Critical Care Nursing Practice

History of Critical Care

Critical care evolved from the recognition that the needs of patients with acute, life-threatening illness or injury could be better met if the patients were organized in distinct areas of the hospital. In the 1800s, Florence Nightingale described the advantages of placing patients recovering from surgery in a separate area of the hospital. A three-bed postoperative neurosurgical intensive care unit was opened in the early 1900s at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. This was soon followed by a premature infant unit in Chicago.1

Contemporary Critical Care

These nurses practice in a variety of settings: adult, pediatric, and neonatal critical care units; step-down, telemetry, progressive, or transitional care units; cardiac catheterization laboratories; and postoperative recovery units.2 Nurses are now considered to be knowledge workers because they are highly vigilant and use their intelligence and cognition to go past tasks in order to quickly pull together multiple data to make decisions regarding subtle and/or deteriorating conditions. Nurses work technically with theoretical knowledge.3

A growing trend in acute care settings is the designation of progressive care units, considered to be part of the continuum of critical care. In past years, patients who are placed on these units would have been exclusively in critical care units. However, with the use of additional technology and monitoring capabilities, newer care delivery models, and additional nurse education, these units are considered the best environment. The patients are less complex, more stable, have a decreased need for physiologic monitoring, and more self-care capabilities. They can serve as a bridge between critical care units and medical-surgical units, while providing high quality and cost effective care at the same time.4 Additionally, these progressive units can be found throughout the acute care setting, thus leaving critical care unit beds for those who need the highest level of care and monitoring.5

Critical Care Nursing Roles

Nurses provide and contribute to the care of critically ill patients in a variety of roles. The most prevalent role for the professional registered nurse is that of direct care provider. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) has delineated role responsibilities important for the critical care nurse5 (Box 1-1).

Advanced Practice Nurses

NPs and ACNPs manage direct clinical care of a group of patients and have various levels of prescriptive authority, depending on the state and practice area in which they work. They also provide care consistency, interact with families, plan for patient discharge, and provide teaching to patients, families, and other members of the health care team.6

Critical Care Professional Accountability

Professional organizations support critical care practitioners by providing numerous resources and networks. The Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) is a multidisciplinary, multispecialty, international organization. Its mission is to secure the highest quality, cost-efficient care for all critically ill patients.1 Numerous publications and educational opportunities provide cutting-edge critical care information to critical care practitioners.

The organization most closely associated with critical care nurses is the AACN. It is the world’s largest specialty nursing organization and was created in 1969. AACN is focused on “creating a healthcare system driven by the needs of patients and their families, where acute and critical care nurses make their optimal contribution.”7 The top priority of the organization is education of critical care nurses. AACN publishes numerous materials, evidence-based practice summaries, and practice alerts related to the specialty and is at the forefront of setting professional standards of care.

AACN serves its members through a national organization and many local chapters. The AACN Certification Corporation, a separate company, develops and administers many critical care specialty certification examinations for registered nurses. The examinations are provided in specialties such as neonatal, pediatric, and for those who practice in diverse settings, such as critical care, progressive care, “virtual” ICU, or remote monitoring (e-ICU). Certification is considered one method to maintain high quality of care and to protect consumers of care and services. Research has demonstrated more positive outcomes when care is delivered by health care providers who are certified in their specialty.8 AACN also recognizes critical care and acute care units who achieve a high level of excellence through its Beacon Award for Excellence. The unit that receives this award has demonstrated exceptional care through improved outcomes and greater overall satisfaction. It reflects on a supportive overall environment, teamwork and collaboration, and distinguishes itself with lower turnover and higher morale.9

Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

Much of early medical and nursing practice was based on non-scientific traditions, intuition, and traditions. These traditions and rituals, which were based on folklore, gut instinct, trial and error, and personal preference, were often passed down from one generation of practitioner to another. Examples of non–scientific-based critical care nursing practice include Trendelenburg positioning for hypotension, use of rectal tubes to manage fecal incontinence, gastric residual volume and aspiration risk, accuracy of assessment of body temperature, and suctioning artificial airways every 2 hours—to name a few. In order to deliver the highest quality of care, EBP is essential and must be embraced by all nurses.10

The dramatic and multiple changes in health care and the ever-increasing presence of managed care in all geographic regions have placed greater emphasis on demonstrating the effectiveness of treatments and practices on outcomes. Emphasis is on greater efficiency, cost-effectiveness, quality of life, and patient satisfaction ratings. It has become essential for nurses to use the best data available to make patient care decisions and carry out the appropriate nursing interventions.10–11 By using an approach employing a scientific basis, with its ability to explain and predict, nurses are able to provide research-based interventions with consistent, positive outcomes. The content of this book is research-based, with the most current, cutting-edge research abstracted and placed throughout the chapters as appropriate to topical discussions.

The increasingly complex and changing health care system presents many challenges to creating an EBP. Appropriate research studies must be designed to answer clinical questions, and research findings must be used to make necessary changes for implementation in practice. Multiple EBP and research utilization models exist to guide practitioners in the use of existing research findings. One such model is the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care, which incorporates evidence and research as the bases for practice.12 Cullen and Adams describe a framework with four key phases to implement EBP: 1) create awareness and interest; 2) build knowledge and commitment; 3) promote action and adoption; and 4) pursue integration and sustained use. Each step has multiple strategies that will facilitate successful progression to the next phase. The authors indicate that this model is particularly suited to complex static organizations.11

Just as there has been such an exponential growth of EBP literature, reports, publications and acceptance, others are posing the question, “But at what cost?” Newhouse describes this as a complex issue to address and states that economists would go beyond the costs of human labor and materials in their analysis. Another way to evaluate this is to examine “whose” cost is being considered.13 More recently, a published article reported estimates of costs per event for several health-acquired conditions (HACs). The estimated cost of care for one catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) was $758. A patient fall was estimated to be $4,233 per fall; and a surgical “never event” cost $62,000 per event. These are most likely underestimated; but it is easy to realize the tremendous impact of situations that should not occur because there is sufficient evidence to prevent such outcomes.14 Thus, inquisitive practitioners who strive for best practices using valid and reliable data will demonstrate quality outcomes-driven care and practices.

Evidence-based nursing practice considers the best research evidence on the care topic, along with clinical expertise of the nurse, and patient preferences. For instance, when determining the frequency of vital sign measurement, the nurse would use available research, nursing judgment (stability, complexity, predictability, vulnerability, and resilience of the patient),15 along with the patient’s preference for decreased interruptions and the ability to sleep for longer periods of time. At other times the nurse will implement an evidence-based protocol or procedure that is based on evidence, including research. An example of an evidence-based protocol is one in which the prevalence of indwelling catheterization and incidence of hospital-acquired catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the critical care unit can be decreased.16

The AACN has promulgated several EBP summaries in the form of a “Practice Alert.” These alerts are short directives that can be used as a quick reference for practice areas (e.g., oral care, noninvasive blood pressure monitoring, ST segment monitoring). They are succinct, supported by evidence, and address both nursing and multidisciplinary activities. Each alert includes the clinical information, followed by references that support the practice.17 An example of one of the alerts is found on in Box 1-2.

Holistic Critical Care Nursing

Caring

The high technology–driven critical care environment is fast paced and directed toward monitoring and treating life-threatening changes in patients’ conditions. For this reason, attention is often focused on the technology and treatments necessary for maintaining stability in the physiologic functioning of the patient. Great emphasis is placed on technical skills and professional competence and responsiveness to critical emergencies. Concern has been voiced about the diminished emphasis on the caring component of nursing in this fast-paced, highly technologic health care environment.18,19 Nowhere is this more evident than in areas in which critical care nursing is practiced. It has been said that keeping the care in nursing care is one of our biggest challenges.19 The critical care nurse must be able to deliver high-quality care skillfully, using all appropriate technologies, while incorporating psychosocial and other holistic approaches as appropriate to the time and condition of the patient.

The caring aspect between nurses and patients is most fundamental to the relationship and to the health care experience. The literature demonstrates that nurse clinicians focus on psychosocial aspects of caring, whereas patients place more emphasis on the technical skills and professional competence.20 Physical and emotional absence, inhumane and belittling interactions, and lack of recognition of the patient’s uniqueness indicate noncaring. Holistic care focuses on human integrity and stresses that the body, the mind, and the spirit are interdependent and inseparable. All aspects need to be considered in planning and delivering care.21

Individualized Care

An important aspect in the care delivery to and recovery of critically ill patients is the personal support of family members and significant others. The value of patient- and family-centered care should not be underestimated.22,23 It is important for families to be included in care decisions and to be encouraged to participate in the care of the patient as appropriate to the patient’s personal level of ability and needs.

Cultural Care

Cultural diversity in health care is not a new topic, but it is gaining emphasis and importance as the world becomes more accessible to all as the result of increasing technologies and interfaces with places and peoples. Diversity includes not only ethnic sensitivity but also sensitivity and openness to differences in lifestyles, opinions, values, and beliefs. More than 28% of the U.S. population is made up of racial and ethnic minority groups.24 The predominant minorities in the United States are Americans of African, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Island, Native American, and Eskimo descent. Significant differences exist among their cultural beliefs and practices and the level of their acculturation into the mainstream American culture.25

Cultural competence is one way to ensure that individual differences related to culture are incorporated into the plan of care.26–27 Nurses must possess knowledge about biocultural, psychosocial, and linguistic differences in diverse populations to make accurate assessments. Interventions must then be tailored to the uniqueness of each patient and family.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Consumer activism has increased, and consumers are advocating for quality health care that is cost-effective and humane. They are asking whether options other than traditional Western medical care exist for treating various diseases and disorders. The possibilities of using centuries-old practices that are considered alternative or complementary to current Western medicine have been in demand.28–29 These types of therapies can be seen in all health care settings, including the critical care unit. Complementary therapies offer patients, families, and health care providers additional options to assist with healing and recovery.30

Two terms, alternative and complementary, have been in the mainstream for several years. Alternative denotes that a specific therapy is an option or alternative to what is considered conventional treatment of a condition or state. The term complementary was proposed to describe therapies that can be used to complement or support conventional treatments.30 The remainder of this section includes a brief discussion about nontraditional complementary therapies that have been used in critical care areas.

Spirituality and Prayer

As persons search for meaning and guidance in critical, emergent, and unexpected tragic circumstances, spirituality becomes more important.31 Likewise, health care practitioners turn to their own spirituality to manage stress and find answers to the health care issues that they face on an intense, daily basis. Spiritual practices consist of meditation, prayer, and spiritual materials and are based on personal values and beliefs.32 Holt-Ashley31 describes how to incorporate prayer into the critical care unit, concentrating on patients, their families, and the nurse. The study author also offers strategies for creating an environment that is conducive to spiritual well-being for patients and staff.

Guided Imagery

One of the most well-studied complementary therapies is guided imagery, a mind-body strategy that is frequently used to decrease stress, pain, and anxiety.33 Additional benefits of guided imagery are: 1) decreased side effects; 2) decreased length of stay; 3) reduced hospital costs; 4) enhanced sleep; and 5) increased patient satisfaction.33 Guided imagery is a low-cost intervention that is relatively simple to implement. The patient’s involvement in the process offers a sense of empowerment and accomplishment and motivates self-care.

Massage

A comprehensive review of the literature revealed that the most common effect of massage was reduction in anxiety, with additional reports of a significant decrease in tension. There was also a positive physiologic response to massage in the areas of decreased respiratory and heart rates and decreased pain. The effects on sleep were inconclusive. The study authors concluded that massage was an effective complementary therapy for promoting relaxation and reducing pain, and they thought it should be incorporated into nursing practice.34

Animal-Assisted Therapy

The use of animals has increased as an adjunct to healing in the care of patients of all ages in various settings. Pet visitation programs have been created in various health care delivery settings,35 including acute care, long-term care, and hospice. In the acute care setting, animals are brought in to provide additional solace and comfort for patients who are critically or terminally ill. Fish aquariums are used in patient areas and family areas, because they humanize the surroundings. Scientific evidence indicates that animal-assisted therapy results in positive patient outcomes in the areas of attention, mobility, and orientation. Other reports have shown improved communication and mood in patients.36

Nursing’s Unique Role in Health Care

Today’s health care environment necessitates a nursing framework that is flexible and responsive to the needs of the public that is served. The American Nurses Association (ANA) has defined nursing as the “protection, promotion, and optimization of health, and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and populations.”37 Although nursing has independent and dependent nursing actions, it is essential that an interdependence with all health care professionals is actualized.

Critical Care Nursing Practice

Researchers have studied critical care nurses to better understand their clinical judgment and interventions and the link between the two. They identified two major categories of thought and action and nine categories of practice that illustrate clinical judgment and the clinical knowledge development of critical care nurses.38 These major categories are delineated in Box 1-3.

The Nursing Process

Nursing Diagnosis

The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) has supported the continued development and evolution of research-based nursing diagnoses.39 With nursing diagnosis as a component of the decision-making method, there is a more systematic collection and interpretation of data. The most essential and distinguishing feature of any nursing diagnosis is that it describes a health condition primarily resolved by nursing interventions or therapies.

Nursing Interventions

The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) framework contains 544 nursing interventions that are categorized into 30 classes and 7 domains.40 Many nursing interventions are directly linked with NANDA nursing diagnoses. Nurse-initiated treatments are interventions initiated by the nurse in response to a nursing diagnosis. The use of the NIC framework facilitates clinical decision making and provides a standardized language that describes the core of essential nursing interventions. An example of an NIC nursing intervention on surveillance is presented in Box 1-4. The research base provides a method to link diagnoses with outcomes in the evaluation of care and services.40

Technology in Critical Care

The growth in technologies has been seen throughout health care, especially in critical care settings. All providers are challenged to learn new equipment, monitoring devices, and related therapies that contribute to care and services. Take, for example, the evolving electronic health record (EHR) that was originally designed to capture data for clinical decision making and to increase the efficiency of health care providers. There are complexities inherent in providing a “user-friendly” EHR. Thus, one that meets the needs and reflects the thought processes and actual work flow of diverse clinicians has been greatly lacking. Add to that the fact that staff-created “work-arounds” to some of the software/procedures have not significantly reduced errors or increased productivity. There is a tremendous amount of data, but those data are not turned into meaningful information on which to make decisions.41 For this reason, it is important that critical care nurses are involved in the selection, trial, education, and evaluation of any health care informatics technologies that are being considered for their practice areas. Nurse informaticians, clinical nurse specialists, educators, and managers are also essential in the selection processes so that all aspects are considered.42 Another area for critical care nurse involvement is in assessing new products that come into the system. Often, there are numerous “avenues” that products enter, such as product fairs, individual physicians, vendors, and supply departments, to name a few. It is important that all proposed new products are overseen by a central committee or group who establishes criteria by which to select, pilot, evaluate, adopt, and communicate about the new product. Some criteria that can be used in the initial assessment are: 1) clinical relevance; 2) clinical void; 3) cost; 4) extra costs; and 5) safety.43 This type of process ensures consistency and the same standards regarding product selection across the organization.

A more recent opportunity for critical care nurses is working in a role that encompasses the Tele-ICU. Telemedicine was initially employed in outpatient areas, remote, rural geographic locations, and areas where there was a dearth of medical providers. Currently, there are Tele-ICUs in areas where there are limited resources on site. However, there are experts (critical care nurses, intensivists) located in a central distant site. Technologies relay continuous surveillance with monitoring information and communication among care providers. Each Tele-ICU varies in size and location; the key component is the availability of back-up experts. Goran describes competencies for critical care nurses who practice in a Tele-ICU.44

Interprofessional Collaborative Practice

The growing managed care environment has placed emphasis on examining methods of care delivery and processes of care by all health care professionals. Collaboration and partnerships have been shown to increase quality of care and services while containing or decreasing costs.45–50 It is more important than ever to create and enhance partnerships, because the resulting interdependence and collaboration among disciplines is essential to achieving positive patient outcomes. A recent article reported a study in which physician-nurse relationships improved collaboration after meeting together to create a method to change the unit culture. They met together to examine collaboratively on what the issues were and create strategies to resolve them. There were higher scores on openness of communication within groups, between groups, accuracy between groups, and overall collaboration.51

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IEC) published their Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice in 2011. The IEC sponsors include the American associations of nursing, dentistry, medicine, osteopathy, public health, and pharmacy. Their goal was to establish a set of competencies to serve as a framework for professional socialization of health care professionals. They also intended to assess the relevance of the competencies and develop an action plan for implementation.52 These competencies are especially important at this time as we move forward with health care reform and explore innovative care delivery models using the skill sets of all health care providers in the most effective and efficient manner. Box 1-5 delineates the four core competencies.

Interdisciplinary Care Management Models and Tools

Care Management Tools

Many quality improvement tools are available to providers for care management. The three evidence-based tools addressed in this chapter are clinical algorithm, practice guideline, and protocol.53 All of these tools may be embedded in the EHR.

Quality, Safety, and Regulatory Issues in Critical Care

Quality and Safety Issues

Patient safety has become a major focus of attention by health care consumers, providers of care, and administrators of health care institutions. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) publication Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century was the impetus for debate and actions to improve the safety of health care environments. In this seminal report, information and details were given indicating that health care harms patients too frequently and routinely fails to deliver its potential benefits.54 Often, the definitions of medical errors and approaches to resolving patient safety issues differ among nurses, physicians, administrators, and other health care providers.55 Subsequently through its use of expert panels, the IOM has published numerous other important reports related to quality, safety, and the nursing environment.

Patient safety has been described as an ethical imperative, and one that is inherent in health care professionals’ actions and interpersonal processes.56 In critical care units errors may occur because of the hectic, complex environment, where there is little room for error and safety is essential.56–57 In this environment, patients are particularly vulnerable because of their compromised physiologic status, multiple technologic and pharmacologic interventions, and multiple care providers who frequently work at a fast pace. It is essential that care delivery processes that minimize the opportunity for errors are designed and that a “safety culture” rather than a “blame culture” is created.58 One author discussed results of a research study in which nurses were hesitant to report medication errors or unsafe practices so that they would not be ridiculed or “talked about” by their peer nurses. This uncivil behavior was thought to continue to contribute to an unsafe environment and one in which true error or unsafe practices and systems were greatly unreported.59

Medication administration continues to be one of the most error-prone nursing interventions for the critical care nurse.60 Many medication errors are related to system failures, with distraction as a major factor. Various interventions have been created in an attempt to decrease medication errors. One article reported establishing a “no interruption zone” for medication safety in a critical care unit. In this pilot study, there was a 40% decrease in interruptions from the baseline measurement. Although researchers questioned the feasibility of sustaining this decrease in interruptions in the future,61 this is an example of an approach that could be used to increase medication safety in the critical care unit.

It has been shown that intimidating and disruptive clinician behaviors can lead to errors and preventable adverse patient outcomes. Verbal outbursts, physical threats, and more passive behaviors such as refusing to carry out a task or procedure are all under this category. Unfortunately, these types of behavior are not rare in health care organizations. If these behaviors go unaddressed, it can lead to extreme dissatisfaction, depression, and turnover. There also may be systems issues that lead to or perpetuate these situations, such as push for increased productivity, financial constraints, fear of litigation, and embedded hierarchies in the organization.58

Technologies are both a solution to error-prone procedures and functions, and another potential cause for error. Consider bar-code medication administration procedures, multiple bedside testing devices, computerized medical records, bedside monitoring, computerized physician order entry (CPOE), and many other technologies now in development. Each in itself can be a great assistance to the clinician, but must be monitored for effectiveness and accuracy to ensure the best in outcomes as intended for specific use.60

Quality and Safety Regulations

The Joint Commission (TJC) is an independent, not-for-profit organization that certifies more than 19,000 health care organizations in the United States. Its goal is to evaluate these health care entities using their pre-established standards of performance to ensure high levels of care are provided in these entities. Annually, it establishes National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs)62 that are to be implemented in health care organizations (Box 1-6).

The Safe Medical Device Act (SMDA) requires that hospitals report serious or potentially serious device-related injuries or illness of patients and/or employees to the manufacturer of the device, and if death is involved, to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In addition, implantable devices must be documented and tracked.63– This reporting serves as an early warning system so that the FDA can obtain information on device problems. Failure to comply with the act will result in civil action.

Quality and Safety Resources

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to medication error prevention and safe medication use. It has numerous tools to assist care providers, including newsletters, education programs, safety alerts, consulting, patient education materials, error reporting system, and more. One newsletter is devoted specifically to nurses. It offers a very comprehensive array of tools.64

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) is an interdisciplinary organization focused on quality that also offers many tools and resources: educational materials, conferences, case studies, publications, white papers, quality measure tools, plus many more. IHI developed the “bundle” concept, which consists of EBPs on specific high-risk quality issues as determined by a multidisciplinary group. There are many bundles published by IHI, such as central line, ventilator, and sepsis.65 The National Quality Forum (NQF) is also a not-for-profit organization that facilitates consensus-building with multiple partners to establish national priorities and goals for performance improvement. They also establish common definitions and consistent measurement. In addition, their goal is that all health care providers and stakeholders are educated regarding quality, priorities, and outcomes.66 The Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) is an interdisciplinary organization focused on patient safety and quality of care. They specifically focus on integration of patient safety tools and practices to enhance communication, quality, efficiency, productivity, and clinical support systems.67 A national quality database devoted entirely to nursing is the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). The program provides ongoing nurse-sensitive indicator consultation and research-based expertise. Their mission is to aid the registered nurse in patient safety and quality improvement efforts. It is the only nursing national quality measurement program that provides hospitals with unit-level quality performance comparison reports.68

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project established standards for educating registered nurses at the baccalaureate and master’ levels of academic education. In this model, the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) were created so that nurses would be able to continuously improve the quality and safety of the health care systems for which they work. There are six major categories that delineate the KSAs for each section (Box 1-7).69 Boxes that address one of the QSEN competencies will be presented throughout the book, with the QSEN icon ![]() appearing in them. Box 1-8, Internet Resources, lists the website addresses of all of the quality, safety, and regulatory resources detailed above.

appearing in them. Box 1-8, Internet Resources, lists the website addresses of all of the quality, safety, and regulatory resources detailed above.

Privacy and Confidentiality

A landmark law was passed to provide consumers with greater access to health care insurance, promote more standardization and efficiency in the health care industry, and protect the privacy of health care data.70 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) has created additional challenges for health care organizations and providers because of the stringent requirements and additional resources needed to meet the requirements of the law. Most specific to critical care clinicians is the privacy and confidentiality related to protection of health care data. This has implications when interacting with family members and others, and the oftentimes very close work environment, tight working spaces, and emergency situations. Clinicians are referred to their organizational policies and procedures for specific procedures for their organizations.

Healthy Work Environment

There is an increasing amount of evidence that unhealthy work environments lead to medical errors, suboptimal safety monitoring, ineffective communication among health care providers, and increased conflict and stress among care providers. Synthesis of research in the area of work environment has demonstrated that a combination of leadership styles and characteristics contributes to the development and sustainability of healthy work environments.71

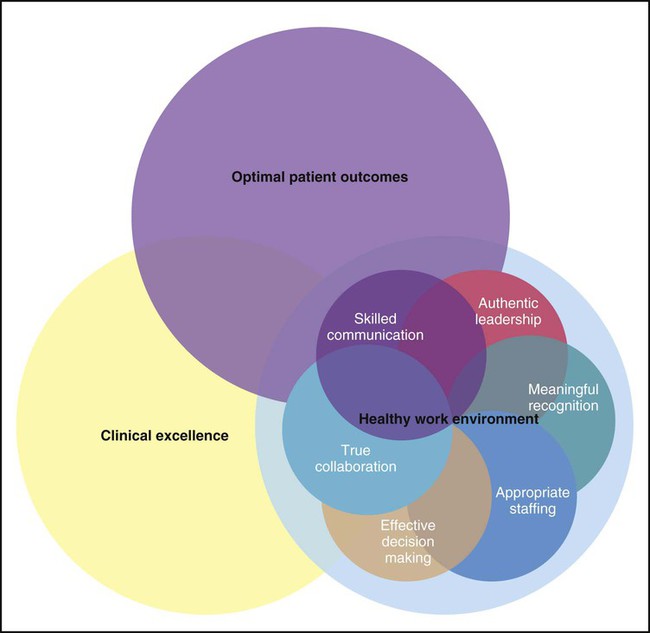

The AACN has formulated standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments (HWE).72 The intent of the standards is to promote creation of environments that will have a positive impact on nursing and patient outcomes. Evidence-based and relationship-centered principles were used to create the standards of professional performance. A summary of the six standards is provided in Box 1-9. Figure 1-1 illustrates the interdependence of each standard, and the ultimate impact on optimal patient outcomes and clinical excellence.

Everyone has a role in creating and sustaining a healthy work environment. Although the manager has a major role in establishing the culture, it is the staff who greatly impact the culture by mentoring new staff, role modeling behaviors, and leading interdisciplinary teams. It is this peer pressure that has the most impact on all other staff.73–74 Bylone discussed her experience of talking with many staff members about how they think that they can influence the work unit culture. She recommends asking them how they influence each of the HWE standards, thus making it a personal experience and journey in achieving the HWE.75 Kupperschmidt and colleagues posed a five-factor model for becoming a skilled communicator: 1) becoming aware of self-deception; 2) becoming authentic; 3) becoming candid; 4) becoming mindful; and 5) becoming reflective; all of which lead to being a skilled communicator, thus creating a healthy work environment.76 An additional approach for implementing the HWE model was offered by Blake, who suggested five steps: 1) rallying the team; 2) surveying the team; 3) establishing work groups; 4) setting goals and developing action steps; and 5) celebrating successes along the way.77 Whatever approach taken will depend on the passion and commitment of the team.

Summary

• Sensitivity to appropriate times to eliminate or modify practices and adopt innovations is key to maintaining quality, cost-effective care delivery.

• It is essential for nurses to use the best data available to make patient care decisions and to carry out the appropriate interventions.

• The critical care nurse must be able to deliver high-quality care skillfully, using all appropriate technologies while incorporating psychosocial and other holistic approaches as appropriate to the time and condition of the patient.

• Nurses must possess knowledge about biocultural, psychosocial, and linguistic differences in diverse populations to make accurate assessments and plan interventions.

• Although nursing has independent and dependent nursing actions, it is essential that an interdependence with all health care providers is actualized.

• Multiple quality indicators have been developed for critical care; nurses are pivotal in quality monitoring and improvement.

• AACN Practice Alerts are succinct, evidence-based directives for critical care nurses and other health care providers to ensure that the most current evidence is used to provide safe care.

• A healthy work environment is essential for establishing a collaborative, trusting, and safe environment for the delivery of patient care.