Chapter 12 CYANOSIS

Causes of Cyanosis

• Double-outlet right ventricle

• Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

• Left-to-right shunt with pulmonary edema

• Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR)

• Aspiration (meconium, blood, amniotic fluid, mucus, or milk)

• Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM)

• Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH)

• Hyaline membrane disease (HMD)

• Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN)

Key Historical Features

Onset at birth may result from transient tachypnea of the necoborn (TTN), respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, meconium aspiration syndrome, CDH, or CCAM

Onset at birth may result from transient tachypnea of the necoborn (TTN), respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, meconium aspiration syndrome, CDH, or CCAM

Onset several hours after birth may be related to cyanotic congenital heart disease, postnatal aspiration syndromes, or TEF

Onset several hours after birth may be related to cyanotic congenital heart disease, postnatal aspiration syndromes, or TEF

Maternal diabetes increases the risk of TTN, HMD, and hypoglycemia

Maternal diabetes increases the risk of TTN, HMD, and hypoglycemia

Narcotic use may lead to narcotic withdrawal, often 36 to 48 hours after birth

Narcotic use may lead to narcotic withdrawal, often 36 to 48 hours after birth

Pregnancy-induced hypertension increases risk of polycythemia and hypoglycemia

Pregnancy-induced hypertension increases risk of polycythemia and hypoglycemia

Prolonged rupture of membranes increases the risk of sepsis and pneumonia

Prolonged rupture of membranes increases the risk of sepsis and pneumonia

Intrapartum fever increases the risk of infection in the newborn

Intrapartum fever increases the risk of infection in the newborn

Narcotic analgesia or anesthesia increases the risk of newborn cyanosis

Narcotic analgesia or anesthesia increases the risk of newborn cyanosis

Nonreassuring fetal heart-rate tracings and perinatal hypoxic depression at birth increase the risk of hypotension, metabolic acidosis, and cerebral edema in the newborn

Nonreassuring fetal heart-rate tracings and perinatal hypoxic depression at birth increase the risk of hypotension, metabolic acidosis, and cerebral edema in the newborn

Cesarean section deliveries without labor are associated with a higher risk of TTN and persistent pulmonary hypertension

Cesarean section deliveries without labor are associated with a higher risk of TTN and persistent pulmonary hypertension

Difficult vaginal delivery may cause an Erb palsy with associated phrenic nerve paralysis, leading to respiratory distress

Difficult vaginal delivery may cause an Erb palsy with associated phrenic nerve paralysis, leading to respiratory distress

Prenatal History That May Increase Risk of Polycythemia and Hypoglycemia

Oligohydramnios may lead to pulmonary hypoplasia

Oligohydramnios may lead to pulmonary hypoplasia

Polyhydramnios may be associated with TEF, neurologic conditions, or anatomic abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract

Polyhydramnios may be associated with TEF, neurologic conditions, or anatomic abnormalities of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract

A sibling with a history of early onset invasive group B streptococcal (GBS) disease confers a higher risk of early onset GBS infection

A sibling with a history of early onset invasive group B streptococcal (GBS) disease confers a higher risk of early onset GBS infection

A family history of congenital heart disease increases the risk of recurrence

A family history of congenital heart disease increases the risk of recurrence

A sibling with a history of surfactant protein B deficiency increases the risk of recurrence

A sibling with a history of surfactant protein B deficiency increases the risk of recurrence

Key Physical Findings

Blood pressure measurement in all four extremities

Blood pressure measurement in all four extremities

Determination of whether cyanosis is peripheral or central

Determination of whether cyanosis is peripheral or central

Head and neck examination for nasal flaring: holding the bell of the stethoscope over the nostrils may help identify nasal obstruction from choanal atresia

Head and neck examination for nasal flaring: holding the bell of the stethoscope over the nostrils may help identify nasal obstruction from choanal atresia

Cardiac examination for heart rate, heart sounds, and murmurs; location of the apical impulse and presence of a precordial thrill

Cardiac examination for heart rate, heart sounds, and murmurs; location of the apical impulse and presence of a precordial thrill

Evaluation of respirations for respiratory rate, retractions, and grunting

Evaluation of respirations for respiratory rate, retractions, and grunting

Evaluation of the shape of the chest

Evaluation of the shape of the chest

Pulmonary examination for equal air entry bilaterally, presence of breath sounds in all lung fields, rales, and rhonchi

Pulmonary examination for equal air entry bilaterally, presence of breath sounds in all lung fields, rales, and rhonchi

Abdominal examination for distension, hepatosplenomegaly, and bowel sounds

Abdominal examination for distension, hepatosplenomegaly, and bowel sounds

Assessment of perfusion by capillary refill time

Assessment of perfusion by capillary refill time

Palpation of both brachial and femoral pulses with assessment of the quality and volume of the pulses

Palpation of both brachial and femoral pulses with assessment of the quality and volume of the pulses

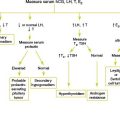

Suggested Work-up

| Pulse oximetry monitoring | If there is severe cyanosis with respiratory distress, the pulse oximeter should be placed over the right hand and a lower extremity to detect the gradient across the ductus arteriosus |

| Hyperoxia test | Indicated if the infant’s pulse oximeter reading is less than 85% on both room air and 100% oxygen |

| An arterial blood gas (ABG) is obtained on room air, the infant is placed on 100% oxygen for 10 to 15 minutes, then the ABG is repeated. If the cause of cyanosis is pulmonary, the Pao2 should increase by 30 mm Hg. If the cause is cardiac, there should be minimal improvement in the PaO2. The initial ABG should be obtained with co-oximetry because methemoglobinemia can also cause cyanosis | |

| Chest radiograph | To determine the locations of the stomach, liver, and heart to evaluate for dextrocardia and situs inversus. To evaluate the size and shape of the heart; pulmonary vascular markings, lung volumes, and interstitial markings; pneumothorax, pleural effusion, infiltrates, or elevated hemidiaphragms. To evaluate the bony thoracic cage and to look for fractures of the ribs, humerus, or clavicles |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) | To evaluate for arrhythmias |

| Echocardiogram | To evaluate for congenital cardiac lesions and pulmonary hypertension |

| CBC with differential count | To evaluate for polycythemia, anemia, neutropenia, leukopenia, abnormal immature-to-total neutrophil ratio, and thrombocytopenia |

| Blood culture | If sepsis is suspected |

| Spinal tap | If sepsis is suspected |

Additional Work-up

| Serum electrolytes | To evaluate for electrolyte abnormalities contributing to heart block if the infant’s heart rate does not increase appropriately with stimulation |

| Serum calcium and magnesium | Should be obtained in newborns in whom other causes are ruled out |

| Ultrasound | To evaluate for pleural effusion or paradoxical motion of the diaphragm |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest | May be helpful if the diagnosis is not clear and in detecting congenital abnormalities and tumors of the mediastinum, lungs, and heart |

| Upper GI contrast study | To evaluate for severe gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis when cyanosis occurs with feeding |

| Metabolic screening of urine and drug screening of urine and meconium | If clinically indicated |

1. Brousseau T., Sharieff G.Q. Newborn emergencies: the first 30 days of life. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:69–84.

2. Fuloria M., Kreiter S. The newborn examination: part I. Emergencies and common abnormalities involving the skin, head, neck, chest, and respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:61–68.

3. Hashim M.J., Guillet R. Common issues in the care of sick neonates. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1685–1692.

4. Sasidharan P. An approach to diagnosis and management of cyanosis and tachypnea in term infants. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;51:999–1021.