readily modified in facial rejuvenative surgery. Deep plane procedures in the neck are often required to reach the aesthetic endpoint of a defined, less obtuse cervicomental angle and smooth surface contours. Four structures are altered in deep plane procedures of the neck: the platysma, subplatysmal fat, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the submandibular gland. Deep plane procedures involving these structures are most effective when employed in concert with other rejuvenation efforts in the superficial structures of the neck and the remainder of the face. With that in mind, this chapter focuses on deep plane procedures and how they are integrated into a global approach to cervicofacial rejuvenation.

Physical evaluation

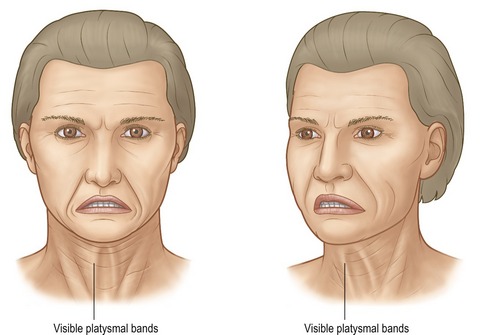

• The first step in evaluation for the neck is a visual inspection. The front view is helpful in identifying platysmal bands and the lateral view permits assessment of the configuration of the cervicomental angle (Fig. 20.1).

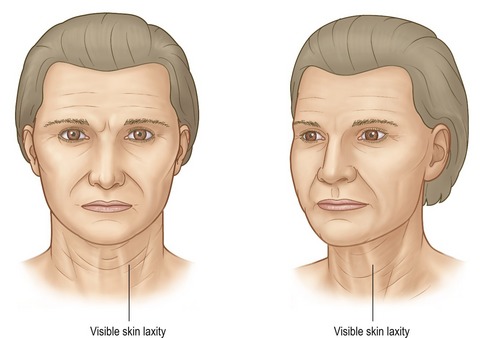

• Visual inspection and palpation are performed to assess skin quality and skin excess. Sun-damaged skin, inelastic skin and skin with a crepe-like quality will likely require more excision in the postauricular region to facilitate envelope redraping (Fig. 20.2).

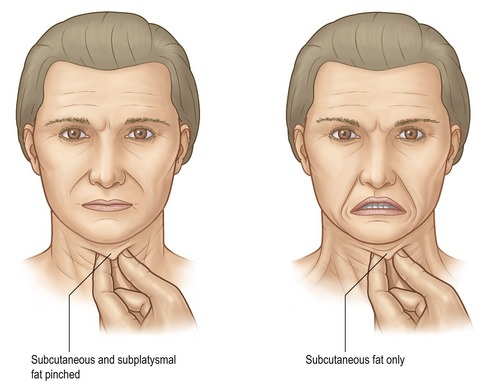

• The patient is instructed to flex her platysma muscle to accentuate the visibility of bands (Fig. 20.3). The submental region is palpated with the thumb in opposition to the fore and long fingers before and after activation of the platysma in order to differentiate subplatysmal bulk (anterior belly of the digastric muscle and fat) from preplatysmal fat (Fig. 20.4).

• With the head in the neutral position (Frankfort horizontal parallel to the ground) the bulk in the region of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle is visualized and palpated.

• Thyroid cartilage position and prominence are noted and are important to consider in female patients in whom a platysmal myotomy is planned. The myotomy is planned sufficiently low (2 cm below the cartilage) so that the thyroid cartilage prominence is not unmasked, thus producing a masculine appearance.

• The submandibular triangle is inspected by palpation for a discrete firm mass that can often be balloted against the medial and/or caudal surface of the body of the mandible. When such a mass is appreciated, the submandibular gland is hypertrophic and/or ptotic and excision may be considered to improve the neck contour.

Fig. 20.3 Physical exam. The middle figure demonstrates cervical animation to identify platysmal bands.

Anatomy

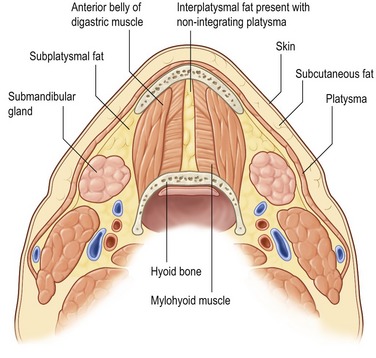

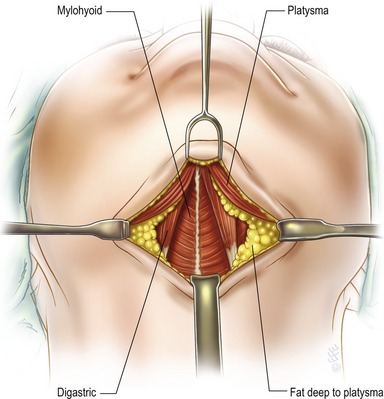

Procedures on the neck are designed to modify the submental/submandibular regions and the cervicomental angle regions by reduction and/or relocation of volume. The excess volume exists in three planes: the superficial plane between the skin and platysma, the intermediate plane comprised of the platysma and interplatysmal fat lying between the bilateral medial platysma edges, and the deep plane beneath the platysma containing the subplatysmal fat, the anterior belly of the digastric muscles, and the submandibular glands.

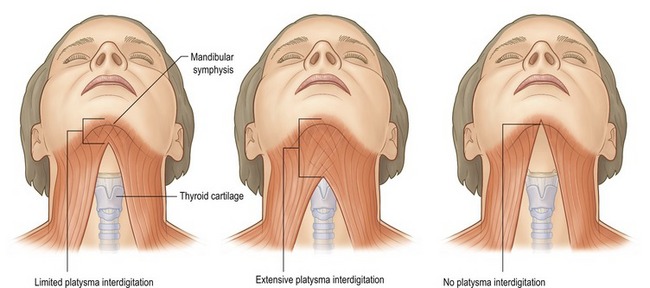

The platysma muscles are thin bilateral structures that extend from the SMAS in the face to the clavicles. There are three variations of platysmal anatomy in the submental region (Fig. 20.5):

• Type I (75%): Interdigitation of the plastysma muscles to a point 1–2 cm posterior to the mandibular symphysis.

• Type II (15%): Interdigitation of the plastysma muscles from the mandibular symphysis to the thyroid cartilage.

In patients with minimal to no plastysmal interdigitation, interplatysmal fat is found in the submental region between the medial edges of the two platysma muscles. This interplatysmal fat is considered a structure of the intermediate plane, but is contiguous with the subplatysmal fat of the deep plane. In those with complete interdigitation (no platysmal decussation) there is no interplatysmal fat and the fat referred to as “subplatysmal fat” is located deep to the plastysma, superficial to, between, and lateral to the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles.

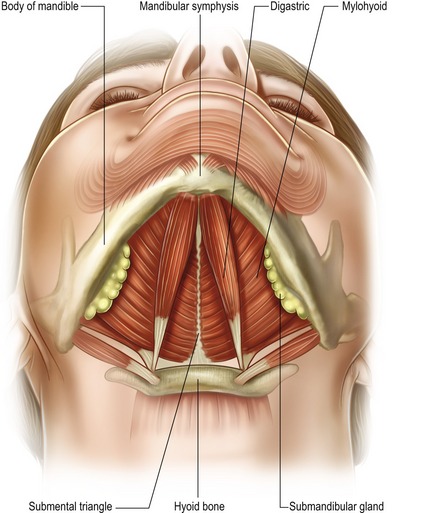

The anterior bellies of the bilateral digastric muscles may be hypertrophied or more visible in some patients resulting in excess submental bulk. These muscles are paired bilateral structures that extend between the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone and the posterior surface of the mandible on either side of the symphysis (Fig. 20.6). Each anterior belly forms one side of the bilateral submandibular triangles. The other two borders of the submandibular triangles are the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the inferior edge of the body of the mandible. These triangles contain the submandibular gland, facial artery and vein, lingual nerve and the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Motor innervation of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle is a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The muscles function as week depressors of the mandible. Excision proceeds without noticeable alteration in function.

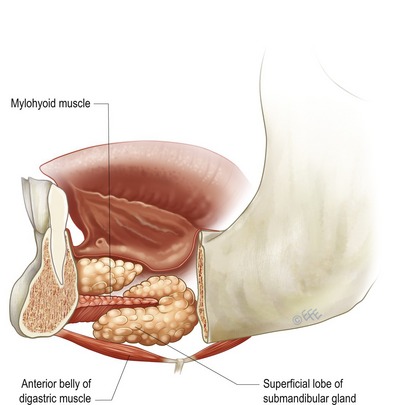

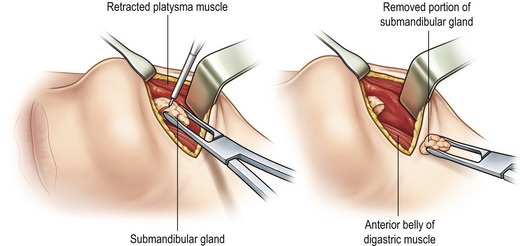

The submandibular gland, a salivary gland, may produce a visible bulge in the region of the submandibular triangle, when it is hypertrophied and/or ptotic (Figs 20.7, 20.8). This bulge disrupts the otherwise planar surface that typifies the smooth contour of a youthful appearing neck. The facial artery and vein run obliquely over the posterior portion of the gland and the marginal mandibular can run horizontally across the superior aspect of the gland in a plane just superficial the facial artery and vein. Both the lingual nerve and the hypoglossal nerve lie deep to the gland. These vascular and neural structures are located in an extracapsular location, thus intracapsular resection of the gland is one strategy to reduce the risk of excessive bleeding and nerve injury.

Technical steps

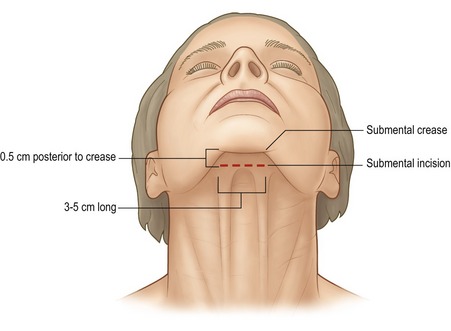

The majority of deep plane procedures are preceded by lipectomy of the superficial neck plane. Subcutaneous infiltration of a local anesthetic containing epinephrine is performed. After the epinephrine-associated vasoconstriction is evident, an incision 3 to 5 cm in length is made parallel to and just posterior to the submental crease (Fig. 20.9). With the aid of a headlight the submental skin flap is raised leaving at least 5 mm of fat deep to the skin. The extent of the dissection is individualized. In most patients the dissection is carried at least to the thyroid cartilage. The mandibular retaining ligaments are released by carrying the dissection anteriorly and laterally. This facilitates the production of a straight and well-defined mandibular border upon skin redraping. One may also consider delaying the final paring of preplatysmal fat in the submandibular region (inferior to the mandibular body) until after SMAS and platysmal tightening as the location of the desired fat for removal may change with relocation of those deeper structures.

Open lipectomy of the superficial plane is performed most effectively when the skin flap is elevated with an even thickness retaining some subcutaneous adipose tissue (5 mm). The fat remaining on the platysma (preplatysmal) and between a decussated platysma (interplatysmal, see Fig. 20.8) is then removed with direct scissors or Bovie dissection, or by suction-assisted lipectomy (SAL). Small (3 mm or less) and single aspiration port cannulas are used, and fat is aspirated from the surface of the platysma, not from the deep surface of the skin.

Access to the subplatysmal (deep) plane is obtained in a medial to lateral approach. In patients with type III platysmal anatomy the medial edges of the platysma are elevated with scissor spreading dissection. In patients with varying degrees of submental platysmal interdigitation (types I and II), a midline incision is made in the platysma with the coagulating current to created two free medial edges. The plastysma is elevated to the level of the thyroid cartilage and laterally far enough to expose the subplatysmal fat, the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles and the submandibular glands (Fig. 20.10). Subplatysmal fat is excised by direct excision or electrocautery. If the anterior bellies of the digastric muscle are to be left unmodified, the interplatysmal and subplatysmal fat is resected only to the caudal surface of the muscles in order to prevent the formation of a submental depression. If a muscle reduction is planed, fat is resected to the projected level of the muscle excision (Fig. 20.11).

Fig. 20.11 Before and after photographs of a patient who has undergone a neck lift with subplatysmal fat reduction

(courtesy of F.N.).

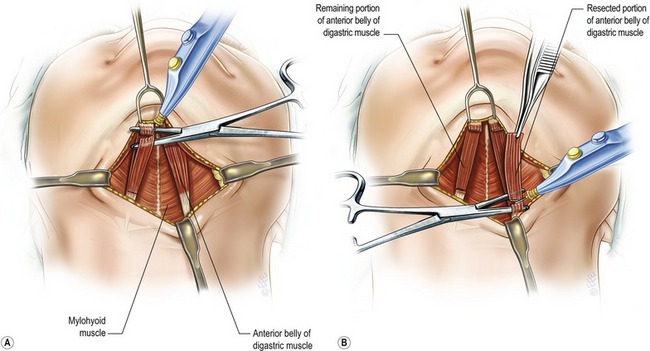

Total or subtotal resection of hypertrophied anterior bellies of the digastric is performed, depending on the preoperative and intraoperative assessment. In a subtotal resection, a hemostat is placed in the non-dominant hand to aid in the determination of the level of the tangential excision (Fig. 20.12). The working end of the hemostat is pierced through the muscle fibers to separate those that are to be removed from those that are to be left in place. Electrocautery is used to transect the muscle fibers just posterior to the mandible and just anterior to the hyoid bone. If a total excision is planned the procedure is similar. The hemostat guides transection of the full thickness of the muscle in the same locations as described for the subtotal excision (Fig. 20.13).

Fig. 20.13 Before and after photographs of a patient who has undergone a neck lift with subtotal resection of the anterior belly of digastric muscle (courtesy of F.N.).

Subsequent to the management of hypertrophied digastric muscles, the submandibular glands are reassessed by direct inspection. Subtotal resection is sometimes indicated to prevent a postoperative bulge. A relatively safe approach to resection is intracapsular with piecemeal removal of the parenchyma (Fig. 20.14). The gland is brought into view with a suture or an Allice clamp. An incision is made in the capsule at the caudal pole of the superficial lobe of the gland to avoid the facial vessels and marginal mandibular nerve associated with the cephalic pole. Following entry into to the intracapular space, electrocautery is used to resect the glandular parenchyma in an incremental fashion. The neck is flexed and re-evaluated with the skin redraped periodically to prevent over-resection (Fig. 20.15).

Fig. 20.15 Before and after photographs of a patient who has undergone a neck lift with intracapsular resection of submandibular gland (courtesy of F.N.).

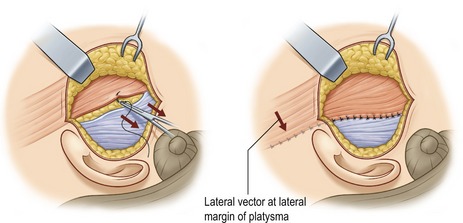

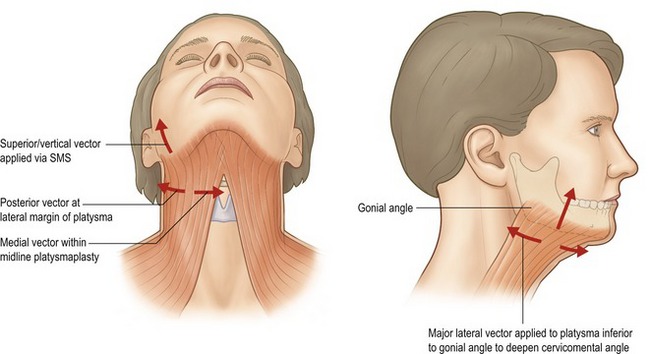

Lateral plastysmaplasty is performed using flap elevation and fixation or plication (Fig. 20.16). The vector and location of the traction force applied is more important than the method employed to generate the force (Fig. 20.17). The force should be applied to the lateral platysma inferior to the gonial angle and oriented in a vector perpendicular to the midline of the neck. The greatest force is applied in the location where the apex of the cervicomental angle is desired, the level of the hypoid bone. This location and vector results in a more acute cervicomental angle and helps further define the outline of the mandible.

Fig. 20.17 Vectors of plastysmal tightening. Arrows demonstrate both vertical and horizontal vectors.

The midline platysmaplasty is performed last. The medial edges of the plastysma muscle are repaired at the midline from the mentum to the inferior edge of the thyroid cartilage. The midline plication is performed with the head positioned so that the cervicofacial angle is 90 degrees or less to reduce tension. Following completion of the midline plication, horizontal myotomy of the medial edges of the platysma is performed for a distance of 3 cm bilaterally at the caudal extent of the plication. The purpose of this muscle transection is two-fold. First, myotomy allows the plastysma composite to shift cephalically under the tension created by the medical repair and lateral repositioning and thus deepens the cervicomental angle. Second, the transection will help reduce the recurrence of platysma bands. The skin is dissected further as is necessary in order to permit sufficient redraping. A closed suction drain is placed and brought out of the surgical plane laterally. The submental incision and postauricular incisions, if present, are closed and a loose, non-binding dressing is applied.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Cervical skin flaps are generally raised preserving some subcutaneous fat (3–5 mm).

• Submandibular gland resection is generally performed in an intracapsular fashion on the superficial lobe in order to minimize the risk of injury to the facial vessels and marginal mandibular nerve.

• Hypertrophy of the anterior belly of the digastic is difficult to assess transcutaneously. Final assessment is performed during the operation.

• In patients with apparent skin excess, retroauricular incisions may not be required. Removal of fat in all three planes as well as digastric and submandibular gland excisions recontour the underlying structures of the neck, so that the apparent skin excess redrapes into the cervicomental angle without requiring skin excision.

• Skin excess usually extends caudal to the thyroid cartilage and posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscles.

Pitfalls

• A common complication in neck recontouring is the over-reduction of volume in the superficial plane in an effort to mask volume problems in the deep plane. This leads to contour irregularities and dynamic tethering of the skin on the underlying plastysma.

• Midline plastysmaplasty should be performed with the chin–neck angle at 90 degrees. If the submental plastysma is repaired at midline with the chin–neck angle more obtuse than 90 degrees, an uncomfortable tight feeling will occur when the patient looks straight ahead or down postoperatively.

• An isolated neck-lift in the presence of significant jowling and decent of the neck–face junction generally will not produce a gratifying result.

• Excessive posterior traction on the neck without adequate elevation vectors anteriorly along the jawline will result in a “hammock” deformity where laxity remains in the submental region and jowls but the lower neck and posterior neck is tightened.

• The most common cause of postoperative submental bulk following neck lift is the presence of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle which may have been unmasked by liposuction.

Summary of steps

1. The majority of deep plane procedures are preceded by lipectomy of the superficial neck plane. Open lipectomy of the superficial plane is performed most effectively when the skin flap is elevated with an even thickness retaining some subcutaneous adipose tissue.

2. Access to the subplatysmal (deep) plane is obtained in a medial to lateral approach. Submandibular gland resection is generally performed in an intracapsular fashion on the superficial lobe in order to minimize the risk of injury to the facial vessels and marginal mandibular nerve.

3. Total or subtotal resection of hypertrophied anterior bellies of the digastric is performed, depending on the preoperative and intraoperative assessment.

4. Electrocautery is used to transect the muscle fibers just posterior the mandible and just anterior to the hyoid bone.

5. Subsequent to the management of hypertrophied digastric muscles, the submandibular glands are reassessed by direct inspection. Subtotal resection is sometimes indicated to prevent a postoperative bulge.

6. Following entry into the intracapsular space, electrocautery is used to resect the glandular parenchyma in an incremental fashion.

7. The goal of plastysma modification is to lessen an obtuse cervicomental angle. This is accomplished by placing the plastysma under tension with forces applied to it both laterally and medially in vectors perpendicular to the long access of its fibers.

8. Many deep plane neck procedures are performed in conjunction with facial rhytidectomies.

9. Lateral plastysmaplasty is performed using flap elevation and fixation.

10. The midline platysmaplasty is performed last. The submental incision and postauricular incisions, if present, are closed and a loose, non-binding dressing is applied.

Aston SJ. Platysma muscle in rhytidoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;3(6):529–539.

Aston SJ. Platysma-SMAS cervicofacial rhytidoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10(3):507–520. Review

Connell BF. Neck contour deformities: the art, engineering, anatomic diagnosis, architectural planning and aesthetic surgical planning. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14(4):683–692.

Connell BF, Marten TJ. Submental crease: elimination of the double chin deformity at rhytidectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;10:10–12.

Connell BF, Shamooun JM. The significance of digastric muscle contouring for rejuvenation of the submental area of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(6):1586–1590.

DeCastro CC. The anatomy of the platysma muscle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(5):680–683.

de Souza Pinto EB. Importance of cervicomental complex treatment in rhytidoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1981;5(1):69–75.

de Pina DP. Diagnosis and technical refinements in rhytidectomy: a personal approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1987;11(1):7–14.

Ellenbogen R, Karlin JV. Visual criteria for success in restoring the youthful neck. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(6):826–837.

Feldman JJ. Corset platysmaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85(3):333–343.

Feldman JJ. Neck lift. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006.

Gradinger GP. Anterior cervicoplasty in the male patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(5):1146–1154.

Guerrerosantos J. Surgical correction of the fatty fallen neck. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;2(5):389–396.

Guyuron F. Problem neck, hyoid bone and submental myotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:830.

Kesserlring UK. Direct approach to the difficult anterior neck region. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1992;16(4):277–282.

Nahai FR, Nahi F. Are sub-platysmal procedures in facial rejuvenation safe and warranted? A review of 100 cases. Presented at The Aesthetic Meeting 2006, Annual Meeting of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons and Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation, Orlando, FL, April 2006.

Owsley JQ, Jr. SMAS-platysma face lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71(4):573–576.

Souther SG, Vistnes LM. Medial approximation of the platysma muscle in the treatment of neck deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;67(5):607–613.

Sullivan PK, Freeman MD, Schmidt S. Contouring the aging neck with submandibular gland suspension. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26(4):465–471.

Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL. The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89(3):441–449.