Chapter 38 Critical Care Medicine

Mechanical ventilation

1. List the typical indications for mechanical ventilation in the ICU.

2. What are some common causes of respiratory failure?

3. What are some common causes of ventilatory failure?

4. What are some indications for the need for airway protection?

5. What are some common modes of mechanical ventilation?

6. Describe the key ventilator settings in continuous mandatory ventilation (CMV) mode.

7. How can the inspiratory and expiratory time be adjusted in CMV mode?

8. What effect does a patient’s breathing effort have when mechanically ventilated in CMV mode?

9. Describe the key ventilator settings in synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) mode.

10. What effect does a patient’s breathing effort have when mechanically ventilated in SIMV mode?

11. Describe the key ventilator settings in pressure support ventilation (PSV) mode.

12. What is positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)?

13. How does PEEP improve oxygenation?

14. What are some possible adverse effects of PEEP?

15. What are some criteria that must be met before a patient can be considered ready for a trial of weaning from mechanical ventilation?

16. What is the preferred method of protocol-driven weaning from mechanical ventilation?

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation

17. What is noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV)? What are two modes of NIPPV?

18. What is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)? What are some benefits of CPAP?

19. What is bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP)?

20. What are some advantages of NIPPV?

21. What are some indications for NIPPV?

22. What are three contraindications to noninvasive mechanical ventilation?

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

23. What are the American-European Consensus Conference Definitions for acute lung injury (ALI) and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)?

24. List three direct causes and three indirect causes of acute respiratory distress.

25. What are the basic principles for the treatment and the management of mechanical ventilation of patients with ALI or ARDS?

Sedation and analgesia in the intensive care unit

26. What are some indications for patient sedation in the intensive care unit (ICU)?

27. What are the components of the Ramsay sedation scoring system?

28. What are the common side effects of the use of opioids for the sedation of critically ill patients?

29. What are the common side effects of the use of benzodiazepines for the sedation of critically ill patients?

30. What are the common side effects of the use of propofol for the sedation of critically ill patients?

31. List the common clinical findings in propofol infusion syndrome.

32. What are the advantages of ketamine as a sedative in the ICU?

33. What is the mechanism of action of dexmedetomidine? What are its hemodynamic effects?

Shock

35. List three major categories of shock. How can they be differentiated using central venous pressure (CVP) and cardiac output (CO) measurements?

36. What are some common causes of hypovolemic shock?

37. What are the common clinical findings of hypovolemic shock?

38. What is the treatment for hypovolemic shock?

39. What are the causes of cardiogenic shock?

40. What are the common clinical findings in cardiogenic shock?

41. What is the treatment for cardiogenic shock?

42. What are some common causes of vasodilatory shock?

43. What are the common clinical findings of vasodilatory shock?

44. What is the treatment for vasodilatory shock?

45. Upon which receptor subtypes does dopamine have agonist activity?

46. Upon which receptor subtypes does epinephrine have agonist activity?

47. What are the advantages of norepinephrine use in septic shock?

48. Upon which receptor does phenylephrine have agonist activity?

49. What are the hemodynamic effects of dobutamine infusion?

50. How does vasopressin differ in its mechanism of action when compared to norepinephrine?

Delirium

55. What is the incidence of delirium in the adult ICU population?

56. How is mortality impacted by the presence of delirium in the critically ill?

57. What are some common causes of delirium in a patient in the ICU?

58. What is the common method of delirium assessment in the ICU?

59. What is the treatment for delirium in a patient in the ICU?

Answers*

Mechanical ventilation

1. Mechanical ventilatory support is typically initiated for the treatment of respiratory failure due to impaired oxygenation, impaired carbon dioxide excretion (ventilatory failure), and airway protection. Patients receive mechanical ventilatory support to (1) reduce the work of breathing, (2) reverse progressive respiratory acidosis or hypoxemia, (3) reduce the risk for aspiration, or (4) ensure a patent airway with severe neck and facial swelling or trauma. (666)

2. Common causes of respiratory failure may include trauma, ARDS, sepsis, pneumonia, and cardiogenic and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. (666)

3. Ventilatory failure may be due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and/or drug intoxication. (666)

4. Airway protection indications are usually limited to conditions such as altered mental status, head and neck trauma or swelling, or significant neuromuscular disorders. (666)

5. Common modes of mechanical ventilation include continuous mandatory ventilation, synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation, pressure support ventilation, and PEEP. (666-667)

6. In CMV mode, the ventilator is programmed to deliver a set tidal volume at a set respiratory rate, thereby resulting in the delivery of a predictable minute ventilation. The ventilator will deliver its preset tidal volume at its preset time. (666)

7. To regulate the amount of time that the ventilator spends cycling in inspiration and expiration, the inspiratory flow rate is set. By increasing inspiratory flow, the set tidal volume is delivered in a shorter time, which allows more time for exhalation. (666)

8. The patient’s breathing efforts are unsupported in CMV mode. The ventilator continues to deliver its preset tidal volume at its preset time regardless of patient effort. (666)

9. In SIMV mode, the ventilator is programmed to deliver a set tidal volume and respiratory rate. In SIMV mode, however, the ventilator attempts to synchronize mandatory breaths to the patient’s own spontaneous breaths. If the patient does not initiate a breath within a set time, the ventilator delivers the set tidal volume as in CMV mode. Therefore a minimum minute ventilation is maintained in SIMV mode. (666)

10. If a patient initiates a breath during the preset time for a mandatory breath, a preset tidal volume will be delivered. Additional breaths initiated by the patient beyond those set in the SIMV mode are supported by the ventilator with an augmentation of the tidal volume by a preset pressure. It is therefore a pressure-supported breath. (666)

11. In pressure support ventilation, the ventilator does not deliver a preset tidal volume but, instead, relies on the patient’s intrinsic respiratory drive. Typically, the amount of pressure support is set between 5 and 20 cm H2O pressure to ensure adequate tidal volume and minute ventilation. In this mode, tidal volume will vary with patient effort. To use pressure support ventilation, the patient must possess an intact respiratory drive, and no residual skeletal muscle paralysis can be present. (666)

12. PEEP is positive airway pressure that is applied at the end of expiration during mechanical ventilation. The typical PEEP range is between 5 and 20 cm H2O pressure. (667)

13. PEEP functions to increase mean airway pressure and thereby minimize atelectasis. PEEP increases the functional residual capacity of the lungs and, in patients with a lung injury, results in improved pulmonary compliance. The recruitment of alveoli, or the inflation of previously collapsed alveoli, by PEEP can lead to improved oxygenation in a mechanically ventilated patient. (667)

14. Excessively high levels of PEEP can overdistend and damage alveoli. Excessive PEEP may also cause hemodynamic collapse by reducing preload to both the right and the left ventricles with a resultant fall in cardiac output. Finally, if there is inadequate time allowed for the exhalation of the delivered tidal volume, there can be a buildup of end-expiratory pressure that can lead to hemodynamic collapse. (667)

15. To consider weaning from mechanical ventilation, a patient must have recovered from the process that originally required mechanical ventilatory support, be hemodynamically stable, be able to manage their pulmonary secretions, and be able to protect their airway against the aspiration of gastric contents with an intact mental status and gag reflex. The patient should be maintaining adequate oxygen saturation with an inspired oxygen concentration of 40% or less, be able to initiate breaths, and be strong enough to generate an adequate tidal volume. The patient’s respiratory strength is usually considered sufficient for weaning if the patient is able to generate a negative inspiratory force of at least −20 cm H2O or a vital capacity of at least 10 mL/kg. In normal tidal breathing, a tidal volume of at least 5 mL/kg and a minute ventilation of no more than 10 L/min should be observed to ensure readiness for weaning from mechanical ventilation. In general, higher tidal volumes and lower respiratory rates predict success in weaning from mechanical ventilation. (667)

16. Protocol-driven weaning has been shown to reduce the length of time that patients remain on mechanical ventilatory support when compared to traditional physician weaning methods. Typically, protocol-driven weaning is managed by bedside providers (nurses and respiratory therapists) without the need for continuous physican input. In this method, patients are weaned from mechanical ventilation via a standard protocol, and when a patient meets the criteria for extubation, a physician is notified and the patient is extubated if the physician agrees. From multiple clinical trials, it has been shown that the fastest and most cost-effective weaning method is once-daily CPAP or T-piece weaning trials that are protocol driven by nurses and respiratory therapists. (667-668)

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation

17. NIPPV is the application of positive pressure to provide support of oxygenation and ventilation without an endotracheal tube. Two modes of NIPPV are (1) CPAP and (2) BiPAP. (668)

18. CPAP is constant positive airway pressure that is applied throughout both the inspiratory and expiratory phases of ventilation. CPAP improves oxygenation and ventilation by recruitment of collapsed alveoli, helps maintain a patent airway in the setting of airway obstruction such as sleep apnea, and increases mean airway pressure in patients with COPD.

19. BiPAP is similar to pressure support with PEEP ventilation because the ventilator cycles between two sets of positive-pressure settings. Positive pressure is delivered throughout the respiratory cycle, with a higher positive pressure being applied during inspiration. With BiPAP, a “backup” ventilator rate may be set. (668)

20. When compared to mechanical ventilation with an endotracheal tube, noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation has a reduced risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia, can be rapidly and easily applied with a properly fitted face mask, and can be used during short periods only, as during sleep. (668)

21. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation, or noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) is indicated in a patient who has a potentially rapidly reversible pulmonary process that requires ventilatory support. In patients with acute exacerbations of COPD, there is strong evidence that NIPPV is an effective treatment that can reduce the need for subsequent endotracheal intubation and reduce mortality. NIPPV has been used successfully to treat other forms of acute respiratory failure such as pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and postsurgical respiratory failure. NIPPV may be just as effective as conventional ventilation with respect to oxygenation and removal of carbon dioxide in these patients, and it is associated with fewer serious complications and a shorter ICU stay. (668)

22. There are specific contraindications to the use of NIPPV. The most frequently encountered problem is lack of patient compliance. Because NIPPV requires a tight-fitting mask for effective ventilation, many patients find it uncomfortable and it is poorly tolerated by those who are claustrophobic. There is also a subset of patients in whom NIPPV will not be effective in reversing their respiratory and/or ventilatory failure. It has been well-shown in the medical literature that continued use of NIPPV is harmful in this patient subset. In addition, NIPPV provides no airway protection, so it should not be used in patients with altered mental status since they may not be able to protect their own airway against aspiration. The same is also true for any patients who may have other reasons for an inability to protect their own airway, such as neuromuscular weakness or facial trauma or swelling. (668)

23. The American-European Consensus Conference defines ALI and ARDS as follows:

The lung injury must have an acute onset.

There must be bilateral infiltrates present on chest radiographs.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

24. Direct causes of acute lung injury include pneumonia, the aspiration of stomach contents, pulmonary contusion, reperfusion pulmonary edema, amniotic fluid embolus, and inhalational injury. Indirect causes of acute lung injury include sepsis, severe trauma, cardiopulmonary bypass, drug overdose, acute pancreatitis, near drowning, and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). (669, Table 41-2)

25. The treatment of ARDS generally remains supportive. The use of low tidal volume ventilation in patients with ALI or ARDS (6 mL/kg) versus the traditional standard tidal volumes (12 mL/kg) has been shown to decrease mortality. Lower tidal volumes function to “protect” the lung by preventing overdistention of remaining normal lung regions. Patients who are ventilated with lower tidal volumes tend to have lower arterial oxygen tension and higher arterial carbon dioxide tension. This is termed permissive hypercapnia and hypoxemia, in recognition of the fact that to normalize arterial blood gas, significantly more harmful mechanical ventilation may be required. (669)

Sedation and analgesia in the intensive care unit

26. Indications for patient sedation in the ICU include the provision of analgesia, anxiolysis, or amnesia and to protect the patient from removing intravenous lines, catheters, drains, or tubes. In certain circumstances sedation may be administered to prevent seizures, decrease intracranial pressure, treat for the withdrawal from substances such as ethanol, and to sedate while administering concomitant neuromuscular blocking drugs. (669)

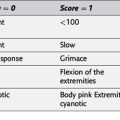

27. The RASS is a widely used tool to help quantify the level of sedation of a patient in the ICU. It is a linear scale from 1 to 6 that describes a patient’s ability to respond to stimulation while under sedation. The stimulation provided to the patient is either a verbal command or a light glabellar tap. The response to this stimulation varies from a RASS score of 1: “Anxious and agitated or restless, or both,” to a RASS score of 6: “No response to a light glabellar tap.” The RASS score of 3: “Responding to commands only” is usually considered to be the optimum sedation level. (669-670, Table 41-3)

28. Opioids may be useful for sedation in the critically ill patient when the patient has pain either as a result of surgery, from indwelling catheters, or for sedation during a painful procedure, such as chest tube placement. The most dangerous side effect of opioids is that of respiratory and central nervous system sedation that can be synergistic when combined with other sedatives, such as benzodiazipines. Other side effects of opioids when used for sedation include constipation, urinary retention, and tolerance. (670-671)

29. Due to their mechanism of action on GABA receptors, benzodiazepines have multiple side effects. These include significant CNS depression (especially when combined with opioids), accumulation of drug or active metabolites when administered over a prolonged period, and life-threatening withdrawl if removed too quickly in patients who have become tolerant of their effects. In addition, when sedation with benzodiazepines is compared to dexmedetomidine, patients receiving benzodiazepines appear to have longer duration of mechanical ventilation, as well as an increased risk of delirium. (671)

30. Despite its ease of use, propofol has many significant side effects which may limit its use in the ICU. Propofol causes hypotension by decreasing myocardial contractility and reducing systemic vascular resistance. In hemodynamically unstable patients with low cardiac output or low afterload (or both), propofol must be used with caution. Propofol is also a profound respiratory depressant. Although most patients who receive propofol in the ICU are intubated and maintained on mechanical ventilation, occasionally propofol may be used in nonintubated patients. In these patients, extreme caution must be exercised to prevent severe respiratory depression with profound respiratory acidosis. Propofol is formulated in a lecithin base and therefore has a high fat content. Patients who are receiving long-term infusions of this drug must be periodically checked for hypertriglyceridemia. There have been many case reports of patients developing severe pancreatitis after prolonged propofol administration. (671)

31. This is a rare syndrome that is associated with the prolonged use of propofol as a sedative agent in the ICU setting. Generally, propofol infusion syndrome is defined as a relatively sudden onset of metabolic acidosis with cardiac dysfunction and at least one of the following findings: rhabdomyolysis, hypertriglyceridemia, and renal failure. Some studies have also used hepatomegaly due to fatty liver infiltration and lipemia as additional criteria. The early cardiac findings include bradycardia and right bundle branch block. If propofol infusion syndrome is suspected, the propofol infusion should be discontinued immediately and another sedative agent should be chosen, as the mortality of this syndrome has been reported to be as high as 80%. (671)

32. Ketamine has proved to be useful in the ICU because of its ability to produce profound analgesia without significant respiratory depression. This makes ketamine an excellent choice for patients with chronic pain who may require excessively large doses of opioids for pain relief, or in patients who are already on large doses of narcotics and in whom a further increase of narcotics will have minimal effects due to tolerance. Ketamine is also useful for patients who need to undergo brief, painful procedures in the ICU. Ketamine also has intrinsic sympathomimetic properties that increase systemic blood pressure and heart rate during its infusion. This may be useful when sedation and analgesia are required for a hemodynamically unstable patient. Ketamine is often combined with propofol in such patients to counteract the reduced blood pressure associated with propofol while providing adjuvant analgesia. Ketamine may not be useful in neurosurgical patients because it increases intracranial pressure, increases cerebral metabolic oxygen requirements, and decreases the seizure threshold. (671-672)

33. Dexmedetomidine acts by binding to α2 receptors both centrally and peripherally. Central α2-binding at presynaptic neurons inhibits the release of norepinephrine. The central effects of these drugs produce analgesia, sedation, anxiolysis, and hypotension. At the level of the spinal cord, α2-activation is thought to modulate pain pathways, and this is the probable site of action for the analgesic effects of this drug. With increasing doses, dexmedetomidine begins to bind peripheral α1 and α2 receptors, inducing vasoconstriction and hypertension at very high doses. Overall, in the recommended dosage range, the effect is to decrease systemic blood pressure by means of a decrease in both systemic vascular resistance and heart rate. (672)

Shock

34. Shock is a clinical condition in which there is inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygenation to end organs such as the brain, heart, liver, kidneys, and abdominal viscera. Early in its course, shock may be reversible, but ongoing shock results in multiorgan system failure and ultimately death. (673)

35. The major categories of shock include hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and septic (or other forms of vasodilatory shock). In hypovolemic shock, both CO and CVP are reduced due to decreased venous return. In contrast, cardiogenic shock is typified by a decrease in CO due to poor pump function, but CVP is usually increased. Finally, in septic shock, CVP is usually decreased due to profound vasodilation and pooling of blood in the splanchnic beds, but CO is typically increased in early sepsis. However, CO may be normal or even depressed in later more advanced septic shock. (673, Table 41-5)

36. The most common cause of hypovolemic shock is major blood loss, as can occur in trauma, surgery, or with massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. (673)

37. Hypovolemic shock is caused by inadequate circulating blood volume, and therefore decreased preload and cardiac output. There is usually a baroreceptor-mediated reflex tachycardia and an increase in systemic vascular resistance. Gluconeogenesis is induced, as is sodium reabsorption from the kidneys. In addition to being hypotensive, the patient may appear cool, clammy, and pale with increased plasma glucose levels and decreased urine output. (673)

38. The treatment for hypovolemic shock requires adequate intravenous access and aggressive fluid therapy to restore circulating blood volume. Fluid resuscitation can be guided by the use of a central venous monitor or arterial blood pressure variation, as well as laboratory analysis of metabolic variables. Vasopressor therapy can be used to increase systemic blood pressure, but is generally not effective until circulating blood volume is restored. (673-674)

39. Cardiogenic shock occurs when the heart is not able to pump an adequate cardiac output. The most common cause of cardiogenic shock is myocardial infarction. Other causes include severe myocarditis, endocarditis, or a tear or rupture of a portion of the heart. (674)

40. If the right ventricle is the initial site of failure, the increased right-sided preload will be noted as increased CVP, detected clinically as distended neck veins, peripheral edema, or hepatic congestion. If the left ventricle fails, the increased preload can be detected as increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, which causes cardiogenic pulmonary edema and rales on physical examination. In either scenario, cardiac output is low, and systemic blood pressure is therefore reduced. On physical examination, a patient in cardiogenic shock appears cool and pale secondary to the high systemic vascular resistance and shunting of blood away from the skin and skeletal muscle beds. (674)

41. The goal for treatment of cardiogenic shock is to improve cardiac output and decrease afterload to reduce myocardial demand. Resuscitation should be guided by the use of central venous monitors, direct arterial blood pressure measurements, and echocardiography. Vasodilator therapy can be used to reduce preload and afterload. Dobutamine therapy may also be useful. Treatment with diuretics must be done with extreme caution. In cardiogenic shock refractory to treatment an intraaortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) or ventricular assist device (VAD) may be indicated. (674)

42. The most common cause of vasodilatory shock is sepsis. Other causes of vasodilatory shock include anaphylaxis, stroke, and spinal shock as from a high spinal cord injury. Vasodilatory shock is also the final common pathway for late-shock stages of cardiogenic and hypovolemic shock. (674)

43. In the initial stages of vasodilatory shock an increase in cardiac output may compensate for the decrease in systemic vascular resistance and the patient may appear warm and vasodilated. With worsening metabolic acidosis myocardial perfusion becomes impaired, and the patient will become increasingly cool and clammy. (674)

44. The treatment for vasodilatory shock involves adequate fluid volume resuscitation in conjunction with possible vasopressor therapy. The underlying cause of the disorder should also be treated. In septic shock early identification of the source of the infection and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics is necessary. (674-675)

45. Dopamine has both direct and indirect agonist activity at the dopamine1 (DA1), β1, and α1 receptors. Its pharmacologic action varies with dose and within individuals. At low doses (0 to 5 μg/kg/min), dopamine has predominantly DA1 receptor agonist activity. This causes dilation of the renal arterioles and promotes diuresis. At moderate doses (5 to 10 μg/kg/min), the β-effects of dopamine begin to dominate. These β1-effects cause an increase in myocardial contractility, heart rate, and cardiac output. At high doses (10 to 20 μg/kg/min), the α1-agonist effects predominate and dopamine acts to increase vascular smooth muscle tone, which increases systemic vascular resistance. This causes a decrease in splanchnic and renal blood flow similar to the effects of high-dose phenylephrine. (675)

46. Epinephrine causes direct stimulation of α1, β1, and β2 receptors. At lower doses, epinephrine acts primarily as a β receptor agonist, whereas at higher doses, it has increasing α1 receptor effects. Increases in heart rate, myocardial activity, and cardiac output reflect β1 receptor effects. The principal β2-effects are bronchial and vascular smooth muscle relaxation. At higher doses, the α1-effects of epinephrine act to increase systemic vascular resistance and reduce splanchnic and renal blood flow while maintaining both cerebral and myocardial perfusion pressure. (675-676)

47. Norepinephrine is a direct-acting adrenergic agonist with activity at both the α1 and β1 receptors. As a result, norepinephrine increases blood pressure through its α1-effects on increasing systemic vascular resistance. The β1-effects of norepinephrine also contribute to increased myocardial contractility and cardiac output. There has been renewed interest in norepinephrine specifically for the treatment of septic shock. It is thought that this β1-activity may help offset the myocardial dysfunction associated with severe sepsis and septic shock. Both preclinical and limited clinical data suggest that norepinephrine is the pressor of choice for patients in septic shock. (676)

48. Phenylephrine is a direct-acting, highly selective α1 receptor agonist which increases systemic vascular resistance and arterial blood pressure. Phenylephrine can cause a reflex bradycardia, which can decrease cardiac output. Phenylephrine can be used to increase systemic vascular resistance in shock, but in high doses higher than 200 μg/min it has little additional therapeutic effect and may cause splanchnic ischemia. (676)

49. Dobutamine is a mixed β1 and β2 receptor agonist. As a result, the primary effect of dobutamine is to increase both heart rate and myocardial contractility. Dobutamine also relaxes vascular smooth muscle via binding at β2 receptors. This combination acts to increase cardiac output by improving ventricular function (β1-effect) and decreasing systemic vascular resistance (β2-effect). Because of its β2-effects, some patients may become hypotensive, particularly those with decreased intravascular volume. (676)

50. Vasopressin is a potent vasoconstrictor that does not work via the adrenergic receptor system as do most other vasopressors and inotropes. Rather, vasopressin binds to peripheral vasopressin receptors to induce potent vasoconstriction via phosphodiesterase inhibition. In contrast to norepinephrine, vasopressin has no intrinsic inotropic effects. However, vasopressin remains efficacious as a vasoconstrictor even in the setting of severe acidosis. As such vasopressin may provide a useful alternative to catecholamines, which do not function well in the setting of profound acidemia. (676)

Acute renal failure

51. The definition of ARF varies, but it is often described as an abrupt decrease in renal function, which is defined as urine output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hr or a 50% increase in serum creatinine over a 24-hour period. (676-677)

52. Acute renal failure is normally categorized as prerenal (inadequate renal perfusion pressure), intrarenal (vascular, glomerular, or interstitial dysfunction), or postrenal (usually obstructive). In the management of ARF, it is essential to recognize and treat prerenal failure by ensuring adequate fluid resuscitation and systemic blood pressure, as well as to identify any postrenal obstruction through the use of ultrasound or other imaging techniques. If the ARF has been determined to be intrarenal, it most likely represents acute tubular necrosis. In addition to the history, which may include exposure to nephrotoxic drugs or prolonged hypotension, examination of urinary sediment may show renal tubular epithelial cells or granular casts. (676-677)

53. Indications for acute hemodialysis include excessive intravascular fluid volume, hyperkalemia, acidemia, uremia, toxins, or other electrolyte abnormalities. (677)

Delirium

54. Delirium is defined by the DSM-IV as a disturbance of consciousness with reduced ability to focus or sustain attention that is associated with a change in cognition or perceptual disturbances that are not accounted for by a preexisting dementia. (677)

55. Delirium is widespread in the adult ICU population with estimates of an incidence between 48% and 87%, depending on the acutal population studied. Because there are two forms of delirium, the hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes, the diagnosis is difficult to make and the actual incidence of delirium is frequently underestimated. Hyperactive delirium is usually quite obvious when present, because patients are typically combative and have profound altered mental status. Hypoactive delirium on the other hand is much more incidious, since patients are typically quiet and may appear calm and content on casual examination. (677)

56. Delirium is not a benign condition. Numerous studies have shown an increased risk of mortality among ICU patients who develop delirium. These risks vary from a greater than threefold increase in 6-month mortality to a 10% increase in the risk of death for every day spent in a state of delirium in the ICU. Delirium is associated with an increased number of days a patient will spend mechanically ventilated, as well as increased days in the ICU and hospital. In addition, delirium is associated with an increased risk of developing dementia in later life. It is unclear whether delirium may actually cause dementia, or if patients who are at greatest risk of dementia or have an early subclinical form of dementia are more likely to have episodes of delirium in the ICU. (677)

57. The causes and conditions assciated with delirium in the ICU setting are numerous. They include preexisting cognitive impairment, advanced age, increasing severity of illness, multiorgan dysfunction, sepsis, immobilization, sleep deprivation, pain, mechanical ventilation, and the use of psychoactive drugs, particularly benzodiazepines. (677)

58. To actively treat delirium, it must be diagnosed first. The most widely used method of monitoring for delirium is the CAM-ICU assessment for delirium. CAM stands for confusion assessment method, and this tool should be used daily to assess for delirium in all ICU patients except those who are deeply sedated or comatose. (677)

59. Delirium in a patient in the ICU setting should be treated by first searching for an underlying cause and correcting the cause. Attempts should be made to actively orient the patient to their surroundings. If delirium still occurs, haloperidol may be helpful in improving orderly thought processes. (677)

Nutritional support

60. Providing optimal nutrition to patients in the ICU is important for wound healing, to maintain skeletal muscle mass and strength, and for the prevention of infection. Optimal nutrition may facilitate weaning from mechanical ventilation and rehabilitation. (677)

61. Patients may be fed either enterally (usually by a nasojejunal feeding tube) or parenterally (intravenously). If possible, it is always preferable to feed enterally. Advantages of enteral feeding include decreased cost, ease of administration, maintenance of normal gastrointestinal physiology, and less risk for infection. Parenteral nutrition formulas are easily infected, which greatly increases the risk for catheter-related blood stream infections. Additionally, without enteral feeding, the normal gastrointestinal tract begins to atrophy. Such atrophy causes loss of mucosal thickness, alteration of pH, and loss of gastrointestinal tract–associated lymphoid tissue. These changes can result in replacement of normal gastrointestinal tract flora with more pathologic organisms and increased translocation of these organisms across the increasingly atrophic gastrointestinal tissue, leading to an increased risk of sepsis. Parenteral nutrition is usually reserved for those patients in whom enteral feeding is not possible. This includes patients with bowel obstruction or ischemia, short gut syndrome, or other malabsorption problems. (678)

Rapid response teams

62. Rapid response teams frequently use ICU professionals, including physician intensivists, critical care nurse practitioners, ICU nurses, and respiratory therapists. These teams form a multidisciplinary group to evaluate and treat patients early in the course of a physiologic decline, and make interventions which will hopefully avert an impending cardiopulmonary arrest. (678)

Intensive insulin therapy

63. Recently, there has been considerable controversy regarding the optimum method of blood glucose control in critically ill patients. Initially, it was thought that intensive insulin therapy to achieve a blood glucose level between 80 to 100 mg/dL would improve survival in ICU patients. This notion has been questioned, and recent studies have shown that intensive insulin therapy to keep very tight glucose control does not improve survival, but increases the risks of significant hypoglycemia and actually increases mortality. This is in part due to increased episodes of hypoglycemia associated with strict control. Currently, the best level at which blood glucose should be maintained in critically ill patients has not been elucidated, but the evidence would support maintaining a blood glucose level in a moderate range between 140 to 180 mg/dL. This level minimizes the risks of severe hypoglycemia (less than 40 mg/dL) and hyperglycemia (greater than 200 mg/dL). (678)

End-of-life issues

64. The physician intensivist should not regard death as a failure, but rather as a normal course of life. Indeed, the physician may be called upon for his or her professional opinion when the family is making its decision. Once a family has elected to stop treatment of a critically ill patient, the physician should attempt to make the passing of life as dignified as possible. Mechanical ventilatory support can be terminated and either T-piece ventilation or extubation of the trachea should take place. Vasopressor therapy and hemodialysis may be discontinued. In addition, patients should be given adequate sedation for the relief of discomfort, but not to “hasten” death. (678-679)