Cushing syndrome

1. Describe the normal function of cortisol in healthy people.

Cortisol and other glucocorticoids have many effects as physiologic regulators. They increase glucose production and protein breakdown, inhibit protein synthesis, stimulate lipolysis, and affect immunologic and inflammatory responses. Glucocorticoids are important for the maintenance of blood pressure and form an essential part of the body’s response to stress.

2. How are cortisol levels normally regulated?

Adrenal production of cortisol is stimulated by the pituitary hormone adrenocorticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]). ACTH production is stimulated by the hypothalamic hormones corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone [ADH]). Cortisol feeds back to the pituitary and hypothalamus to suppress levels of ACTH and CRH. Under nonstress conditions, cortisol is secreted in a pronounced circadian rhythm, with higher levels early in the morning and lower levels late in the evening. Under stressful conditions, secretion of CRH, ACTH, and cortisol increases, and the circadian variation is blunted. Because of the wide variation in cortisol levels over 24 hours and appropriate elevations during stressful conditions, it may be difficult to distinguish normal secretion from abnormal secretion. For this reason, the evaluation of a patient with suspected Cushing’s disease is often complex and confusing.

3. What are the clinical symptoms of excessive levels of cortisol?

Prolonged and inappropriately high cortisol levels lead to Cushing syndrome, characterized by:

Obesity, especially central (truncal) obesity, with wasting of the extremities, moon facies, supraclavicular fat pads, and buffalo hump

Obesity, especially central (truncal) obesity, with wasting of the extremities, moon facies, supraclavicular fat pads, and buffalo hump

Thinning of the skin, with facial plethora, easy bruising, and violaceous striae

Thinning of the skin, with facial plethora, easy bruising, and violaceous striae

Muscular weakness, especially proximal muscle weakness, and atrophy

Muscular weakness, especially proximal muscle weakness, and atrophy

Hypertension, atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, and edema

Hypertension, atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, and edema

Gonadal dysfunction and menstrual irregularities

Gonadal dysfunction and menstrual irregularities

Psychologic disturbances (e.g., depression, emotional lability, irritability, sleep disturbances)

Psychologic disturbances (e.g., depression, emotional lability, irritability, sleep disturbances)

4. All of my clinic patients look like they have Cushing syndrome. Are some clinical findings more specific for Cushing syndrome than others?

Some manifestations of Cushing syndrome are common but nonspecific, whereas others are less common but quite specific. These two groups of clinical findings are listed in Table 23-1.

TABLE 23-1.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS OF CUSHING SYNDROME

| More specific, less common | Easy bruising, thin skin (in young patient) |

| Facial plethora | |

| Violaceous striae | |

| Proximal muscle weakness | |

| Hypokalemia | |

| Osteoporosis (in young patient) | |

| More common, less specific | Hypertension |

| Obesity/weight gain | |

| Abnormal glucose tolerance or diabetes mellitus | |

| Depression, irritability | |

| Peripheral edema | |

| Acne, hirsutism | |

| Decreased libido, menstrual irregularities |

5. A patient presents with a history of obesity, hypertension, irregular menses, and depression. Does she have excessive production of cortisol?

Excessive cortisol is highly unlikely. Although the listed findings are consistent with glucocorticoid excess, they are nonspecific; most patients with such findings do not have Cushing syndrome (see Table 23-1). True Cushing syndrome is uncommon, with an incidence of 2 to 3 cases per million people per year, although it may be higher in patients with hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, or incidental adrenal masses.

6. The patient also complains of excessive hair growth and has increased terminal hair on the chin, along the upper lip, and on the upper back. Is this finding relevant?

Hirsutism is a common, nonspecific finding in many female patients. However, it is also consistent with Cushing syndrome. If it is due to Cushing syndrome, hirsutism is caused by excessive production of adrenal androgens under ACTH stimulation. Thus hirsutism in a patient with Cushing syndrome is a clue that the disorder is due to excessive production of ACTH. (The only other condition associated with excessive production of glucocorticoids and androgens is adrenal cancer, which is usually obvious on presentation.)

7. The patient also has increased pigmentation of the areolae, palmar creases, and an old surgical scar. Are these findings relevant?

Hyperpigmentation is a sign of elevated production of ACTH and related peptides by the pituitary gland. It is uncommon (but possible) in Cushing syndrome due to benign pituitary tumors, because ACTH levels do not usually rise high enough to cause hyperpigmentation. It is more common in the ectopic ACTH syndrome, because ectopic tumors produce more ACTH and other peptides. The combination of Cushing syndrome and hyperpigmentation may be bad news.

8. What is the cause of death in patients with Cushing syndrome?

Patients with inadequately treated Cushing syndrome have a markedly increased mortality rate (four-to fivefold above the normal rate), usually from cardiovascular disease or infections. Hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, and visceral obesity all contribute to the excess risk for cardiovascular mortality. This excess mortality normalizes with adequate therapy.

9. What causes Cushing syndrome?

Cushing syndrome is a nonspecific name for any source of excessive glucocorticoids. There are four main causes, which are further detailed in Table 23-2:

TABLE 23-2.

CAUSES OF CUSHING SYNDROME AND THEIR RELATIVE FREQUENCY

| ACTH-dependent (80%) | Pituitary (85%): |

| Corticotroph adenoma | |

| Corticotroph hyperplasia (rare) | |

| Ectopic ACTH syndrome (15%): | |

| Oat-cell carcinoma (50%) | |

| Foregut tumors (35%) | |

| Bronchial carcinoid | |

| Thymic carcinoid | |

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma | |

| Islet-cell tumors | |

| Pheochromocytoma | |

| Other tumors (10%) | |

| Ectopic CRH (>1%) | |

| ACTH-independent (20%) | Adrenal tumors: |

| Adrenal adenoma (>50%) | |

| Adrenal adenoma (>50%) | |

| Micronodular hyperplasia (rare) | |

| Macronodular hyperplasia (rare) | |

| Exogenous glucocorticoids (common): | |

| Therapeutic (common) | |

| Factitious (rare) |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropin; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone.

10. Of the various types of Cushing syndrome, which is the most common?

Overall, exogenous Cushing syndrome is most common. It rarely presents a diagnostic dilemma, because the physician usually knows that the patient is receiving glucocorticoids. Of the endogenous causes of Cushing syndrome, pituitary Cushing’s disease accounts for about 70% of cases. Ectopic ACTH secretion and adrenal tumors cause approximately 15% of cases each (see Table 23-2 for frequencies).

11. Do age and gender matter in the differential diagnosis of Cushing syndrome?

Of patients with Cushing’s disease (pituitary tumors), 80% are women, whereas the ectopic ACTH syndrome is more common in men. Therefore, in a male patient with Cushing syndrome, the risk of an extrapituitary tumor is higher. The age range in Cushing’s disease is most frequently 20 to 40 years, whereas ectopic ACTH syndrome has a peak incidence at 40 to 60 years. Therefore, the risk of an extrapituitary tumor in an older patient with Cushing syndrome is increased. Children with Cushing syndrome have a higher risk of malignant adrenal tumors.

12. The patient with obesity, hypertension, irregular menses, depression, and hirsutism looks like she may have Cushing syndrome. What should I do?

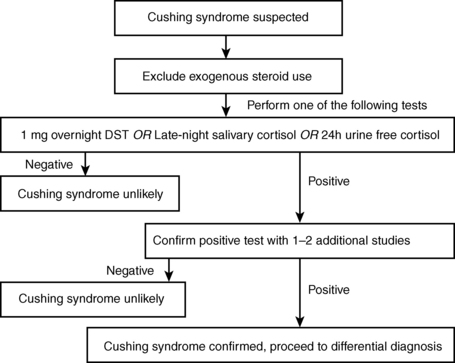

There are three widely used screening tests for Cushing syndrome that have comparable sensitivities and specificities, and each can be used in the initial evaluation of a patient with suspected Cushing syndrome (Fig. 23-1); they are as follows:

Figure 23-1. Diagnosis of Cushing syndrome.

1. The overnight low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. The patient takes 1 mg of dexamethasone at 11 pm, and the serum cortisol level is measured at 8:00 the next morning. In healthy unstressed subjects, dexamethasone (a potent glucocorticoid that does not cross-react with the cortisol assay) suppresses production of CRH, ACTH, and cortisol. In contrast, patients with endogenous Cushing syndrome should not suppress cortisol production (serum cortisol remains > 1.8 μg/dL) when given 1 mg of dexamethasone.

2. Measurement of cortisol in saliva samples collected on two separate evenings between 11 pm and midnight. Salivary cortisol levels are low in nonstressed subjects late at night but are high in patients with Cushing syndrome because of loss of the normal diurnal rhythm in cortisol production.

3. Urine free cortisol (UFC) levels, measured in a 24-hour collection of urine. UFC is elevated in most patients with Cushing syndrome, but only a value fourfold above the normal range is diagnostic of Cushing syndrome, as more mild elevations can be seen in stress or illness.

13. The patient underwent a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. The morning cortisol level is 7 μg/dL. Does she have Cushing syndrome?

Probably not. Acute or chronic illnesses, depression, and alcohol abuse activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis because of stress and make the patient resistant to dexamethasone suppression. In fact, because Cushing syndrome is so rare, a nonsuppressed cortisol level after dexamethasone is more likely to be a false-positive result, rather than truly indicating the presence of Cushing syndrome. Similar limitations exist for the other two screening tests. Further evaluation is best conducted by an endocrinologist and may include performing the alternate screening tests to see if their results are concordant, as well as additional biochemical tests (see Fig. 23-1).

14. Further biochemical testing confirms that the patient has Cushing syndrome. What should I do next?

After you have made the biochemical diagnosis of Cushing syndrome, the next step is to determine whether she has ACTH-dependent or ACTH-independent disease. This distinction is made by measuring plasma levels of ACTH. Measurements should be repeated a number of times because secretion of ACTH is variable.

15. The patient’s ACTH level is “normal.” Was the original suspicion of Cushing syndrome incorrect?

No. A normal or slightly elevated ACTH value is the usual finding in ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas. More marked elevations of ACTH suggest ectopic secretion of ACTH, although small carcinoid tumors also have normal or mildly elevated ACTH values. Suppressed ACTH levels (< 10 pg/mL), in contrast, suggest an adrenal tumor. If ACTH levels are indeterminate, measurements of ACTH during stimulation with CRH can be helpful.

16. After the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome, what is the next step?

Because the most common site of excessive secretion of ACTH is a pituitary tumor, radiologic imaging of the pituitary gland is the next step. The best study is high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary gland.

17. The pituitary MRI findings in the patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome are normal. Is the next step a search for a carcinoid tumor, under the assumption that the pituitary is not the source of excessive ACTH?

Not so fast. At least half of pituitary MRI results are negative in proven pituitary-dependent Cushing syndrome because most corticotroph adenomas are tiny and may not be visible on MRI.

18. The pituitary MRI shows a 3-mm hypodense area in the lateral aspect of the pituitary gland. Is it time to call the neurosurgeon?

Again, not so fast. This finding is nonspecific and occurs in up to 10% of healthy people. It may or may not be related to Cushing syndrome. The odds are good that the patient has a pituitary tumor, but the MRI findings do not prove this. The MRI is diagnostic only if it shows a large tumor.

One option is to proceed directly to pituitary surgery because a patient with abnormal MRI findings has a 90% chance of having an ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor. To achieve more diagnostic certainty, one has to perform bilateral simultaneous inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) for ACTH levels. Catheters are advanced through the femoral veins into the inferior petrosal sinuses, which drain the pituitary gland, and blood samples are obtained for ACTH levels. If ACTH levels in the petrosal sinuses are significantly higher than those in peripheral samples, the pituitary gland is the source of excessive ACTH. If there is no gradient between petrosal sinus and peripheral levels of ACTH, the patient probably has a carcinoid tumor somewhere. The accuracy of the test is further increased if ACTH responses to injection of exogenous CRH are measured. Bilateral IPSS should be performed by experienced radiologists at referral centers.

20. IPSS shows no gradient in ACTH levels. Now what?

Start the search for a carcinoid tumor. Because the most likely location is the lung, computed tomography (CT) of the lungs should be ordered. If the results are negative, CT of the abdomen should be ordered because carcinoids also occur in the pancreas, intestinal tract, and adrenal glands.

21. IPSS shows a marked central-to-peripheral gradient in ACTH levels. Now what?

Transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) should be scheduled with an experienced neurosurgeon who is comfortable examining the pituitary for small adenomas. ACTH levels from the right and left petrosal sinuses obtained during the sampling study may tell the neurosurgeon in which side of the pituitary gland the tumor is likely to be found, but this information is not 100% accurate.

22. What if surgery is unsuccessful?

If TSS does not cure a patient with Cushing’s disease, alternative therapies must be tried because patients with inadequately treated hypercortisolism have increased morbidity and mortality rates. Of the various options after failed surgery, none is ideal. Patients may require repeat pituitary surgery, radiation therapy, medical therapy to block cortisol secretion, bilateral adrenalectomy, or a combination of these. Medical therapy may include ketoconazole, metyrapone, mitotane, or etomidate, all of which directly suppress adrenal cortisol production. Also available are centrally acting agents that suppress ACTH secretion, and mifepristone, which blocks glucocorticoid action at its receptor. These decisions should be made by an experienced endocrinologist.

23. Why not just take out the patient’s adrenal glands?

Bilateral adrenalectomy can be safely performed via a laparoscopic approach, with low morbidity in experienced hands. However, this procedure leads to lifelong adrenal insufficiency and dependence on exogenous glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. The other main drawback is the development of Nelson syndrome in up to 30% of patients after adrenalectomy. Nelson syndrome is the appearance, sometimes years after adrenalectomy, of an aggressive corticotroph pituitary tumor.

24. What are the correct diagnostic and treatment options for patients with ACTH-independent (adrenal) Cushing syndrome?

Such patients usually have either an adrenal adenoma or carcinoma, so an adrenal CT scan should be ordered. A mass is usually present, and surgery should be planned. If the mass is obviously cancer, surgery may still help in debulking the tumor and improving the metabolic consequences of hypercortisolemia. If there are multiple adrenal nodules, the patient may have a rare form of Cushing syndrome and should be evaluated by an endocrinologist. As a caveat, there is also a high prevalence of incidental, nonfunctioning adrenal adenomas in the general population (up to 5%), and the CT findings may not be conclusive.

25. What happens to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis after a patient undergoes successful removal of an ACTH-secreting pituitary adenoma or a cortisol-secreting adrenal adenoma?

The axis is suppressed, and clinical adrenal insufficiency develops, unless the patient is given gradually decreasing doses of exogenous glucocorticoids for a time after surgery.

26. What would be the most likely diagnosis if the original patient had all the signs of Cushing syndrome but low urinary and serum levels of cortisol?

The most likely scenario would be that the patient is surreptitiously or accidentally ingesting a glucocorticoid that gives all the findings of glucocorticoid excess but is not measured in the cortisol assay. The patient and family members should be questioned about possible access to medications, and special assays can measure the various synthetic glucocorticoids.

27. Do tumors ever cause Cushing syndrome by making excessive CRH?

Yes. Occasionally patients who undergo TSS for a presumed corticotroph adenoma have corticotroph hyperplasia instead. At least some of these cases are secondary to ectopic production of CRH from a carcinoid tumor in the lung, abdomen, or other location. Therefore serum levels of CRH should be measured in patients with Cushing syndrome and corticotroph hyperplasia. If the levels are elevated, a careful search should be performed for possible ectopic sources of CRH.

Boscaro, M, Arnaldi, G. Approach to the patient with possible Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3121–3131.

Carroll, TB, Findling, JW. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11:147–153.

Nieman, LK, Biller, BMK, Findling, JW, et al, The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1526–1540.

Sharma, ST, Neiman, LK, Cushing’s syndrome. all variants detection, and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2011;40:379–391.

Tritos, NA. Advances in medical therapies for Cushing’s syndrome. Discover Med. 2012;13:171–179.