CHAPTER 177 Dandy-Walker Syndrome

History

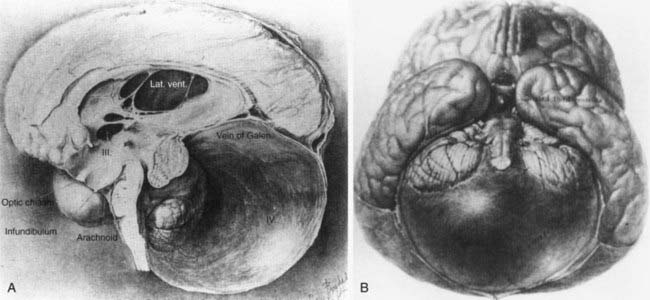

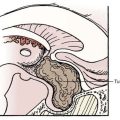

Dandy-Walker syndrome (DWS) represents a congenital malformation characterized by agenesis or hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis, cystic dilation of the fourth ventricle, and enlargement of the posterior fossa with or without hydrocephalus. The first autopsy description of such a clinical picture appeared in 1887 by Sutton.1 It was not until 1914 that Dandy and Blackfan realized an association between hydrocephalus and cystic fourth ventricular dilation in a 13-month old girl.2 The malformation was further characterized by Dandy3 in 1921 and by Taggart and Walker4 in 1942 as being related to congenital atresia of the fourth ventricular exit foramina (Fig. 177-1). However, it was Benda in an autopsy series in 1954 who first used the term Dandy-Walker syndrome to describe this condition and offer a new theory on its etiology.5 He postulated that failure of normal regressive changes in the posterior medullary velum and absence of the cerebellar vermis formed a cyst from the distal end of the fourth ventricle that separated the cerebellar hemispheres. Since that time, no significant progress has been made in terms of etiology; however, DWS is a well-known malformation that has been associated with other central nervous system (CNS) and systemic anomalies, including genetic aberrations, environmental factors, teratogens, and congenital infections to name a few.6 Advances in diagnostic imaging and increased accessibility to them may have led to the overdiagnosis of DWS.7–9 This chapter aims to describe the basic clinicopathologic features of DWS; its diagnosis with other CNS, systemic, and genetic associations; and treatment controversies that still exist today.

Embryology, Pathophysiology, and Etiology

Cerebellar development begins in the ninth week of gestation when the genesis of the cerebellar hemispheres occurs from the rhombic lips. Subsequently, the hemispheres fuse to form the vermis. The choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle and the foramina of Magendie form around the 10th week of gestation from the rhombic vesicle. The fourth ventricle develops when cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) accumulates within its space. The cerebellar lobules develop from an anterior to posterior direction and are completely formed by week 18.10 The cerebellum develops slower than the cerebral hemispheres and therefore appears smaller at 20 weeks of gestation relative to the large posterior fossa CSF spaces, leading to a potential overdiagnosis of vermian hypoplasia by antenatal ultrasound.

Terminology and Differential Diagnosis

Dandy-Walker variant (DWV) is a term that was first introduced by Harwood-Nash and Fitz to describe a milder spectrum of DWS-like signs that were not congruent with the classic definition. It consists of an inferior cerebellar vermian defect and communication between normal-sized cisterna magna and the fourth ventricle.11 Dandy-Walker complex (DWC) is another term coined to describe a continuum of posterior fossa anomalies categorized from mild (mega-cisterna magna only) to moderate (mild hypoplasia of vermis, enlarged fourth ventricle) to severe (agenesis of vermis, dilation of posterior fossa cyst and fourth ventricle).12

This wide spectrum of posterior fossa cystic malformations provides the basis for a differential diagnosis in prenatal or postnatal presentations. These include DWV, mega-cisterna magna, posterior fossa arachnoid cyst, persistent Blake pouch cyst, fourth ventriculocele, and congenital vermian hypoplasia.12–14

Clinical Features

DWS has been reported to occur in 1 of 25,000 to 30,000 newborns15 with the highest incidence in infants younger than 1 year.16,17 However, diagnosis may be delayed until adolescence or even adulthood. Concurrent hydrocephalus may not be present on prenatal imaging or at birth but has been reported to occur in as few as 2% and as many as 90% of all patients.18–21 The higher end of this wide range is probably secondary to historical series of patients with hydrocephalus being the selected subgroup presenting to neurosurgical services. Those who develop hydrocephalus usually do so by 3 months of age.15 In one retrospective study of 72 children, 50% presented before 1 year of age, with a distribution up to 18 years of age, whereas the oldest reported newly diagnosed patient with DWS was 75 years old.22 The most common postnatal presentation is macrocrania. Other signs and symptoms may include sunset sign, large posterior fossa, seizures, spasticity, lethargy, delayed milestones, respiratory failure, apnea, increased intracranial pressure, and hydrocephalus. Older children may present similarly to patients with posterior fossa tumors, and symptoms may include nystagmus and ataxia.23 Numerous malformations are described in the literature in association with DWS and its variants. The incidence of associated anomalies in the CNS is variable but has been reported as high as 68%, with systemic abnormalities present in about one fourth of patients.24 The most commonly associated CNS abnormality is agenesis of corpus callosum, whereas systemically, capillary hemangiomas and cardiac defects represent the most frequent associations (Table 177-1).25

TABLE 177-1 Central Nervous System and Systemic Anomalies Associated with Dandy-Walker Syndrome

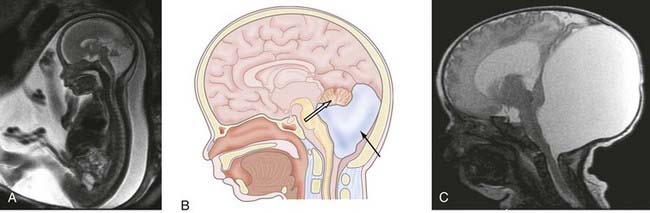

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM |

Historically, the only imaging characteristic consistent with DWS was an elevated torcular Herophili visible on plain radiograph.26 It was known as Bucy’s sign. Presently, diagnosis of DWS is made based on anatomic findings that may be identified on fetal or postnatal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 177-2). When evaluating prenatal imaging, some authors have cautioned about limitations of ultrasound diagnosis being discordant to postnatal diagnosis or postmortem pathologic findings.9,27,28 Fetal MRI has been used as a helpful adjunct in diagnosing this condition prenatally given the potential for associated congenital abnormalities and incidence of cognitive and developmental delays. As some parents may elect to terminate pregnancies based on DWS diagnosis, it is important that an accurate prenatal diagnosis be reached with advanced MRI based on CNS and systemic associated abnormalities and a cytogenic evaluation. Chromosomal aberrations occur in about 50% of cases. Trisomy 13 and 18 and triploidy are the most commonly reported abnormalities.8,29 Inheritance patterns may be X-linked or autosomal recessive as reported in familial occurrences. If DWS is associated with a single gene disorder, recurrence risk may be high for subsequent pregnancies. In the absence of such findings, the risk for recurrence is 1% to 5%.29 When present, genetic mutations are associated with non-CNS systemic abnormalities in most patients.15 The future advancement of genetic definitions of developmental disorders may allow for DWS to be separated into specific subentities described in terms of molecular abnormalities.

Treatment

Treatment of DWS has historically been related to the etiologic theory of that particular time. In the early series, based on the belief that hydrocephalus in DWS was due to obstruction of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie, surgical treatment involved excision of the posterior fossa membranes to facilitate spinal fluid flow.3 Although there were reports of patient survival with this procedure, its poor efficacy was subsequently demonstrated in multiple series in which up to 75% of patients with membrane resections required a shunt.4,16,30 This brought about subsequent attempts of various shunting techniques, initially with concurrent resection of posterior fossa membranes and later without. Presently, although largely abandoned as a procedure, resection or fenestration of obstructing membranes may still play a role in the treatment of DWS, particularly in older children.31

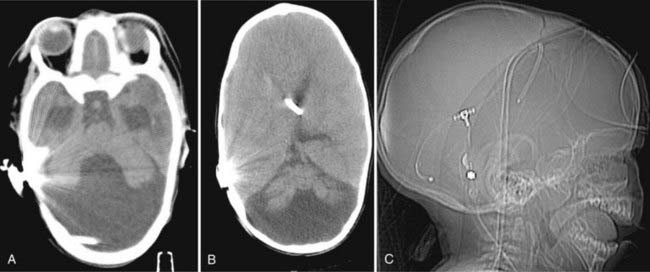

Currently, diversion of CSF through shunting is the universally accepted standard treatment of DWS (Fig. 177-3). However, significant controversy exists in terms of which shunting procedure yields the best results. Options include (1) shunting the supratentorial compartment, (2) shunting the cerebellar cyst, or (3) shunting both compartments (dual shunt). Sawaya and colleagues16 and Hirsch and coworkers,17 in their respective studies, suggested that shunting the cyst alone may be the primary treatment of choice. A greater proportion of their patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) subsequently required cyst drainage than those for whom a cystoperitoneal shunt (CPS) was the initial procedure. Asai and colleagues suggested that the success of CPS depends on the initial patency of the aqueduct and therefore that identification of aqueductal stenosis may determine which procedure should be performed first.32 Bindal and coworkers found no statistical difference between shunting the cyst and the ventricle and thus recommended VPS to be the initial procedure of choice given its lower rate of morbidity.33 The authors also found that irrespective of the initial choice of shunt, 38% of patients subsequently required shunting of the second compartment. VPS may be easier to place and has a relatively lower incidence of migration or malposition. Further, VPS can provide early decompression of ventriculomegaly to potentially allow for a satisfactory cognitive development. As a result, other authors have also advocated this approach.30 However, upward herniation with hypothalamic dysfunction and functional aqueductal stenosis resulting in an isolated fourth ventricle has been reported with supratentorial shunting.34,35 Osenbach and Menezes’ series achieved a 92% success rate with “dual” shunting of the posterior fossa cyst and lateral ventricle.18 Although pressures across the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments are equalized, such a setup may also result in significantly decreased flow across the aqueduct, thus causing stenosis.

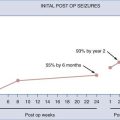

Mohanty and colleagues reviewed changing trends in the treatment protocols of DWS in a single institution between 1986 and 2002 because they progressed from cystectomy through various shunting procedures to endoscopic fenestrations.21 Radiographically, VPS placement achieved ventricular size reduction in 88% of patients compared with 38% of those with CPS. On the other hand, cyst size was significantly reduced in 88% of patients with CPS and in 62% of those with VPS. They reported no significant difference in intellectual outcome between different treatments. Endoscopic procedures achieved a slight reduction in ventricular size in all patients with a varying degree of cyst size reduction.21 The authors reported endoscopic interventions in 21 patients. Procedures may consist of (1) endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV), (2) aqueductal “stent” with shunting, and (3) endoscope-assisted transtentorial proximal catheter placement with shunting. ETV alone was performed in 16 patients when the aqueduct was noted to be patent. Aqueductal stents or fenestrations were combined with ETV in patients with aqueductal stenosis (five patients). The authors described a 24% endoscopic procedure failure, which is in accordance with the failure rate of ETV in the treatment of obstructive hydrocephalus. They argued that, based on their experience, a generous residual ventriculomegaly may prevent secondary aqueductal stenosis and that an endoscopic procedure may an acceptable primary intervention for DWS. These newer approaches do not necessarily require placement of a traditional shunt or may be used in combination with it. Given the relative small number of patients treated and variable success rates, however, it is difficult to assess efficacy over other surgical options.

Based on current retrospective evidence, it would be difficult to establish a universal treatment algorithm for DWS. Any such algorithm would be designed for the individual patient based on symptoms and age. The present trend is to start with the safest and most effective treatment, which is usually a VPS for an infant with progressive hydrocephalus. The cyst is usually treated secondarily with fenestration or shunting; excision of posterior fossa membranes should be viewed far down the list.17 Presently, there appears to be a trend amongst neurosurgeons to initially place a shunt (CPS or VPS) without excision of posterior fossa membranes.36 The initial system may be converted to a dual system in cases of failure. With the presence of aqueductal stenosis, a combined procedure of ETV and aqueductal stenting (used in extreme cases that have been refractory to other forms of treatment like shunting and endoscopic or open fenestration)37 or a dual shunt may be yet another option. Additionally, there are certain other unique situations that may warrant a more individualized approach to treatment. The presence of an occipital meningocele would be one such example. Irrespective of treatment options, the primary goal is uniform, that is, functional patient survival without procedural complications. Additionally, with the development of advanced surgical, medical, and imaging techniques, the emphasis on outcome measures has shifted from patients’ survival to functional and cognitive outcomes, making it difficult to directly compare studies using different surgical approaches to treat DWS.38

Prognosis

Patients with DWS have variable prognosis. This is not only due to the spectrum of severity of DWS but also to the associated conditions. The mortality rate has clearly improved since the early days when the condition was recognized. The mortality rate was 100% in 1942 and has decreased to about 10% with treatment in more recent studies.4,17,32,33 This improvement is likely due to advances in medical and surgical care and a more adequate treatment of hydrocephalus. Presently, death usually occurs secondary to shunt malfunction or shunt-associated morbidity and associated systemic anomalies. Despite this improvement, mortality rates may be quite variable when considering antenatal diagnosis of DWS. Antenatal sonographic studies diagnosing DWS or DWV confirm a high incidence of associated anomalies with only about 6% to 20% of fetuses surviving to birth.12,39 Antenatal diagnostic techniques, mainly ultrasound and MRI, in combination with genetic characterization of DWS, may allow for better prognostication of this condition in the future.

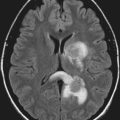

In children who have successfully been treated for hydrocephalus, the prognosis is dependent on associated conditions. Seizures, hearing or visual problems, and other systemic or CNS abnormalities are predictive of worse outcome.33 In the absence of other abnormalities, some authors report intelligent quotients (IQa) of 80 or more in 50% of long-term survivors and normal IQs in 30%.33,40,41 More recently, Boddaert and associates found 14 patients with normal IQs who had normal vermian lobulation without supratentorial anomalies as demonstrated by MRI.38 This is in contrast to the remaining developmentally delayed DWS patients with abnormalities in their vermis or the supratentorial compartment.38 The authors concluded that vermian lobulation may be a useful prognostic factor especially when applied to antenatal MRI.

Asai A, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Humphreys RP. Dandy-Walker syndrome: experience at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Pediatr Neurosci. 1989;15:66-73.

Benda CE. The Dandy-Walker syndrome or the so-called atresia of the foramen Magendie. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1954;1:14-29.

Bindal AK, Storrs BB, McLone DG. Management of the Dandy-Walker syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1990-1991;16:163-169.

Boddaert N, Klein O, Ferguson N, et al. Intellectual prognosis of the Dandy-Walker malformation in children: the importance of vermian lobulation. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:320-324.

Dandy WE. The diagnosis and treatment of hydrocephalus due to occlusions of the foramina of Magendie and Luschka. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1921;32:113-124.

Dandy WE, Blackfan KD. Internal hydrocephalus. An experimental, clinical and patholological study. Am J Dis Child. 1914;8:406-482.

Klein O, Pierre-Kahn A, Boddaert N, et al. Dandy-Walker malformation: prenatal diagnosis and prognosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19:484-489.

Mohanty A, Biswas A, Satish S, et al. Treatment options for Dandy-Walker malformation. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:348-356.

Naidich TP, Radkowski MA, McLone DG, Leestma J. Chronic cerebral herniation in shunted Dandy-Walker malformation. Radiology. 1986;158:431-434.

Osenbach RK, Menezes AH. Diagnosis and management of the Dandy-Walker malformation: 30 years of experience. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:179-189.

Raimondi AJ, Samuelson G, Yarzagaray L, Norton T. Atresia of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie: the Dandy-Walker cyst. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:202-216.

Sawaya R, McLaurin RL. Dandy-Walker syndrome. Clinical analysis of 23 cases. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:89-98.

Shurtleff DB, Kronmal R, Foltz EL. Follow-up comparison of hydrocephalus with and without myelomeningocele. J Neurosurg. 1975;42:61-68.

Sutton JB. The lateral recesses of the fourth ventricle: their relation to certain cysts and tumors of the cerebellum, and to occipital meningocele. Brain. 1887;9:352-361.

Taggart JR, Walker AE. Congenital atresia of the foramens of Luschka and Magendie. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1942;43:583-612.

1 Sutton JB. The lateral recesses of the fourth ventricle: their relation to certain cysts and tumors of the cerebellum, and to occipital meningocele. Brain. 1887;9:352-361.

2 Dandy WE, Blackfan KD. Internal hydrocephalus. An experimental, clinical and pathological study. Am J Dis Child. 1914;8:406-482.

3 Dandy WE. The diagnosis and treatment of hydrocephalus due to occlusions of the foramina of Magendie and Luschka. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1921;32:113-124.

4 Taggart JR, Walker AE. Congenital atresia of the foramens of Luschka and Magendie. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1942;43:583-612.

5 Benda CE. The Dandy-Walker syndrome or the so-called atresia of the foramen Magendie. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1954;1:14-29.

6 Murray JC, Johnson JA, Bird TD. Dandy-Walker malformation: etiologic heterogeneity and empiric recurrence risks. Clin Genet. 1985;28:272-283.

7 Adamsbaum C, Moutard ML, André C, et al. MRI of the fetal posterior fossa. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:124-140.

8 Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT. Magnetic resonance evaluation of fetal ventriculomegaly-associated congenital malformations and lesions. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;10:429-443.

9 Phillips JJ, Mahony BS, Siebert JR, et al. Dandy-Walker malformation complex: correlation between ultrasonographic diagnosis and postmortem neuropathology. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:685-693.

10 Bromley B, Nadel AS, Pauker S, et al. Closure of the cerebellar vermis: evaluation with second trimester US. Radiol. 1994;193:761-763.

11 Harwood-Nash DC, Fitz CR. Neuroradiology in Infants and Children. St. Louis: Mosby, 1976.

12 Harper T, Fordham LA, Wolfe HM. The fetal Dandy Walker complex: associated anomalies, perinatal outcome and postnatal imaging. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:277-281.

13 Utsunomiya H, Yamashita S, Takano K, et al. Midline cystic malformations of the brain: imaging diagnosis and classification based on embryologic analysis. Radiat Med. 2006;24:471-481.

14 ten Donkelaar HJ, Lammens M, Wesseling P, et al. Development and developmental disorders of the human cerebellum. J Neurol. 2003;250:1025-1036.

15 Russ PD, Pretorius DH, Johnson MJ. Dandy-Walker syndrome: a review of fifteen cases evaluated by prenatal sonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:401-406.

16 Sawaya R, McLaurin RL. Dandy-Walker syndrome. Clinical analysis of 23 cases. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:89-98.

17 Hirsch JF, Pierre-Kahn A, Renier D, et al. The Dandy-Walker malformation. A review of 40 cases. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:515-522.

18 Osenbach RK, Menezes AH. Diagnosis and management of the Dandy-Walker malformation: 30 years of experience. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:179-189.

19 James HE, Kaiser G, Schut L, Bruce DA. Problems of diagnosis and treatment in the Dandy-Walker syndrome. Childs Brain. 1979;5:24-30.

20 Shurtleff DB, Kronmal R, Foltz EL. Follow-up comparison of hydrocephalus with and without myelomeningocele. J Neurosurg. 1975;42:61-68.

21 Mohanty A, Biswas A, Satish S, et al. Treatment options for Dandy-Walker malformation. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:348-356.

22 Freeman SR, Jones PH. Old age presentation of the Dandy-Walker syndrome associated with unilateral sudden sensorineural deafness and vertigo. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:127-131. 2002

23 Fischer EG. Dandy-Walker syndrome: an evaluation of surgical treatment. J Neurosurg. 1973;39:615-621.

24 Hart MN, Malamud N, Ellis WG. The Dandy-Walker syndrome. A clinicopathological study based on 28 cases. Neurology. 1972;22:771-780.

25 Olson GS, Halpe DC, Kaplan AM, Spataro J. Dandy-Walker malformation and associated cardiac anomalies. Childs Brain. 1981;8:173-180.

26 Bucy PC. Hydrocephalus. In: Brennemann J, editor. Practice of Pediatrics. Hagerstown, MD: W. F. Prior Company; 1939:1-28.

27 Laing FC, Frates MC, Brown DL, et al. Sonography of the fetal posterior fossa: false appearance of mega-cisterna magna and Dandy-Walker variant. Radiology. 1994;192:247-251.

28 Carroll SG, Porter H, Abdel-Fattah S, et al. Correlation of prenatal ultrasound diagnosis and pathologic findings in fetal brain abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:149-153.

29 Lin YH, Chen CP, Chen TC, et al. Familial occurrence of isolated Dandy-Walker variant in two consecutive male fetuses. Genet Couns. 2006;17:461-463.

30 Carmel PW, Antunes JL, Hilal SK, Gold AP. Dandy-Walker syndrome: clinico-pathological features and re-evaluation of modes of treatment. Surg Neurol. 1977;8:132-138.

31 Almeida GM, Matushita H, Mattosinho-França LC, Shibata MK. Dandy-Walker syndrome: posterior fossa craniectomy and cyst fenestration after several shunt revisions. Childs Nerv Syst. 1990;6:335-337.

32 Asai A, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Humphreys RP. Dandy-Walker syndrome: experience at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Pediatr Neurosci. 1989;15:66-73.

33 Bindal AK, Storrs BB, McLone DG. Management of the Dandy-Walker syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1990-1991;16:163-169.

34 Raimondi AJ, Samuelson G, Yarzagaray L, Norton T. Atresia of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie: the Dandy-Walker cyst. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:202-216.

35 Naidich TP, Radkowski MA, McLone DG, Leestma J. Chronic cerebral herniation in shunted Dandy-Walker malformation. Radiology. 1986;158:431-434.

36 Gerszten PC, Albright AL. Relationship between cerebellar appearance and function in children with Dandy-Walker syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1995;23:86-92.

37 Fritsch MJ, Kienke S, Manwaring KH, et al. Endoscopic aqueductoplasty and interventriculostomy for the treatment of isolated fourth ventricle in children. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:372-377.

38 Boddaert N, Klein O, Ferguson N, et al. Intellectual prognosis of the Dandy-Walker malformation in children: the importance of vermian lobulation. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:320-324.

39 Forzano F, Mansour S, Ierullo A, et al. Posterior fossa malformation in fetuses: a report of 56 further cases and a review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:495-501.

40 Klein O, Pierre-Kahn A, Boddaert N, et al. Dandy-Walker malformation: prenatal diagnosis and prognosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19:484-489.

41 Maria BL, Zinreich SJ, Carson BC, et al. Dandy-Walker syndrome revisited. Pediatr Neurosci. 1987;13:45-51.