Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease

1. How often do patients with diabetes mellitus demonstrate an associated skin disorder?

Most published studies report that 30% to 50% of patients with diabetes mellitus ultimately develop a skin disorder attributable to their primary disease. However, if one includes subtle findings such as nail changes, vascular changes, and alteration of the cutaneous connective tissue, the incidence approaches 100%. Skin disorders most often manifest in patients with known diabetes mellitus, but cutaneous manifestations also may be an early sign of undiagnosed diabetes.

2. Are any skin disorders pathognomonic of diabetes mellitus?

Yes. Bullous diabeticorum (bullous eruption of diabetes, diabetic bullae) is specific for diabetes mellitus, but it is uncommon. Bullous diabeticorum most often occurs in patients with severe diabetes, particularly those with associated peripheral neuropathy. In general, all other reported skin findings may be found to some extent in normal individuals. However, some cutaneous conditions (e.g., necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum) demonstrate strong associations with diabetes.

3. What is bullous diabeticorum?

Bullous diabeticorum is a blistering disorder that primarily occurs on the distal extremities of diabetic patients. Lesions typically appear as spontaneous tense blisters that are asymptomatic, except for a burning sensation. The exact mechanism is not understood, but most patients have peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, or nephropathy.

4. What are the skin disorders most likely to be encountered in diabetic patients?

The most common skin disorders are finger pebbles, nail bed telangiectasia, red face (rubeosis), skin tags (acrochordons), diabetic dermopathy, yellow skin, yellow nails, and pedal petechial purpura (Table 55-1). Less common cutaneous disorders that are closely associated with diabetes mellitus include necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, bullous eruption of diabetes, acanthosis nigricans, and scleredema adultorum.

TABLE 55-1.

COMMON CUTANEOUS FINDINGS IN DIABETES MELLITUS

| CUTANEOUS FINDING | INCIDENCE IN CONTROLS (%) | INCIDENCE IN DIABETIC PATIENTS (%) |

| Finger pebbles | 21 | 75 |

| Nail bed telangiectasia | 12 | 65 |

| Rubeosis (red face) | 18 | 59 |

| Skin tags | 3 | 55 |

| Diabetic dermopathy | Uncommon | 54 |

| Yellow skin | 24 | 51 |

| Yellow nails | Uncommon | 50 |

| Erythrasma | Uncommon | 47 |

| Diabetic thick skin | Uncommon | 30 |

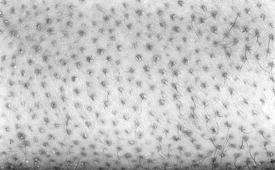

Finger pebbles (Huntley’s papules) are multiple, grouped minute papules that tend to affect the extensor surfaces of the fingers, particularly near the knuckles. They are asymptomatic and may be extremely subtle in appearance. Histologically, finger pebbles are the result of increased collagen in the dermal papillae. The pathogenesis is not understood.

6. What is acanthosis nigricans?

Acanthosis nigricans is a skin condition caused by papillomatous (wartlike) hyperplasia of the skin. It is associated with various conditions, including diabetes mellitus, obesity, acromegaly, Cushing’s syndrome, certain medications, and underlying malignant diseases. Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin-dependent diabetes has been linked to insulin resistance by three mechanisms: type A (receptor defect), type B (antireceptor antibodies), and type C (postreceptor defect). It is proposed that, in insulin-resistant states, hyperinsulinemia competes for the insulin-like growth factor receptors on keratinocytes and thus stimulates epidermal growth. In the case of hypercortisolism, as seen in Cushing’s disease, there is induced insulin resistance, which is believed to induce epidermal growth.

7. What does acanthosis nigricans look like?

It is most noticeable in axillary, inframammary, and neck creases, where it appears as hyperpigmented velvety skin that has the appearance of being “dirty” (Fig. 55-1). The tops of the knuckles may also have small papules that resemble finger pebbles, except that they are more pronounced (Fig. 55-2).

8. What is diabetic dermopathy?

Diabetic dermopathy (shin spots or pretibial pigmented patches) is a common affliction of diabetic patients that initially manifests as erythematous to brown to brownish-red macules that typically measure 0.5 to 1.5 cm, with variable scale on the pretibial surface (Fig. 55-3). The lesions are typically asymptomatic but are occasionally pruritic or are associated with a burning sensation. Patients with diabetic dermopathy are more likely to have retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. The lesions heal with varying degrees of atrophy and hyperpigmentation over 1 to 2 years. The pathogenesis is unknown, but skin biopsies from the lesions demonstrate diabetic microangiopathy characterized by a proliferation of endothelial cells and thickening of the basement membranes of arterioles, capillaries, and venules associated with deposition of hemosiderin. Although many physicians attribute these lesions to trauma, this view is not supported by an unusual study in which patients with diabetes mellitus failed to develop lesions after they were struck on the pretibial surface with a hard rubber hammer. Diabetic dermopathy has no known effective treatment.

9. What is necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum?

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is a disease that most commonly occurs on the pretibial areas, although it may occur at other sites. It is more common in women. Early lesions manifest as nondiagnostic erythematous papules or plaques that evolve into annular lesions characterized by a yellowish or yellowish-brown color, dilated blood vessels, and central epidermal atrophy. Developed lesions are characteristic and usually can be diagnosed by clinical appearance. Less commonly, ulcers may develop. Biopsies are usually diagnostic and demonstrate palisaded granulomas that surround large zones of necrotic and sclerotic collagen. Additional findings include dilated vascular spaces, plasma cells, and increased dermal fat. The pathogenesis is not known, but proposed causes include immune complex vasculitis and a platelet aggregation defect.

10. What is the relationship of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum with diabetes mellitus?

In a major study of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, 62% had diabetes. Approximately one half of the nondiabetic patients had abnormal glucose tolerance tests, and almost one half of the nondiabetic patients gave a family history of diabetes. However, necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is present in only 0.3% of patients with diabetes. The term necrobiosis lipoidica is used for patients who have the disorder without associated diabetes. Because of the strong association between these conditions, patients who present with necrobiosis lipoidica should be screened for diabetes; patients who test negative should be reevaluated periodically.

11. How should necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum be treated?

Necrobiosis lipoidica occasionally may resolve without treatment. It does not seem to respond to treatment of diabetes in new cases or to tighter control of established diabetes. Early lesions may respond to treatment with potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids. More severe cases may respond to oral treatment with stanozolol, niacinamide, pentoxifylline, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, or photodynamic therapy. Severe cases with recalcitrant ulcers may require surgical grafting.

12. Are skin infections more common in diabetic patients than in control populations?

Yes, but skin infections are probably not as common as most medical personnel believe. Studies show that an increased incidence of skin infections strongly correlates with elevated levels of mean plasma glucose.

13. What are the most common bacterial skin infections associated with diabetes mellitus?

The most common serious skin infections associated with diabetes mellitus are related to diabetic foot and amputation ulcers. One autopsy study revealed that 2.4% of all diabetic patients had infectious skin ulcerations of the extremities compared with 0.5% of a control population. Even though there are no well-controlled studies, it is believed that staphylococcal skin infections, including furunculosis and staphylococcal wound infections, are more common and serious in diabetic patients. Erythrasma, a benign superficial bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, was present in 47% of adult diabetic patients in one study. Clinically, erythrasma manifests as tan to reddish-brown lesions with slight scale in intertriginous areas such as the groin. Because the organisms produce porphyrins, the diagnosis can be made by demonstrating a spectacular coral red fluorescence with Wood’s lamp.

14. What is the most common fungal mucocutaneous infection associated with diabetes mellitus?

The most common mucocutaneous fungal infection associated with diabetes is candidiasis, usually caused by Candida albicans. Women are particularly prone to vulvovaginitis. One study demonstrated that two thirds of all diabetic patients have positive cultures for Candida albicans. In women with signs and symptoms of vulvitis, the incidence of positive cultures approaches 99%. Similarly, positive cultures are extremely common in diabetic men and women who complain of anal pruritus. Other mucocutaneous forms of candidiasis include thrush, perlèche (angular cheilitis), intertrigo, erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica chronica (Fig. 55-4), paronychia (infection of the soft tissue around the nail plate), and onychomycosis (infection of the nail). The mechanism appears to be related to increased levels of glucose that serve as a substrate for Candida species to proliferate. Patients with recurrent cutaneous candidiasis of any form should be screened for diabetes.

15. Why are diabetic patients in ketoacidosis especially prone to mucormycosis?

Some Zygomycetes, including Mucor, Mortierella, Rhizopus, and Absidia species, are thermotolerant, prefer an acid pH, grow rapidly in the presence of high levels of glucose, and are among the few fungi that use ketones as a growth substrate. Thus, diabetic patients with ketoacidosis provide an ideal environment for the proliferation of these fungi and are especially prone to develop rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Fortunately, these fulminant and often fatal fungal infections are rare.

16. Are any skin complications associated with the treatment of diabetes mellitus?

Yes. Adverse reactions to injected insulin are relatively common. The reported incidence varies from 10% to 56%, depending on the study. In general, these complications may be divided into three categories: reactions resulting from faulty injections (e.g., intradermal injection), idiosyncratic reactions, and allergic reactions. Several types of allergic reactions have been described, including localized and generalized urticaria, Arthus reactions, and localized delayed hypersensitivity. Oral hypoglycemic agents occasionally may produce adverse cutaneous reactions, including photosensitivity, urticaria, erythema multiforme, and erythema nodosum. Chlorpropamide in particular may produce a flushing reaction when it is consumed with alcohol.

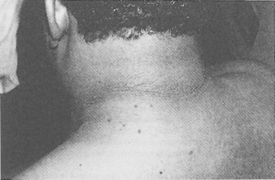

17. What is scleredema adultorum?

Scleredema adultorum is a woody induration that most commonly manifests on the posterior neck, upper back, and shoulders. Less commonly, it may be more extensive and involve the face, abdomen, and extremities. It is most commonly associated with insulin-dependent diabetes and is less commonly associated with monoclonal gammopathies and streptococcal infections. Biopsies demonstrate increased dermal collagen and hyaluronic acid (dermal mucin). The pathogenesis is not understood. When associated with insulin-dependent diabetes, scleredema adultorum is chronic and recalcitrant to therapy.

18. What are the most important cutaneous manifestations of the hypothyroid state?

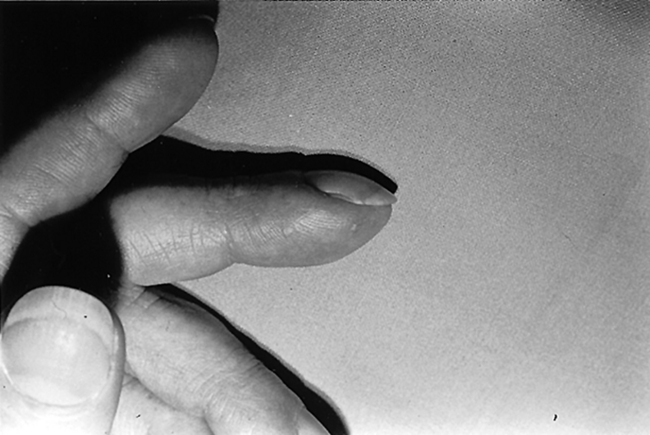

Generalized myxedema is the most characteristic cutaneous sign of hypothyroidism. Other skin findings include xerosis (dry skin), follicular hyperkeratosis (Fig. 55-5), diffuse hair loss (especially the outer one third of the eyebrows), dry and brittle nails, yellowish discoloration of the skin, and thyroid acropachy (thickening of the distal fingers). These skin changes are all reversible with appropriate thyroid replacement.

19. Why do hypothyroid patients often have yellow skin?

The yellow color results from the accumulation of carotene (carotenoderma) in the top layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum). Carotene is excreted by both the sweat and the sebaceous glands and tends to concentrate on the palms, soles, and face. The increased levels of carotene are probably secondary to impaired hepatic conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A.

20. What are the clinical findings in generalized myxedema?

Generalized myxedema is characterized by pale, waxy, edematous skin that does not demonstrate pitting. These changes are most noticeable in the periorbital area but may also be observed in the distal extremities, lips, and tongue (Fig. 55-6).

21. What is the pathogenesis of generalized myxedema?

The skin demonstrates an increased accumulation of dermal acid mucopolysaccharides, of which hyaluronic acid (ground substance) is the most important. Studies also have demonstrated that an increased transcapillary escape of serum albumin into the dermis adds to the edematous appearance. Neither of these changes is permanent; both are reversible with replacement therapy.

22. What is the difference between generalized myxedema and pretibial myxedema?

Generalized myxedema is associated with only the hypothyroid state, whereas pretibial myxedema is characteristically associated with Graves’ disease. Patients with pretibial myxedema may be hypothyroid, hyperthyroid, or euthyroid when the skin disorder appears. The pathogenesis has not been proved, but it has been demonstrated that serum from patients with pretibial myxedema will stimulate the production of acid mucopolysaccharides of fibroblasts. Fibroblasts from the pretibial area are more sensitive to stimulation than are fibroblasts from other areas; this accounts for the tendency for these lesions to occur in pretibial areas. The nature of this circulating factor is unknown, but stimulatory thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor autoantibodies are thought to be the most likely candidate. Investigators have also postulated that activated T cells induce both fibroblast proliferation and the production of acid mucopolysaccharides.

23. What are the clinical manifestations of pretibial myxedema?

Pretibial myxedema occurs in approximately 3% to 5% of patients with Graves’ disease. Most patients have associated exophthalmos. Thyroid acropachy is also present in 1% of patients with Graves’ disease (Fig. 55-7). Clinically, pretibial myxedema is characterized by edematous, indurated plaques over the pretibial areas, although other sites of the body also may be involved. The plaques are usually sharply demarcated, but diffuse variants are also reported. The overlying skin surface is usually normal, although it may be studded with smaller papules. The color varies from skin colored to brownish red (Fig. 55-8). Overlying hypertrichosis may be present on rare occasions. Histologically, pretibial myxedema demonstrates massive accumulation of dermal hyaluronic acid.

24. How is pretibial myxedema treated?

Studies comparing different treatment modalities have not been performed. Because the condition is not harmful to patients and because it may resolve spontaneously, treatment is not always indicated. Many cases respond to potent topical corticosteroids under occlusion or intralesional corticosteroids. More extensive cases may be treated with oral systemic corticosteroids or rituximab in combination with plasmapheresis. Treatment of the thyroid disease does not affect the cutaneous findings.

25. What are the skin manifestations of hyperthyroidism?

Studies have shown that as many as 97% of all patients with hyperthyroidism develop skin manifestations. Common cutaneous findings include cutaneous erythema, evanescent flushing, excoriations, smooth skin, hyperpigmentation, moist skin (from increased sweating), pretibial myxedema, pruritus (itching), and warm skin. Nails are often brittle and may separate from the underlying bed (onycholysis). The hair also may be thinner than normal.

26. What effect does obesity have on skin function and physiology?

Obesity effects skin function and physiology in many ways. The skin barrier function is altered in obese individuals, who show a significantly increased transepidermal water loss. The elevation of androgens, insulin, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor seen in obese patients is related to an increase in sebaceous gland function and sebum production, thus exacerbating diseases such as acne vulgaris. The activity of apocrine and eccrine sweat glands is also increased in obese patients. Lymphatic flow is impeded in obese individuals, and this leads to accumulation of protein-rich lymphatic fluid in the subcutaneous tissue that, in turn, leads to lymphedema. In animal studies, obesity is associated with altered collagen structure and function and with impaired wound healing.

27. What are some of the cutaneous manifestations of obesity?

Obese patients have myriad cutaneous manifestations, including changes related to insulin resistance, as well as infectious, mechanical, and inflammatory conditions. These include acanthosis nigricans (discussed earlier), acrochordons (skin tags), keratosis pilaris, striae distensae, and hidradenitis suppurativa.

28. Does obesity aggravate any skin diseases?

Yes. Obesity aggravates multiple skin diseases, including intertrigo, hidradenitis suppurativa, cellulite, psoriasis, and chronic venous insufficiency. Bacterial skin infections are also aggravated by obesity. These range from superficial infections, such as folliculitis, to deep infections, such as cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis.

Anderson, CK, Miller, OF. Triad of exophthalmos, pretibial myxedema, and acropachy in a patient with Graves’ disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:970–972.

Bello, YM, Phillips, TJ, Necrobiosis lipoidica. indolent plaques may signal diabetes. Postgrad Med 2001;109:93–94.

Ferringer, T, Miller, F. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:483–492.

Hollister, DS, Brodell, RT, Finger “pebbles”. a dermatologic sign of diabetes mellitus. Postgrad Med 2000;107:209–210.

Levy, L, Zeichner, JA. Dermatologic manifestations of diabetes. J Diabetes. 2012;4:68–76.

Lipsky, BA, Berendt, AR. Principles and practice of antibiotic therapy of diabetic foot infections. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16(Suppl 1):S42–S46.

Niepomniszcze, H, Amad, RH. Skin disorders and thyroid diseases. J Endocrinol Invest. 2001;24:628–638.

Pirotta, SS, Johnson, JD, Young, G, et al. Bullosis diabeticorum. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 1995;85:169–171.

Rammaert, B, Lanternier, F, Poirée, S, et al, Diabetes and mucormycosis. a complex interplay. Diabetes Metab 2012;38:193–204.

Shemer, A, Bergman, R, Linn, S, et al. Diabetic dermopathy and internal complications in diabetes mellitus. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:113–115.

Stoddard, ML, Blevins, KS, Lee, ET, et al, Association of acanthosis nigricans with hyperinsulinemia compared with other selected risk factors for type 2 diabetes in Cherokee Indians. the Cherokee Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1009–1014.

Yosipovitch, G, DeVore, A, Dawn, A, Obesity and the skin. skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:901–916.