Creating patient flow

This book is dedicated to the improvement of individuals’ clinical and professional skills in emergency care. For some time now all the authors have been studying and working in wide-scale health system reforms and this work has exposed us to a wealth of knowledge that has enabled us to reconsider how we best serve communities of health need (Dolan & Hawes 2009, Ardagh et al. 2011). We realize now that in healthcare we have a responsibility as health practitioners beyond the patient in front of us right now; we have a responsibility to the patient in the waiting room, arriving in the ambulance, and to the patient who may not know they will shortly be on their way to the Emergency Department (ED). In other words, ensuring we are ready to handle the next patient that comes through the door in the same way we manage the patient in front of us right now, no matter how busy it gets.

Health system environments

Health systems have not evolved significantly in the way they are organized in the last 100 years. New technology, bigger, brighter and more welcoming buildings and new clinical techniques mask what essentially is an industry that has kept its Victorian design into a new millennium. Just like craftsman-type industries prior to the 20th century industrial revolution in manufacturing techniques, health is a collection of inter-related cottage industries (Swensen et al. 2010). Every clinical service can be compared to a craft-based business of old, where highly specialized individuals within a particular clinical specialty deliver specialist knowledge and techniques. A hospital is often like a large mall full of specialist businesses to which a patient is sent for expert assessment. As a result the patient gets passed from service to service, from cottage industry to cottage industry, during the course of their care and treatment.

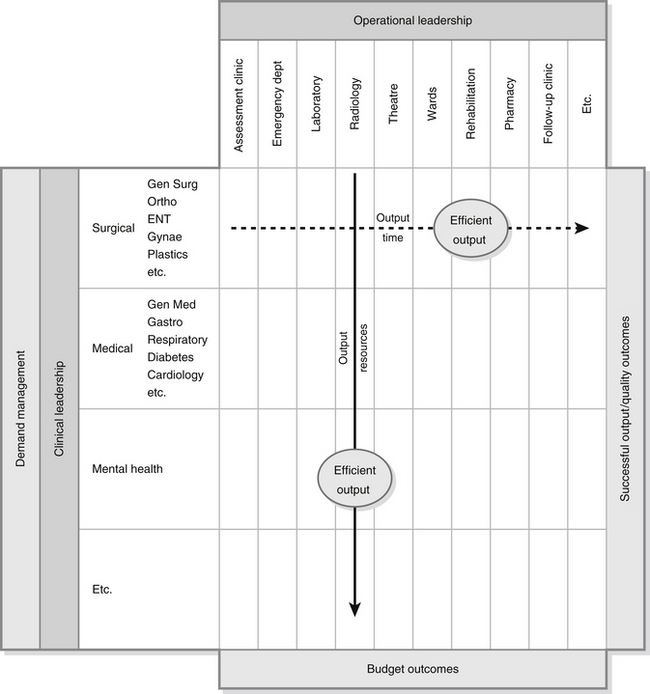

The organization and leadership of hospital resources further exposes this sense of passing the patient from one process area to another. Figure 42.1 highlights how a hospital setting is a matrix of services attempting to get patient outcomes via a series of functional business areas that are vertical silos. Traditionally, the management model of hospital systems has focused on managing the functional business units, or the vertical slices of the patient journey, often as discrete businesses. Each functional business unit is charged with being as efficient as possible with the resources they are given, where the resources are usually monetary based. In this way each independent business is seeking to maximize the use of its resources to achieve either more revenue, reduce costs or higher utilization of resources. These functional business units serve many different clinical specialities whose needs can be very different and competing; therefore, by default, they create their own rules and business practices that may not align with the other functional business units.

Figure 42.1 Matrix of healthcare.

Patient time

Health systems operate as complex supply chains where the goal is to achieve timely and appropriate outcomes for the population’s needs. Where manufacturing systems are moving inventory and parts around the world to wholesalers and assembly plants; health systems are managing time – patients’ time. Where Toyota is concerned about limiting its inventory to the next few hours of production as a way to reduce the time from paying suppliers to being paid by product buyers (Womack & Jones 1996), the health system has a focus on reducing the time a patient spends in the health system from the start of a health issue to the time the issue is resolved. In many respects, patient time is the health system equivalent of inventory.

How Lean Thinking principles value time

Over 40 years, Toyota Motor Company has developed the Toyota Production System using techniques that are known more widely as Lean Thinking (Womack & Jones 1996, Stone 2012). Lean Thinking is a culture focused on delivering the most value with the least waste, for the end consumer (Liker & Convis 2011, Kaplan 2012). It has been designed to support complex supply chains, focusing on:

• ‘just-in-time’ (JIT) delivery of products thus minimizing storage space

• error-proofing processes, thereby minimizing waste and delays due to poor parts

• continuously eliminating excessive product movement/handling to create the fewest steps, therefore lessening the chance of errors (Westwood et al. 2007).

In patient terms, the longer patients wait, the more staff effort is involved, bigger waiting rooms are required, poorer quality of care can result. There is a direct correlation between waiting times in EDs and increased morbidity and mortality (Ardagh & Richardson 2004, Richardson 2006, Sprivulis et al. 2006, Richardson & Mountain 2009, Johnson et al. 2012, Mahler et al. 2012). Industry has much more to teach healthcare than we sometimes imagine, as it has addressed metaphorically similar issues many years ago. To achieve this focus Toyota recognized the contribution of staff, and in particular they recognized and valued frontline staff as long-term partners that learn, adapt and empower improvements. Managers and leaders in Toyota are driven to value frontline staff and their time; with particular emphasis on removing barriers to staff creating more value. Having staff spend time on producing a part that is not needed now, it may be needed but not now, is seen as disrespectful of the staff’s time; the work has added no value (Liker & Franz 2011). Having staff skills and capabilities under-utilized is also considered disrespectful of staff time, i.e., the time they have invested in developing these skills.

Lean Thinking during the first decade of the new millennium has been adopted widely by health systems and is increasingly recognized for its potential to transform individual business processes (Baker & Taylor 2009, Millard 2011, Stone 2012). The true value and opportunity is where the tools of Lean Thinking are applied across the health system, across the patient’s journey, where the patient is a substitute for inventory in a manufacturing environment, which must be moved through the health system in a timely manner. It is important to stress that in viewing the patient as metaphorical inventory is not about being disrespectful, rather the opposite, it is underlining that principles that apply in industry can readily be applied in healthcare. A true Lean Manufacturing culture seeks to have inventory valued in the same way we value people, with respect.

The concept of patient time being important in health systems and the reasons why it is so important can be hard to understand as it can be counter-intuitive to logic and professional training. The process for managing patients has its roots in Napoleonic warfare and is now pervasive in all clinical practice. The use of triaging and prioritization scores is viewed as a normal and necessary practice for determining who needs help now and who can wait, and who will never be seen (Allen & Jesus 2012). In war, where demand can rapidly outstrip supply of clinical resources, the use of battlefield triage makes sense; but why does this methodology continue in everyday practice? The underlying assumption of triage is there are not enough resources to treat everyone that seeks our help (see Chapter 35).

However, is this really true for normal population clinical needs? Most health systems are adept at treating the demand on the system; it’s just a matter of when they are treated. With the exception of emergency care where critical care demand may impact on resources, most of healthcare demand is stable and predictable. The biggest variable is created by us, the health professionals. By prioritizing demand (triaging), patients are placed into queues based on urgency of need. Every time someone with a higher need enters the system, someone of a lower need is asked to wait longer. This reprioritization may not be transparent to the majority of patients and staff as it happens on waiting lists, where the patient is waiting at home; but what about the patient that comes to the ED who may be categorized as triage 3 and ultimately is assessed as needing surgery? Every time a patient with a higher need comes into the system this patient will be asked to wait longer. In extreme examples, these patients may have been ‘nil by mouth’ for three to four days, sitting in a hospital bed waiting for access to a treatment room or operating theatre. The patient’s condition may have deteriorated and they pick up a hospital-borne infection. This patient initially needed a fifteen-minute surgical procedure, and would have gone home the same day. Instead they spent a week in hospital using up resources that could have been applied in other ways, as well as suffering needless pain, harm and distress. In patients with fractured neck of femur, the correlation between non-medical delays in surgery and increased morbidity and mortality is now well established (Bottle & Aylin 2006, Kalson et al. 2009).

EDs that use ‘streaming’, for example, split their capacity and resources into two separate patient streams, minors and majors, are focused on applying a key principle of Lean Thinking, First In First Out (FIFO). By streaming patients based on need, it is possible to prioritize patients based on time of arrival rather than just need. In this way patients with relatively minor conditions are processed faster (high turnover) with a focus on creating flow. This is also the theoretical basis of See and Treat (NHS Modernisation Agency 2004, King et al. 2006, Hoskins 2010).

Creating goals of patient flow

Average length of stay in hospitals is an important measure of ward capacity performance as the higher the number of days, or indeed hours, a patient spends in the system the more direct resources they consume, such as beds/chairs, rooms, food, laundry, etc. The more time people spend in hospital, the bigger the hospital space and staffing resources required to store and manage patients and their visitors; therefore, the more patient time in the system, the more resources we need to have, either directly managing patient treatment or indirectly managing the patient journey, such as waitlist, etc. The other risk for patients is that the more time they spend in hospital than is essential, the greater their risk of picking up healthcare-acquired infections (HCAI), which not only adds to their length of stay, but more importantly, adds needless harm and suffering. In Europe, HCAIs cause 16 million extra bed days and 37 000 attributable deaths and contribute to an additional 110 000 deaths every year (World Health Organization 2010).

Does your environment have clear goals? Are these goals based on patient time or quality of outcome; and do they encourage continuous improvement? Without these clear goals how do we know if we are making a difference. Beyond gut feeling, how do we know if we have had a good shift today or a difficult one? While EDs in most countries now have goals or more commonly ‘targets’, usually four or six hours from ED arrival to discharge or admission/transfer, staff frequently feel they are imposed. They remain an ED and not an organizational health system target, and in reality it’s the nurses who make it happen. Even when the target is reached, too often it is with more a sense of relief than achievement. This is not what Lean Thinking and patient flow is about, which is to create sustainable and in many ways self-sustaining systems that continue to focus on improvement not plateauing and ultimately reversing earlier success. Lean Thinking is not about the tools, it’s about the thinking that underpins it, and a relentless focus on eliminating everything that does not add value to the patient’s experience and safety of care.

Identifying waste in the health system

As indicated above, waste is a significant problem in healthcare and indeed all service and manufacturing industries. As little as 10 % of all activities provide value, which may be defined as adding ‘value’ to the customer, be they a patient or member of staff (Baker & Taylor 2009). Box 42.1 defines and provides numerous examples of waste using the mnemonic TIMWOODS and underlines that, perhaps counter intuitively, the greatest challenge in healthcare is not necessarily the lack of resources, but the enormous levels of waste that exist.

Each stage of the 5S process is specifically designed to transform the workplace and set in motion a culture of waste elimination (Hodge & Prenovost 2011). Box 42.2 defines and describes 5S.

Understanding variation in demand

Silvester, Steyn and colleagues have studied the impact of variation on health services, and published a series of articles on the art of understanding and managing variation in the health system (Silverster et al. 2004, Walley et al. 2006, Allder et al. 2011). Their work is based, among other things, on Queuing Theory first developed by Agner Erlang, a Danish engineer in 1909 who worked for the Copenhagen Telephone Exchange to help the telecommunication industry to assign sufficient switchboard capacity to meet the majority of demand (Erlang 1909). Too much capacity would mean money wasted, too little capacity and calls would not connect. Queuing theory is the mathematical study of waiting lines or queues and is widely used in telecommunication, traffic engineering, computing, manufacturing and service industries and health.

The two key messages of this work are: reduce the causes of variation in demand and capacity; and then set capacity to 70–85 % of the variation in demand (see Box 42.3). It is important to note that understanding when to use 70 % versus 85 % is based on how much variation occurs in demand, and is outside the intent of this chapter.

Pulling all the flow elements together

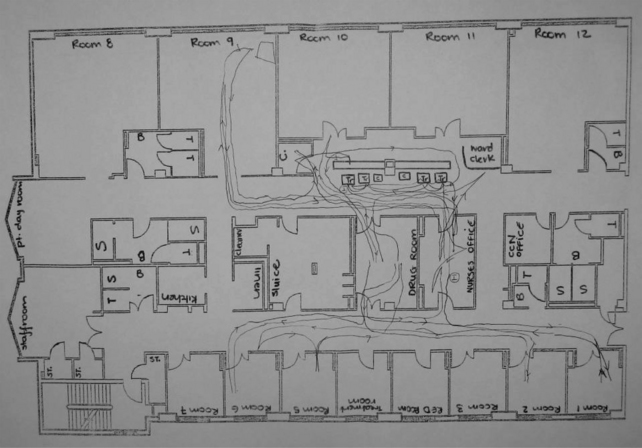

When clinicians lead service improvements, supported by managers, the level of change can be significant and, as important, sustained. One of the authors (Ardagh) co-led a major reform of emergency department’s processes, plant and people. The case study of Project RED (Rejuvenating ED) can be found in Box 42.4.

Conclusion

This chapter has outlined three key concepts:

1. Identify the goal: What is the service goal in your department? Is it related to time? And does it challenge us?

2. Understand value: what parts of the patient journey are value adding? Can we eliminate the non-value components to a patient’s journey, such as the waits and delays or repeated steps? What staff work is necessary and what can be reassigned? Should a staff member be expected to do certain work, have they been trained sufficiently and will it benefit the patient outcome? Understanding value can be challenging as we need to analyse what we do and impartially assess is this necessary or is it waste. Identify the seven wastes in the patient’s journey and in your work. Seek to eliminate as many wastes as possible.

3. Create flow: the ultimate goal is to create health outcomes at the rate the community needs them. Removing batches of patients from the system reduces variation and reduces the time to treatment and discharge. Any demand system will have natural variation, but most variation is created by us through poor understanding of demand and capacity, and poor process. Variation is the cause of most queues in health, and as such is the most misunderstood driver of health outcomes.

These are starting points to understanding how service design can best be improved. On their own they are not sufficient to achieving high performance; but should act as the guiding principles of any redesign of service.

A key concept of any redesign is to involve the whole health system in the design and improvement process; especially on creating flow. To improve ED service delivery requires a combination of partners from across the health system to ensure that the true system constraints are identified and fixed, which may involve the role of ED changing or the management of patient conditions changing (Holden 2011). Focusing the principles of this chapter on departments in isolation to the health system or patient journey across the health system, will limit the success and benefits of Lean methods.

Any process needs to understand demand and workload, and should seek to create standard workflow, or a common understanding of how work is done. Predicting demand has been well proven to work within health (Martin et al. 2010); translating this demand into capacity consumption or workload is a subject beyond the focus of this book. It is, however, a key consideration in designing patient flow, as the goal is to predict demand on the ED by shift and to translate this demand into resources such as beds, doctors, nursing, allied health, etc.

References

Allder, S., Walley, P., Silvester, K. Is follow-up capacity the current NHS bottleneck. Clinical Medicine. 2011;11(1):31–34.

Allen, M.B., Jesus, J. Disaster Triage. In: Rosen P., Adams J., Derse A.R., Grossman S.A., Wolfe R., eds. Ethical Problems in Emergency Medicine: A Discussion-based Review. New York: J Wiley & Sons, 2012.

Ardagh, M., Richardson, S. Emergency department overcrowding. Can we fix it? The New Zealand Medical Journal. 2004;117(1189):774–779.

Ardagh, M., Pitchford, A., Esson, A., et al. Project RED – a succesful methodolgoy for improving emergency department performance. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 2011;124(1344):54–63.

Baker, M., Taylor, I. Making Hospitals Work: How to Improve Patient Care While Improving Saving Everyone’s Time and Hospitals’ Resources. Ross-on-Wye: Herefordshire, Lean Enterprise Institute; 2009.

Bottle, A., Aylin, P. Mortality associated with delay in operation after hip fracture: observational study. British Medical Journal. 2006;332:947–951.

Dolan, B., Hawes, S. Lean Thinking & Leadership, third ed. Sydney: NSW Health; 2009.

Erlang, A.K. The Theory of Probabilities and Telephone Conversations. Nyt Tidsskrift for Matematik B. vol. 20, 1909.

Hodge, C., Prenevost, D. 5S and demand flow: Making room for continuous improvement. In: Wellman J., Hagan P., Jeffries H., eds. Leading the Lean Healthcare Journey: Driving culture Change to Increase Value. New York: Productivity Press, 2011.

Holden, R.J. Lean thinking in emergency departments: a critical review. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2011;57(3):265–278.

Hoskins, R. Is it time to ‘Lean’ in emergency care? International Emergency Nursing. 2010;18(2):57–58.

Johnson, E.J., Smith, A.L., Mastro, K.A. From Toyota to the bedside: Nurses can lead the lean way in health care reform. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2012;36(3):234–242.

Kalson, N.S., Mulgrew, E., Cook, G., et al. Does the number of trauma lists provided affect care and outcome of patients with fractured neck of femur? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 2009;91(4):292–295.

Kaplan, G. Waste not: The management imperative for healthcare. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2012;57(3):160–166.

King, D.L., Ben-Tovim, B.I., Bassham, J. Redesigning emergency department patient flows: application of lean thinking to health care. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2006;18:391–397.

Liker, J., Convis, G.L. The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership: Achieving and Sustaining Excellence Through Leadership Development. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Liker, J., Franz, J.K. The Toyota Way to Continuous Improvement: Linking Strategic Excellence to Achieve Superior Performance. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Mahler, S.A., McCartney, J.R., Swoboda, T.K., et al. The impact of emergency department overcrowding on resident education. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;42(1):69–73.

Martin, M., Champion, R., Kinsmand, L. Mapping patient flow in a regional Australian emergency department: A model driven approach. International Emergency Nursing. 2010;19(2):75–85.

Millard, W.B. If Toyota ran ED: What lean management can and cannot do. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2011;57(6):13A–17A.

NHS Modernisation Agency. See and Treat. London: Modernisation Agency; 2004.

Richardson, D.B. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184(5):213–216.

Richardson, D.B., Mountain, D. Myths v facts in emergency department overcrowding and access block. Medical Journal of Australia. 2009;190(7):369–374.

Silvester, K., Lendon, R., Bevan, H., et al. Reducing waiting times in the NHS: is lack of capacity the problem? Clinician in Management. 2004;12(3):105–109.

Sprivulis, P.C., Da Silva, J.A., Jacobs, I.G., et al. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184(5):208–212.

Stone, K.B. Four decades of lean: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma. 2012;3(2):112–132.

Swensen, S.J., Meyer, G.S., Nelson, E.C., et al. Cottage industry to postindustrial care – the revolution in health care delivery. The New England Journal of Medicine. 362(5), 2010. [e12(1)–e12(4)].

Walley, P., Silvester, K., Steyn, R. Managing variation in demand: Lessons from the UK National Health Service. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2006;51(5):309–322.

Westwood, N., James-Moore, N., Cooke, M. Going Lean in the NHS. Warwick: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2007.

Womack, J.P., Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking: Banish waste and Create Wealth in your Organization. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1996.

World Health Organization. The Burden of Healthcare Acquired Infections: A Summary. Geneva: WHO; 2010.