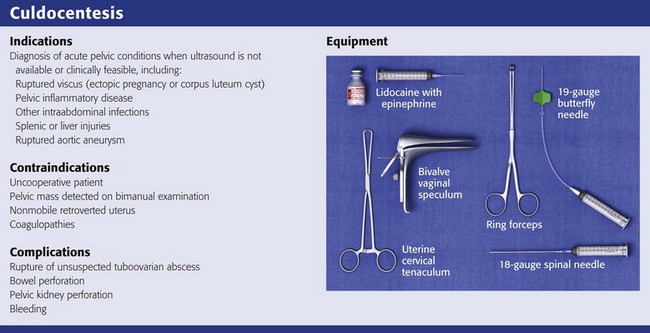

Culdocentesis

Culdocentesis is a procedure in which a hollow needle is inserted through the posterior vaginal wall into the peritoneal space to obtain peritoneal fluid for analysis and culture. This procedure is simple, rapid, and safe. The technique is used primarily to diagnose ruptured ectopic pregnancies and ruptured ovarian cysts and, rarely, to obtain material for culture to aid in the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). The availability of bedside ultrasound, high-resolution transvaginal ultrasound, and highly sensitive β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) assays has led to a decline in the use of this procedure. Despite this change, culdocentesis is still valuable in patients in whom a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is suspected but who are too unstable to transport for a formal sonographic examination.1

Anatomy

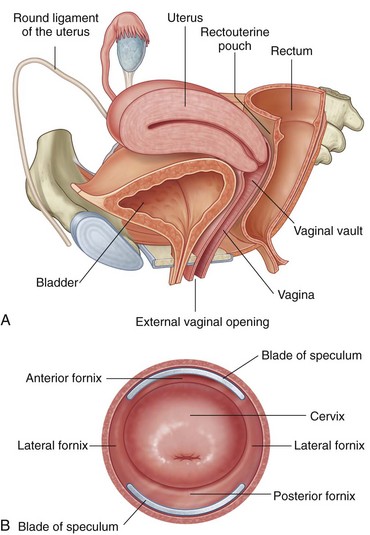

Before attempting culdocentesis, the clinician must be familiar with the anatomy of the vagina and the rectouterine pouch (pouch of Douglas) (Fig. 57-1). In adult women, the vagina is approximately 9 cm long. From its inferior to its superior aspect, the posterior wall of the vagina is related to the anal canal by way of the perineal body, the rectum, and the peritoneum of the rectouterine pouch.2 The uterus lies at nearly a right angle to the vagina. The rectouterine pouch and the posterior wall of the vagina are adjacent only at the upper quarter (≈2 cm) of the posterior vaginal wall. The vaginal wall in this area is less than 5 mm thick.

Indications

Culdocentesis is indicated in any adult woman in whom aspiration of fluid from the rectouterine pouch will help confirm the clinical diagnosis. If ultrasound examination is not readily available in the emergency department (ED) or if the patient is too hemodynamically unstable to be transported to an off-site location for ultrasound, culdocentesis may be the fastest and most accurate diagnostic technique available to the emergency clinician.3 Analysis of peritoneal fluid is also a reliable method of differentiating inflammatory from hemorrhagic pelvic pathologic conditions. Conditions in which culdocentesis may be of diagnostic value include a ruptured viscus (particularly an ectopic pregnancy or a corpus luteum cyst), PID and other intraabdominal infections (particularly appendicitis with rupture or diverticulitis with perforation), intraabdominal injuries to the liver or spleen, and ruptured aortic aneurysms.4

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy is often one of the most difficult gynecologic lesions to diagnose.5 The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is on the rise, and it accounts for 1.6% of all pregnancies. Ectopic pregnancy is the most common obstetric cause of maternal death in the first trimester.5 In a series of 300 consecutive cases of ectopic pregnancy, 50% of patients received medical evaluation at least twice before the correct diagnosis was made.6 In 11% of patients in this series, the diagnosis was not made until the third medical visit.

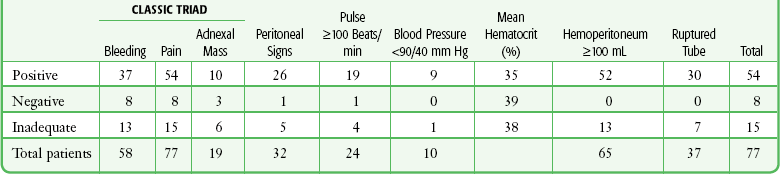

The clinical picture of ectopic pregnancy may include vascular collapse, pelvic pain, isolated rectal or back pain, amenorrhea, abnormal menses, shoulder pain, syncope, cervical or adnexal tenderness, adnexal mass, anemia, and leukocytosis. It is important to note that blood in the peritoneal cavity does not consistently correlate with peritoneal irritation, blood pressure, or pulse rate.7 In fact, bradycardia in the presence of significant intraperitoneal bleeding from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is not unusual (Tables 57-1 and 57-2).

TABLE 57-1

From Cartwright PS, Vaughn B, Tuttle D. Culdocentesis and ectopic pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:88.

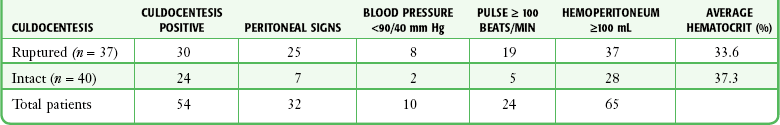

TABLE 57-2

From Cartwright PS, Vaughn B, Tuttle D. Culdocentesis and ectopic pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:88.

Risk factors for an ectopic pregnancy include a history of salpingitis, use of an intrauterine contraceptive device, or tubal ligation; however, no combination of these signs, symptoms, or historical data is diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy. To confuse the diagnosis further, a normal menstrual history is reported in approximately 50% of patients with an ectopic pregnancy. A urine pregnancy test is occasionally negative.8 Though rarely seen, the combination of a uterine decidual cast (Fig. 57-2) and a positive pregnancy test is virtually pathognomonic of an ectopic pregnancy. A uterine cast is decidua that has been hormonally stimulated by the ectopic pregnancy but is passed vaginally when the tissue can no longer be supported. The cast is an outline of the uterine cavity, but it can be mistaken for products of conception if not inspected carefully. Therefore, all tissue passed vaginally should be carefully inspected before being sent to the laboratory for analysis for products of conception. An ectopic pregnancy can occasionally occur in conjunction with an intrauterine pregnancy. Patients who have undergone a therapeutic abortion may actually have had an unrecognized ectopic pregnancy, hence the need for pathologic evaluation of any tissue obtained by uterine evacuation procedures.

The greater sensitivity of the serum and urine β-hCG assay, coupled with the increased availability of emergency medicine physicians trained to perform pelvic ultrasound, has greatly increased the chance of early diagnosis of unruptured and ruptured ectopic pregnancy.9 Urinary β-hCG tests provide a sensitivity to 20 to 50 mIU/mL and are positive in the first few weeks of pregnancy. However, ectopic pregnancy is often associated with very low production of this hormone.

Quantification of the serum test adds additional information since it is sensitive to 5 mIU/mL. Therefore, a negative urine β-hCG test rules out pregnancy in greater than 98% of cases, and pregnancy in any site can be ruled out in virtually all patients with a negative serum β-hCG test.10 A single quantitative β-hCG level is a poor predictor of the size of the pregnancy or the risk for ectopic pregnancy, but serial testing is quite helpful. It is expected that the quantitative serum β-hCG level should double approximately every 2 days in the first trimester.

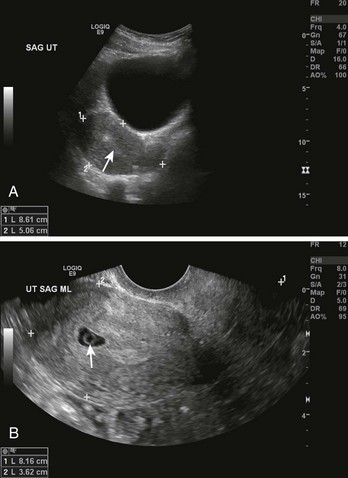

To increase the accuracy of diagnosis, it is helpful to combine quantitative β-hCG testing with ultrasound examination (Fig. 57-3). An empty uterus by transvaginal or abdominal ultrasound combined with certain quantitative serum β-hCG results can be quite helpful to the clinician. The quantitative range in which the ultrasonographer should detect an intrauterine pregnancy varies, but an intrauterine pregnancy should be detected if the serum β-hCG level is in the range of 1200 to 1500 mIU/mL when using a transvaginal probe and greater than 6000 mIU/mL when using a transabdominal probe. Endovaginal ultrasonic scanning consistently identifies a 4-week gestational sac if the β-hCG level is 2000 mIU/mL or greater. The presence of a fetal pole and cardiac activity are detectable with endovaginal ultrasound scanning at approximately 6 and 7 weeks, respectively.11 Note that a heartbeat can occasionally be detected in an ectopic pregnancy or in an extrauterine pregnancy and may be mistakenly deemed intrauterine. It is important to note that the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy by ultrasound, when the β-hCG level is below the discriminatory zone (defined as the hCG level at which a normal intrauterine pregnancy can be detected by ultrasound), is nondiagnostic and could represent an early viable normal pregnancy, a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy, a completed abortion, or an ectopic pregnancy. When no intrauterine pregnancy is detected by ultrasound and the serum β-hCG level exceeds the discriminatory zone, the chance of an ectopic pregnancy ranges from 86% to 100%.12

Culdocentesis may play an important role in some patients in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. The test has an accuracy rate of 85% to 95%.3,13,14 Romero and coworkers15 reported that an ectopic pregnancy was found in 99% of patients with a positive pregnancy test and positive results on culdocentesis. Although culdocentesis is most often positive in the presence of a frankly ruptured ectopic pregnancy, it may be diagnostic even in a nonruptured case when bleeding has been slow or intermittent. Note that many ectopic pregnancies leak varying amounts of blood for days or weeks before rupture. Hemoperitoneum has been found in 45% to 60% of cases of unruptured ectopic pregnancy, as proved at surgery.7,16

Hence, culdocentesis may be helpful in a stable patient whose ultrasound examination does not demonstrate an intrauterine pregnancy despite a quantitative serum β-hCG level in the appropriate range. Although some clinicians opt for outpatient monitoring of serial β-hCG levels in this setting, patients in whom the clinician has high suspicion for an ectopic pregnancy (e.g., a patient who has or had significant discomfort) or in whom close follow-up cannot be ensured may be candidates for culdocentesis.3 Even though a negative finding on culdocentesis does not rule out an early ectopic pregnancy, patients with a nondiagnostic ultrasound and a negative culdocentesis generally represent those at lower risk for “rupture” of an ectopic pregnancy during outpatient serum β-hCG monitoring. Patients with a nondiagnostic ultrasound examination and a serum β-hCG level below the threshold at which an intrauterine pregnancy should be visible on the ultrasound examination must be individualized. These patients, especially those with significant pain, an unexplained low hematocrit, or postural changes in vital signs (or near syncope), might be candidates for culdocentesis.

Blunt Abdominal Trauma

Historically, diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) and computed tomography (CT) have been used to identify hemoperitoneum in blunt trauma patients. The use of culdocentesis has also been advocated to aid in this diagnosis.4,17 In the ED, two factors have largely obviated the need to perform invasive procedures for diagnosis of hemoperitoneum: (1) the increasing availability of high-resolution CT and (2) emergency clinicians trained to perform the bedside ultrasound FAST (focused assessment with sonography for trauma) examination. However, because small amounts of blood tend to collect in the rectouterine pouch, aspiration of clear peritoneal fluid is of great potential value in excluding a diagnosis of hemoperitoneum. This is especially helpful in situations in which ultrasound is unavailable or the patient is too unstable to leave the ED for a CT scan. In fact, culdocentesis may be more advantageous than DPL in some instances because there is less risk for urinary bladder perforation or bowel injury. In addition, previous abdominal surgery is not a relative contraindication to culdocentesis, as it is with DPL.18

Contraindications

Contraindications to culdocentesis are relatively few and include an uncooperative patient, a pelvic mass detected on bimanual pelvic examination, a nonmobile retroverted uterus, and coagulopathies. Pelvic masses may include tuboovarian abscesses, appendiceal abscesses, ovarian masses, and pelvic kidneys. It has been suggested that the only major risk with the procedure is rupture of an unsuspected tuboovarian abscess into the peritoneal cavity. This can be avoided by careful bimanual pelvic examination to exclude patients with large masses in the cul-de-sac.19 Although no data are available to guide the age at which culdocentesis may be performed safely, the procedure is generally limited to patients beyond puberty. This limitation is suggested on the basis of anatomy and with the consideration that the procedure is difficult to perform through a small prepubertal vagina.

Equipment

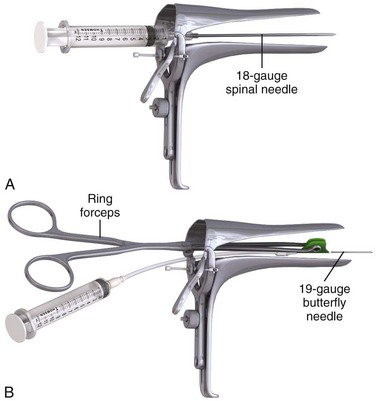

The equipment required for culdocentesis is depicted in Review Box 57-1. Either an 18-gauge spinal needle or a 19-gauge butterfly needle held by ring forceps is acceptable. It may be helpful to anesthetize the posterior vaginal wall at the site of the puncture with 1% to 2% lidocaine with epinephrine administered through a 27-or 25-gauge needle. Some physicians use a topical anesthetic (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics [EMLA], benzocaine) or a cocaine-soaked cotton ball to anesthetize the mucosa before infiltration with a local anesthetic. Although local anesthesia is often unnecessary (because puncture of the posterior vaginal wall at the upper fourth of the vagina is generally no more painful than a venipuncture), there is some advantage to using a local anesthetic if multiple attempts at culdocentesis are required, as is sometimes the case. In addition, the epinephrine may produce vasoconstriction and reduce bleeding associated with the needle puncture. Culdocentesis is often stressful to the patient, and all attempts should be made to render the procedure as painless as possible. Parenteral analgesia and sedation should also be considered when the patient is uncomfortable or anxious.

Technique

Exposure

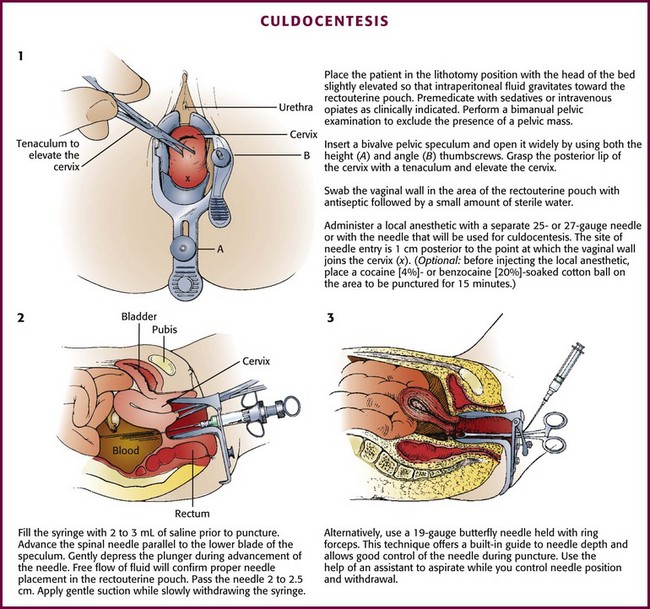

Perform a bimanual pelvic examination before culdocentesis to rule out a fixed pelvic mass and to assess the position of the uterus. It is possible to palpate an adnexal mass if the mass exceeds 3 cm in diameter. Insert a bivalve vaginal speculum and open it widely by adjusting both the height and the angle thumbscrews (Fig. 57-4, step 1). Grasp the posterior lip of the cervix with the toothed uterine cervical tenaculum and elevate the cervix. Warn the patient in advance that she may feel a sharp pain when the cervix is grasped with the tenaculum. Inform the patient also that bleeding from the tenaculum puncture site or culdocentesis site, or both, may produce postprocedural spotting.

Aspiration

Following local anesthesia, advance the syringe and the spinal needle parallel to the lower blade of the speculum (Fig. 57-4, step 2). Fill the syringe with 2 to 3 mL of saline (nonbacteriostatic) before puncture. After needle puncture, the free flow of fluid from the syringe will expel tissue that may have clogged the needle and will confirm that the tip of the needle is in the proper position and not lodged in the uterine wall or the intestinal wall. Use saline rather than air because if air is used, it may be difficult to interpret the presence of free peritoneal air on subsequent radiographs. To avoid the need to change the syringe during the procedure, use 1% lidocaine for both anesthesia and confirmation of proper needle placement; however, the bacteriostatic property of this agent precludes its use if the procedure is performed to obtain fluid for culture.

Penetrate the vaginal wall in the midline 1 to 1.5 cm posterior (inferior) to the point at which the vaginal wall joins the cervix (Fig. 57–4, step 2).20 Pass the needle a total of 2 to 2.5 cm.20,21 Apply gentle suction with the syringe while slowly withdrawing the needle. Avoid aspirating any blood that has accumulated in the vagina from previous needle punctures or from cervical bleeding because this may give the false impression of a positive tap. Bleeding from the puncture site in the vaginal wall can be minimized by adding epinephrine to the local anesthetic.

Some physicians prefer the use of a 19-gauge butterfly needle held with ring forceps (Fig. 57-4, step 3, and Fig. 57-5).20 This technique offers a built-in guide to needle depth and allows good control of the needle during puncture. An assistant must aspirate the tubing while the physician controls positioning and withdrawal of the needle.

Interpretation of Results

Interpretation of the results of culdocentesis depends primarily on whether any fluid was obtained. It should be noted that in the absence of a pathologic condition, 2 to 3 mL of clear yellowish peritoneal fluid can be aspirated. When there is no return of fluid of any type (a so-called dry tap), the procedure has no diagnostic value. Because a dry tap is nondiagnostic, it should not be equated with normal peritoneal fluid. In addition, when less than 2 mL of clotting blood is obtained, this is also considered to be a nondiagnostic tap because the source of this small amount of blood may be the puncture site on the vaginal wall. Such blood will usually clot. More than 2 mL of nonclotting blood is certainly suggestive of hemoperitoneum. However, some researchers interpret as little as 0.3 mL of nonclotting blood as a positive tap.7 There is no particular significance of larger amounts of blood because absolute volume may be related to the position of the needle or the rate of bleeding. Brenner and colleagues6 reported no blood from culdocentesis in 5% of patients with proven ectopic pregnancies even when rupture had occurred. In the series of 61 patients with surgically proven ectopic pregnancy reported by Cartwright and associates,7 culdocentesis performed within 4 hours of surgery was positive in 70%, negative in 10%, and inadequate in 20%. “Positive” in their series was defined as obtaining at least 0.3 mL of nonclotting blood with a hematocrit of greater than 3%. “Negative” was defined as obtaining 0.3 mL of fluid with a hematocrit of less than 3%. An “inadequate” tap was one in which no fluid was obtained. In the 252 patients reported by Vermesh and coworkers16 who had surgically proven ectopic pregnancies and underwent culdocentesis, 83% had a positive tap. They defined a positive tap as nonclotting blood with a hematocrit of greater than 15%.

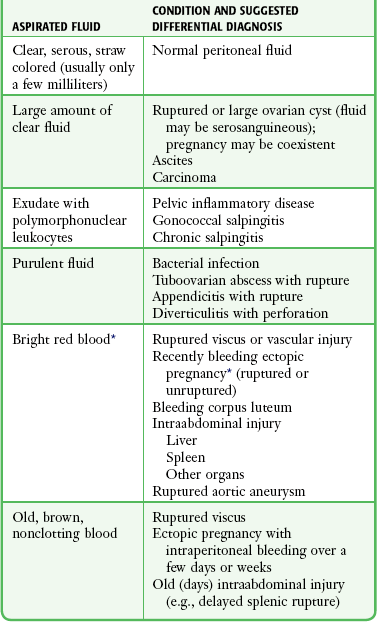

When culdocentesis is used to diagnose a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, a “negative tap” is one that yields pus or clear, straw-colored peritoneal or cystic fluid. A large amount of clear fluid (>10 mL) indicates a probable ruptured ovarian cyst, aspiration of an intact corpus luteal cyst, ascites, or possibly carcinoma. The significance of this fluid and interpretation of the results are outlined in Table 57-3 and Box 57-1. Elliot and colleagues22 cautioned that obtaining greater than 10 mL of clear fluid should not automatically rule out an ectopic pregnancy because the latter may coexist with other pathologic conditions.

TABLE 57-3

Interpretation of Culdocentesis Fluid

*Note: The hematocrit of blood from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is usually 15% or greater (97.5% of cases), but some authors use greater than 3% as positive.

A “positive tap” is one in which nonclotting blood is obtained, although the presence of nonclotted blood does not confirm a tubal pregnancy. Intraperitoneal blood from any source (ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cyst, ruptured spleen) may remain unclotted after aspiration for days in the syringe as a result of the defibrination activity of the peritoneum. Return of serosanguineous fluid also suggests a ruptured ovarian cyst. The hematocrit of blood from active intraperitoneal bleeding is greater than 10%. In one series, the hematocrit of blood from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy was 15% or greater in 97% of cases.6

It should be emphasized that a positive finding on culdocentesis in the presence of a positive pregnancy test does not always prove an ectopic pregnancy.16 A ruptured corpus luteum cyst in the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy test is probably the most common cause of a false-positive scenario. Whenever possible, ultrasound can help corroborate the findings on culdocentesis.

Complications

Culdocentesis is one of the safest procedures performed in the emergency setting, and there are probably fewer complications with this technique than with peripheral venous cannulation. Complications have been reported, however, the most serious being rupture of an unsuspected tuboovarian abscess.20 Other complications include perforation of the bowel, perforation of a pelvic kidney, and bleeding from the puncture site in patients with clotting disorders. Because the most common complications result from puncture of a pelvic mass, careful bimanual examination of the patient should help prevent this problem. Puncture of the bowel and the uterine wall occurs relatively frequently but does not generally result in serious morbidity. Obviously, penetration of a gravid uterus has greater potential for harm. Occasionally, one will aspirate air or fecal matter, thereby confirming inadvertent puncture of the rectum.

References

1. Graczykowski, JW, Seifer, DB. Diagnosis of acute and persistent ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42:9.

2. Ellis H, ed. Clinical Anatomy: A Revision and Applied Anatomy for Clinical Students, 5th ed, Oxford, Blackwell Scientific, 1972:129.

3. Vande Krol, L, Abbott, JT. The current role of culdocentesis. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:354.

4. Clarke, JM. Culdocentesis in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969;129:809.

5. Goldner, TE, Lawson, HW, Xia, Z, et al. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1970-1989. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993;42(6):73–86.

6. Brenner, PF, Roys, S, Mishell, DR. Ectopic pregnancy: a study of 300 consecutive surgically treated cases. JAMA. 1980;243:673.

7. Cartwright, PS, Vaughn, B, Tuttle, D. Culdocentesis and ectopic pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:88.

8. Kistner, RW. The oviduct-tubal ectopic pregnancy. In: Kistner RW, ed. Gynecology: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Chicago: Year Book Medical; 1971:304.

9. Chung, SJ. Review of pregnancy tests. South Med J. 1981;74:1387.

10. Brennan, DF. Ectopic pregnancy: I. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:1081.

11. Durham, B, Lane, B, Burbridge, L, et al. Pelvic ultrasound performed by emergency physicians for the detection of ectopic pregnancy in complicated first trimester pregnancies. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:338.

12. Brennan, DF. Ectopic pregnancy: II. Diagnostic procedures and imaging. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:1090.

13. Hall, RE, Todd, WD. The suspected ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;81:1220.

14. Webster, HD, Barclay, DL, Fischer, CK. Ectopic pregnancy: a seventeen-year review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;92:23.

15. Romero, R, Copel, JA, Kadar, N, et al. Value of culdocentesis in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:519.

16. Vermesh, M, Graczykowski, JW, Sauer, MV. Reevaluation of the role of culdocentesis in the management of ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:411.

17. Generelly, P, Moore, TA, LeMay, JT. Delayed splenic rupture: diagnosed by culdocentesis. JACEP. 1961;6:369.

18. Olsen, WR. Peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. JACEP. 1973;2:271.

19. Chow, AW, Malkasian, KL, Marchall, JR, et al. The bacteriology of acute pelvic inflammatory disease, value of cul-de-sac cultures and relative importance of gonococci and other aerobic or anaerobic bacteria. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;122:876.

20. Webb, MJ. Culdocentesis. JACEP. 1978;7:12.

21. Lucas, C, Hassim, AM. Place of culdocentesis in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Br Med J. 1970;1:200.

22. Elliot, M, Riccio, J, Abbott, J. Serous culdocentesis in ectopic pregnancy: a report of two cases caused by co-existent corpus luteum cysts. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:407.