Chapter 658 Cutaneous Fungal Infections

Tinea Versicolor

Clinical Manifestations

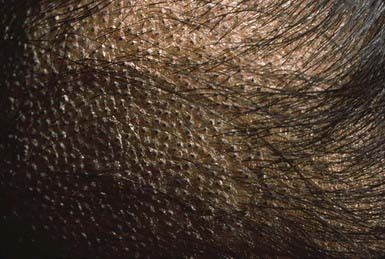

The lesions of tinea versicolor vary widely in color. In white individuals, they are typically reddish brown, whereas in black individuals they may be either hypopigmented or hyperpigmented. The characteristic macules are covered with a fine scale. They often begin in a perifollicular location, enlarge, and merge to form confluent patches, most commonly on the neck, upper chest, back, and upper arms (Fig. 658-1). Facial lesions are common in adolescents; lesions occasionally appear on the forearms, dorsum of the hands, and pubis. There may be little or no pruritus. Involved areas do not tan after sun exposure. A papulopustular perifollicular variant of the disorder may occur on the back, chest, and sometimes the extremities.

Dermatophytoses

Epidemiology

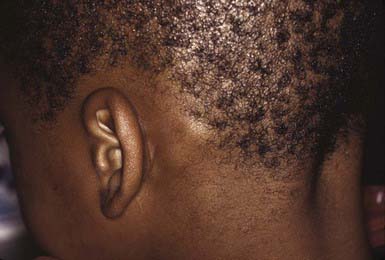

Occasionally, a secondary skin eruption, referred to as a dermatophytid or “id” reaction, appears in sensitized individuals and has been attributed to circulating fungal antigens derived from the primary infection. The eruption is characterized by grouped papules (Fig. 658-2) and vesicles and, occasionally, by sterile pustules. Symmetric urticarial lesions and a more generalized maculopapular eruption also can occur. Id reactions are most often associated with tinea pedis but also occur with tinea capitis.

Tinea Capitis

Clinical Manifestations

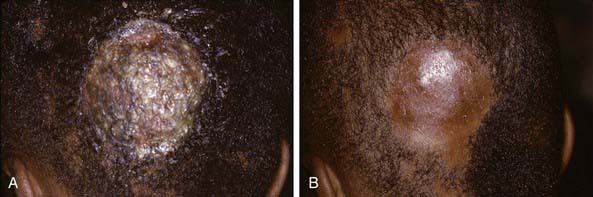

The clinical presentation of tinea capitis varies with the infecting organism. Endothrix infections such as those caused by T. tonsurans create a pattern known as “black-dot ringworm,” characterized initially by many small circular patches of alopecia in which hairs are broken off close to the hair follicle (Fig. 658-3). Another clinical variant manifests as diffuse scaling, with minimal hair loss secondary. It strongly resembles seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or atopic dermatitis (Fig. 658-4). T. tonsurans may also produce a chronic and more diffuse alopecia. Lymphadenopathy is common (Fig. 658-5). A severe inflammatory response produces elevated, boggy granulomatous masses (kerions), which are often studded with pustules (Fig. 658-6A). Fever, pain, and regional adenopathy are common, and permanent scarring and alopecia may result (Fig. 658-6B). The zoophilic organism M. canis or the geophilic organism Microsporum gypseum also may cause kerion formation. The pattern produced by Microsporum audouinii, the most common cause of tinea capitis in the 1940s and 1950s, is characterized initially by a small papule at the base of a hair follicle. The infection spreads peripherally, forming an erythematous and scaly circular plaque (ringworm) within which the infected hairs become brittle and broken. Numerous confluent patches of alopecia develop, and patients may complain of severe pruritus. M. audouinii infection is no longer common in the USA. Favus is a chronic form of tinea capitis that is rare in the USA and is caused by the fungus Trichophyton schoenleinii. Favus starts as yellowish red papules at the opening of hair follicles. The papules expand and coalesce to form cup-shaped, yellowish, crusted patches that fluoresce dull green under a Wood lamp.

Tinea Corporis

Clinical Manifestations

The most typical clinical lesion begins as a dry, mildly erythematous, elevated, scaly papule or plaque that spreads centrifugally and clears centrally to form the characteristic annular lesion responsible for the designation ringworm (Fig. 658-7). At times, plaques with advancing borders may spread over large areas. Grouped pustules are another variant. Most lesions clear spontaneously within several months, but some may become chronic. Central clearing does not always occur (Fig. 658-8), and differences in host response may result in wide variability in the clinical appearance—for example, granulomatous lesions called Majocchi granuloma due to penetration of organisms along the hair follicle to the level of the dermis, producing a fungal folliculitis and perifolliculitis (Fig. 658-9), and the kerion-like lesions referred to as tinea profunda. Majocchi granuloma is more common after inappropriate treatment with topical corticosteroids, especially the superpotent class.

Tinea Pedis

Clinical Manifestations

Most commonly, the lateral toe webs (3rd to 4th and 4th to 5th interdigital spaces) and the subdigital crevice are fissured, with maceration and peeling of the surrounding skin (Fig. 658-10). Severe tenderness, itching, and a persistent foul odor are characteristic. These lesions may become chronic. This type of infection may involve overgrowth by bacterial flora, including Kytococcus sedantarius, Brevibacterium epidermidis, and gram-negative organisms. Less commonly, a chronic diffuse hyperkeratosis of the sole of the foot occurs with only mild erythema (Fig. 658-11). In many cases, two feet and one hand are involved. This type of infection is more refractory to treatment and tends to recur. An inflammatory vesicular type of reaction may occur with T. mentagrophytes infection. This type is most common in young children. The lesions involve any area of the foot, including the dorsal surface, and are usually circumscribed. The initial papules progress to vesicles and bullae that may become pustular (Fig. 658-12). A number of factors, such as occlusive footwear and warm, humid weather, predispose to infection. Tinea pedis may be transmitted in shower facilities and swimming pool areas.

Tinea Unguium

Clinical Manifestations

The most superficial form of tinea unguium (i.e., white superficial onychomycosis) is due to T. mentagrophytes. It manifests as irregular single or numerous white patches on the surface of the nail unassociated with paronychial inflammation or deep infection. T. rubrum generally causes a more invasive, subungual infection that is initiated at the lateral distal margins of the nail and is often preceded by mild paronychia. The middle and ventral layers of the nail plate, and perhaps the nail bed, are the sites of infection. The nail initially develops a yellowish discoloration and slowly becomes thickened, brittle, and loosened from the nail bed (Fig. 658-13). In advanced infection, the nail may turn dark brown to black and may crack or break off.

Candidal Infections (Candidosis, Candidiasis, and Moniliasis) (Chapter 226)

Candidal Diaper Dermatitis

The primary clinical manifestation consists of an intensely erythematous, confluent plaque with a scalloped border and a sharply demarcated edge. It is formed by the confluence of numerous papules and vesicular pustules. Satellite pustules, those that stud the contiguous skin, are a hallmark of localized candidal infections. The perianal skin, inguinal folds, perineum, and lower abdomen are usually involved (Fig. 658-14). In males, the entire scrotum and penis may be involved, with an erosive balanitis of the perimeatal skin. In females, the lesions may be found on the vaginal mucosa and labia. In some infants, the process is generalized, with erythematous lesions distant from the diaper area. In some cases, the generalized process may represent a fungal id (hypersensitivity) reaction.

Intertriginous Candidosis

Intertriginous candidosis occurs most often in the axillae and groin, on the neck (Fig. 658-15), under the breasts, under pendulous abdominal fat folds, in the umbilicus, and in the gluteal cleft. Typical lesions are large, confluent areas of moist, denuded, erythematous skin with an irregular, macerated, scaly border. Satellite lesions are characteristic and consist of small vesicles or pustules on an erythematous base. With time, intertriginous candidal lesions may become lichenified, dry, scaly plaques. The lesions develop on skin subjected to irritation and maceration. Candidal superinfection is more likely to occur under conditions that lead to excessive perspiration, especially in obese children and in children with underlying disorders, such as diabetes mellitus. A similar condition, interdigital candidosis, commonly occurs in individuals whose hands are constantly immersed in water. Fissures occur between the fingers and have red denuded centers, with an overhanging white epithelial fringe. Similar lesions between the toes may be secondary to occlusive footwear. Treatment is the same as for other candidal infections.

Perianal Candidosis

Perianal dermatitis develops at sites of skin irritation as a result of occlusion, constant moisture, poor hygiene, anal fissures, and pruritus due to pinworm infestation. It may become superinfected with C. albicans, especially in children who are receiving oral antibiotic or corticosteroid medication. The involved skin becomes erythematous, macerated, and excoriated, and the lesions are identical to those of candidal intertrigo or candidal diaper rash. Application of a topical antifungal agent in conjunction with improved hygiene is usually effective. Underlying disorders such as pinworm infection must also be treated (Chapter 285).

Andrews MD, Burns M. Common tinea infections in children. Am Fam Physician. 2008;15:1415-1420.

Elewski BE, Caceres HW, DeLeon L, et al. Terbinafine hydrochloride oral granules versus oral griseofulvin suspension in children with tinea capitis: results of two randomized, investigator-blinded, multicenter, international, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:41-54.

Panackal AA, Halpern EF, Watson AJ. Cutaneous fungal infections in the United States: analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), 1995–2004. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:704-712.