Chapter 39 Cutaneous Carcinoma

Cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are the most common malignant neoplasms in the world and occur at epidemic rates in some countries such as Australia.1 Collectively, these two carcinomas account for most (95%) patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and are markedly more common than malignant melanomas, which account for only 5% of all skin malignancies. Most BCCs and SCCs occur in individuals older than 50 years old with fair complexions or outdoor occupations mostly on the sun-exposed head and neck or extremities, although NMSC does occur in younger people. Skin cancers may be disfiguring and associated with local morbidity in certain locations but are rarely lethal. The frequency of BCC is four times that of SCC, and BCCs tend to be more indolent and rarely metastasize.

Other NMSCs that are infrequently encountered include Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) and adnexal cancers. MCC, also known as primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma, is a rare small cell carcinoma originally described by Toker in 1972.2 Sebaceous gland carcinomas account for less than 1% of all skin neoplasms.3 Eccrine or sweat gland carcinomas are very rare, estimated to account for less than 0.01% of malignant epithelial neoplasms of the skin.

Etiology And Epidemiology

The main etiologic factor for cutaneous carcinoma is sun exposure in individuals, usually whites, whose skin is susceptible to the chronic carcinogenic effect of ultraviolet (UV) light.4 Approximately 90% of NMSC can be attributed to excessive sun exposure. Other, less common etiologic factors include exposure to chemical carcinogens (e.g., arsenic, tar, anthracene, and crude paraffin oil), chronic irritation or inflammation, and ionizing radiation.

The incidence and aggressiveness of SCC and MCC (both immunogenic carcinomas) are markedly increased in individuals with compromised immune function, including patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia5 and organ transplant recipients with iatrogenic immunosuppression.6 In contrast, the incidence of BCC is not increased and the outcome is similar as for immunocompetent patients.

Some genetic syndromes are also associated with a higher risk of developing skin carcinoma. Individuals with xeroderma pigmentosum are prone to developing BCC and SCC at a very young age because of defective repair of UV light–induced DNA damage.7 These patients usually die in their early 20s from disseminated SCC or melanoma. The basal cell nevus syndrome (or Gorlin syndrome) is a genetic form of BCC inherited through an autosomal dominant gene.8 Individuals with epidermodysplasia verruciformis tend to develop nodules of SCC within large verrucous plaques in the 3rd and 4th decades of life.

Prevention And Screening

Unprotected sun exposure, especially during the summer, is the main determinant for the subsequent development of skin cancer. Children and adolescents should be especially educated in regard to sun protection. The damage of excessive UV exposure is irreversible, but despite this adults can still reduce their risk by avoiding further excessive UV exposure. Authorities worldwide have made recommendations regarding appropriate measures. A panel of the American College of Preventive Medicine issued practice policy statements with regard to skin cancer prevention, as summarized by Hill and Ferrini,9 and recommended preventive measures to reduce skin cancer to include avoidance of sunlight exposure—particularly limiting time spent outdoors between 10 A.M. and 3 P.M.—and wearing protective physical barriers, such as hats and clothing. If sun exposure cannot be limited because of occupational, cultural, or other factors, the use of sunscreens that are either opaque or that block UVA and UVB radiation is recommended. The use of tanning booths is also a factor in the risk of developing skin cancer, and guidelines regarding their appropriate use should be followed.

Clinical Manifestations, Pathobiology, And Pathways Of Spread

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

BCC constitutes approximately 80% of all NMSC and is the most common malignancy worldwide. Most BCCs arise on the sun-exposed head and neck (80% to 85%); lesions occur less frequently on the trunk or extremities. Lesions may manifest as an asymptomatic nodule, a pruritic plaque, or a bleeding ulcer that characteristically waxes and wanes.10,11 Many patients treated for BCC develop at least one or more further BCCs.12 Careful evaluation of sun-exposed skin should be part of any follow-up examination.

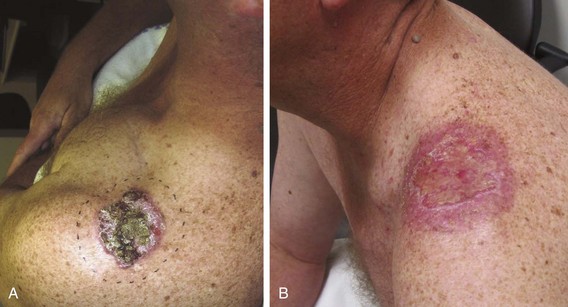

BCC has numerous variants, each of which has distinctive clinical and histologic features and natural history. The characteristics of commonly occurring types are briefly summarized. Nodular BCC, colloquially referred to as rodent ulcer, is the most frequently observed variant and accounts for approximately 50% of all lesions (Fig. 39-1). This type of skin cancer begins as a distinct papule that may develop central umbilication, progressing to central ulceration as the lesion grows. The margins of the lesion appear pearly (pale and translucent) and contain enlarged capillaries (telangiectasia). Histologic features include the presence of large islands of monomorphous basaloid cells, varying in size and shape, embedded in a fibroblastic stroma in the dermis. The basaloid cells have large, oval hyperchromatic nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and no intercellular bridges. The peripheral cell layer of the aggregate frequently shows palisading, whereas central cells are less organized. Nodular BCC may show a varying degree of pigmentation (blue, brown, or black), depending on the number of melanocytes present in the lesion, and may be difficult to differentiate clinically from malignant melanoma.13

Superficial BCC manifests as red, scaly macules with indistinct margins, usually located on the trunk (Fig. 39-2). It enlarges into a crusted, erythematous patch without induration that may be difficult to differentiate clinically from solar keratosis, psoriasis, SCC in situ, or extramammary Paget’s disease. Histologic examination shows multiple foci of buds of neoplastic cells with peripheral palisading originating from the undersurface of the epidermis.10

Morpheaform (sclerosing) BCCs appear as single, flat, indurated, ill-defined macules. The lesions generally have a smooth, shiny surface that becomes depressed as it grows into a plaque. It is characterized histologically by the presence of small groups and narrow strands of basaloid cells embedded in a dense, fibrous connective tissue; there is little peripheral palisading.14 Perineural invasion is often reported to be present.

Infiltrative BCC has an opaque yellowish appearance and blends subtly with the surrounding skin.14 Histologically, the lesion is characterized by poorly circumscribed spiky cell aggregates in the superficial portion and the main bulk, consisting of strands of neoplastic cells infiltrating the reticular dermis and subcutis.

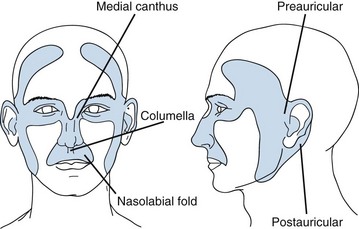

Location is important in defining high-risk BCC. The midface, or so-called H zone (Fig. 39-3), including the periauricular region, glabella, medial canthus, nose, nasolabial region, and columella, contains embryonal fusion planes.15 The extent of tumors in this region is frequently underestimated, leading to inadequate surgical excision, especially deep, and a higher rate of local recurrence. Histologic examination often reveals extensive infiltration of deeper structures by small nests of undifferentiated basal cells. This type of lesion may invade the orbit, nose, and maxilla, resulting in significant deformity. It should be readily recognized and treated promptly often necessitating extensive surgery with or without adjuvant RT.

Biology and Pattern of Spread

The biologic behavior of BCC varies with the histologic type. A superficial BCC may remain stable for a long time or enlarge gradually over many years to become a nodulo-ulcerative variant. Nodular BCC grow slowly over many years by peripheral and deep invasion, particularly along embryonal fusion planes, and perineural spread. Morpheaform, infiltrative, and terebrant BCCs are more aggressive variants that may spread through peripheral invasion or infiltration of deeper structures, or both. Perineural (or neurotropic) invasion in BCC is rare, occurring in only 2% to 3% of patients, and generally occurs in the setting of recurrent disease or in morpheaform histology.16 Lesions located around the orbit may gain access to the orbit via the first or second division of the trigeminal nerve (or fifth cranial nerve).

BCCs rarely spread to the regional lymph nodes or distant organs with an overall incidence of metastasis less than 0.01%.17 Most metastases occur in the regional lymph nodes with distant spread usually preceded by regional metastasis. Regional disease typically develops with large, ulcerated lesions in the head and neck that have recurred after repeated surgery and RT.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

SCC arises from keratinocytes of the epidermis. This type of NMSC most commonly develops from skin exhibiting solar (or UV) damage. Actinic (or solar) keratosis (intradermal malignant neoplasm) is generally a precursor or premalignant lesion; at least 50% to 60% of all invasive SCCs arise from actinic keratoses. Despite this, only a few (<5%) actinic keratoses actually progress to invasion. In a large study of 169 patients with 7784 documented actinic keratoses, the risk of malignant progression was reported in 2.6% at 4 years.18 Less frequently, SCC occurs from other preexisting skin lesions, such as arsenic keratosis, a thermal burn scar, or a chronic ulcer. Rarely, it arises from normal-appearing skin.13

Clinically, SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease) manifests as a soft, erythematous, scaly, well-circumscribed patch (Fig. 39-4). Superficial carcinoma manifests as a scaly, crusted plaque or ulcer with a verrucous or papillate border, and infiltrating SCC manifests as a firm, ulcerated mass with an elevated nodular border (Fig. 39-5).

Biology and Pattern of Spread

SCC generally has a more aggressive course than BCC. Carcinoma in situ (or Bowen’s disease) may evolves gradually into superficial carcinoma in 5% of cases.19 Untreated, it may progress further into an infiltrating type that invades the surrounding and underlying structures. The rate of progression depends on the degree of cellular differentiation.

The risk of developing metastases, usually nodal, is markedly higher in SCC than in BCC. However, most immunocompetent patients with small (<2 cm), thin (<4 to 5 mm thick), nonrecurrent lesions are at low (<5%) risk of developing nodal metastases. Patients not meeting these criteria can be considered high-risk patients (>10% risk), and appropriate awareness and management are required.20 Recurrent lesions in close proximity (forehead, temple, ear, cheek) to the parotid gland increase this risk (Fig. 39-6). Data suggest that tumor thickness greater than 6 mm is a powerful, independent predictor of patients at risk for regional metastases.21

The most frequent sites for the development of metastatic cutaneous SCC are the parotid gland, the cervical lymph nodes, or both.22 In 20% to 25% of cases, an obvious index lesion is not identified. Invariably, these patients have a long-standing history of actinopathy with previous NMSC. The development of distant metastases (e.g., lung, liver) rarely occurs as a first site of relapse and is more often encountered after initial treatment for nodal metastases.

Metastatic cutaneous SCC occurs less frequently in other nodal regions, such as the axilla and groin. Although difficult to quantify, the ratio of metastatic head and neck SCC to non–head and neck SCC is approximately 9 : 1. There are much fewer published data on the management of these patients, but analogous generalizations from the evidence on parotid and neck nodal metastases suggest operable patients should have surgical resection, and many have unfavorable features, such as extranodal spread and incomplete margins, and require adjuvant RT.23 The combination of surgery and adjuvant RT often leads to extremity lymphedema, and patients should be warned about this.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

MCC is a small cell cutaneous malignancy that often manifests as a rapidly enlarging firm, painless, pink-red, dermal-based nodule, most frequently on the head and neck or extremities in older (>60 to 70 years old) individuals (Fig. 39-7). In contrast to other types of NMSC, MCCs frequently arise in women. Diagnosis is often delayed by clinicians because of the uncommon nature of this disease. The median size of the primary lesion at diagnosis is approximately 2 cm, and the incidence of clinical nodal involvement at presentation is approximately 20% to 25%, although the risk of harboring occult nodal disease is high (30% to 40%).24 Based on the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, the annual incidence in men is 0.34 per 100,000 with most patients older than 65 years and white (94%). In this study, slightly less than half (46%) of all lesions occurred in the head and neck, and at diagnosis half of all patients had localized disease with nodal metastases present in approximately 25%.25

The cell of origin of this neoplasm is thought to be the dermal neurotactile cell arising from the neural crest first described by Merkel.26 The lesion usually involves the reticular dermis and subcutaneous tissues, with minimal extension to the papillary dermis and sparing of the epidermis. Vascular and lymphatic permeation is common, and clinically such permeation often manifests as in-transit metastasis. The neoplastic cells exhibit cytoplasmic extensions and small, uniform, membrane-bound neurosecretory granules on ultramicroscopic examination.27 Several immunohistochemical markers have been identified in MCC. The neoplastic cells stain most consistently with polyclonal antisera to neuron-specific enolase and calcitonin, monoclonal antibody to neurofilament, and cytokeratin (CK 20 positive).28 More recent evidence suggests a possible viral association in the development of MCC. In the study by Feng and colleagues,29 8 of 10 tumors were found to contain Merkel cell polyomavirus compared with only 8% in control tissues.

Biology and Pattern of Spread

The results of many retrospective studies confirm that MCC has an aggressive course characterized by propensity for contiguous spread, reflected in high local recurrence rates after wide surgical excision alone and a high incidence of nodal involvement and hematogenous dissemination.29 Most series document a cancer-specific death rate of around 30%.30 Patients may also present with metastatic nodal disease without an obvious index lesion. In one large study, 19% of patients had metastatic disease to nodes from an unknown primary.31 MCC is a highly immunogenic carcinoma, and immunosuppressed patients (organ transplant recipients) and patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia are at higher risk of developing MCC and having a poor outcome. In a study of 41 organ transplant recipients with MCC, many were younger, most (68%) had nodal disease at diagnosis, and almost 60% died of their disease.32

Adnexal Carcinoma

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

Sebaceous carcinomas are rare (approximately 400 reported) and arise most commonly (75% of cases) from the sebaceous glands of the ocular adnexa, the meibomian glands in the tarsus or glands of Zeis at the lid margin, and the caruncle. Extraocular locations, in decreasing frequency, are head and neck region, trunk and extremities, and external genitalia.3 Histologically, these carcinomas are composed of dermal-based lobules and cords of tumor cells, with varying degrees of sebaceous differentiation and infiltration into the surrounding tissues. Differentiated cells contain foamy or vacuolated, slightly basophilic cytoplasm, whereas less differentiated cells contain more deeply basophilic cytoplasm. Clinical and pathologic features that indicate a poor prognosis include size of the primary lesion (>1 cm is associated with 50% mortality rate), vascular and lymphatic invasion, poor sebaceous differentiation, highly infiltrative growth pattern, and intraepithelial carcinomatous changes in the overlying epithelia.33

Biology and Pattern of Spread

Sebaceous carcinoma behaves more aggressively than SCC, with a propensity for nodal and hematogenous spread.34 Of the 104 patients registered by the Ophthalmic Pathology of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 23 patients (22%) experienced local recurrence once, and 11 patients experienced local recurrence two or more times. Metastatic disease was the cause of death in 23 patients.33

Eccrine Carcinoma

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

Histologically, eccrine or sweat gland carcinomas may resemble carcinomas of the breast, bronchus, and kidney and are difficult to differentiate from cutaneous metastases. Many histologic variants are reported and include ductal eccrine carcinoma, mucinous eccrine carcinoma, porocarcinoma, syringoid eccrine carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma.35

Biology and Pattern of Spread

Eccrine carcinoma also has more aggressive behavior than BCC and SCC. In a series of 14 patients who underwent surgical excision with free microscopic margins, 11 developed at least one local recurrence, and 5 failed at regional nodes or distant sites. One patient died of uncontrolled local relapse, and four died of distant metastasis 2 months to 10 years after diagnosis.35 Apocrine carcinoma arises most commonly from apocrine glands of the axilla, but it can originate from apocrine glands of the vulva and eyelids and from ceruminal glands of the external auditory canal. It manifests clinically as a red-purple single or multinodular, firm or cystic dermal mass in elderly individuals. Because of its rarity, the natural history of apocrine carcinoma is not well known. Nodal and distant spread has been reported.36,37

Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a rare locally aggressive carcinoma that belongs to the spectrum of adnexal carcinomas and most often arises on the head and neck.38 It usually grows slowly over years and often is deeply invasive when diagnosed. It arises equally in males and females and tends to occur in adults 55 to 60 years old and occasionally in children.

Histologically, the tumor is composed of keratin horn cysts, nests, or cords of basaloid cells that are usually more prominent in the superficial dermis. Tumor strands and cystically dilated tubules are arranged in sold islands and embedded in deeper desmoplastic stroma. The cells usually show no atypia or mitoses, and the differential diagnosis may include trichoadenoma, syringoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, or morpheaform BCC.39

Patient Evaluation And Staging

Clinical evaluation of skin cancers consists of inspection and palpation of the involved area and the regional lymph nodes. Symptoms suggestive of perineural invasion, such as pain, tingling, and hypesthesia, should be specifically sought from the patient. Up to 60% of patients with perineural invasion may be clinically asymptomatic, and a crawling sensation on the skin termed formication is very suggestive for sensory nerve involvement.40 The most common primary sites associated with perineural invasion are the frontozygomatic (supraorbital nerve) and infraorbital (infraorbital nerve) regions. Patients may present with a cranial nerve palsy as the first sign of perineural invasion. Facial nerve involvement is usually preceded by muscle fasciculations followed by frank paralysis.41

Imaging studies (chest radiography, computed tomography [CT], or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) generally are not required in most patients with NMSC but should be obtained as indicated (e.g., clinically suspicious lymph nodes). Lymph node metastasis and bone involvement are best assessed with contrast-enhanced CT scan acquired with soft tissue and bone windows (Fig. 39-8). MRI, with and without contrast enhancement and fat suppression, should be obtained for all patients in whom perineural invasion is suspected, with the findings of an enlarged or abnormally enhancing nerve raising the possibility of perineural invasion.42 Patients often need to undergo biopsy of the suspected nerve to confirm the diagnosis.43

Staging of Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Official staging systems are available for BCC and SCC but have been criticized for lacking clinical and prognostic relevance, especially for patients with SCC.44,45 More recent changes include reporting of important pathologic high-risk features, such as tumor depth and the presence of perineural invasion. The previous American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM (primary tumor, regional nodes, metastases) staging systems were based primarily on clinical findings and were of limited usefulness. In regard to T stage, only maximum horizontal dimension determined stages T1 to T3. The newer staging system (AJCC seventh edition) incorporates important clinicopathologic factors and does not rely purely on size as a T stage determinant. High-risk features can now upstage a tumor, for example from T1 to T2, even if horizontal size is unchanged.

Similar to previous flaws in staging patients with the primary, or T, stage, patients with nodal metastases from SCC were assigned an N stage via a flawed staging system with all patients indiscriminately assigned as stage N1 regardless of metastatic nodal size, number, or presence of extranodal spread.46 O’Brien and colleagues47 proposed a staging system for metastatic SCC to the parotid or neck that categorizes N (neck) and P (parotid) stage based on the aforementioned variables. The new AJCC system now delineates using number and size of nodes.

Staging of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A staging system developed by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center separates patients into patients with primary lesions less than 2 cm (stage I) and patients with primary lesions greater than or equal to 2 cm (stage II). Patients with nodal disease are stage III, and patients with distant disease are stage IV. A few (10% to 15%) patients present with metastatic nodal disease without an obvious index lesion.48 This staging system is prognostic with the presence of nodal metastases independently predicting for a worse outcome. In the current AJCC TNM staging system, primary size and clinical and pathologic nodal status are incorporated into new group staging.

Primary Treatment and Results

Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Primary Tumor

Overall, surgery is preferred for most patients. Simple procedures can yield high local control probability for patients with small lesions. Composite resection is necessary, however, for patients with extensive, deeply invasive tumors. Younger patients who have years of future exposure to sunlight are also better managed by surgery than by RT, although in certain cases RT may still be considered a better option.49 In numerous settings, such as close or positive margins or the presence of perineural invasion, postoperative RT may be beneficial to reduce the risk of local recurrence.

The indications for postoperative (adjuvant) RT include the presence of positive surgical margins, perineural spread, invasion of bone and cartilage, lymph node metastasis, and extensive skeletal muscle infiltration. Relevant information including size, depth of invasion, differentiation, presence or absence of perineural invasion, and margin status should be obtained from the pathologist. The University of Florida group reported a 100% local control rate in medial canthus BCC treated with adjuvant RT in the setting of positive margins when prescribing a median dose of 50 Gy in 20 daily fractions.50

Primary (or definitive) RT is most often indicated for lesions on and around the nose, lower eyelids, medial canthus, and ears, where it yields better functional and cosmetic results than surgery51 (Fig. 39-9). Extensive lesions of the cheek, lip, and oral commissures that would require full-thickness resection may also be better irradiated. The lower lip is especially suited for RT when surgery may result in microstomia or require complex reconstruction for lesions occupying more than one-third of the lip. Patients can be easily treated with orthovoltage RT after insertion of a lead oral cavity shield with expected cure rates similar to surgery.52

The overall local control rate of all sizes and types of cutaneous carcinoma treated with various modalities is 80% to 90%. RT is an excellent treatment option for patients in whom other modalities may have failed or are considered less optimal. In a series from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center of patients with SCC of the eyelid (Fig. 39-10) treated with definitive RT, an excellent 5-year local control of 89% was achieved.53

Patients with recurrent lesions (vs. de novo lesions) and with SCC (vs. BCC) have lower rates of local control. Similarly, as lesions increase in size, rates of local control decrease. In one study of patients with locally advanced (>T2) SCC and BCC, 4-year locoregional control rates were 86% and 58% for SCC and BCC.54 Despite this, RT may still remain the best option.

Regional Nodes

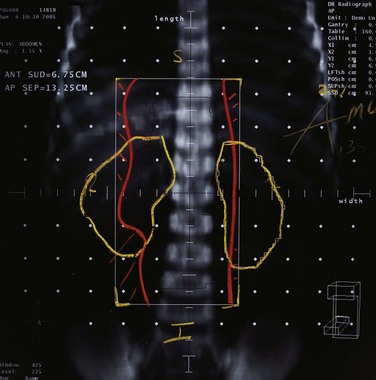

Elective nodal treatment is not indicated for cutaneous BCC or low-risk SCC because of the low incidence of lymphatic spread. However, certain patients with high-risk SCC may warrant elective treatment (surgery or RT) of clinically node-negative regional nodes in conjunction with treatment of the primary.55 A patient with a recurrent temple SCC in whom adjuvant RT was recommended in the setting of a positive deep margin should have the parotid nodes included electively en bloc in the RT field (Fig. 39-11).

Patients who develop metastatic cutaneous SCC to the parotid or neck are optimally treated with surgery and adjuvant RT with few exceptions.56 The aim of adjuvant RT is to reduce the risk of regional relapse because most patients have unfavorable features, such as multiple metastatic nodes, extranodal spread, close margins, or the presence of perineural invasion. Approximately 20% to 25% of patients do not have an obvious index lesion to explain the presence of metastatic nodes. With combined treatment, 5-year overall survival (OS) is 70% to 75%. Patients considered medically or technically inoperable can still be treated with RT alone, although the likelihood of cure is reduced.

Sentinel Node Biopsy

The role of sentinel node biopsy in NMSC is unclear because the overall incidence of metastatic nodal disease is low. In contrast to patients with melanoma, there is limited evidence to guide clinicians.57 In certain patients considered to have high-risk lesions, however, sentinel biopsy may be useful in guiding clinicians, provided that expertise in undertaking this investigation is available.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

With few exceptions, most studies report a marked benefit to locoregional control and survival with the addition of adjuvant RT. In the largest study (n = 1665) of its type, the addition of adjuvant RT significantly improved median survival in patients with lesions greater than 2 cm from 21 months to 50 months (p = .0003).58 In a meta-analysis of 1254 patients, Lewis and colleagues59 reported a significant reduction in local (hazard ratio 0.27, p <.001) and regional (hazard ratio 0.34, p <.001) relapse and a benefit in overall survival (hazard ratio 0.63, p = .04) in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant RT compared with patients treated surgery alone. Clark and colleagues60 analyzed data from two Australian Hospitals (Westmead and Royal Prince Alfred Hospitals, Sydney) and from Princess Margaret Hospital in Canada and documented significant improvement in local control (p = .009), regional control (p = .006), and disease-free survival (p = .013) from combined treatment versus surgery alone.

The routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy is unclear. In a phase II single arm study from Australia, 53 patients received concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy (carboplatin and etoposide) with RT with 3-year OS, locoregional control, and distant control rates of 76%, 75%, and 76%, respectively.61 These impressive results in patients with poor prognostic features, particularly the presence of nodal metastases in 33 (62%) patients, strongly suggest a potential benefit to the addition of combination chemotherapy in patients with unfavorable features. Another study compared patients treated with the addition of chemotherapy to RT (n = 40) with patients treated without chemotherapy (n = 62).62 The authors reported no significant OS benefit to patients receiving chemotherapy (p = .16) and no improvement in distant control (65% vs. 70%; p = .61). Although not excluding a possible benefit to chemotherapy, these results add support for a randomized controlled trial to confirm the hypothesis that chemotherapy would benefit these patients.

With few exceptions, most patients should proceed to wide-field adjuvant RT when a diagnosis has been confirmed. RT should not be delayed by the need for further surgery if excision margins are involved. Patients with small volume (<3 to 4 cm) nodal metastases can be treated adequately with RT without the need to undergo nodal resection. As a guide, treatment fields should encompass, as a minimum, the primary site, in-transit tissue, and first-echelon nodes (Fig. 39-12). Margins of at least 3 to 4 cm are recommended. In the setting of inoperable disease, definitive RT to doses of 50 to 55 Gy in 20 to 25 daily fractions still offers the likelihood of excellent in-field control (75%) and cure in a few patients.63

Locally Advanced Disease And Palliation

Patients with locally advanced (T4) primary skin cancers involving bone and cartilage, muscle, or nerves can still be treated and cured with definitive RT. In many cases, surgical salvage is an option if RT is unsuccessful. Al-Othman and colleagues64 documented an initial local control rate of 53% and an ultimate local control rate of 90% with surgical salvage in 85 patients with previously untreated (n = 43) and recurrent (n = 45) T4 skin carcinomas given RT to doses of 60 to 75 Gy over 6 to 8 weeks. Bone invasion or perineural spread was found to reduce the likelihood of local control in this small series. Cause-specific survival at 5 years was 76%, and 15% developed severe late complications in the form of soft tissue or bone and cartilage necrosis.

Many SCCs express epidermal growth factor receptor, and targeted treatment using monoclonal antibodies is emerging. In some cases, dramatic results have been obtained using this relatively nontoxic treatment.65

irradlation techniques

Carcinoma

Target Volume

In patients receiving postoperative irradiation in the setting of lymph node metastasis or perineural invasion, the initial portal also may need to encompass the primary tumor bed, if technically feasible. However, if the time interval from primary site treatment exceeds 12 months, and there is no evidence of local recurrence, this may be omitted. The clinical target volume in the setting of perineural invasion depends on the primary site and the relevant cranial nerves involved and in many cases includes the skull base and cavernous sinus.66 Electively treating regional lymph nodes in patients with perineural invasion is an option but probably unnecessary.

Setup, Field Arrangement, and Dose Fractionation Schedule

Patients are best immobilized in a position that gives optimal access to irradiate the tumor to ensure daily reproducibility. Preferably, the position is such that the plane of the skin to be treated is horizontal to facilitate the placement of a lead shield for skin collimation. Irradiation is delivered through a single appositional field, in most cases using superficial orthovoltage energy photons (usually 75 to 300 kVp) or electrons (usually 6 to 9 MeV). Low-energy photons are preferable to using small field electrons when treating skin cancers. Lesions can be treated effectively with electrons, provided that clinicians are aware of certain aspects of using electrons (e.g., skin sparing, dose constriction).67

Several techniques and devices are helpful in minimizing radiation exposure to the surrounding normal tissues and obtaining the desired dose distribution. A 3- to 4-mm-thick lead cutout is used for field shaping, conforming to the geometry of the lesion by skin collimation (Fig. 39-14). The overall size of the cutout should be large enough so that the cone or collimator setting for electron beams is at least 4 × 4 cm in size for reliable dosimetry. Skin bolus or a scatter plate is used when treatment is given with electrons to ensure full surface dose. Additional shielding can be applied to protect tissues from “exit radiation.” An internal eye shield is inserted when treating an eyelid lesion with orthovoltage x-rays or electrons of 8 MeV or less (see Fig. 39-9, B). It is important to calibrate commercially available eye shields individually with respect to their electron-attenuating properties because transmission through these shields can be considerable, even for a nominal 6-MeV beam. Similarly, lead oral cavity shields are used to shield the mandible, teeth, and oral cavity when treating a lip cancer (Fig. 39-15).

Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Adnexal Carcinoma

Setup, Field Arrangement, and Dose Fractionation Schedule

The general principles of patient setup and portal arrangement are as outlined for BCC and SCC. As primary treatment, radiation is administered, preferably with electrons, in 2- to 2.5-Gy fractions to a cumulative dose of 45 to 55 Gy for elective irradiation, plus a boost dose of 10 Gy in 5 fractions to the gross disease. A cumulative dose of 60 to 66 Gy may be recommended for the treatment of bulky, inoperable primary tumors. Elderly patients of poor performance status who are unsuitable for an extended course of RT may still benefit from shorter palliative schedules, such as 25 Gy in 5 fractions (Fig. 39-16).

Diagnostic And Treatment Algorithms

Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

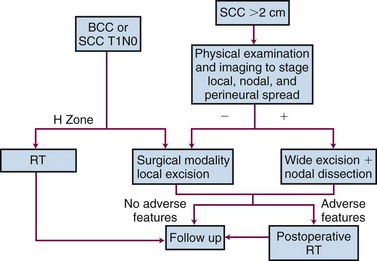

Figure 39-17 illustrates the diagnostic and treatment algorithm for BCC and SCC. The choice of treatment for individual patients is determined by factors such as the lesion site and size, anticipated functional and cosmetic results, treatment time, treatment cost, and patient preference. Surgical approaches are preferred for most patients with resectable tumors, but RT can yield better functional and cosmetic results for lesions of the nose, lower eyelids, and ears. A combination of surgery and adjuvant RT is indicated in larger tumors or tumors with perineural spread, invasion of bone, invasion of cartilage, extensive skeletal muscle infiltration, or nodal metastasis.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Adnexal Carcinoma

A combination of surgery (respecting form and function) and wide field elective or adjunctive irradiation is recommended for most patients with MCC and adnexal carcinoma. In most situations, there should be elective treatment, usually RT, of first echelon lymph nodes. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of MCC is unclear without supportive evidence to suggest an outcome benefit. RT alone for inoperable patients or patients refusing surgery still offers a potential cure. More recent evidence suggests that positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scanning in patients with MCC may alter management or prognosis or both in 30% to 40% of patients.68

2 Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:107-110.

3 Dasgupta T, Wilson LD, Yu JB. A retrospective review of 1349 cases of sebaceous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:158-165.

5 Otley C. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and skin cancer: a dangerous combination. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:231-236.

6 Stasko T, Brown MD, Carucci JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:642-650.

7 Hextall F, Leonardi-Bee J, Somchand N, et al: Interventions for the prevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in high-risk groups (Protocol). Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 3.

9 Hill L, Ferrini RL. Skin cancer prevention and screening: summary of the American College of Preventive Medicine’s practice policy statements. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:232-235.

11 Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2262-2269.

12 Marcil I, Stern R. Risk of developing a subsequent non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of a non-melanoma skin cancer: a critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1524-1528.

16 Geist DE, Garcia-Molner M, Fitzek MM, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma: raising awareness and optimizing management. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1642-1651.

18 Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs topical Tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

19 Moreno G, Chia ALK, Lim A, et al. Therapeutic options for Bowen’s disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:1-10.

20 Veness MJ. Treatment recommendations for patients diagnosed with high-risk cutaneous SCC. Australas Radiol. 2005;49:365-376.

21 Branstch KD, Meisner C, Schonfisch B, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:713-720.

22 Veness MJ, Palme CE, Morgan GJ. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results from 266 patients treated with metastatic nodal disease. Cancer. 2006;106:2389-2396.

23 Goh A, Howle J, Hughes M, et al. Managing patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the axilla or groin lymph nodes. Austral J Dermatol. 2010;51:113-117.

25 Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

28 Goedert JG. On behalf of The Rockville Merkel cell carcinoma group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4012-4026.

29 Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

30 Veness MJ, Palme CE, Morgan GJ. Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:170-174.

31 Veness MJ, Perera L, McCourt J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: improved outcome with the addition of adjuvant radiotherapy. Aust N Z J Surg. 2005;75:275-281.

32 Penn I, Roy FM. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

33 Rao NA, Hidayat AA, McLean IW, et al. Sebaceous carcinomas of the ocular adnexa: a clinicopathologic study of 104 cases, with five-year follow-up data. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:113-122.

34 Dowd M, Kumar RJ, Sharma R, et al. Diagnosis and management of sebaceous carcinoma: an Australian experience. Aust N Z J Surg. 2008;78:158-163.

35 Wick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT, et al. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin: II. extraocular sebaceous carcinomas. Cancer. 1985;56:1163-1172.

38 Fischer S, Breuninger H, Metzier G, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an often misdiagnosed, locally aggressive growing skin tumor. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:53-58.

39 Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:295-300.

40 Garcia-Serra A, Hinerman RW, Mendenhall WM, et al. Carcinoma of the ski with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 2003;25:1027-1033.

43 Esmaeli B, Ahmadi MA, Gillenwater AM, et al. The role of supraorbital nerve biopsy in cutaneous malignancies of the periocular region. Ophthalmol Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19:282-286.

45 Veness MJ. Time to rethink TNM staging in cutaneous SCC. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:702-703.

46 Palme CE, MacKay SG, Kalnins I, et al. The need for a better prognostic staging system in patients with metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15:103-106.

47 O’Brien CJ, McNeil EB, McMahon JD, et al. Significance of clinical stage, extent of surgery and pathological findings in metastatic cutaneous squamous carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2002;24:417-422.

48 Allen PJ, Browne WB, Jacques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

50 Swanson EL, Amdur RJ, Mendenhall WM, et al. Radiotherapy for basal cell carcinoma of the medial canthus. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2366-2368.

51 Veness MJ. The important role of radiotherapy in patients with non-melanoma skin cancer and other cutaneous entities. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:278-286.

52 Babington S, Veness MJ, Cakir B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip: does adjuvant radiotherapy improve local control following incomplete or inadequate excision? Aust N Z J Surg. 2003;73:621-625.

53 Petsuksiri J, Frank SJ, Garden AS, et al. Outcomes after radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Cancer. 2008;112:111-118.

54 Kwan W, Wilson D, Moravan V. Radiotherapy for locally advanced basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:406-411.

55 Martinez JC, Cook JL. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma without palpable lymphadenopathy: is there a therapeutic role for elective neck dissection? Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:410-420.

56 Veness MJ, Porceddu S, Palme CE, et al. Cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to parotid and cervical lymph nodes. Head Neck. 2007;29:621-631.

57 Sahn RE, Lang PG. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for high-risk nonmelanoma skin cancers. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:786-793.

58 Mojica P, Smith D, Ellenhorn JDI. Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol. 2007;27:1043-1047.

59 Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

60 Clark JR, Veness MJ, Gilbert R, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: is adjuvant radiotherapy necessary? Head Neck. 2007;29:249-257.

61 Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al. High risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

62 Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I, et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:114-119.

63 Veness M, Foote M, Gebski V, et al. The role of definitive radiotherapy alone in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: reporting the Australian experience of 43 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:703-709.

64 Al-Othman MOF, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ. Radiotherapy alone for clinical T4 skin carcinoma of the head and neck with surgery reserved for salvage. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:387-390.

65 Kim S, Eleff M, Nicolaou N. Cetuximab as primary treatment for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the neck. Head Neck. 2011;33:286-288.

66 Gluck I, Ibrahim M, Popovtzer A, et al. Skin cancer of the head and neck with perineural invasion: defining the clinical target volumes based on the pattern of failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:38-46.

68 Concannon R, Larcos G, Veness M. The impact of 18F-FDG PET-CT scanning for staging and management of Merkel cell carcinoma: results from Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:76-84.

1 Staples MP, Elwood M, Burton RC, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Australia: the 2002 national survey and trends since 1985. Med J Aust. 2006;184:6-10.

2 Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:107-110.

3 Dasgupta T, Wilson LD, Yu JB. A retrospective review of 1349 cases of sebaceous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:158-165.

4 Boukamp P. Non-melanoma skin cancer: what drives tumor development and progression? Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1657-1667.

5 Otley C. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and skin cancer: a dangerous combination. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:231-236.

6 Stasko T, Brown MD, Carucci JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:642-650.

7 Hextall F, Leonardi-Bee J, Somchand N, et al: Interventions for the prevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in high-risk groups (Protocol). Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 3.

8 Goldberg LH, Firoz BF, Weiss GJ, et al. Basal cell nevus syndrome: a brave new world. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:17-19.

9 Hill L, Ferrini RL. Skin cancer prevention and screening: summary of the American College of Preventive Medicine’s practice policy statements. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:232-235.

10 Raasch BA, Buettner PG, Garbe C. Basal cell carcinoma: histological classification and body-site distribution. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:401-407.

11 Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2262-2269.

12 Marcil I, Stern R. Risk of developing a subsequent non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of a non-melanoma skin cancer: a critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1524-1528.

13 Patterson JAK, Geronemus RG. Cancers of the skin. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1989:1469-1498.

14 Burdon-Jones D, Thomas PW. One-fifth of basal cell carcinoma have a morphoeic or partly morphoiec histology: implications for treatment. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:102-105.

15 McGuire JF, Ge NN, Dyson S. Nonmelanoma skin cancer of the head and neck (part 1): histopathology and clinical behavior. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30:121-133.

16 Geist DE, Garcia-Molner M, Fitzek MM, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma: raising awareness and optimizing management. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1642-1651.

17 Jefford M, Kiffer JD, Somers G, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: rapid symptomatic response to cisplatin and plaxitaxel. Aust N Z J Surg. 2004;74:704-705.

18 Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs topical Tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

19 Moreno G, Chia ALK, Lim A, et al. Therapeutic options for Bowen’s disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:1-10.

20 Veness MJ. Treatment recommendations for patients diagnosed with high-risk cutaneous SCC. Australas Radiol. 2005;49:365-376.

21 Branstch KD, Meisner C, Schonfisch B, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:713-720.

22 Veness MJ, Palme CE, Morgan GJ. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results from 266 patients treated with metastatic nodal disease. Cancer. 2006;106:2389-2396.

23 Goh A, Howle J, Hughes M, et al. Managing patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the axilla or groin lymph nodes. Austral J Dermatol. 2010;51:113-117.

24 Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

25 Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

26 Merkel F. Tastzellen und Tastkoerperchen bei den haushieren und beim menschen. Arch Mikr Anat. 1875;11:636-652.

27 Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer. 2008;113:2549-2558.

28 Goedert JG. On behalf of The Rockville Merkel cell carcinoma group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4012-4026.

29 Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

30 Veness MJ, Palme CE, Morgan GJ. Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:170-174.

31 Veness MJ, Perera L, McCourt J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: improved outcome with the addition of adjuvant radiotherapy. Aust N Z J Surg. 2005;75:275-281.

32 Penn I, Roy FM. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

33 Rao NA, Hidayat AA, McLean IW, et al. Sebaceous carcinomas of the ocular adnexa: a clinicopathologic study of 104 cases, with five-year follow-up data. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:113-122.

34 Dowd M, Kumar RJ, Sharma R, et al. Diagnosis and management of sebaceous carcinoma: an Australian experience. Aust N Z J Surg. 2008;78:158-163.

35 Wick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT, et al. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin: II. extraocular sebaceous carcinomas. Cancer. 1985;56:1163-1172.

36 Kampshoff JL, Cogbill TH. Unusual skin tumors: Merkel cell carcinoma, eccrine carcinoma, glomus tumors, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:727-738.

37 Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

38 Fischer S, Breuninger H, Metzier G, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an often misdiagnosed, locally aggressive growing skin tumor. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:53-58.

39 Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:295-300.

40 Garcia-Serra A, Hinerman RW, Mendenhall WM, et al. Carcinoma of the ski with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 2003;25:1027-1033.

41 Warner GC, Gandi M, Panizza B. Slowly progressive cranial nerve palsies. Med J Aust. 2006;184:641-643.

42 Galloway TJ, Morris CG, Mancuso AA, et al. Impact of radiographic findings on prognosis for skin cancer with clinical perineural invasion. Cancer. 2005;103:1254-1257.

43 Esmaeli B, Ahmadi MA, Gillenwater AM, et al. The role of supraorbital nerve biopsy in cutaneous malignancies of the periocular region. Ophthalmol Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19:282-286.

44 Talmi YP. Problems in the current TNM staging of nonmelanoma skin cancer of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2007;29:525-527.

45 Veness MJ. Time to rethink TNM staging in cutaneous SCC. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:702-703.

46 Palme CE, MacKay SG, Kalnins I, et al. The need for a better prognostic staging system in patients with metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15:103-106.

47 O’Brien CJ, McNeil EB, McMahon JD, et al. Significance of clinical stage, extent of surgery and pathological findings in metastatic cutaneous squamous carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2002;24:417-422.

48 Allen PJ, Browne WB, Jacques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

49 Huynh N, Veness MJ. Basal carcinoma of the lip treated with radiotherapy. Aust J Dermatol. 2002;43:15-19.

50 Swanson EL, Amdur RJ, Mendenhall WM, et al. Radiotherapy for basal cell carcinoma of the medial canthus. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2366-2368.

51 Veness MJ. The important role of radiotherapy in patients with non-melanoma skin cancer and other cutaneous entities. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:278-286.

52 Babington S, Veness MJ, Cakir B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip: does adjuvant radiotherapy improve local control following incomplete or inadequate excision? Aust N Z J Surg. 2003;73:621-625.

53 Petsuksiri J, Frank SJ, Garden AS, et al. Outcomes after radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Cancer. 2008;112:111-118.

54 Kwan W, Wilson D, Moravan V. Radiotherapy for locally advanced basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:406-411.

55 Martinez JC, Cook JL. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma without palpable lymphadenopathy: is there a therapeutic role for elective neck dissection? Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:410-420.

56 Veness MJ, Porceddu S, Palme CE, et al. Cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to parotid and cervical lymph nodes. Head Neck. 2007;29:621-631.

57 Sahn RE, Lang PG. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for high-risk nonmelanoma skin cancers. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:786-793.

58 Mojica P, Smith D, Ellenhorn JDI. Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol. 2007;27:1043-1047.

59 Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

60 Clark JR, Veness MJ, Gilbert R, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: is adjuvant radiotherapy necessary? Head Neck. 2007;29:249-257.

61 Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al. High risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

62 Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I, et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:114-119.

63 Veness M, Foote M, Gebski V, et al. The role of definitive radiotherapy alone in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: reporting the Australian experience of 43 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:703-709.

64 Al-Othman MOF, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ. Radiotherapy alone for clinical T4 skin carcinoma of the head and neck with surgery reserved for salvage. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:387-390.

65 Kim S, Eleff M, Nicolaou N. Cetuximab as primary treatment for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the neck. Head Neck. 2011;33:286-288.

66 Gluck I, Ibrahim M, Popovtzer A, et al. Skin cancer of the head and neck with perineural invasion: defining the clinical target volumes based on the pattern of failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:38-46.

67 Zablow AI, Eanelli TR, Sanfilippo LJ. Electron beam therapy for skin cancer of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1992;14:188-195.

68 Concannon R, Larcos G, Veness M. The impact of 18F-FDG PET-CT scanning for staging and management of Merkel cell carcinoma: results from Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:76-84.