41 Cystic Fibrosis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

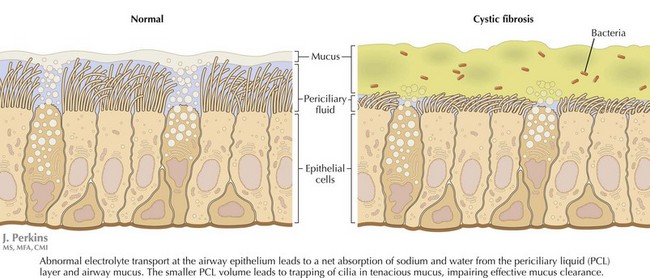

CF is caused by defects in a single gene on the long arm of chromosome 7, which codes for the CFTR. The protein is a cyclic adenosine monophosphate regulated chloride channel. More than 1400 mutations in the CFTR gene have been described to date. Defective CFTR function leads to abnormal electrolyte transport at epithelial surfaces, resulting in the net reabsorption of water and dehydration of luminal secretions (Figure 41-1). Accumulation of these viscid secretions results in obstruction, inflammation, tissue damage, and progressive scarring in a number of organs. Despite the discovery of the gene for CF in 1989, much of the pathogenesis of this complicated condition remains to be understood. The disease is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, with an annual incidence in the United States of approximately one in 3,500 live births. There is a significantly higher carrier frequency in whites compared with other groups.

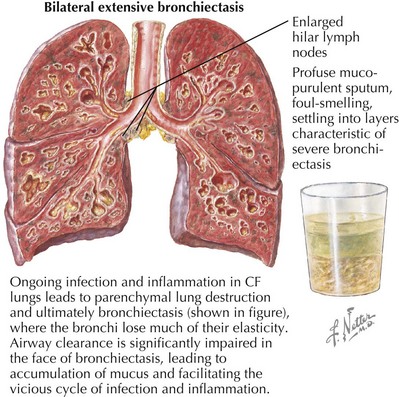

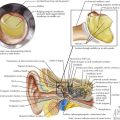

The bulk of morbidity and mortality associated with CF is related to lung disease. Here, excessive sodium and water resorption from the airway surface leads to dehydrated mucus that is hard to clear effectively. Impaired airway clearance and defects in airway innate defense facilitate chronic bacterial colonization and intermittent acute infection. CF lung disease is thus characterized by a self-perpetuating cycle of airway obstruction, chronic bacterial infection, and airway inflammation. Ultimately, inflammatory destruction of lung tissue results in progressive bronchiectasis, further impairing airway clearance and facilitating this chronic cycle of infection and inflammation (Figure 41-2). A similar cycle of chronic inflammation and infection occurs in the paranasal sinuses of patients with CF causing chronic pansinusitis. Nasal polyps are found commonly in patients with CF and can compound chronic sinusitis.

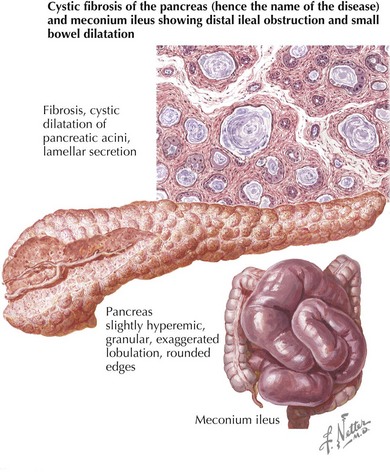

In the GI system, obstruction of pancreatic ducts with viscid secretions results in exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and intestinal malabsorption in 90% of patients. Pancreatic endocrine function can also be impaired resulting in diabetes. CF-related diabetes (CFRD), which is distinct from both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, rarely occurs in the first decade, but its incidence increases after that with age. Accumulation of viscid secretions can also cause small bowel obstruction, particularly in newborns, a condition known as meconium ileus (Figure 41-3). Bowel obstruction can also occur in older children and adults as a result of mucus impaction in the distal small bowel, a condition known as distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS) . The liver is also commonly affected in patients with CF. A number of different types of liver disease can be seen, including asymptomatic elevation of liver enzymes, hepatic steatosis, and microgallbladder; however, the most prominent finding is focal biliary cirrhosis. This is likely caused by bile duct obstruction, and disease can progress to widespread cirrhosis with portal hypertension and liver failure in some patients. Other GI problems can occur in CF, including gastroesophageal reflux (GER), which is common in both children and adults, chronic pancreatitis, and rectal prolapse.

Clinical Presentation

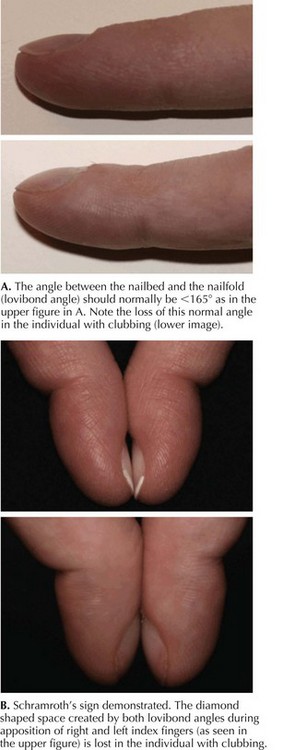

Pulmonary involvement in CF most often presents with recurrent respiratory infections, which, in infants and small children, may be accompanied by wheeze. Respiratory symptoms in younger children can be hard to differentiate from those of recurrent viral illnesses or asthma. Patients can have a chronic cough, which is usually productive. Sputum, if it is expectorated, can be yellow or green. Chest examination can reveal hyperinflation, wheezing from lower airway obstruction, or crackles caused by peripheral airspace disease. Children with CF often have digital clubbing, although this can be hard to appreciate in infants (Figure 41-4). Sinus disease can present as chronic nasal congestion or facial pain, and examination may reveal nasal polyps and sinus tenderness.

Amin R, Ratjen F. Cystic fibrosis: a review of pulmonary and nutritional therapies. Adv Pediatr. 2008;55:99-121.

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: 2007 Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD.

The Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/home.html

Flume PA, O’Sullivan BP, Robinson KA, et al. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(10):957-969.

Flume PA, Robinson KA, O’Sullivan BP, The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: airway clearance therapies. Respir Care. 2009;54(4):522-537.