Chapter 657 Cutaneous Bacterial Infections

657.1 Impetigo

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Bullous impetigo is always caused by S. aureus strains that produce exfoliative toxins. The staphylococcal exfoliative toxins (ETA, ETB, ETD) blister the superficial epidermis by hydrolyzing human desmoglein 1, resulting in a subcorneal vesicle. This is also the target antigen of the autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus (Chapters 174 and 176).

Clinical Manifestations

Nonbullous Impetigo

Nonbullous impetigo accounts for > 70% of cases. Lesions typically begin on the skin of the face or on extremities that have been traumatized. The most common lesions that precede nonbullous impetigo are insect bites, abrasions, lacerations, chickenpox, scabies pediculosis, and burns. A tiny vesicle or pustule forms initially and rapidly develops into a honey-colored crusted plaque that is generally <2 cm in diameter (Fig. 657-1). The infection may be spread to other parts of the body by the fingers, clothing, and towels. Lesions are associated with little to no pain or surrounding erythema, and constitutional symptoms are generally absent. Pruritus occurs occasionally, regional adenopathy is found in up to 90% of cases, and leukocytosis is present in about 50%.

Complications

Infection with nephritogenic strains of GABHS may result in acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (Chapter 505.1). The clinical character of impetigo lesions is not predictive of the development of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. The most commonly affected age group is school-aged children, 3-7 yr old. The latent period from onset of impetigo to development of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis averages 18-21 days, which is longer than the 10-day latency period after pharyngitis. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis occurs epidemically after either pharyngeal or skin infection. Impetigo-associated epidemics have been caused by M groups 2, 49, 53, 55, 56, 57, and 60. Strains of GABHS that are associated with endemic impetigo in the USA have little or no nephritogenic potential. Acute rheumatic fever does not occur as a result of impetigo.

Bernard P. Management of common bacterial infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:122-128.

Chen AE, Carroll KC, Diener-West M. Randomized controlled trial of cephalexin versus clindamycin for uncomplicated pediatric skin infections. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e573-e580.

Parish LC, Parish JL. Retapamulin: a new topical antibiotic for the treatment of uncomplicated skin infections. Drugs Today. 2008;44:91-102.

Schachner LA. Treatment of uncomplicated skin infections in the pediatric and adolescent patient populations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:s30-s33.

657.2 Subcutaneous Tissue Infections

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Etiology

The rest of the cases and the most fulminant infections, associated with toxic shock syndrome and a high case fatality rate, are usually caused by S. pyogenes (Chapter 176). Streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis may occur in the absence of toxic shock–like syndrome and is potentially fatal and associated with substantial morbidity. Necrotizing fasciitis can occasionally be caused by S. aureus; Clostridium perfringens; Clostridium septicum; P. aeruginosa; Vibrio spp., particularly Vibrio vulnificus; and fungi of the order Mucorales, particularly Rhizopus spp., Mucor spp., and Absidia spp. Necrotizing fasciitis has also been reported on rare occasions to result from non–group A streptococci such as group B, C, F, or G streptococci, S. pneumoniae, or H. influenzae type b.

Kroshinsky D, Grossman ME, Fox LP. Approach to the patient with presumed cellulites. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:168-178.

Lio PA. The many faces of cellulitis. Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed. 2009;94:50-54.

Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279-288.

657.3 Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (Ritter Disease)

Clinical Manifestations

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, which occurs predominantly in infants and children younger than 5 yr, includes a range of disease from localized bullous impetigo to generalized cutaneous involvement with systemic illness. Onset of the rash may be preceded by malaise, fever, irritability, and exquisite tenderness of the skin. Scarlatiniform erythema develops diffusely and is accentuated in flexural and periorificial areas. The conjunctivae are inflamed and occasionally become purulent. The brightly erythematous skin may rapidly acquire a wrinkled appearance, and in severe cases, sterile, flaccid blisters and erosions develop diffusely. Circumoral erythema is characteristically prominent, as is radial crusting and fissuring around the eyes, mouth, and nose. At this stage, areas of epidermis may separate in response to gentle shear force (Nikolsky sign) (Fig. 657-2). As large sheets of epidermis peel away, moist, glistening, denuded areas become apparent, initially in the flexures and subsequently over much of the body surface (Fig. 657-3). This development may lead to secondary cutaneous infection, sepsis, and fluid and electrolyte disturbances. The desquamative phase begins after 2-5 days of cutaneous erythema; healing occurs without scarring in 10-14 days. Patients may have pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, and superficial erosions of the lips, but intraoral mucosal surfaces are spared. Although some patients appear ill, many are reasonably comfortable except for the marked skin tenderness.

657.4 Ecthyma

See also Chapters 182 and 202.

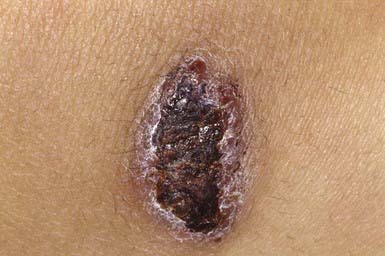

Ecthyma resembles nonbullous impetigo in onset and appearance but gradually evolves into a deeper, more chronic infection. The initial lesion is a vesicle or vesicular pustule with an erythematous base that erodes through the epidermis into the dermis to form an ulcer with elevated margins. The ulcer becomes obscured by a dry, heaped-up, tightly adherent crust (Fig. 657-4) that contributes to the persistence of the infection and scar formation. Lesions may be spread by autoinoculation, may be as large as 4 cm, and occur most frequently on the legs. Predisposing factors include the presence of pruritic lesions, such as insect bites, scabies, or pediculosis, that are subject to frequent scratching; poor hygiene; and malnutrition. Complications include lymphangitis, cellulitis, and, rarely, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. The causative agent is usually GABHS; S. aureus is also cultured from most lesions but is probably a secondary pathogen. Crusts should be softened with warm compresses and removed. Systemic antibiotic therapy, as for impetigo, is indicated; almost all lesions are responsive to treatment with penicillin.

657.5 Other Cutaneous Bacterial Infections

Blastomycosis-Like Pyoderma (Pyoderma Vegetans)

Blastomycosis-like pyoderma is an exuberant cutaneous reaction to bacterial infection that occurs primarily in children who are malnourished and immunosuppressed. The organisms most commonly isolated from lesions are S. aureus and group A streptococcus, but several other organisms have been associated with these lesions, including P. aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, diphtheroids, Bacillus spp., and C. perfringens. Crusted, hyperplastic plaques on the extremities are characteristic, sometimes forming from the coalescence of many pinpoint, purulent, crusted abscesses (Fig. 657-5). Ulceration and sinus tract formation may develop, and additional lesions may appear at sites distant from the site of inoculation. Regional lymphadenopathy is common, but fever is not. Histopathologic examination reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and abscesses composed of neutrophils and/or eosinophils. Giant cells are usually lacking. The differential diagnosis includes deep fungal infection, particularly blastomycosis (Fig 657-6) and tuberculous and atypical mycobacterial infection. Underlying immunodeficiency should be ruled out, and the selection of antibiotics should be guided by susceptibility testing because the response to antibiotics is often poor.

Blistering Distal Dactylitis

Blistering distal dactylitis is a superficial blistering infection of the volar fat pad on the distal portion of the finger or thumb (Fig. 657-7). More than one finger may be involved, as may the volar surfaces of the proximal phalanges, palms, and toes. Blisters are filled with a watery purulent fluid that contains polymorphonuclear leukocytes and, usually, chains of gram-positive cocci. Patients commonly have no preceding history of trauma, and systemic symptoms are generally absent. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis has not occurred after blistering distal dactylitis. The infection is caused most commonly by group A streptococcus but has also occurred as a result of infection with S. aureus. If left untreated, blisters may continue to enlarge and extend to the paronychial area. The infection responds to incision and drainage and a 10-day course of systemic cephalosporin therapy.

Perianal Infectious Dermatitis

Perianal infectious dermatitis presents most commonly in boys (70% of cases) between the ages of 6 mo and 10 yr as perianal dermatitis (90% of cases) and pruritus (80% of cases) (Fig 657-8). The incidence of perianal infectious dermatitis is not known precisely but ranges from 1/2,000 to 1/218 patient visits. The rash is superficial, erythematous, well marginated, nonindurated, and confluent from the anus outward. Acutely (<6 wk), the rash tends to be bright red, moist, and tender to touch. At this stage, a white pseudomembrane may be present. As the rash becomes more chronic, the perianal eruption may consist of painful fissures, a dried mucoid discharge, or psoriasiform plaques with yellow peripheral crust. In girls, the perianal rash may be associated with vulvovaginitis. In boys, the penis may be involved. Approximately 50% of patients have rectal pain, most commonly described as burning inside the anus during defecation, and 33% have blood-streaked stools. Fecal retention is a frequent behavioral response to the infection. Patients also have presented with guttate psoriasis. Although local induration or edema may occur, constitutional symptoms such as fever, headache, and malaise are absent, suggesting that subcutaneous involvement, as in cellulitis, is absent. Familial spread of perianal infectious dermatitis is common, particularly when family members bathe together or use the same water.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis, or superficial infection of the hair follicle, is most often caused by S. aureus (Bockhart impetigo). The lesions are typically small, discrete, dome-shaped pustules with an erythematous base, located at the ostium of the pilosebaceous canals (Fig. 657-9). Hair growth is unimpaired, and the lesions heal without scarring. Favored sites include the scalp, buttocks, and extremities. Poor hygiene, maceration, drainage from wounds and abscesses, and shaving of the legs can be provocative factors. Folliculitis can also occur as a result of tar therapy or occlusive wraps. The moist environment encourages bacterial proliferation. In HIV-infected patients, S. aureus may produce confluent erythematous patches with satellite pustules in intertriginous areas and violaceous plaques composed of superficial follicular pustules in the scalp, axillae, or groin. The differential diagnosis include Candida, which may cause satellite follicular papules and pustules surrounding erythematous patches of intertrigo, and Malassezia furfur, which produces 2- to 3-mm, pruritic, erythematous, perifollicular papules and pustules on the back, chest, and extremities, particularly in patients who have diabetes mellitus or are taking corticosteroids or antibiotics. Diagnosis is made by examining potassium hydroxide–treated scrapings from lesions. Detection of Malassezia may require a skin biopsy, demonstrating clusters of yeast and short, branching hyphae (“macaroni and meatballs”) in widened follicular ostia mixed with keratinous debris.

Hot tub folliculitis is attributable to P. aeruginosa, predominantly serotype O-11. The lesions are pruritic papules and pustules or deeply erythematous to violaceous nodules that develop 8-48 hr after exposure and are most dense in areas covered by a bathing suit (Fig. 657-10). Patients occasionally experience fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. The organism is readily cultured from pus. The eruption usually resolves spontaneously in 1-2 wk, often leaving postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Consideration should be given to use of systemic antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) in adolescent patients with constitutional symptoms. Immunocompromised children are susceptible to complications of Pseudomonas folliculitis (cellulitis) and should avoid hot tubs.

Furuncles and Carbuncles

Clinical Manifestations

This follicular lesion may originate from a preceding folliculitis or may arise initially as a deep-seated, tender, erythematous, perifollicular nodule. Although lesions are initially indurated, central necrosis and suppuration follow, leading to rupture and discharge of a central core of necrotic tissue and destruction of the follicle (Fig. 657-11). Healing occurs with scar formation. Sites of predilection are the hair-bearing areas on the face, neck, axillae, buttocks, and groin. Pain may be intense if the lesion is situated in an area where the skin is relatively fixed, such as in the external auditory canal or over the nasal cartilages. Patients with furuncles usually have no constitutional symptoms; bacteremia may occasionally ensue. Rarely, lesions on the upper lip or cheek may lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis. Infection of a group of contiguous follicles, with multiple drainage points, accompanied by inflammatory changes in surrounding connective tissue is a carbuncle. Carbuncles may be accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and bacteremia.

Pitted Keratolysis

Pitted keratolysis occurs most frequently in humid tropical and subtropical climates, particularly in individuals whose feet are moist for prolonged periods, for example, as a result of hyperhidrosis, prolonged wearing of boots, or immersion in water. It occurs most commonly in young males from early adolescence to the late 20s. The lesions consist of 1- to 7-mm, irregularly shaped, superficial erosions of the horny layer on the soles, particularly at weight-bearing sites (Fig. 657-12). Brownish discoloration of involved areas may be apparent. A rare variant manifests as thinned, erythematous to violaceous plaques in addition to the typical pitted lesions. The condition is frequently malodorous, and is painful in about 50% of cases. The most likely etiologic agent is a species of Corynebacterium. Dermatophilus congolensis and Kytococcus sedentarius have also been isolated from lesions. Treatment of hyperhidrosis is mandatory. Avoidance of moisture and maceration produces slow, spontaneous resolution of the infection. Topical or systemic erythromycin and topical imidazole creams are standard therapy.

Tuberculosis of the Skin (Chapters 207 and 209)

Primary cutaneous tuberculosis (tuberculous chancre) results when M. tuberculosis or M. bovis gains access to the skin or mucous membranes through trauma. Sites of predilection are the face, lower extremities, and genitals. The initial lesion develops 2-4 wk after introduction of the organism into the damaged tissue. A red-brown papule gradually enlarges to form a shallow, firm, sharply demarcated ulcer. Satellite abscesses may be present. Some lesions acquire a crust resembling impetigo, and others become heaped up and verrucous at the margins. The primary lesion can also manifest as a painless ulcer on the conjunctiva, gingiva, or palate and occasionally as a painless acute paronychia. Painless regional adenopathy may appear several weeks after the development of the primary lesion and may be accompanied by lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, or perforation of the skin surface, forming scrofuloderma. Untreated lesions heal with scarring within 12 mo but may reactivate, may form lupus vulgaris, or, rarely, may progress to the acute miliary form. Therefore, antituberculous therapy is indicated (Chapter 207).

Scrofuloderma results from enlargement, cold abscess formation, and breakdown of a lymph node, most frequently in a cervical chain, with extension to the overlying skin. Linear or serpiginous ulcers and dissecting fistulas and subcutaneous tracts studded with soft nodules may develop. Spontaneous healing may take years, eventuating in cordlike keloid scars. Lupus vulgaris may also develop. Scrofuloderma of a cervical lymph node often originates in the larynx and was linked in the past to ingestion of milk containing M. bovis. Lesions may also originate from an underlying infected joint, tendon, bone, or epididymis. The differential diagnosis includes syphilitic gumma, deep fungal infections, actinomycosis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. The course is indolent, and constitutional symptoms are typically absent. Antituberculous therapy is indicated (Chapter 207).

Atypical mycobacterial infection may cause cutaneous lesions in children. Mycobacterium marinum is found in saltwater, freshwater, and diseased fish. In the USA, it is most commonly acquired from tropical fish tanks and swimming pools. Traumatic abrasion of the skin serves as a portal of entry for the organism. Approximately 3 wk after inoculation, a single reddish papule develops and enlarges slowly to form a violaceous nodule or, occasionally, a warty plaque (Fig. 657-13). The lesion occasionally breaks down to form a crusted ulcer or a suppurating abscess. Sporotrichoid erythematous nodules along lymphatics may also suppurate and drain. Lesions are most common on the elbows, knees, and feet of swimmers and on the hands and fingers in persons with aquarium-acquired infection. Systemic signs and symptoms are absent. Regional lymph nodes occasionally become slightly enlarged but do not break down. Rarely, the infection becomes disseminated, particularly in an immunosuppressed host. A biopsy specimen of a fully developed lesion demonstrates a granulomatous infiltrate with tuberculoid architecture. Treatment options include tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, clarithromycin, and rifampin plus ethambutol. Application of heat to the affected site may be a useful adjunctive therapy (Chapter 209).

M. scrofulaceum causes cervical lymphadenitis (scrofuloderma) in young children, typically in the submandibular region. Nodes enlarge over several weeks, ulcerate, and drain. The local reaction is nontender and circumscribed, constitutional symptoms are absent, and there generally is no evidence of lung or other organ involvement. Other atypical mycobacteria may cause a similar presentation, including Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium kansasii, and Mycobacterium fortuitum. Treatment is accomplished by excision and administration of antituberculous drugs (Chapter 209).

M. avium complex, composed of >20 subtypes, most commonly causes chronic pulmonary infection. Cervical lymphadenitis and osteomyelitis occur occasionally, and papules or purulent leg ulcers occur rarely by primary inoculation. Skin lesions may be an early sign of disseminated infection. The lesions may take various forms, including erythematous papules, pustules, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, panniculitis, and sporotrichoid spread along lymphatics. For treatment, see Chapter 209.

Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73.

Blaise G, Nikkels AF, Hermanns-Le T, et al. Corynebacterium-associated skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:884-890.

Handog EB, Gabriel TG, Pineda RT. Management of cutaneous tuberculosis. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:154-161.

Meury SN, Erb T, Schaad UB, et al. Randomized, comparative efficacy trial of oral penicillin versus cefuroxime for perianal streptococcal dermatitis. J Pediatr. 2008;153:799-802.

Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978.

Sawalka SS, Phiske MM, Jerajanji HR. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:117-119.

Scheinfeld NS. Is blistering distal dactylitis a variant of bullous impetigo? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:314-316.

Walsh DS, Portaels F, Meyers WM. Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:969-978.

Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.